Rickettsioses: a Continuing Disease Problem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parinaud's Oculoglandular Syndrome

Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease Case Report Parinaud’s Oculoglandular Syndrome: A Case in an Adult with Flea-Borne Typhus and a Review M. Kevin Dixon 1, Christopher L. Dayton 2 and Gregory M. Anstead 3,4,* 1 Baylor Scott & White Clinic, 800 Scott & White Drive, College Station, TX 77845, USA; [email protected] 2 Division of Critical Care, Department of Medicine, University of Texas Health, San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA; [email protected] 3 Medical Service, South Texas Veterans Health Care System, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA 4 Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, University of Texas Health, San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-210-567-4666; Fax: +1-210-567-4670 Received: 7 June 2020; Accepted: 24 July 2020; Published: 29 July 2020 Abstract: Parinaud’s oculoglandular syndrome (POGS) is defined as unilateral granulomatous conjunctivitis and facial lymphadenopathy. The aims of the current study are to describe a case of POGS with uveitis due to flea-borne typhus (FBT) and to present a diagnostic and therapeutic approach to POGS. The patient, a 38-year old man, presented with persistent unilateral eye pain, fever, rash, preauricular and submandibular lymphadenopathy, and laboratory findings of FBT: hyponatremia, elevated transaminase and lactate dehydrogenase levels, thrombocytopenia, and hypoalbuminemia. His condition rapidly improved after starting doxycycline. Soon after hospitalization, he was diagnosed with uveitis, which responded to topical prednisolone. To derive a diagnostic and empiric therapeutic approach to POGS, we reviewed the cases of POGS from its various causes since 1976 to discern epidemiologic clues and determine successful diagnostic techniques and therapies; we found multiple cases due to cat scratch disease (CSD; due to Bartonella henselae) (twelve), tularemia (ten), sporotrichosis (three), Rickettsia conorii (three), R. -

Know Your Abcs: a Quick Guide to Reportable Infectious Diseases in Ohio

Know Your ABCs: A Quick Guide to Reportable Infectious Diseases in Ohio From the Ohio Administrative Code Chapter 3701-3; Effective August 1, 2019 Class A: Diseases of major public health concern because of the severity of disease or potential for epidemic spread – report immediately via telephone upon recognition that a case, a suspected case, or a positive laboratory result exists. • Anthrax • Measles • Rubella (not congenital) • Viral hemorrhagic fever • Botulism, foodborne • Meningococcal disease • Severe acute respiratory (VHF), including Ebola virus • Cholera • Middle East Respiratory syndrome (SARS) disease, Lassa fever, Marburg • Diphtheria Syndrome (MERS) • Smallpox hemorrhagic fever, and • Influenza A – novel virus • Plague • Tularemia Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic infection • Rabies, human fever Any unexpected pattern of cases, suspected cases, deaths or increased incidence of any other disease of major public health concern, because of the severity of disease or potential for epidemic spread, which may indicate a newly recognized infectious agent, outbreak, epidemic, related public health hazard or act of bioterrorism. Class B: Disease of public health concern needing timely response because of potential for epidemic spread – report by the end of the next business day after the existence of a case, a suspected case, or a positive laboratory result is known. • Amebiasis • Carbapenemase-producing • Hepatitis B (perinatal) • Salmonellosis • Arboviral neuroinvasive and carbapenem-resistant • Hepatitis C (non-perinatal) • Shigellosis -

Melioidosis in Northern Tanzania: an Important Cause of Febrile Illness?

Melioidosis and serological evidence of exposure to Burkholderia pseudomallei among patients with fever, northern Tanzania Michael Maze Department of Medicine University of Otago, Christchurch Melioidosis Melioidosis caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei • Challenging to identify when cultured Soil reservoir, with human infection from contact with contaminated water Most infected people are asymptomatic: 1 clinical illness for 4,500 antibody producing exposures Febrile illness with a variety of presentations and bacteraemia is present in 40-60% of people with acute illness Estimated 89,000 deaths globally Gavin Koh CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4975784 Laboratory diagnosis of febrile inpatients, northern Tanzania, 2007-8 (n=870) Malaria (1.6%) Bacteremia (9.8%) Mycobacteremia (1.6%) Fungemia (2.9%) Brucellosis (3.5%) Leptospirosis (8.8%) Q fever (5.0%) No diagnosis (50.1%) Spotted fever group rickettsiosis (8.0%) Typhus group rickettsiosis (0.4%) Chikungunya (7.9%) Crump PLoS Neglect Trop Dis 2013; 7: e2324 Predicted environmental suitability for B. pseudomallei in East Africa Large areas of Africa are predicted to be highly suitable for Burkholderia pseudomallei East Africa is less suitable but pockets of higher suitability including northern Tanzania Northern Tanzania Increasing suitability for B. pseudomallei Limmathurotsakul Nat Microbiol. 2016;1(1). Melioidosis epidemiology in Africa Paucity of empiric data • Scattered case reports • Report from Kilifi, Kenya identified 4 bacteraemic cases from 66,000 patients who had blood cultured1 • 5.9% seroprevalence among healthy adults in Uganda2 • No reports from Tanzania 1. Limmathurotsakul Nat Microbiol. 2016;1(1). 2. Frazer J R Army Med Corps. 1982;128(3):123-30. -

Tick-Borne Disease Working Group 2020 Report to Congress

2nd Report Supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services • Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health Tick-Borne Disease Working Group 2020 Report to Congress Information and opinions in this report do not necessarily reflect the opinions of each member of the Working Group, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, or any other component of the Federal government. Table of Contents Executive Summary . .1 Chapter 4: Clinical Manifestations, Appendices . 114 Diagnosis, and Diagnostics . 28 Chapter 1: Background . 4 Appendix A. Tick-Borne Disease Congressional Action ................. 8 Chapter 5: Causes, Pathogenesis, Working Group .....................114 and Pathophysiology . 44 The Tick-Borne Disease Working Group . 8 Appendix B. Tick-Borne Disease Working Chapter 6: Treatment . 51 Group Subcommittees ...............117 Second Report: Focus and Structure . 8 Chapter 7: Clinician and Public Appendix C. Acronyms and Abbreviations 126 Chapter 2: Methods of the Education, Patient Access Working Group . .10 to Care . 59 Appendix D. 21st Century Cures Act ...128 Topic Development Briefs ............ 10 Chapter 8: Epidemiology and Appendix E. Working Group Charter. .131 Surveillance . 84 Subcommittees ..................... 10 Chapter 9: Federal Inventory . 93 Appendix F. Federal Inventory Survey . 136 Federal Inventory ....................11 Chapter 10: Public Input . 98 Appendix G. References .............149 Minority Responses ................. 13 Chapter 11: Looking Forward . .103 Chapter 3: Tick Biology, Conclusion . 112 Ecology, and Control . .14 Contributions U.S. Department of Health and Human Services James J. Berger, MS, MT(ASCP), SBB B. Kaye Hayes, MPA Working Group Members David Hughes Walker, MD (Co-Chair) Adalbeto Pérez de León, DVM, MS, PhD Leigh Ann Soltysiak, MS (Co-Chair) Kevin R. -

IAP Guidelines on Rickettsial Diseases in Children

G U I D E L I N E S IAP Guidelines on Rickettsial Diseases in Children NARENDRA RATHI, *ATUL KULKARNI AND #VIJAY Y EWALE; FOR INDIAN A CADEMY OF PEDIATRICS GUIDELINES ON RICKETTSIAL DISEASES IN CHILDREN COMMITTEE From Smile Healthcare, Rehabilitation and Research Foundation, Smile Institute of Child Health, Ramdaspeth, Akola; *Department of Pediatrics, Ashwini Medical College, Solapur; and #Dr Yewale Multispeciality Hospital for Children, Navi Mumbai; for Indian Academy of Pediatrics “Guidelines on Rickettsial Diseases in Children” Committee. Correspondence to: Dr Narendra Rathi, Consultant Pediatrician, Smile Healthcare, Rehabilitation & Research Foundation, Smile Institute of Child Health, Ramdaspeth, Akola, Maharashtra, India. [email protected]. Objective: To formulate practice guidelines on rickettsial diseases in children for pediatricians across India. Justification: Rickettsial diseases are increasingly being reported from various parts of India. Due to low index of suspicion, nonspecific clinical features in early course of disease, and absence of easily available, sensitive and specific diagnostic tests, these infections are difficult to diagnose. With timely diagnosis, therapy is easy, affordable and often successful. On the other hand, in endemic areas, where healthcare workers have high index of suspicion for these infections, there is rampant and irrational use of doxycycline as a therapeutic trial in patients of undifferentiated fevers. Thus, there is a need to formulate practice guidelines regarding rickettsial diseases in children in Indian context. Process: A committee was formed for preparing guidelines on rickettsial diseases in children in June 2016. A meeting of consultative committee was held in IAP office, Mumbai and scientific content was discussed. Methodology and results were scrutinized by all members and consensus was reached. -

Laboratory Diagnostics of Rickettsia Infections in Denmark 2008–2015

biology Article Laboratory Diagnostics of Rickettsia Infections in Denmark 2008–2015 Susanne Schjørring 1,2, Martin Tugwell Jepsen 1,3, Camilla Adler Sørensen 3,4, Palle Valentiner-Branth 5, Bjørn Kantsø 4, Randi Føns Petersen 1,4 , Ole Skovgaard 6,* and Karen A. Krogfelt 1,3,4,6,* 1 Department of Bacteria, Parasites and Fungi, Statens Serum Institut (SSI), 2300 Copenhagen, Denmark; [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (M.T.J.); [email protected] (R.F.P.) 2 European Program for Public Health Microbiology Training (EUPHEM), European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), 27180 Solnar, Sweden 3 Scandtick Innovation, Project Group, InterReg, 551 11 Jönköping, Sweden; [email protected] 4 Virus and Microbiological Special Diagnostics, Statens Serum Institut (SSI), 2300 Copenhagen, Denmark; [email protected] 5 Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Prevention, Statens Serum Institut (SSI), 2300 Copenhagen, Denmark; [email protected] 6 Department of Science and Environment, Roskilde University, 4000 Roskilde, Denmark * Correspondence: [email protected] (O.S.); [email protected] (K.A.K.) Received: 19 May 2020; Accepted: 15 June 2020; Published: 19 June 2020 Abstract: Rickettsiosis is a vector-borne disease caused by bacterial species in the genus Rickettsia. Ticks in Scandinavia are reported to be infected with Rickettsia, yet only a few Scandinavian human cases are described, and rickettsiosis is poorly understood. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of rickettsiosis in Denmark based on laboratory findings. We found that in the Danish individuals who tested positive for Rickettsia by serology, the majority (86%; 484/561) of the infections belonged to the spotted fever group. -

Tularemia – Epidemiology

This first edition of theWHO guidelines on tularaemia is the WHO GUIDELINES ON TULARAEMIA result of an international collaboration, initiated at a WHO meeting WHO GUIDELINES ON in Bath, UK in 2003. The target audience includes clinicians, laboratory personnel, public health workers, veterinarians, and any other person with an interest in zoonoses. Tularaemia Tularaemia is a bacterial zoonotic disease of the northern hemisphere. The bacterium (Francisella tularensis) is highly virulent for humans and a range of animals such as rodents, hares and rabbits. Humans can infect themselves by direct contact with infected animals, by arthropod bites, by ingestion of contaminated water or food, or by inhalation of infective aerosols. There is no human-to-human transmission. In addition to its natural occurrence, F. tularensis evokes great concern as a potential bioterrorism agent. F. tularensis subspecies tularensis is one of the most infectious pathogens known in human medicine. In order to avoid laboratory-associated infection, safety measures are needed and consequently, clinical laboratories do not generally accept specimens for culture. However, since clinical management of cases depends on early recognition, there is an urgent need for diagnostic services. The book provides background information on the disease, describes the current best practices for its diagnosis and treatment in humans, suggests measures to be taken in case of epidemics and provides guidance on how to handle F. tularensis in the laboratory. ISBN 978 92 4 154737 6 WHO EPIDEMIC AND PANDEMIC ALERT AND RESPONSE WHO Guidelines on Tularaemia EPIDEMIC AND PANDEMIC ALERT AND RESPONSE WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data WHO Guidelines on Tularaemia. -

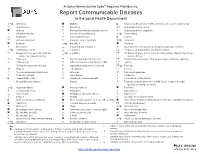

Report Communicable Diseases to the Local Health Department

Arizona Administrative Code Requires Providers to: Report Communicable Diseases to the Local Health Department *O Amebiasis Glanders O Respiratory disease in a health care institution or correctional facility Anaplasmosis Gonorrhea * Rubella (German measles) Anthrax Haemophilus influenzae, invasive disease Rubella syndrome, congenital Arboviral infection Hansen’s disease (Leprosy) *O Salmonellosis Babesiosis Hantavirus infection O Scabies Basidiobolomycosis Hemolytic uremic syndrome *O Shigellosis Botulism *O Hepatitis A Smallpox Brucellosis Hepatitis B and Hepatitis D Spotted fever rickettsiosis (e.g., Rocky Mountain spotted fever) *O Campylobacteriosis Hepatitis C Streptococcal group A infection, invasive disease Chagas infection and related disease *O Hepatitis E Streptococcal group B infection in an infant younger than 90 days of age, (American trypanosomiasis) invasive disease Chancroid HIV infection and related disease Streptococcus pneumoniae infection (pneumococcal invasive disease) Chikungunya Influenza-associated mortality in a child 1 Syphilis Chlamydia trachomatis infection Legionellosis (Legionnaires’ disease) *O Taeniasis * Cholera Leptospirosis Tetanus Coccidioidomycosis (Valley Fever) Listeriosis Toxic shock syndrome Colorado tick fever Lyme disease Trichinosis O Conjunctivitis, acute Lymphocytic choriomeningitis Tuberculosis, active disease Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease Malaria Tuberculosis latent infection in a child 5 years of age or younger (positive screening test result) *O Cryptosporidiosis -

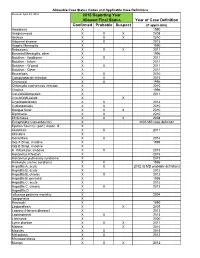

Year of Case Definition Confirmed Probable Suspect 2015 Reporting

Allowable Case Status Codes and Applicable Case Definitions Revised: April 29, 2016 2015 Reporting Year Allowed Final Status Year of Case Definition Confirmed Probable Suspect (if applicable) Amebiasis X 1990 Anaplasmosis X X X 2008 Anthrax X X X 2010 Arboviral disease X X 2015 Aseptic Meningitis X 1990 Babesiosis X X X 2011 Bacterial Meningitis, other X 1996 Botulism - foodborne X X 2011 Botulism - Infant X 2011 Botulism - Wound X X 2011 Botulism - Other X 2011 Brucellosis X X 2010 Campylobacter infection X X 2015 Chancroid X X 1996 Chlamydia trachomatis infection X 2010 Cholera X 1996 Coccidioidomycosis X 2011 Creutzfeldt-Jakob X X Cryptosporidiosis X X 2012 Cyclosporiasis X X 2010 Dengue fever X X X 2010 Diphtheria X X 2010 Ehrlichiosis X X X 2008 Encephalitis (non-arboviral) X 2005 MD case definition Epsilon Toxin (C. perf.) Assoc. Ill. X Giardiasis X X 2011 Glanders X Gonorrhea X X 2014 Grp A Strep, invasive X 1995 Grp B Strep, invasive X H. influenzae, invasive X X 2015 Hantavirus infection X 2015 Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome X 2015 Hemolytic uremic syndrome X X 1996 Hepatitis A, acute X X 2012 (& MD probable definition) Hepatitis B, acute X 2012 Hepatitis B, chronic X X 2012 Hepatitis B, perinatal X 1995 Hepatitis C, acute X 2012 Hepatitis C, chronic X X 2012 Hepatitits D X Influenza pediatric mortality X 2004 Isosporiasis X Kawasaki X 1990 Legionellosis X X 2005 Leprosy (Hansen disease) X 2013 Leptospirosis X X 2013 Listeriosis X 2000 Lyme disease X X X 2011 Malaria X X 2014 Measles X X 2013 Melioidosis X X 2012 Microsporidiosis X Mumps X X X 2012 Allowable Case Status Codes and Applicable Case Definitions Mycobacterial infection, non-TB X Neisseria meningitides, invasive X X X 2015 Novel influenza A virus infection X X X 2014 Pertussis X X 2014 Pertussis vaccine adverse rxn X Plague X X X 1996 Pneumonia in HCW X Poliomyelitis X X 2010 Psittacosis X X 2010 Q fever X X 2009 Rabies-human X 2011 Ricin toxin X Rocky Mountain spotted fever Replaced by 'Spotted fever rickettsiosis' Rubella X X X 2013 S. -

CASE REPORT MOLECULAR IDENTIFICATION of Bartonella

Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 56(4):363-365, July-August, 2014 doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652014000400017 CASE REPORT MOLECULAR IDENTIFICATION OF Bartonella henselae IN A SERONEGATIVE CAT SCRATCH DISEASE PATIENT WITH AIDS IN RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL Alexsandra R.M. FAVACHO(1), Isabelle ROGER(2), Amanda K. AKEMI(3), Adonai A. PESSOA JR.(1), Andrea G. VARON(2), Raphael GOMES(1), Daniela T. GODOY(1), Sandro PEREIRA(3) & Elba R.S. LEMOS(1) SUMMARY Bartonella henselae is associated with a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations, including cat scratch disease, endocarditis and meningoencephalitis, in immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients. We report the first molecularly confirmed case ofB. henselae infection in an AIDS patient in state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Although DNA sequence of B. henselae has been detected by polymerase chain reaction in a lymph node biopsy, acute and convalescent sera were nonreactive. KEYWORDS: Bartonella henselae; Cat scratch disease; Human immunodeficiency virus; Molecular diagnosis; Rio de Janeiro; Brazil. INTRODUCTION hospital in August 2011. Upon arrival, the patient was uncomfortable and febrile (39.5 °C) with a cluster of warm, red, enlarged, tender Bartonella species are small, fastidious, Gram-negative, rod-shaped unilateral lymph nodes on the right epitrochanteric (> 10 cm), axillar, bacteria that are associated with infections in immunocompetent supraclavicular, periauricular, and posterior cervical chain (Fig. 1). and immunocompromised patients. There are more than 22 species A discrete nonpruritic rash was noted on the torso and abdomen. The so far described in the Bartonella genus, with Bartonella henselae, patient had been scratched on the abdomen and bitten on the thumb by B. -

October 10, 2017 Special Issue • 2017 • Vol.1 • 2-11 ISSN: 1820-8620 REVISITING ANTHROP

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archivio istituzionale della ricerca - Università di Palermo October 10, 2017 Special issue • 2017 • vol.1 • 2-11 REVISITING ANTHROPOZOONOSES IN THE MEDITERRANEAN BASIN. A SINGLE-CENTRE PERSPECTIVE. A SOUTHERN ITALIAN EXPERIENCE Guadagnino G.,1 Fasciana T.,1* Caputo V.,2 Scarlata F.,1 Giammanco A.,1 Di Carlo P.1 1 Department of Sciences for Health Promotion and Mother & Child Care, University of Palermo, Italy 2 Biomedical Department of Internal and Specialist Medicine, University of Palermo, Italy *[email protected] Abstract Zoonoses, often better defined with the term anthropozoonoses, are diseases that can be transmitted to humans either by direct contact with animals or through arthropod vector intervention. Microbial interaction between humans and animals constitutes an important public health challenge, particularly in the Mediterranean basin. The main reasons this challenge is still relevant today include the phenomenon of migration, of both humans and animals, and climate change, which tend to alter the geographical distribution of zoonosis or the zoonotic agent, as well as the distribution range of potential vectors. The Mediterranean area seems to be affected by plentiful and widely distributed zoonoses, the main diseases being rickettsiosis, leishmaniasis, brucellosis, hydatid disease and viral zoonoses. The aim of this study is to revisit the prevalence and main clinical features of anthropozoonoses observed at the Department of Sciences for Health Promotion and Mother & Child Care, University of Palermo, Sicily, Southern Italy. Keywords: Anthropozoonoses, Mediterranean basin, Sicily http://pharmacologyonline.silae.it ISSN: 1820-8620 PhOL Guadagnino, et al. -

Tick-Borne Diseases

Tick-borne Diseases Presented by David Morrison Vector-borne Diseases Introduction to tick-borne illness n An organism that carries a disease and can transmit it to another organism n Ticks can be “vectors” of disease n Biting is the mechanism of transmission n Transmission is potentially the beginning of human infection Tick Species Three primary tick species Deer tick Dog tick Lone Star Tick Photo: Department of Entomology, University of Nebraska-Lincoln - Jim Kalisch, UNL Entomology Tick Species Tick 2-year life cycle Number of Deer Ticks Collected by Life Stage 900 800 700 600 500 400 300 200 100 0 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Larvae Nymph Adult Tick-borne Disease Amoeba Ehrlichiosis - Ehrlichia Anaplasmosis -Anasplasma Heartland Virus Babesiosis - Babesia Mycoplasmosis- Mycoplasma Bartonellosis- Bartonella (symptoms mimic Lyme) Bartonella quintana (Trench Powassan virus Fever) Q Fever Borrelia miyamotoi (symptoms Rocky Mountain spotted fever mimic Lyme) STARI (symptoms mimic Lyme) Boutonneuse fever Tick Paralysis Brucellosis- Brucella Tick-borne encephalitis Tickborne Relapsing Fever Chlamydophila Pneumonia Treponema Colorado tick fever Tularemia Eastern tick-borne Rickettsiosis Rickettsia phillipi Tick Species Deer tick (Ixodes scapularis) Notice the tear drop shape of the body. Tick Species Deer tick (Ixodes scapularis) ALDF Photo: Scott Bauer, USDA Lyme Disease Introduction Deer tick n Referenced over 400 years ago as an African brain parasite n Recognized in Sweden early 1908 n Identified Lyme, CT in 1975 n Symptoms mimic many other illnesses n Can attack various organ systems u Musculoskeletal u Neurologic u Cardiac Lyme Disease Introduction Deer tick n A bacterial infection caused by Borrelia burgdorferi CDC Lyme Disease Symptoms of early infection Deer tick n Erythema migrans (expanding red rash) n Fatigue, headache, stiff neck n Pain or stiffness in muscles or joints n Fever n Swollen glands Lyme Disease Early localized infection Deer tick Bull’s eye S.