Francesco Mancini Solos for a Flute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NYRO 2004 Booklet.Pub

Society of Recorder Players Charity no 282751 Helen Hooker Information booklet Designed by Helen Beare Price £2 activities workshops serious study music & residential courses instruments Recorder recorder orchestras www.srp.org.uk This page is blank www.srp.org.uk President Sir Peter Maxwell Davies CBE Chairmain Andrew Short, 12 Woodburn Terrace, Edinburgh, EH10 4SJ [email protected] Secretary Alistair Read, 6 Upton Court, 56 East Dulwich Grove, London SE2 8PS The SRP is a registered charity, no 282751 The first version of this booklet was compiled for the National Youth Recorder Orchestra 2003 so that young players could learn more about what is happening in the recorder world in the UK, contribute to and extend it. NYRO 2003 was funded by Youth Music as part of their outreach programme. The SRP committee decided in 2003 that it would be useful for further copies to be produced for general use. In 2004 a copy, free of charge, is being supplied to each member of the SRP funded by the Arthur Ingram legacy to the Society. The booket’s information will also be on the SRP website. Every effor has been made to include suppliers, courses and other information, and omissions are unintended. One-day workshops and playdays are not included in the booklet. Readers should check the SRP website, the Recorder Magazine and SRP branch Secretaries for up-to-date information and workshops. With thanks to Davide Beare, Andrew Short, Ashley Allerton, David Scruby and Jeremy Burbridge for their help, SRP Branch Secretaries for their involvement, Harry Routledge for illustrations, and above all to the Arthur Ingram legacy. -

DBE Participation Commitment(S)

Attachment A Attachment B Pre-Proposal Conference for RFP 8-2039 Operations & Maintenance Services for the OC Streetcar Project Orange County Transportation Authority Agenda • Introductions • Safety/Emergency Evacuation • Online Business and Networking Tools • Key Procurement Information & Dates • Review of RFP Documents • Disadvantaged Business Enterprise (DBE) Requirements • Scope of Work • Questions and Answer 2 CAMM NET Registration Why register on CAMM NET? https://cammnet.octa.net/ • To receive e-mail notifications of Solicitations, Addenda and Awards • View and update your vendor profile • Required for Award 3 Online Business & Networking Tools • CAMM NET Connect • https://www.facebook.com/CammnetConnect • Working with OCTA • https://cammnet.octa.net/about-us/working/ • Planholder’s List • https://cammnet.octa.net/procurements/planholders-list-selection/ • Disadvantaged Business Enterprise (DBE) Program • https://cammnet.octa.net/dbe/ 4 Key Procurement Dates Written Questions Due: January 3, 2019 OCTA Responds: January 17, 2019 Proposals Due: February 12, 2019 2:00 PM Interviews: April 23, 2019 Board of Directors Award: November 25, 2019 5 Key Procurement Information • All questions/contact with Authority staff should be directed to the assigned Senior Contract Administrator, Irene Green. • Next Addendum will contain a copy of the Pre-Proposal sign-in sheet and today’s presentation • Award based on prime-sub relationship, not joint ventures • Contract term is for approximately 7 years; with 2, 2-year options • Funded with Federal Transit Administration (FTA) funds • DBE participation goal is 4% 6 Guidelines for Written Questions • Questions must be submitted directly to Irene Green, Senior Contract Administrator, in writing, by: January 3, 2019, 5:00 p.m. • E-mail recommended: [email protected] • Any changes Authority makes to procurement documents will be by written Addenda only • Addenda will be issued via CAMM NET • Today’s Verbal discussions today are non-binding 7 Next… Proposal Instructions Followed by …. -

SOUND EDUCATION Secondary Ensemble

SOUND EDUCATION Secondary Ensemble INTEGRAL MUSIC EDUCATION The explorations, free play and concentrated practices with sound and music should find their dedicated place and space in every educational The experience of recent decades in Music Education worldwide has environment to enhance the individual, group and social development and shown that culturally sensitized and integrative new approaches work ex- competency. traordinary well in imparting to the young generation the sense of wonder for music, the principles of harmony and the possibilities for a creative and SECONDARY INSTRUMENTS fulfilled life. This prepared ensemble of instruments is based on a careful selection We work toward a synthesis of innovative and traditional practices to devel - representing the different categories and types of instruments. Through it op an integral approach to curriculum development, learning materials and a full exposure of an original instrument circle with its diverse opportunities methodologies including a selected range of World Music Instruments. Based for free play and improvisation can be offered to the growing youth. on the qualities of different materials (stone, clay, wood, bamboo, reed, metal, glass) and the diverse ways of sound production (flutes, solids, strings, skins The instruments are ordered according to standard classification of aero- and voice) with a correlation with the elements (air, fire, water, earth and phones (winds), chordophones (strings), idiophones (percussion), mem- ether) a variable framework is set for creative encounter with and deepening branophones (skins), and nature sounds/atmospherics to encompass all research into the uniquely human faculty of musical expression. elements and parts of the being in an integration of head, heart and hara, mental cognition, vital emotion and physical perception and movement. -

At Tony Lena's, It's All in the Bread

TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 18, 2020 A world 828 units connected oated by trains for South Marblehead store owner nds perfect Harbor model in Peabody By Gayla Cawley ITEM STAFF By Thor Jourgensen ITEM STAFF LYNN — After years of stalled plans aimed at redeveloping the PEABODY — A train lover since long-vacant 17-acre waterfront site he was tyke, Don Stubbs decided known as “South Harbor” on the to turn a hobby into a business in Lynnway, the city’s head of econom- 1988 when he opened North East ic development believes the timing Trains on Main Street, about four is nally right. blocks from the model and minia- The renewed push to redevelop ture train store’s current location. the South Harbor site, which has Located in a former hardware sat vacant for three decades and is store with high, tin-stamp ceil- located near the General Edwards ings and classical music playing Bridge at the mouth of the Saugus at a soft volume, North East is a River, comes from property owner model-train lover’s dream come Joseph O’Donnell, who purchased true. Display cases and shelves the land in 2005. showcase miniature locomotives, O’Donnell, founder of Belmont passenger and freight cars with Capital, LLC in Cambridge, has names like “K-line diesel” and submitted preliminary plans that “Jordan spreader plow.” would transform the former Harbor A walk around the store is a vis- House site into a neighborhood of it to a world where rail enthusi- 828 market-rate apartments over asts from around the region stop three wood-framed buildings, retail in to shop or sell their train col- space and 935 parking spaces. -

Tajuk Perkara Malaysia: Perluasan Library of Congress Subject Headings

Tajuk Perkara Malaysia: Perluasan Library of Congress Subject Headings TAJUK PERKARA MALAYSIA: PERLUASAN LIBRARY OF CONGRESS SUBJECT HEADINGS EDISI KEDUA TAJUK PERKARA MALAYSIA: PERLUASAN LIBRARY OF CONGRESS SUBJECT HEADINGS EDISI KEDUA Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia Kuala Lumpur 2020 © Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia 2020 Hak cipta terpelihara. Tiada bahagian terbitan ini boleh diterbitkan semula atau ditukar dalam apa jua bentuk dan dengan apa jua sama ada elektronik, mekanikal, fotokopi, rakaman dan sebagainya sebelum mendapat kebenaran bertulis daripada Ketua Pengarah Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia. Diterbitkan oleh: Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia 232, Jalan Tun Razak 50572 Kuala Lumpur Tel: 03-2687 1700 Faks: 03-2694 2490 www.pnm.gov.my www.facebook.com/PerpustakaanNegaraMalaysia blogpnm.pnm.gov.my twitter.com/PNM_sosial Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia Data Pengkatalogan-dalam-Penerbitan TAJUK PERKARA MALAYSIA : PERLUASAN LIBRARY OF CONGRESS SUBJECT HEADINGS. – EDISI KEDUA. Mode of access: Internet eISBN 978-967-931-359-8 1. Subject headings--Malaysia. 2. Subject headings, Malay. 3. Government publications--Malaysia. 4. Electronic books. I. Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia. 025.47 KANDUNGAN Sekapur Sirih Ketua Pengarah Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia i Prakata Pengenalan ii Objektif iii Format iv-v Skop vi-viii Senarai Ahli Jawatankuasa Tajuk Perkara Malaysia: Perluasan Library of Congress Subject Headings ix Senarai Tajuk Perkara Malaysia: Perluasan Library of Congress Subject Headings Tajuk Perkara Topikal (Tag 650) 1-152 Tajuk Perkara Geografik (Tag 651) 153-181 Bibliografi 183-188 Tajuk Perkara Malaysia: Perluasan Library of Congress Subject Headings Sekapur Sirih Ketua Pengarah Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia Syukur Alhamdulillah dipanjatkan dengan penuh kesyukuran kerana dengan izin- Nya Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia telah berjaya menerbitkan buku Tajuk Perkara Malaysia: Perluasan Library of Congress Subject Headings Edisi Kedua ini. -

Redefining the Food and Beverage Landscape by Providing a Visionary

Redefining the Food and Beverage landscape by providing a visionary platform for entrepreneurs and building a sustainable ecosystem for the industry Page C Page 1 PubsNote The Concept of Change is to Focus your Energy on Building The New One of the essential qualities of As for our CSR programme, it hospitality is the concept of change. has been a year since we introduced Nothing remains constant for long a Chemo Graduation Ball for and the Hospitality Asia team is children who have completed their conscious of this, as we document chemotherapy treatment journey who and what is at the cutting edge at the University Malaya Medical of the food and beverage industry, in Centre (UMMC). Words cannot one of the most dynamic regions in express how my team and I felt to the world. see happy smiles on these children’s Change comes about through faces upon receiving their graduation breaking boundaries, individuals certificate – a small step taken by and organisations pushing limits HAPA to applaud their courage, and testing new techniques, determination and positive spirit, ingredients, styles and concepts. in undergoing such a challenging Collectively known as entrepreneurs, journey. we are constantly impressed with achievements made by Last year, HAPA raised a total of RM180,000 for people and organisations and, as such, we are launching the Chemo Graduation Ball whereby funds were also a new HAPA series to recognise the region’s innovative channeled to UMMC and Hospital KL for medication, entrepreneurs – The HAPA Entrepreneur Awards 2018- medical equipment, cancer research and chemo treatment 2019. Nominations are now being called with more details for children with cancer. -

Wye---A-History-Of-The-Flute.Pdf

A History of the Flute Trevor Wye 1. Whistles What a daunting prospect to write a simple flute history without missing anything. Looking at a pamphlet a few years ago, it stated that in the South Pacific Islands, those tiny islands south of Hawai, there are about 1300 different named flutes. Our modern flute is just one of thousands of flutes worldwide of all shapes and sizes from miniature ocarinas to giants like the Slovakian Fujara. A sensible way to begin would be to understand how flutes are made to emit sound and so we will look at the four main varieties. These are Endblown where the player blows across the end of the tube; Sideblown as in our modern flute; a Fipple or encapsulated such as is found in a referee's whistle and a Globular flute such as in ocarinas and gemshorns. In all cases, the air is directed against a sharp edge which causes the air to alternate between entering the tube where it meets resistance, then shifting to going outside the tube. This alternation takes place at great speed causing the air inside the tube or vessel to vibrate and so make a sound. In the endblown flute shown below, the tube is held upright and the air directed across the cutaway top of the tube. The fipple flute is sounded by the player directing air through a tube or windway against the sharp edge. An example is the recorder and the pitch is changed by covering the holes down the tube in succession. Globular flutes are sounded either by blowing across a hole or via the fipple which is connected to the 'globe' shown above, though the way the instrument responds is unlike the whistle; the notes can be changed by uncovering any hole, no matter in what position it is placed. -

Musical Practices in the Balkans: Ethnomusicological Perspectives

MUSICAL PRACTICES IN THE BALKANS: ETHNOMUSICOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES МУЗИЧКЕ ПРАКСЕ БАЛКАНА: ЕТНОМУЗИКОЛОШКЕ ПЕРСПЕКТИВЕ СРПСКА АКАДЕМИЈА НАУКА И УМЕТНОСТИ НАУЧНИ СКУПОВИ Књига CXLII ОДЕЉЕЊЕ ЛИКОВНЕ И МУЗИЧКЕ УМЕТНОСТИ Књига 8 МУЗИЧКЕ ПРАКСЕ БАЛКАНА: ЕТНОМУЗИКОЛОШКЕ ПЕРСПЕКТИВЕ ЗБОРНИК РАДОВА СА НАУЧНОГ СКУПА ОДРЖАНОГ ОД 23. ДО 25. НОВЕМБРА 2011. Примљено на X скупу Одељења ликовне и музичке уметности од 14. 12. 2012, на основу реферата академикâ Дејана Деспића и Александра Ломе У р е д н и ц и Академик ДЕЈАН ДЕСПИЋ др ЈЕЛЕНА ЈОВАНОВИЋ др ДАНКА ЛАЈИЋ-МИХАЈЛОВИЋ БЕОГРАД 2012 МУЗИКОЛОШКИ ИНСТИТУТ САНУ SERBIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND ARTS ACADEMIC CONFERENCES Volume CXLII DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS AND MUSIC Book 8 MUSICAL PRACTICES IN THE BALKANS: ETHNOMUSICOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES PROCEEDINGS OF THE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE HELD FROM NOVEMBER 23 TO 25, 2011 Accepted at the X meeting of the Department of Fine Arts and Music of 14.12.2012., on the basis of the review presented by Academicians Dejan Despić and Aleksandar Loma E d i t o r s Academician DEJAN DESPIĆ JELENA JOVANOVIĆ, PhD DANKA LAJIĆ-MIHAJLOVIĆ, PhD BELGRADE 2012 INSTITUTE OF MUSICOLOGY Издају Published by Српска академија наука и уметности Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts и and Музиколошки институт САНУ Institute of Musicology SASA Лектор за енглески језик Proof-reader for English Јелена Симоновић-Шиф Jelena Simonović-Schiff Припрема аудио прилога Audio examples prepared by Зоран Јерковић Zoran Jerković Припрема видео прилога Video examples prepared by Милош Рашић Милош Рашић Технички -

(EN) SYNONYMS, ALTERNATIVE TR Percussion Bells Abanangbweli

FAMILY (EN) GROUP (EN) KEYWORD (EN) SYNONYMS, ALTERNATIVE TR Percussion Bells Abanangbweli Wind Accordions Accordion Strings Zithers Accord‐zither Percussion Drums Adufe Strings Musical bows Adungu Strings Zithers Aeolian harp Keyboard Organs Aeolian organ Wind Others Aerophone Percussion Bells Agogo Ogebe ; Ugebe Percussion Drums Agual Agwal Wind Trumpets Agwara Wind Oboes Alboka Albogon ; Albogue Wind Oboes Algaita Wind Flutes Algoja Algoza Wind Trumpets Alphorn Alpenhorn Wind Saxhorns Althorn Wind Saxhorns Alto bugle Wind Clarinets Alto clarinet Wind Oboes Alto crumhorn Wind Bassoons Alto dulcian Wind Bassoons Alto fagotto Wind Flugelhorns Alto flugelhorn Tenor horn Wind Flutes Alto flute Wind Saxhorns Alto horn Wind Bugles Alto keyed bugle Wind Ophicleides Alto ophicleide Wind Oboes Alto rothophone Wind Saxhorns Alto saxhorn Wind Saxophones Alto saxophone Wind Tubas Alto saxotromba Wind Oboes Alto shawm Wind Trombones Alto trombone Wind Trumpets Amakondere Percussion Bells Ambassa Wind Flutes Anata Tarca ; Tarka ; Taruma ; Turum Strings Lutes Angel lute Angelica Percussion Rattles Angklung Mechanical Mechanical Antiphonel Wind Saxhorns Antoniophone Percussion Metallophones / Steeldrums Anvil Percussion Rattles Anzona Percussion Bells Aporo Strings Zithers Appalchian dulcimer Strings Citterns Arch harp‐lute Strings Harps Arched harp Strings Citterns Archcittern Strings Lutes Archlute Strings Harps Ardin Wind Clarinets Arghul Argul ; Arghoul Strings Zithers Armandine Strings Zithers Arpanetta Strings Violoncellos Arpeggione Keyboard -

10 Chapter 4.Pdf

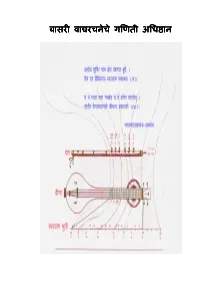

बासर/ वारचनेचे गDणती अिध%ान ूकरण चौथे बासर/ वारचनेचे गDणती अअअिधअिधिधिध%ान%ान%ान%ान MATHEMATICAL CALCULATIONS FOR TRADITIONAL HINDUSTANI BANSURI OF SIX TONE HOLES Mathematical Calculations for Traditional Hindustani 6 Tone Hole Flute* Determining approximate finger hole locations for a traditional 6 tone hole flute (i.e. 1 blow hole and 6 tone holes total 7 holes) is somewhat complicated. The wavelength of sound produced is determined by the flute tube and tone holes. For a pipe of length L, open at both ends, and ignoring end effects, the wavelength of sound is twice the length of the tube. The frequency produced is given by dividing the speed of sound (345 m/s) at 25 C by the wavelength. The method described here is to estimate an effective length for a real (cylindrical) tube taking into account end effects, the size of tone holes, etc. Let’s discuss the basic anatomy of a primitive flute, the geometries that are involved, and name and number the holes. १८५ The basic flute is constructed of a single tube with a stopper at one end (typically cork.) This discussion will refer to this end as the “Close” end. The close end is also the end which will have the blow hole. The blow hole is the hole the instrumentalist will blow across to generate the sound (it’s the hole the player blows across.) The blow hole is located just beside the stopper. The other end of the flute is open and will be called the “Open” end. -

Detailed Instrument List & Descriptions

DIRECTORY OF INSTRUMENTS IN GARRITAN WORLD INSTRUMENTS 66 THE WIND INSTRUMENTS ARIA name: Description: Controls: Africa Arghul The Arghul is a reed woodwind instrument that Vel (attack), MW consists of two asymmetrical pipes. One pipe, (vol/eq), Porta, a chanter with between five and seven finger Lgth, VAR1, holes, is dedicated to the melody. The second VAR2, FiltLv, pipe, longer than the first, produces a drone. FiltFq, VibSpd, Arghuls come in different sizes and are played in Vib Amt, AirNs, Egypt and surrounding regions. Fluttr, Auto- • Range: C3- C6 Legato, BndSpd, Keyswitches Mijwiz 1 The Mijwiz is a traditional instrument of Egypt Vel (attack), MW and is one of the oldest wind instruments. Its (vol/eq), Porta, name means “dual” as it consists of two short Lgth, VAR1, bamboo reed pipes tied together. Instead of hav- VAR2, FiltLv, ing a separate reed attached to a mouthpiece, FiltFq, VibSpd, the reed in the Mijwiz is a vibrating tongue Vib Amt, AirNs, made from a slit cut into the wall of the instru- Fluttr, Auto- ment itself. Legato, BndSpd, • Range: C3 - C6 Keyswitches Mijwiz 2 Another Mijwiz instrument with a different Vel (attack), MW range and character. (vol/eq), Porta, • Range: C4 - C6 Lgth, VAR1, VAR2, FiltLv, FiltFq, VibSpd, Vib Amt, AirNs, Fluttr, Auto- Legato, BndSpd, Keyswitches A User’s Guide to Garritan World Instruments THE WIND INSTRUMENTS ARIA name: Description: Controls: China Bawu The Bawu is a side-blown wind instrument Vel (attack), MW found throughout China. Although it re- (vol/eq), Porta, Lgth, sembles a flute, it is actually a reed instrument. -

Library Orders - Music Composition/Electronic Music

LIBRARY ORDERS - MUSIC COMPOSITION/ELECTRONIC MUSIC COMPOSER PRIORITY TITLE FORMAT PUBLISHER PRICE In Collection? Babbitt, Milton A Three Compositions for Piano score Boelke-Bomart 9.50 Bartok, Bela A Mikrokosmos; progressive piano pieces. Vol. 1, NEW DEFINITIVE ED score Boosey & Hawkes Inc. 0.00 YES Bartok, Bela A Mikrokosmos; progressive piano pieces. Vol. 2, NEW DEFINITIVE ED score Boosey & Hawkes Inc. 0.00 YES Bartok, Bela A Mikrokosmos; progressive piano pieces. Vol. 3, NEW DEFINITIVE ED score Boosey & Hawkes Inc. 0.00 YES Bartok, Bela A Mikrokosmos; progressive piano pieces. Vol. 4, NEW DEFINITIVE ED score Boosey & Hawkes Inc. 0.00 YES Bartok, Bela A Mikrokosmos; progressive piano pieces. Vol. 5, NEW DEFINITIVE ED score Boosey & Hawkes Inc. 0.00 YES Bartok, Bela A Mikrokosmos; progressive piano pieces. Vol. 6, NEW DEFINITIVE ED score Boosey & Hawkes Inc. 0.00 YES Bartok, Bela A Music for strings, percussion, and celesta score Boosey & Hawkes Inc. 0.00 YES Berbarian, Cathy A Stripsody : for solo voice score C.F. Peters Corp. 18.70 Berg, Alban A Violin Concerto score Warner Brothers Music Pub. 0.00 YES Berio, Luciano A Sequenza V, for trombone score Warner Brothers Music Pub. 19.95 Berio, Luciano A Sequenza VII; per oboe solo score Warner Brothers Music Pub. 15.95 Berio, Luciano A Sequenza XII : per bassoon solo score Warner Brothers Music Pub. 35.00 Berio, Luciano A Sinfonia, for eight voices and orchestra score Warner Brothers Music Pub. 125.00 Boulez, Pierre A Marteau sans maître : pour voix d'alto et 6 instruments score Warner Brothers Music Pub.