Full Text (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Albion Full Cast Announced

Press release: Thursday 2 January The Almeida Theatre announces the full cast for its revival of Mike Bartlett’s Albion, directed by Rupert Goold, following the play’s acclaimed run in 2017. ALBION by Mike Bartlett Direction: Rupert Goold; Design: Miriam Buether; Light: Neil Austin Sound: Gregory Clarke; Movement Director: Rebecca Frecknall Monday 3 February – Saturday 29 February 2020 Press night: Wednesday 5 February 7pm ★★★★★ “The play that Britain needs right now” The Telegraph This is our little piece of the world, and we’re allowed to do with it, exactly as we like. Yes? In the ruins of a garden in rural England. In a house which was once a home. A woman searches for seeds of hope. Following a sell-out run in 2017, Albion returns to the Almeida for four weeks only. Joining the previously announced Victoria Hamilton (awarded Best Actress at 2018 Critics’ Circle Awards for this role) and reprising their roles are Nigel Betts, Edyta Budnik, Wil Coban, Margot Leicester, Nicholas Rowe and Helen Schlesinger. They will be joined by Angel Coulby, Daisy Edgar-Jones, Dónal Finn and Geoffrey Freshwater. Mike Bartlett’s plays for the Almeida include his adaptation of Maxim Gorky’s Vassa, Game and the multi-award winning King Charles III (Olivier Award for Best New Play) which premiered at the Almeida before West End and Broadway transfers, a UK and international tour. His television adaptation of the play was broadcast on BBC Two in 2017. Other plays include Snowflake (Old Fire Station and Kiln Theatre); Wild; An Intervention; Bull (won the Olivier Award for Outstanding Achievement in an Affiliate Theatre); an adaptation of Medea; Chariots of Fire; 13; Decade (co-writer); Earthquakes in London; Love, Love, Love; Cock (Olivier Award for Outstanding Achievement in an Affiliate Theatre); Contractions and My Child Artefacts. -

In the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708

international journal of military history and historiography 39 (2019) 7-33 IJMH brill.com/ijmh Britain, Austria, and the “Burden of War” in the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708 Caleb Karges* Concordia University Irvine, California [email protected] Abstract The Austrian and British alliance in the Western Mediterranean from 1703 to 1708 is used as a case study in the problem of getting allies to cooperate at the strategic and operational levels of war. Differing grand strategies can lead to disagreements about strategic priorities and the value of possible operations. However, poor personal rela- tions can do more to wreck an alliance than differing opinions over strategy. While good personal relations can keep an alliance operating smoothly, it is often military necessity (and the threat of grand strategic failure) that forces important compro- mises. In the case of the Western Mediterranean, it was the urgent situation created by the Allied defeat at Almanza that forced the British and Austrians to create a work- able solution. Keywords War of the Spanish Succession – Coalition Warfare – Austria – Great Britain – Mediter- ranean – Spain – Strategy * Caleb Karges obtained his MLitt and PhD in Modern History from the University of St An- drews, United Kingdom in 2010 and 2015, respectively. His PhD thesis on the Anglo-Austrian alliance during the War of the Spanish Succession received the International Commission of Military History’s “André Corvisier Prize” in 2017. He is currently an Assistant Professor of History at Concordia University Irvine in Irvine, California, usa. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2019 | doi:10.1163/24683302-03901002Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 03:43:06AM via free access <UN> 8 Karges 1 Introduction1 There were few wars in European history before 1789 as large as the War of the Spanish Succession. -

Apocryphilia

Apocryphilia Simon Matthews Our Island Story Before the teaching of history to children in this country descended to its current formula of dinosaurs + Romans + Henry VIII + Hitler (with a side helping of slavery) the past was taught in a rather different way. Many who were at primary school pre-1980 will be familiar with it: Our Island Story, the carefully nuanced account of how ‘the British Isles’ produced the greatest and most progressive people in the world. Written in 1905 it was, remarkably (or not?), still a common textbook 70 years later. It’s durability, popularity and influence, over a century later, has been recently cited by prime minister David Cameron and the centre-right think tank Civitas as an example of something they would like to see updated and reintroduced. Why is this? The Our Island Story narrative certainly has its attractions. Stressing national unity, in which Englishness is overwhelmingly predominant, it gives key early roles to Alfred the Great and William the Conqueror – the latter not, of course, English – with the repelling of foreign invasions and conquests (nothing since 1066) a critical factor, highlighted by the dispersal of the Spanish Armada in 1588 and, latterly, the defeat of Napoleon (1815) and Hitler (1940). British/English excursions into Europe are seen as the brilliantly executed ventures of plucky underdogs (Agincourt, Waterloo and Dunkirk are typical here) against overwhelming odds. The literary backdrop, from Shakespeare, Milton, Pepys, Dickens etc., embellishes this. Milton appears more or less in tandem with Cromwell, both as exemplars of grimly moral, upstanding and typically English parliamentarians – refusing to bow down before Rome and ensuring the lasting legitimacy of the House of Commons.....this being portrayed throughout the book as the finest and fairest legislature in the world. -

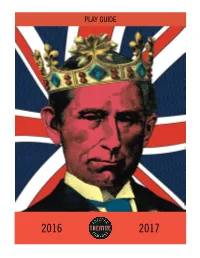

KC3 Play Guide R1 Compr

PLAY GUIDE 2016 2017 About ATC .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction to the Play ............................................................................................................................. 2 Meet the Playwright ................................................................................................................................... 2 Meet the Characters .................................................................................................................................. 3 The Real Royals ......................................................................................................................................... 5 The Line of Succession .......................................... ................................................................................... 12 British Parliament and Positions .............................................................................................................. 13 British Politics ........................................................................................................................................... 16 Royal Rituals ............................................................................................................................................. 18 King Charles and the Bard ....................................................................................................................... -

The Colonial Book and the Writing of American History, 1790-1855

HISTORY’S IMPRINT: THE COLONIAL BOOK AND THE WRITING OF AMERICAN HISTORY, 1790-1855 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lindsay E.M. DiCuirci, M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Elizabeth Hewitt, Adviser Jared Gardner Susan Williams Copyright by Lindsay Erin Marks DiCuirci 2010 ABSTRACT “History’s Imprint: The Colonial Book and the Writing of American History, 1790-1855” investigates the role that reprinted colonial texts played in the development of historical consciousness in nineteenth-century America. In the early decades of the nineteenth century, antiquarians and historians began to make a concerted effort to amass and preserve an American archive of manuscript and print material, in addition to other artifacts and “curiosities” from the colonial period. Publishers and editors also began to prepare new editions of colonial texts for publication, introducing nineteenth-century readers to these historical artifacts for the first time. My dissertation considers the role of antiquarian collecting and historical publishing—the reprinting of colonial texts—in the production of popular historical narratives. I study the competing narratives of America’s colonial origins that emerged between 1790 and 1855 as a result of this new commitment to historicism and antiquarianism. I argue that the acts of selecting, editing, and reprinting were ideologically charged as these colonial texts were introduced to new audiences. Instead of functioning as pure reproductions of colonial books, these texts were used to advocate specific religious, political, and cultural positions in the nineteenth century. -

The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College Department of History the Constitution of 1812

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY THE CONSTITUTION OF 1812: AN EXERCISE IN SPANISH CONSTITUTIONAL THOUGHT ALLISON MUCK SPRING 2015 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in History with honors in History Reviewed and approved* by the following: Amy Greenberg Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of History and Women's Studies Thesis Supervisor Michael Milligan Senior Lecturer in History, Director of Undergraduate Studies Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT In March of 1812, the Spanish representative assembly known as the Cortes promulgated a decidedly liberal constitution in the midst of Napoleonic invasion. The Constitution of 1812 governed Spain for the next two years until its abrogation upon the return of Fernando VII. This momentary interval of liberalism appears as an unexpected development in the history of Spain. Undoubtedly, the Constitution’s liberal, progressive, and reformist sentiments differ greatly from the conservative national culture and traditional institutions of Spain at this moment in history. This thesis addresses the causes leading Spain to adopt a constitution intent on empowering the representative Cortes, limiting the Spanish monarchy, and unifying the Spanish nation. Inherent in this project is an analysis of the distinctly Spanish brand of liberalism which attempted to combine both liberal and nationalist sentiments within the Constitution’s provisions. The rhetoric of the Constitution’s drafters claims to be attempting to revive an ancient Spanish constitution and system of government where strong representative institutions and a written constitution upheld the individual rights of the Spanish people. -

The Sovereign States of the Americas Larouche’S Program for Continental Development

LAROUCHE IN 2004 # www.larouchein2004.com The Sovereign States of the Americas LaRouche’s Program for Continental Development Contents PREFACE 2 The Monroe Doctrine Today CHAPTER 1 8 The Deadly Change of 1789-1815 CHAPTER 2 16 Long-Wave Vernadsky Cycles CHAPTER 3 17 Our Planet’s Noëtic Regions CHAPTER 4 20 Fight for the Sovereign Republics of the Americas CHAPTER 5 29 Great Infrastructure Projects for the Americas APPENDIX 38 Synarchism as a System ON THE COVER: Lyndon LaRouche: EIRNS/Stuart Lewis. © September 2003 L04PA-2003-010 Paid for by LaRouche in 2004 EIRNS/Susana Gutierez Barros Lyndon LaRouche addresses a conference in Saltillo, Mexico on Nov. 5, 2002. PREFACE The Monroe Doctrine Today by Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr. September 4, 2003 p to the present date, John Quincy Adams member of the U.S. House of Representatives. remains the most significant of the architects of Throughout this, the leading features of that expressed Uwhat might be fairly distinguished as “the work- genius included his foresight and contributions respect- ing foreign policy of the United States of America.” ing the role of diplomacy in defining the future coast-to- Although he was already a distinguished diplomat coast and north-south borders of the U.S., and in the before joining President Monroe’s Cabinet, his matured crafting of U.S. policy toward the other states of the genius is typified by three of his leading roles in design- Americas. ing our government’s approach to its foreign policies, His role in defining U.S. policy for the Americas, is beginning his part as Secretary of State under President associated, most notably, with three model precedents. -

Mike Bartlett's Future History in King Charles

International Journal of Liberal Arts and Social Science ISSN: 2307-924X www.ijlass.org The Once and Future King: Mike Bartlett’s Future History in King Charles III Ernest Nolan Madonna University Few things are as important to the identity of the British people as their country’s contribution to Western literature and their particular form of constitutional monarchy. Playwright Mike Bartlett pays tribute to both of these themes in his “future-history” play, King Charles III: to Shakespeare, whom Ben Jonson called “Our Star of Poets” and undoubtedly still reigns as the greatest writer in the English language, and to the Royal Family. In fact, Mike Bartlett has said, The idea for King Charles III arrived in my imagination with the form and content very clear, and inextricably linked. It would be a play about the moment Charles takes the throne, and how his conscience would lead him to refuse to sign a bill into law. An epic royal family drama, dealing with power and national constitution, was the content, and therefore the form had surely to be Shakespearean. (“Mike Bartlett: How I Wrote King Charles III”) Bartlett adopts the form of the five-act Shakespearean history play, using blank verse for the scenes involving the Royals—unrhymed iambic pentameter with rhyming couplets at the end of each scene—and plain prose for the scenes involving the commoners. Like Shakespeare, Bartlett also includes a subplot that provides counterpoint to the main action. The story of Prince Harry and Jess, the anti-monarchy young art student whom Harry falls for, brings Harry to the point of wanting to give up his identity as a member of the Royal Family at the same time as the Royal Family itself faces the possibility that the monarchy will not survive if the country is brought to the brink of civil war. -

Bakalářská Práce the Debate Over the Future of the British

Bakalářská práce 2017 Elena Vashchenko Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Bakalářská práce The Debate over the Future of the British Monarchy in Selected Newspapers Elena Vashchenko Plzeň 2017 Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Studijní program Filologie Studijní obor Cizí jazyky pro komerční praxi Kombinace angličtina – ruština Bakalářská práce The Debate over the Future of the British Monarchy in Selected Newspapers Elena Vashchenko Vedoucí práce: Ph.Dr. Alice Tihelková Ph.D. Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Fakulta filozofická Západočeské univerzity v Plzni Plzeň 2017 Prohlašuji, že jsem práci zpracovala samostatně a použila jen uvedených pramenů a literatury. Plzeň, duben 2017 ……………………… Poděkování Mé poděkování patří PhDr. Alici Tihelkové, Ph.D.za odborné vedení, trpělivost a ochotu, kterou mi v průběhu zpracování bakalářské práce věnovala. Plzeň, 24. dubna 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 1 2 THE BRITISH MONARCHY ................................................................... 3 2.1 The definition of monarchy .................................................................... 3 2.2 Constitutional monarchy in the UK ....................................................... 3 2.3 The Royal Family .................................................................................... 5 2.3.1 The Queen ......................................................................................... -

King Charles Iii by Mike Bartlett

KING CHARLES III BY MIKE BARTLETT DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. KING CHARLES III Copyright © 2016, Mike Bartlett All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of KING CHARLES III is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan- American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for KING CHARLES III are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. Inquiries concerning all other rights should be addressed to William Morris Endeavor Entertainment, 11 Madison Ave, 18th floor, New York, NY 10010. -

Catalogue of New Plays 2016–2017

PRESORTED STANDARD U.S. POSTAGE PAID GRAND RAPIDS, MI PERMIT #1 Catalogue of New Plays 2016–2017 ISBN: 978-0-8222-3542-2 DISCOUNTS See page 6 for details on DISCOUNTS for Educators, Libraries, and Bookstores 9 7 8 0 8 2 2 2 3 5 4 2 2 Bold new plays. Recipient of the Obie Award for Commitment to the Publication of New Work Timeless classics. Since 1936. 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016 Tel. 212-683-8960 Fax 212-213-1539 [email protected] OFFICERS Peter Hagan, President Mary Harden, Vice President Patrick Herold, Secretary David Moore, Treasurer Stephen Sultan, President Emeritus BOARD OF DIRECTORS Peter Hagan Mary Harden DPS proudly represents the Patrick Herold ® Joyce Ketay 2016 Tony Award winner and nominees Jonathan Lomma Donald Margulies for BEST PLAY Lynn Nottage Polly Pen John Patrick Shanley Representing the American theatre by publishing and licensing the works of new and established playwrights Formed in 1936 by a number of prominent playwrights and theatre agents, Dramatists Play Service, Inc. was created to foster opportunity and provide support for playwrights by publishing acting editions of their plays and handling the nonprofessional and professional leasing rights to these works. Catalogue of New Plays 2016–2017 © 2016 Dramatists Play Service, Inc. CATALOGUE 16-17.indd 1 10/3/2016 3:49:22 PM Dramatists Play Service, Inc. A Letter from the President Dear Subscriber: A lot happened in 1936. Jesse Owens triumphed at the Berlin Olympics. Edward VIII abdicated to marry Wallis Simpson. The Hindenburg took its maiden voyage. And Dramatists Play Service was founded by the Dramatists Guild of America and an intrepid group of agents. -

Fairy Tale Ending?

FINAL-1 Sat, May 6, 2017 4:00:40 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of May 13 - 19, 2017 Fairy tale ending? Jennifer Morrison stars in “Once Upon a Time” The season’s biggest battle comes to a head in Massachusetts’ First Credit Union the two-part season 6 finale of “Once Upon a Located at 370 HighlandSt. Avenue, Jean's Salem Credit Union ET Filler Time,” airing Sunday, May 14, on ABC. The show that brings beloved fairy-tale characters 3 x 3 1 x 3 TO ADVERTISE HERE to life wraps up many of its storylines this sea- Serving over 15,000 Members • A Part of your Community since 1910 son, as Emma (Jennifer Morrison, “House”) Supporting over 60 Non-Profit Organizations & Programs Contact Glenda battles the Black Fairy (Jaime Murray, “Defi- Serving the Employees of over 40 Businesses 978-338-2540 or [email protected] ance”), and Henry (Jared S. Gilmore, “Mad • Men”) finishes the final chapter of his book. 978.219.1000 www.stjeanscu.com Offices also located in Lynn, Newburyport & Revere Federally Insured by NCUA FINAL-1 Sat, May 6, 2017 4:00:42 PM 2 • Salem News • May 13 - 19, 2017 Closing the book: Season finale of ‘Once Upon a Time’ wraps up storylines By Mary Fournier show is renewed for a seventh sea- ending? Does the end of the book doesn’t necessarily mean that ries that must be wrapped up — it TV Media son. As Henry (Jared S. Gilmore, mean she dies?’” we’re not bringing the cast back, could be tough to tie everything up “Mad Men”) finishes the last Whatever happens, Emma has it’s just: How do you kind of hit the if this does happen to be the final Video releases he finale is here, and the sea- chapter of the book, some of the her loved ones by her side, includ- reset button?” season.