1109 Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to the Paul Maccready Innovative Lives Presentation

Guide to the Paul MacCready Innovative Lives Presentation NMAH.AC.0842 Alison Oswald 2003 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 3 Series : Original Videos (OV 842.1-9), 2002-11-08................................................. 3 Series : Reference Videos, 2002-11-08................................................................... 4 Series 3: Digital images, 2002-11-08....................................................................... 5 Paul MacCready Innovative Lives Presentation NMAH.AC.0842 Collection Overview Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Title: Paul MacCready Innovative Lives Presentation Identifier: -

IGC Plenary 2005

Agenda of the Annual Meeting of the FAI Gliding Commission To be held in Lausanne, Switzerland on 5th and 6th March 2010 Agenda for the IGC Plenary 2010 Day 1, Friday 5th March 2010 Session: Opening and Reports (Friday 09.15 – 10.45) 1. Opening (Bob Henderson) 1.1 Roll Call (Stéphane Desprez/Peter Eriksen) 1.2 Administrative matters (Peter Eriksen) 1.3 Declaration of Conflicts of Interest 2. Minutes of previous meeting, Lausanne, 6th-7th March 2009 (Peter Eriksen) 3. IGC President’s report (Bob Henderson) 4. FAI Matters (Mr.Stéphane Desprez) 4.1 Update by the Secretary General 5. Finance (Dick Bradley) 5.1 2009 Financial report 5.2 Financial statement and budget 6. Reports not requiring voting 6.1 OSTIV report (Loek Boermans) Please note that reports under Agenda items 6.2, 6.3 and 6.4 are made available on the IGC web-site, and will not necessarily be presented. The Committees and Specialists will be available for questions. 6.2 Standing Committees 6.2.1 Communications and PR Report (Bob Henderson) 6.2.2 Championship Management Committee Report (Eric Mozer) 6.2.3 Sporting Code Committee Report (Ross Macintyre) 6.2.4 Air Traffic, Navigation, Display Systems (ANDS) Report (Bernald Smith) 6.2.5 GNSS Flight Recorder Approval Committee (GFAC) Report (Ian Strachan) 6.2.6 FAI Commission on Airspace and Navigation Systems (CANS) Report (Ian Strachan) Session: Reports from Specialists and Competitions (Friday 11.15 – 12.45) 6.3 Working Groups 6.3.1 Country Development Report (Alexander Georgas) 6.3.2 Grand Prix Action Plan (Bob Henderson) 6.3.3 History Committee (Tor Johannessen) 6.3.4 Scoring Working Group (Visa-Matti Leinikki) 6.4 IGC Specialists 6.4.1 CASI Report (Air Sports Commissions) (Tor Johannessen) 6.4.2 EGU/EASA Report (Patrick Pauwels) 6.4.3 Environmental Commission Report (Bernald Smith) 6.4.4 Membership (John Roake) 6.4.5 On-Line Contest Report (Axel Reich) 6.4.6 Simulated Gliding Report (Roland Stuck) 6.4.7 Trophy Management Report (Marina Vigorita) 6.4.8 Web Management Report (Peter Ryder) 7. -

DR. PAUL MACCREADY September 29, 1925 - August 28, 2007 AMA #626304

The AMA History Project Presents: Biography of DR. PAUL MACCREADY September 29, 1925 - August 28, 2007 AMA #626304 Transcribed & Edited by SS (08/2002); Update by JS (02/2017) Career: . Set many model airplane records . First soloed in a powered plane at age 16 . Flew in the U.S. Navy flight-training program during World War II . 1947: Graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in physics from Yale University . Won second place in the National Soaring Contest at Wichita Falls, Texas, at age 21 . 1948, 1949, 1953: Won the U.S. National Soaring Championships . Pioneered high-altitude wave soaring in the U.S. 1956: Became the first American to be an international sailplane champion at a meet in France; represented the U.S. in Europe four times . Invented the MacCready speed ring used worldwide by glider pilots . Earned his master’s degree in physics in 1948 and his doctorate degree in aeronautics in 1952, both from the California Institute of Technology . 1971: Started AeroVironment, Inc. Won a few Henry Kremer Prizes for his cutting-edge designs of planes, such as planes powered by human power only . Early 1980s: Developed solar-powered planes . Received various honors and awards and is affiliated with the National Academy of Engineering, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics and the American Meteorological Society . Served as the international president of the International Human Powered Vehicle Association . Wrote many articles, papers and reports dealing with physics and aeronautics . 2016 AMA Model Aviation Hall of Fame inductee This biography, written in 1986, is stored in the AMA History Project (at the time called the AMA History Program) files. -

Debate Association & Debate Speech National ©

© National SpeechDebate & Association DEBATE 101 Everything You Need to Know About Policy Debate: You Learned Here Bill Smelko & Will Smelko DEBATE 101 Everything You Need to Know About Policy Debate: You Learned Here Bill Smelko & Will Smelko © NATIONAL SPEECH & DEBATE ASSOCIATION DEBATE 101: Everything You Need to Know About Policy Debate: You Learned Here Copyright © 2013 by the National Speech & Debate Association All rights reserved. Published by National Speech & Debate Association 125 Watson Street, PO Box 38, Ripon, WI 54971-0038 USA Phone: (920) 748-6206 Fax: (920) 748-9478 [email protected] No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, now known or hereafter invented, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, information storage and retrieval, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. The National Speech & Debate Association does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, sex, age, gender identity, gender expression, affectional or sexual orientation, or disability in any of its policies, programs, and services. Printed and bound in the United States of America Contents Chapter 1: Debate Tournaments . .1 . Chapter 2: The Rudiments of Rhetoric . 5. Chapter 3: The Debate Process . .11 . Chapter 4: Debating, Negative Options and Approaches, or, THE BIG 6 . .13 . Chapter 5: Step By Step, Or, It’s My Turn & What Do I Do Now? . .41 . Chapter 6: Ten Helpful Little Hints . 63. Chapter 7: Public Speaking Made Easy . -

LOGLINE January / February 2020 Volume 13: Number 1 the Screenwriter’S Ezine

LOGLINE January / February 2020 Volume 13: Number 1 The Screenwriter’s eZine Published by: Letter From the Editor The PAGE International Screenwriting Awards It’s a new year and a new day for screenwriters around the 7190 W. Sunset Blvd. #610 Hollywood, CA 90046 world! Here at PAGE HQ we hope you had a wonderful holiday www.pageawards.com season, feel recharged, and are ready to take the next step in your writing career. In this issue: One way to potentially make a major breakthrough: the 2020 LO PAGE Awards contest. Our Early Entry Deadline is now just 1 Latest News From two weeks away – Monday, January 20 – and with our low the PAGE Awards Early Entry Discount rates, now is the very best time to get your script in the running for one of this year’s awards. Many past PAGE Award winners have optioned and sold their scripts, been signed 2 The Writer’s by Hollywood representatives, and built highly successful careers in the industry. Perspective You could be next! Is It Ever “Too Late” to Chase Your Dream? As we begin lucky Volume 13 of the bimonthly LOGLINE eZine, we welcome new Erin Muroski readers to the publication designed to share industry intel and advice with all writers. First, 2019 PAGE Award winner Erin Muroski reflects on her rush to find success, and how she got over it. PAGE Judge Genie Joseph introduces us to three prevailing story 3 The Judge’s P.O.V. styles that inform a film from page to screen. Script consultant Ray Morton strikes a Three Styles of Story: balance between art and commerce and Dr. -

Canadian Canada $7 Spring 2020 Vol.22, No.2 Screenwriter Film | Television | Radio | Digital Media

CANADIAN CANADA $7 SPRING 2020 VOL.22, NO.2 SCREENWRITER FILM | TELEVISION | RADIO | DIGITAL MEDIA The Law & Order Issue The Detectives: True Crime Canadian-Style Peter Mitchell on Murdoch’s 200th ep Floyd Kane Delves into class, race & gender in legal PM40011669 drama Diggstown Help Producers Find and Hire You Update your Member Directory profile. It’s easy. Login at www.wgc.ca to get started. Questions? Contact Terry Mark ([email protected]) Member Directory Ad.indd 1 3/6/19 11:25 AM CANADIAN SCREENWRITER The journal of the Writers Guild of Canada Vol. 22 No. 2 Spring 2020 Contents ISSN 1481-6253 Publication Mail Agreement Number 400-11669 Cover Publisher Maureen Parker Diggstown Raises Kane To New Heights 6 Editor Tom Villemaire [email protected] Creator and showrunner Floyd Kane tackles the intersection of class, race, gender and the Canadian legal system as the Director of Communications groundbreaking CBC drama heads into its second season Lana Castleman By Li Robbins Editorial Advisory Board Michael Amo Michael MacLennan Features Susin Nielsen The Detectives: True Crime Canadian-Style 12 Simon Racioppa Rachel Langer With a solid background investigating and writing about true President Dennis Heaton (Pacific) crime, showrunner Petro Duszara and his team tell us why this Councillors series is resonating with viewers and lawmakers alike. Michael Amo (Atlantic) By Matthew Hays Marsha Greene (Central) Alex Levine (Central) Anne-Marie Perrotta (Quebec) Murdoch Mysteries’ Major Milestone 16 Lienne Sawatsky (Central) Andrew Wreggitt (Western) Showrunner Peter Mitchell reflects on the successful marriage Design Studio Ours of writing and crew that has made Murdoch Mysteries an international hit, fuelling 200+ eps. -

Artist's Proposal

Gabbert Artist’s Proposal 14th Street Roundabout Page 434 of 1673 Gabbert Sarasota Roundabout 41&14th James Gabbert Sculptor Ladies and Gentlemen, Thank you for this opportunity. For your consideration I propose a work tentatively titled “Flame”. I believe it to be simple-yet- compelling, symbolic, and appropriate to this setting. Dimensions will be 20 feet high by 14.5 feet wide by 14.5 feet deep. It sits on a 3.5 feet high by 9 feet in diameter base. (not accurately dimensioned in the 3D graphics) The composition. The design has substance, and yet, there is practically no impediment to drivers’ visibility. After review of the design by a structural engineer the flame flicks may need to be pierced with openings to meet the 150 mph wind velocity requirement. I see no problem in adjusting the design to accommodate any change like this. Fire can represent our passions, zeal, creativity, and motivation. The “flame” can suggest the light held by the Statue of Liberty, the fire from Prometheus, the spirit of the city, and the hearth-fire of 612.207.8895 | jgsculpture.webs.com | [email protected] 14th Street Roundabout Page 435 of 1673 Gabbert Sarasota Roundabout 41&14th James Gabbert Sculptor home. It would be lit at night with a soft glow from within. A flame creates a sense of place because everyone is drawn to a fire. A flame sheds light and warmth. Reference my “Hopes and Dreams” in my work example to get a sense of what this would look like. The four circles suggest unity and wholeness, or, the circle of life, or, the earth/universe. -

Interview with Paul B. Maccready

PAUL B. MACCREADY (1925 - 2007) INTERVIEWED BY SARA LIPPINCOTT February – March 2003 ARCHIVES CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Pasadena, California Subject area Engineering, aeronautics Abstract An interview in three sessions with Paul B. MacCready, Caltech graduate (MS physics, 1948; PhD aeronautics, 1952) and inventor and entrepreneur who became internationally known in 1977 as the “father of human-powered flight.” Conducted by Sara Lippincott, the oral history covers MacCready’s scientific and entrepreneurial career, including biographical details. MacCready discusses his family life, early education and aeronautical interests in New Haven, CT. During his youth he progressed from the construction of model airplanes to the flying of motor-propelled aircraft and gliders. MacCready recounts his soaring competitions along with his education at Yale in the 1940s; he continues by describing his graduate work at Caltech from 1947 to 1952 and his high altitude soaring in the Sierras and Europe; he relates this to his interest in weather modification and his entrepreneurial work in cloud seeding. In 1971 MacCready founded AeroVironment with his associates Peter Lissaman and Ivar Tombach; he discusses his early clients and research. Beginning in the mid-1970s MacCready began work on the celebrated Gossamer aircraft series; the interview includes discussion concerning the advent of the Gossamer Condor in 1976-1977 and the flight of the Gossamer Albatross across the English Channel in 1979. The interview also includes his continued interest in http://resolver.caltech.edu/CaltechOH:OH_MacCready_P human-powered flight and environmental issues, as well as unmanned solar- powered flight. Administrative information Access The interview is unrestricted. Copyright Copyright has been assigned to the California Institute of Technology © 2006, 2007. -

Full Beacher

THE April 13, 2006 THE CENTURY 21 Long Beach Realty TM 1401 Lake Shore Drive ~ 3100 Lake Shore Drive 123 (219) 874-5209 ~ (219) 872-1432 911 Franklin Street Weekly Newspaper Michigan City, IN 46360 T www.c21longbeachrealty.com Open 7 Days a Week 2207 Lake Shore Drive, Long Beach Volume 22, Number 14 Thursday, April 13, 2006 Wetomachek built in 1924 and renamed Mary Hill in 1946, this substantially built Dutch Colonial enjoys the charm and grace of yester- year. On 80 feet of hillside Lake Shore Drive property, views over Lake Michigan reach from Illinois to Michigan. Huge living room with wood burning fireplace opens to 640 feet of wrap around glass enclosed porch with handsome pillars and charming Hoosier fireplace. Redwood walls and ceilings in huge dining room. Family sized kitchen. Eight rooms include over 2700 square feet of living area. Wood floors, redwood paneling, drywall over plaster walls. Ceramic baths. Double garage. Charming playhouse and extra parking is off of Round About Easter NEW LISTING one way street at rear. For the buyer who appreciates charm and quality; here is Round about Eastertime, Round about Easter perfection. $1,300,000 Quick as a wink, You’ll thrill to the stir Ribbon grass freshens Of catkins wakening, And flowers turn pink. Starting to purr. Eggs in their baskets Robins returning Take on overnight Will carol new cheer, Strangest of colors Bluebells start ringing – Artistically bright. Glad Easter is here. Bunnies go hippity – Hopping about, 4967 Remington Square, LaPorte 409 Coolspring Avenue, Michigan City Trees in the woodlands 1 Energy Star Rated spacious 4 bedroom, 2 ⁄2 bath home on Bright, Spacious, and Inviting two story just a short walk from a corner lot in Hunters Run subdivision. -

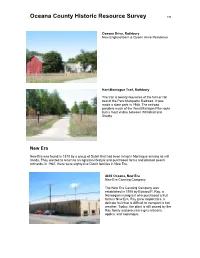

West Michigan Pike Route but Is Most Visible Between Whitehall and Shelby

Oceana County Historic Resource Survey 198 Oceana Drive, Rothbury New England Barn & Queen Anne Residence Hart-Montague Trail, Rothbury The trail is twenty-two miles of the former rail bed of the Pere Marquette Railroad. It was made a state park in 1988. The railroad parallels much of the West Michigan Pike route but is most visible between Whitehall and Shelby. New Era New Era was found in 1878 by a group of Dutch that had been living in Montague serving as mill hands. They wanted to return to an agrarian lifestyle and purchased farms and planted peach orchards. In 1947, there were eighty-five Dutch families in New Era. 4856 Oceana, New Era New Era Canning Company The New Era Canning Company was established in 1910 by Edward P. Ray, a Norwegian immigrant who purchased a fruit farm in New Era. Ray grew raspberries, a delicate fruit that is difficult to transport in hot weather. Today, the plant is still owned by the Ray family and processes green beans, apples, and asparagus. Oceana County Historic Resource Survey 199 4775 First Street, New Era New Era Reformed Church 4736 First Street, New Era Veltman Hardware Store Concrete Block Buildings. New Era is characterized by a number of vernacular concrete block buildings. Prior to 1900, concrete was not a common building material for residential or commercial structures. Experimentation, testing and the development of standards for cement and additives in the late 19th century, led to the use of concrete a strong reliable building material after the turn of the century. Concrete was also considered to be fireproof, an important consideration as many communities suffered devastating fires that burned blocks of their wooden buildings Oceana County Historic Resource Survey 200 in the late nineteenth century. -

The Complexities of Latina Sexuality on Ugly Betty Tanya González

IS UGLY THE NEW SEXY? The Complexities of Latina Sexuality on Ugly Betty Tanya González ABC’s Emmy and Golden Globe winning television show Ugly Betty stars America Ferrera as Betty Suarez, an intelligent Mexican American executive assistant who lives in Queens, New York, but works at Mode in Manhattan. An adaptation from the Colombian telenovela,Yo soy, Betty la fea, this television show works on a fairy tale premise: the ugly protagonist with a heart of gold will eventually obtain happiness by virtue of her goodness. However, Ugly Betty offers a protagonist with multiple love interests, constantly involving her in a variety of love triangles, begging the question, “Is ugly the new sexy?” The following analysis of Betty as a sexual subject demonstrates that Ugly Betty, within the limits of Hollywood representation, offers complex subjects instead of one-dimensional types. The show’s use of a Latino camp aesthetic continually introduces elements, like Betty’s sexuality, that push the limits of how we perceive Latinas/os on television and in everyday life. As a result, Ugly Betty surprisingly illustrates Chicana/o and Latina/o feminist theories about identity construction. ABC’s Emmy and Golden Globe winning television show Ugly Betty is a global iteration of the Colombian telenovela1 phenomenon Yo soy, Betty la fea (1999-2001). Ugly Betty, which premiered Fall 2006 and will end Spring 2010, stars America Ferrera as Betty Suarez, an intelligent, sweet, perky young Latina2 who lives in Queens, but works at Mode, a fictional representation of Vogue magazine. As the title suggests, people perceive Betty as ugly because she is not model-skinny; wears glasses, braces, and bangs; and has poor fashion sense. -

Of Public Art in Richland?

2020 Richland, WA Public Art Survey SurveyMonkey Q1 What are your favorite example(s) of public Art in Richland? Answered: 427 Skipped: 7 Murals/sculptur es on the si... Artistic design... Sculptures placed in... Performance Art/Special... Art placed in roundabouts Vinyl Art Wraps on... Other (please specify) 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% ANSWER CHOICES RESPONSES Murals/sculptures on the side of buildings 64.64% 276 Artistic design incorporated into infrastructure (ex: benches, bridges, fences, etc) 58.55% 250 Sculptures placed in parks, along trails or at City facilities 56.67% 242 Performance Art/Special Events supporting Art 46.84% 200 Art placed in roundabouts 34.43% 147 Vinyl Art Wraps on Traffic Utility Cabinets 29.27% 125 Other (please specify) 5.15% 22 Total Respondents: 427 1 / 69 2020 Richland, WA Public Art Survey SurveyMonkey # OTHER (PLEASE SPECIFY) DATE 1 public glassblowing 1/15/2021 12:52 PM 2 Ye Merry Greenwood Faire 1/13/2021 12:18 PM 3 Spaces for litterateur and dialogue 1/12/2021 2:36 PM 4 Privately funded art 1/12/2021 2:05 PM 5 Skateparks 1/11/2021 9:01 PM 6 Folk art by residents in yards etc 1/11/2021 8:30 PM 7 Any examples of public art only adds to the enhancement of our community and moves us into 1/11/2021 3:52 PM the realm of cultural awareness and appreciation. It shows a level of sophistication and thinking and awareness of a larger picture than merely that of our own lives and self-centered thinking.