Rebuilt Indigeneity: Architectural Transformations in El Alto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3. Indigeneity in the Oruro Carnival: Official Memory, Bolivian Identity and the Politics of Recognition

3. Indigeneity in the Oruro Carnival: official memory, Bolivian identity and the politics of recognition Ximena Córdova Oviedo ruro, Bolivia’s fifth city, established in the highlands at an altitude of almost 4,000 metres, nestles quietly most of the year among the mineral-rich mountains that were the reason for its foundation Oin 1606 as a Spanish colonial mining settlement. Between the months of November and March, its quiet buzz is transformed into a momentous crescendo of activity leading up to the region’s most renowned festival, the Oruro Carnival parade. Carnival is celebrated around February or March according to the Christian calendar and celebrations in Oruro include a four- day national public holiday, a street party with food and drink stalls, a variety of private and public rituals, and a dance parade made up of around 16,000 performers. An audience of 400,000 watches the parade (ACFO, 2000, p. 6), from paid seats along its route across the city, and it is broadcast nationally to millions more via television and the internet. During the festivities, orureños welcome hundreds of thousands of visitors from other cities in Bolivia and around the world, who arrive to witness and take part in the festival. Those who are not performing are watching, drinking, eating, taking part in water fights or dancing, often all at the same time. The event is highly regarded because of its inclusion since 2001 on the UNESCO list of Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, and local authorities promote it for its ability to bring the nation together. -

Formato De Proyecto De Tesis

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DEL ALTIPLANO FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES ESCUELA PROFESIONAL DE ARTE LA MÁSCARA DEL DIABLO DE PUNO, COMO ELEMENTO SIMBÓLICO, EN LA OBRA BIDIMENSIONAL TESIS PRESENTADA POR: Bach. ROSMERI CONDORI ALVAREZ PARA OPTAR EL TÍTULO PROFESIONAL DE: LICENCIADO EN ARTE: ARTES PLÁSTICAS PUNO – PERÚ 2018 UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DEL ALTIPLANO – PUNO FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES ESCUELA PROFESIONAL DE ARTE LA MÁSCARA DEL DIABLO DE PUNO, COMO ELEMENTO SIMBÓLICO, EN LA OBRA BIDIMENSIONAL TESIS PRESENTADA POR: Bach. ROSMERI CONDORI ALVAREZ PARA OPTAR EL TÍTULO PROFESIONAL DE: LICENCIADO EN ARTE: ARTES PLÁSTICAS APROBADA POR EL REVISOR CONFORMADO: PRESIDENTE: _________________________________________ D. Sc. WILBER CESAR CALSINA PONCE PRIMER MIEMBRO: _________________________________________ Lic. JOEL BENITO CASTILLO SEGUNDO MIEMBRO: _________________________________________ M. Sc. ERICH FELICIANO MORALES QUISPE DIRECTOR _________________________________________ Lic. YOVANY QUISPE VILLALTA ASESOR: _________________________________________ Mg. BENJAMÍN VELAZCO REYES Área : Artes Plásticas Tema : Producción Artística Fecha de sustentación: 10 de octubre del 2018 DEDICATORIA Quiero dedicarle este trabajo con mucho cariño. A mis padres, Julio, Matilde A mi novio Tony Yack. A todos mis hermanos. A Dios que me ha dado la vida y fortaleza para terminar este proyecto. Rosmeri, Condori Alvarez AGRADECIMIENTO ▪ A la Universidad Nacional del Altiplano de Puno, que me dio la oportunidad de formarme profesionalmente. ▪ Al Dr. Cesar Calsina y Lic. Joel Benito, a quienes me gustaría expresar mis más profundos agradecimientos, por su paciencia, tiempo, dedicación, expectativas por sus aportes para la consolidación del presenté trabajo de investigación. ▪ Mg. Oscar Bueno, por haberme brindado enseñanzas. ▪ A mi padre, por ser el apoyo más grande durante mi educación universitaria, ya que sin él no hubiera logrado mis objetivos y sueños. -

Las Danzas De Oruro En Buenos Aires: Tradición E Innovación En El Campo

Cuadernos de la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales - Universidad Nacional de Jujuy ISSN: 0327-1471 [email protected] Universidad Nacional de Jujuy Argentina Gavazzo, Natalia Las danzas de oruro en buenos aires: Tradición e innovación en el campo cultural boliviano Cuadernos de la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales - Universidad Nacional de Jujuy, núm. 31, octubre, 2006, pp. 79-105 Universidad Nacional de Jujuy Jujuy, Argentina Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=18503105 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto CUADERNOS FHyCS-UNJu, Nro. 31:79-105, Año 2006 LAS DANZAS DE ORURO EN BUENOS AIRES: TRADICIÓN E INNOVACIÓN EN EL CAMPO CULTURAL BOLIVIANO (ORURO´S DANCES IN BUENOS AIRES: TRADITION AND INNOVATION INTO THE BOLIVIAN CULTURAL FIELD) Natalia GAVAZZO * RESUMEN El presente trabajo constituye un fragmento de una investigación realizada entre 1999 y 2002 sobre la migración boliviana en Buenos Aires. La misma describía las diferencias que se dan entre la práctica de las danzas del Carnaval de Oruro en esta ciudad, y particularmente la Diablada, y la que se da en Bolivia, para poner en evidencia las disputas que los cambios producido por el proceso migratorio conllevan en el plano de las relaciones sociales. Este trabajo analizará entonces los complejos procesos de selección, reactualización e invención de formas culturales bolivianas en Buenos Aires, particularmente de esas danzas, como parte de la dinámica de relaciones propia de un campo cultural, en el que la construcción de la autoridad y de poderes constituyen elementos centrales. -

ÁNGELES Y DIABLOS EN EL CARNAVAL DE ORURO

ÁNGELES y DIABLOS EN EL CARNAVAL DE ORURO FERNANDO CAJÍAS DE LA VEGA / BOLIVIA INTRODUCCIÓN es el cuadro de la "Muerte" de Caquiaviri. Este cuadro está dividido en dos partes. En la primera, se representa OS españoles introdujeron en nuestro territorio la Muerte de! Bueno (ver Imagen 1). El "Bueno" es asistido la concepción que, después de la muerte, de la por un ángel y está recostado sobre tres almohadas; en resurrección de los muertos y de! juicio final, a cada una de ellas están pintadas, sucesivamente, tres Llos seres humanos, según su comportamiento, virtudes: la Fe, representada por una mujer con los ojos les está destinado e! cielo o e! infierno. Desde la Edad vendados, una cruz y un cáliz; la Esperanza, como una Media hasta hace pocos años, también se concebía un mujer que lleva un ancla, y la Caridad, como una mujer destino intermedio: el purgatorio. amamantando a un niño. Alrededor, en forma de escul En Hispanoamérica, como en Europa, artistas y literatos turas, están las representaciones de: la Prudencia, mujer se encargaron de presentar imágenes de cómo podrían ser leyendo con cirio; la Justicia, mujer con espada y balanza; e! cielo, e! infierno y e! purgatorio. la Fortaleza, mujer con columna (atributo de Hércules) Se han conservado numerosas obras de arte de la época y la Templanza, mujer escanciando una copa de vino. colonial en las que se representa e! cielo, paraíso o gloria, Todas las representaciones coinciden exactamente con a los ángeles y virtudes; así como el infierno o averno con los manuales de iconografía cristiana. -

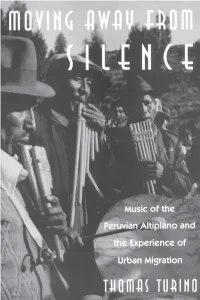

Moving Away from Silence: Music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the Experiment of Urban Migration / Thomas Turino

MOVING AWAY FROM SILENCE CHICAGO STUDIES IN ETHNOMUSICOLOGY edited by Philip V. Bohlman and Bruno Nettl EDITORIAL BOARD Margaret J. Kartomi Hiromi Lorraine Sakata Anthony Seeger Kay Kaufman Shelemay Bonnie c. Wade Thomas Turino MOVING AWAY FROM SILENCE Music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the Experience of Urban Migration THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS Chicago & London THOMAS TURlNo is associate professor of music at the University of Ulinois, Urbana. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1993 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1993 Printed in the United States ofAmerica 02 01 00 99 98 97 96 95 94 93 1 2 3 4 5 6 ISBN (cloth): 0-226-81699-0 ISBN (paper): 0-226-81700-8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Turino, Thomas. Moving away from silence: music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the experiment of urban migration / Thomas Turino. p. cm. - (Chicago studies in ethnomusicology) Discography: p. Includes bibliographical references and index. I. Folk music-Peru-Conirna (District)-History and criticism. 2. Folk music-Peru-Lirna-History and criticism. 3. Rural-urban migration-Peru. I. Title. II. Series. ML3575.P4T87 1993 761.62'688508536 dc20 92-26935 CIP MN @) The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI 239.48-1984. For Elisabeth CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction: From Conima to Lima -

Peruvian Mail

CHASQUI PERUVIAN MAIL Year 13, number 25 Cultural Bulletin of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs July, 2015 Monolithic sandeel, drawing by Wari Wilka, 1958. Wari by Monolithic sandeel, drawing CHAVÍN DE HUÁNTAR, MYTHICAL ANCIENT RUINS/ CHRONICLER GUAMAN POMA / MARIANO MELGAR´S POETRY Huántar, where at least some evidence of the use of ceramics erty claims and specialized skills organic materials were preserved and the emergence of the earliest emerged in the Early Formative thanks to the rough dry desert Andean 'classic' civilizations, period (circa 1700-1200 BC.). WHAT IS CHAVÍN Museum. Larco climate. The artifacts found in i.e. the Nazca and Mochica, was At various sites, competition for the tombs of the Paracas civiliza- called Early or Formative period resources and arable land led to tion bear some resemblance to (circa 1700-200 BC.). the creation of larger and more the Chavín stone sculptures, and The authors of this catalog ostentatious ceremonial centers. DE HUÁNTAR? also provided the first reliable agree that it is time that the ar- In the next period, the Middle dating since organic material can cheology of the Central Andes Formative period (circa 1200-800 Peter Fux* be dated physically. During the transcends preconceived notions BC.), the distinctive artistic style second half of the twentieth cen- of the Old World and in order and iconography associated with Chavin was one of the most fundamental civilizations of ancient Peru. Its imposing ceremonial center is included in tury, archaeologists preferred not to reflect this trend they use new the later findings in Chavín de to speculate on the social structure words. -

Carnival Fêtes and Feasts 1

Carnival Fêtes and Feasts 1. Rex, King of Carnival, Monarch of Merriment - Rex’s float carries the King of Carnival and his pages through the streets of New Orleans each Mardi Gras. In the early years of the New Orleans Carnival Rex’s float was redesigned each year. The current King’s float, one of Carnival’s most iconic images, has been in use for over fifty years. 2. His Majesty’s Bandwagon - From this traditional permanent float one of the Royal Bands provides lively music for Rex and for those who greet him on the parade route. One of those songs will surely be the Rex anthem: “If Ever I Cease to Love,” which has been played in every Rex parade since 1872. 3. The King’s Jesters - Even the Monarch of Merriment needs jesters in his court. Rex’s jesters dress in the traditional colors of Mardi Gras – purple, green and gold. The papier mache’ figures on the Jester float are some of the oldest in the Rex parade, and were sculpted by artists in Viareggio, Italy, a city with its own rich Carnival tradition. 4. The Boeuf Gras - The Boeuf Gras (“the fat ox”) represents one of the oldest traditions and images of Mardi Gras, symbolizing the great feast on the day before Lent begins. In the early years of the New Orleans Carnival a live Boeuf Gras, decorated with garlands, had an honored place near the front of the Rex Parade. 5. The Butterfly King - Since the earliest days of Carnival, butterflies have been popular symbolic design elements, their brief and colorful life a metaphor for the ephemeral magic of Mardi Gras itself. -

Peru's Modern Culture

A Cultural Tour Around Fabulous Peru ○○○○○○○○○○○ 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 03 Peru, General Information 05 Peru, Millennial Culture Ϭϳ Symbols that Identify Peru 11 Peru’s Pre-Columbian Art 15 Peru’s Colonial Art 21 Peru, Melting Pot of Races 25 Peru’s Dresses 27 Peru’s Folklore - Songs, Music and Dances : Coast 31 Peru’s Folklore - Songs, Music and Dances : Highlands 35 Peru’s Folklore - Songs, Music and Dances : Amazon Region 38 Peru’s Folklore - Songs, Peruvians Believers by Nature 39 Peru, Gourmet’s Paradise : Coast 44 Peru, Gourmet’s Paradise : Highlands 49 Peru, Gourmet’s Paradise: Sweets and Desserts 51 Peru, Gourmet’s Paradise: Beverages 55 Peru’s Architecture 57 Peru’s Handicrafts 66 Peru’s Modern Culture : Photography, Cinema, Theater, Music and Dance 74 Peru’s Modern Culture : Literature, Poetry, Painting, Sculpture 78 Major Festivals and Holidays 87 A Cultural Tour Around Fabulous Peru ○○○○○○○○○○○ 2 FOREWORD Peru is an extraordinary country with a rich and diverse historical background and is known for its ancient culture as cradle of civilization. The purpose of this booklet is to provide a panoramic cultural overview of Peru, the archaeological, cultural and ecological jewel of America. From the pre-Columbian cultures, the Inca splendor of Machu Picchu, its coastal desert region, the towering mountains, the verdant jungle waterways of the majestic Amazon River, to the rich artistic expressions of its people — Peru has something for everyone to enjoy. Talk to any scientists and they will tell you that Peru is one of the most exciting destinations for archaeologists today. From Caral, the oldest city in the Americas, to the mysterious Inca ruins of Machu Picchu and the Sacred Valley, to the spectacular gold, silver and jewel encrusted artifacts recently uncovered in the tombs of the Lords of Sipan, to ongoing digs along the Northern coast and highlands, Peru is an ever-expanding open-air museum. -

FIELDSTAFF Reports

WEST COAST SOUTH AMERICA SERIES Vol. XVII No. 4 (Bolivia) THE CONCEPT OF LUCK IN INDIGENOUS AND HISPANIC CULTURES by Ricliard W. Patch Bolivian beliefs about luck and destiny are clearly illustrated in the Feria de Alacilas, when people buy in miniature those objects they wish to possess in real- ity. The association of Alacitas with the Ekeko, a stylized dwarf-like figure laden with worldly goods, links present beliefs to precolonial ones. FIELDSTAFF Reports [RWP-2-'7O] WHSTCOASI LATIN AMKKKAS1 KIIS Vol. XVII No. 4 (Bolivia) THE CONCEPT OF LUCK IN INDIGENOUS AND HISPANIC CULTURES Alacitas and the Ekeko by Richard W. Patch March 1970 Do you wish to have an extra $2,083 during There is no such intriguing interpretation of Latin year? You may receive a bill of tender American Catholicism, particularly as it is mixed mised for this amount by the Feria de Alacitas with pre-Columbian beliefs, perhaps because the sending an addressed envelope, stamped with conclusions lead to ideas of predestined and ivian postage (1.40 pesos), to me at Casilla unalterable fate, indifference, and resignation to 50, La Paz, Bolivia. You will receive an Alacitas the will of an unknown. for 50 pesos (cincuenta pesos bolivianos) which I increase a thousand times in value during the Neither concept of destiny exists in pure form r to 50,000 pesos, or $2,083. The bills are apart, perhaps, from beliefs held by some individ- ted according to "the law of January 24." The uals who have become marginal in their own 083 will be yours if you believe in Alacitas and societies. -

1 Fashion in Bolivia's Cultural Economy Forthcoming, International

Fashion in Bolivia’s cultural economy Forthcoming, International Journal of Cultural Studies Kate Maclean, Birkbeck, University of London Abstract In 2016, Bolivia’s indigenous fashions gained a place on the global stage. The Brazilian ambassador to La Paz hosted a catwalk show dedicated to the luxury designers who specialise in avant garde, high quality variations on the distinctive pollera outfit – the pleated skirt, derby hat, shawl and striking jewellery that have been definitive of indigenous identity in La Paz for centuries. In the same year New York fashion week featured, for the first time, a designer from Bolivia, Eliana Paco Paredes, who is also known for her elegant and luxurious pollera designs. This article explores the development of Chola Paceña fashions and traces its social and political lineage, and place in traditions that continue to underpin Aymaran social networks and economies, whilst also becoming a symbol of their consumer power. Bolivian GDP has tripled since 2006, and this wealth has accumulated in the vast urban informal markets which are dominated by people of indigenous and mestizo descent. It is predictable that such a rise in consumption power should enable a burgeoning fashion industry. However, the femininities represented by the designs, the models and the designers place in sharp relief gendered and racialized constructions of value and how the relationship between tradition, culture and economy, has configured in scholarly work on creative labour which has been predominantly based on the experience of post-industrial cities in the global North. In August 2016, a catwalk fashion show was held in the gardens of the residence of the Brazilian Ambassador to Bolivia (Página Siete, 2016b). -

O 5 Oct 2018;:Í I\.,-•

~-e,\.ICAOti .a .1.....:' ..,1. PCRÚ ~ ~ !--"-'-JI" ;;, .. ~ ·, . ,, 1..· ,. n : .. ,.,, i<.t,,.c.,.? t ·,;i, . · .,i> /.,.,, /'. ·:. !':' :T ··'.:E .. ··..::,·.>: :,:_,.-,-:;;..-·, __ ,.,,.1·:-·,,~:~w-:• .,_r,_,-,-\,,v,,1,,J;t::' "}::i:,.f Kt!tt'K<1i'f~4{i't i .. -, ; ; :fr¡,);·;·; ;COMISION DE CULTURA YP~IRIM,9~Jº'R!:'!-I~''.Y~t.;",9 "Decenio de la Igualdad de Oportunidades para mujeres y hombres" CONGRESO - - clt'l:i- -- "Año del Diálogo y Reconciliación Nacional" REPÚBUCA DICTAMEN DE NO APROBACIÓN RECAÍDO EN EL PROYECTO DE LEY 2120/2017-CR, QUE PROPONE LA "LEY QUE CREA EL REGISTRO NACIONAL DE DANZAS FOLKLÓRICAS TÍPICAS DEL PERÚ". COMISIÓN DE CULTURA Y PATRIMONIO CULTURAL Período anual de sesiones 2018-2019 'CONGRES O O DE LA REP BLICA ÁREA DE TRÁMITE DOCUMENTAAfO , DICTAMEN 11 O 5 OCT 2018;:í I\.,-• Señor Presidente: RE C ~0.1} Frma Hora ~' Ha sido remitido para dictamen de la Comisión de Cultura y Patrimonio Cultural el Proyedo de Ley 2120/2017-CR, por el que se propone la creación de un Registro Nacional de Danzas Folklóricas Típicas del Perú. Luego del análisis y debate correspondiente, en la Sala 1 "Carlos Torres y Torres Lara" del Edificio Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre, la Comisión de Cultura y Patrimonio Cultural, en su Tercera Sesión Ordinaria del 25 de setiembre de 2018, acordó por UNANIMIDAD de los presentes la no aprobación y por consiguiente el envío al Archivo del Proyecto de Ley 2120/2017-CR, con el voto favorable de los congresistas: Edgar Ochoa Pezo; María Ramos Rosales; Víctor Albrecht Rodríguez; Karla Schaefer Cuculiza y Wilmer Aguilar Montenegro. -

My Life Story Reynaldo J. Gumucio

My Life Story Reynaldo J. Gumucio Ethnic Life Stories 2003 1 Reynaldo Gumucio José L. Gumucio, Storykeeper Ethnic Life Stories 2003 2 Reynaldo Gumucio Acknowledgement As we near the consummation of the Ethnic Life Stories Project, there is a flood of memories going back to the concept of the endeavor. The awareness was there that the project would lead to golden treasures. But I never imagined the treasures would overflow the storehouse. With every Story Teller, every Story Keeper, every visionary, every contributor, every reader, the influence and impact of the project has multiplied in riches. The growth continues to spill onward. As its outreach progresses, "boundaries" will continue to move forward into the lives of countless witnesses. Very few of us are "Native Americans." People from around the world, who came seeking freedom and a new life for themselves and their families, have built up our country and communities. We are all individuals, the product of both our genetic makeup and our environment. We are indeed a nation of diversity. Many of us are far removed from our ancestors who left behind the familiar to learn a new language, new customs, new political and social relationships. We take our status as Americans for granted. We sometimes forget to welcome the newcomer. We bypass the opportunity to ask about their origins and their own journey of courage. But, wouldn't it be sad if we all spoke the same language, ate the same food, and there was no cultural diversity. This project has left me with a tremendous debt of gratitude for so many.