Pilgrimage to the Qoyllur Rit'i and the Feast of Corpus Christi. The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3. Indigeneity in the Oruro Carnival: Official Memory, Bolivian Identity and the Politics of Recognition

3. Indigeneity in the Oruro Carnival: official memory, Bolivian identity and the politics of recognition Ximena Córdova Oviedo ruro, Bolivia’s fifth city, established in the highlands at an altitude of almost 4,000 metres, nestles quietly most of the year among the mineral-rich mountains that were the reason for its foundation Oin 1606 as a Spanish colonial mining settlement. Between the months of November and March, its quiet buzz is transformed into a momentous crescendo of activity leading up to the region’s most renowned festival, the Oruro Carnival parade. Carnival is celebrated around February or March according to the Christian calendar and celebrations in Oruro include a four- day national public holiday, a street party with food and drink stalls, a variety of private and public rituals, and a dance parade made up of around 16,000 performers. An audience of 400,000 watches the parade (ACFO, 2000, p. 6), from paid seats along its route across the city, and it is broadcast nationally to millions more via television and the internet. During the festivities, orureños welcome hundreds of thousands of visitors from other cities in Bolivia and around the world, who arrive to witness and take part in the festival. Those who are not performing are watching, drinking, eating, taking part in water fights or dancing, often all at the same time. The event is highly regarded because of its inclusion since 2001 on the UNESCO list of Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, and local authorities promote it for its ability to bring the nation together. -

Formato De Proyecto De Tesis

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DEL ALTIPLANO FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES ESCUELA PROFESIONAL DE ARTE LA MÁSCARA DEL DIABLO DE PUNO, COMO ELEMENTO SIMBÓLICO, EN LA OBRA BIDIMENSIONAL TESIS PRESENTADA POR: Bach. ROSMERI CONDORI ALVAREZ PARA OPTAR EL TÍTULO PROFESIONAL DE: LICENCIADO EN ARTE: ARTES PLÁSTICAS PUNO – PERÚ 2018 UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DEL ALTIPLANO – PUNO FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES ESCUELA PROFESIONAL DE ARTE LA MÁSCARA DEL DIABLO DE PUNO, COMO ELEMENTO SIMBÓLICO, EN LA OBRA BIDIMENSIONAL TESIS PRESENTADA POR: Bach. ROSMERI CONDORI ALVAREZ PARA OPTAR EL TÍTULO PROFESIONAL DE: LICENCIADO EN ARTE: ARTES PLÁSTICAS APROBADA POR EL REVISOR CONFORMADO: PRESIDENTE: _________________________________________ D. Sc. WILBER CESAR CALSINA PONCE PRIMER MIEMBRO: _________________________________________ Lic. JOEL BENITO CASTILLO SEGUNDO MIEMBRO: _________________________________________ M. Sc. ERICH FELICIANO MORALES QUISPE DIRECTOR _________________________________________ Lic. YOVANY QUISPE VILLALTA ASESOR: _________________________________________ Mg. BENJAMÍN VELAZCO REYES Área : Artes Plásticas Tema : Producción Artística Fecha de sustentación: 10 de octubre del 2018 DEDICATORIA Quiero dedicarle este trabajo con mucho cariño. A mis padres, Julio, Matilde A mi novio Tony Yack. A todos mis hermanos. A Dios que me ha dado la vida y fortaleza para terminar este proyecto. Rosmeri, Condori Alvarez AGRADECIMIENTO ▪ A la Universidad Nacional del Altiplano de Puno, que me dio la oportunidad de formarme profesionalmente. ▪ Al Dr. Cesar Calsina y Lic. Joel Benito, a quienes me gustaría expresar mis más profundos agradecimientos, por su paciencia, tiempo, dedicación, expectativas por sus aportes para la consolidación del presenté trabajo de investigación. ▪ Mg. Oscar Bueno, por haberme brindado enseñanzas. ▪ A mi padre, por ser el apoyo más grande durante mi educación universitaria, ya que sin él no hubiera logrado mis objetivos y sueños. -

Las Danzas De Oruro En Buenos Aires: Tradición E Innovación En El Campo

Cuadernos de la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales - Universidad Nacional de Jujuy ISSN: 0327-1471 [email protected] Universidad Nacional de Jujuy Argentina Gavazzo, Natalia Las danzas de oruro en buenos aires: Tradición e innovación en el campo cultural boliviano Cuadernos de la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales - Universidad Nacional de Jujuy, núm. 31, octubre, 2006, pp. 79-105 Universidad Nacional de Jujuy Jujuy, Argentina Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=18503105 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto CUADERNOS FHyCS-UNJu, Nro. 31:79-105, Año 2006 LAS DANZAS DE ORURO EN BUENOS AIRES: TRADICIÓN E INNOVACIÓN EN EL CAMPO CULTURAL BOLIVIANO (ORURO´S DANCES IN BUENOS AIRES: TRADITION AND INNOVATION INTO THE BOLIVIAN CULTURAL FIELD) Natalia GAVAZZO * RESUMEN El presente trabajo constituye un fragmento de una investigación realizada entre 1999 y 2002 sobre la migración boliviana en Buenos Aires. La misma describía las diferencias que se dan entre la práctica de las danzas del Carnaval de Oruro en esta ciudad, y particularmente la Diablada, y la que se da en Bolivia, para poner en evidencia las disputas que los cambios producido por el proceso migratorio conllevan en el plano de las relaciones sociales. Este trabajo analizará entonces los complejos procesos de selección, reactualización e invención de formas culturales bolivianas en Buenos Aires, particularmente de esas danzas, como parte de la dinámica de relaciones propia de un campo cultural, en el que la construcción de la autoridad y de poderes constituyen elementos centrales. -

Cocktails Beer

Cocktails Aperitif Chinese Lantern 19 Aperol, St. Germain, cava, mandarin, plum bitters I’m Your Venus 19 Kleos Mastiha, Giffard Banane du Brésil, lemon, lime, egg white Spirit-subtle Comfortably Numb 20 Vanilla vodka, lychee liqueur, honey, lime, Thai chili, Sichuan peppercorn Magic Lamp 21 Jasmine tea-infused Maestro Dobel Tequila, Braulio, Lucano, St. Agrestis, grapefruit, lime, honey Pink Panda 22 Michter’s US*1 Rye, Campari, L’Orgeat, pineapple, lime, pandan Vermilion Bird 20 Five-spiced rum, ginger beer, lemon, butterfly pea flower Spirit-forward Kunlun Cocktail 22 Greenhook American Dry & Old Tom Gins, Arcane Whiskey, chrysanthemum Su Song 20 Diplomatico Reserva Exclusiva Rum, Fernet Vittone, crème de mûre, Chinese licorice tincture Ancient Old-Fashioned 21 Sesame-washed Bourbon, Hennessy Black, Benedictine, molé bitters HUTONG Lucky Dragon 22 Scotch, amontillado sherry, Ancho Reyes verde, nocino, Angostura bitters, five-spice tincture Non-Alcoholic Soolong Sucker 13 Salted oolong ice, mystic mango lemonade Butterfly Rickey 13 Butterfly pea flower tea, lemon, honey, plum bitters Beer Tsingtao 8 Premium Lager, China | 11.2oz Southern Tier 9 Live Pale Ale, New York | 12oz Ithaca Beer Co. 10 Flower Power IPA, New York | 12oz Ommegang 11 Hennepin, New York | 12oz Greenport Harbor 10 Black Duck Porter, New York | 12oz Grimm 27 Cherry Rebus, New York | 16.9oz Athletic 9 Upside Dawn, Non-Alcoholic, Connecticut | 12oz By the glass Champagne & Sparkling Champagne nv 27 Gonet-Médeville, 1er ‘Tradition’, Champagne, France | O Crémant de Bourgogne -

El Ball De Diables Té L'orígen En Un Entemés on Es Representa La Lluita Entre El Bé I El

Concomitàncies entre els balls de diables catalans i les «diabladas» d’Amèrica del Sud Jordi Rius i Mercadé El ball de diables, un ball parlat. El Ball de Diables té l’origen en un entremès on es representa la lluita entre el bé i el mal. L’Arcàngel Sant Miquel i els seus àngels s’enfronten a les forces malignes representades per Llucifer i els seus diables. El folklorista Joan Amades data la primera representació d’aquest entremès l’any 1150, en motiu de les noces del Comte Ramon Berenguer IV amb la princesa Peronella, filla del rei Ramir el Monjo d’Aragó. En el segle XIV s’instaura una nova festa, el Corpus Christi. Sorgeix una processó al carrer on s’aglutinen diversos elements (teatrals, rituals, simbòlics...) que donen peu a un extraordinari espectacle itinerant integrat per danses paganes i religioses, entremesos, elements de bestiari i personatges bíblics. A les viles de Barcelona, Lleida, Cervera, València i Tarragona descobrim que a les seves processons de Corpus del segle XV surt al carrer l’entremès de la lluita de Sant Miquel amb Llucifer. També tenim notícies d’aquest entremès fora de l’àmbit dels Països Catalans, com a Saragossa o a Múrcia. Però cal dir que són els països de parla catalana qui conserven aquella teatralitat medieval com a base sòlida que es perpetua al llarg dels segles, conservant i evolucionant meravelles úniques de teatralitat medieval com el Misteri d’Elx, el Cant de la Sibil·la mallorquí, o els diversos seguicis populars del Principat com ara el de Berga, Tarragona o Vilafranca. -

ÁNGELES Y DIABLOS EN EL CARNAVAL DE ORURO

ÁNGELES y DIABLOS EN EL CARNAVAL DE ORURO FERNANDO CAJÍAS DE LA VEGA / BOLIVIA INTRODUCCIÓN es el cuadro de la "Muerte" de Caquiaviri. Este cuadro está dividido en dos partes. En la primera, se representa OS españoles introdujeron en nuestro territorio la Muerte de! Bueno (ver Imagen 1). El "Bueno" es asistido la concepción que, después de la muerte, de la por un ángel y está recostado sobre tres almohadas; en resurrección de los muertos y de! juicio final, a cada una de ellas están pintadas, sucesivamente, tres Llos seres humanos, según su comportamiento, virtudes: la Fe, representada por una mujer con los ojos les está destinado e! cielo o e! infierno. Desde la Edad vendados, una cruz y un cáliz; la Esperanza, como una Media hasta hace pocos años, también se concebía un mujer que lleva un ancla, y la Caridad, como una mujer destino intermedio: el purgatorio. amamantando a un niño. Alrededor, en forma de escul En Hispanoamérica, como en Europa, artistas y literatos turas, están las representaciones de: la Prudencia, mujer se encargaron de presentar imágenes de cómo podrían ser leyendo con cirio; la Justicia, mujer con espada y balanza; e! cielo, e! infierno y e! purgatorio. la Fortaleza, mujer con columna (atributo de Hércules) Se han conservado numerosas obras de arte de la época y la Templanza, mujer escanciando una copa de vino. colonial en las que se representa e! cielo, paraíso o gloria, Todas las representaciones coinciden exactamente con a los ángeles y virtudes; así como el infierno o averno con los manuales de iconografía cristiana. -

Les Cases De La Festa a Barcelona

06 03 06 06 QuadernsQuadernsQuadernsQuaderns deldel deldel QuadernsQuaderns ConsellConsellConsellConsell dede dede 6 coordinacióCoordinaciócoordinacióCoordinació del Conselldel Consell pedagògicaPedagògicapedagògicaPedagògica de Coordinacióde Coordinació PedagògicaPedagògica Les Cases de la Festa a Barcelona: imatgeria, Les Cases de la Festa a Barcelona Festa de la Cases Les foc, dansa i música Les Cases de la Festa a Barcelona: imatgeria, foc, dansa i música Jordi Puig i Martín, Jordi Quintana i Albalat 2 Presentació els confereix sentiment, i sentit. (...) Ara, doncs, si no és a través de l’escola (...), la transmissió de la cultura po- Barcelona és una ciutat molt rica pel que fa al seu patri- pulacorre el risc de caure en l’oblit...” (Soler, 2011). moni de cultura popular i tradicional. I això, que d’en- trada és un motiu de satisfacció, representa també per El nostre objectiu amb aquest document ha estat a la ciutadania i per a les seves institucions una gran elaborar una eina útil. Com veureu, és un recull d’in- responsabilitat, de cara a mantenir viva aquesta expres- formacions i de coneixements, articulats seguint l’es- sió heretada i transformada de generació en generació. I quema de les visites escolars a les Cases de la Festa. és en aquest sentit que cal felicitar-nos per l’impuls, per Nosaltres voldríem que servís tant per a les persones part de l’Ajuntament de Barcelona, de la Xarxa de Cases que han de dur a terme les activitats, perquè puguin de la Festa, una iniciativa pionera al nostre país en la preparar-les amb més rigor pel que fa als continguts, línia de promoure el coneixement i fomentar la parti- com —i sobretot— per als mestres, perquè puguin pre- cipació en tot allò relacionat amb la cultura popular i parar millor les sessions prèvies i posteriors a l’aula. -

La Transformación Del Mito De Wari En Las Fiestas Mestizas De

Mitologías hoy 2 (verano 2011) 61‐72 Max Meier 61 ISSN: 2014‐1130 La transformación del mito de Wari en las fiestas mestizas de Oruro y Puno en el Altiplano peruano‐boliviano: la Diablada y la construcción de nuevas identidades regionales MAX MEIER Para Manuel Una de las formas de expresión y comunicación estética, no escritas, más llamativa de los habitantes de toda la sierra andina son las fiestas. Este ensayo se centrará en dos fiestas del ambiente urbano: el Carnaval de Oruro en Bolivia y la Fiesta de la Virgen de la Candelaria en Puno, Perú. Ambas fiestas están vinculadas a leyendas o mitos. Muchos de ellos han sido transformados o incluso inventados según los intereses de algún sector social, por lo general poderoso y dominante en el terreno político y económico local. Oruro tiene alrededor de 220.000 habitantes y Puno unos 125.000. Ambas urbes son capitales de departamentos del mismo nombre, encontrándose las dos en la zona altiplánica a más de 3.700 msnm. Las fiestas son el evento cultural dominante en ambas regiones, y quien no participa activamente en ellas –y en un lugar prominente– tendrá grandes dificultades de mantener o de ascender a una posición de liderazgo social o político local. El análisis de la evolución histórica y actual de las fiestas es una de las principales bases para comprender las culturas andinas tanto las indígenas como las mestizas y, por ende, su posicionamiento frente al mundo. Son culturas que no se expresan en primer lugar a través de la escritura, y que no transmiten sus valores, su saber y su historia necesariamente en libros o academias y que –ya desde antes de la conquista española– han ido procesando influencias y aportes de otras culturas. -

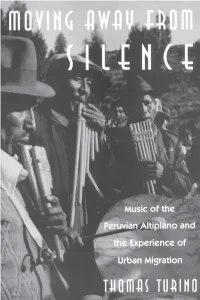

Moving Away from Silence: Music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the Experiment of Urban Migration / Thomas Turino

MOVING AWAY FROM SILENCE CHICAGO STUDIES IN ETHNOMUSICOLOGY edited by Philip V. Bohlman and Bruno Nettl EDITORIAL BOARD Margaret J. Kartomi Hiromi Lorraine Sakata Anthony Seeger Kay Kaufman Shelemay Bonnie c. Wade Thomas Turino MOVING AWAY FROM SILENCE Music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the Experience of Urban Migration THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS Chicago & London THOMAS TURlNo is associate professor of music at the University of Ulinois, Urbana. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1993 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1993 Printed in the United States ofAmerica 02 01 00 99 98 97 96 95 94 93 1 2 3 4 5 6 ISBN (cloth): 0-226-81699-0 ISBN (paper): 0-226-81700-8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Turino, Thomas. Moving away from silence: music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the experiment of urban migration / Thomas Turino. p. cm. - (Chicago studies in ethnomusicology) Discography: p. Includes bibliographical references and index. I. Folk music-Peru-Conirna (District)-History and criticism. 2. Folk music-Peru-Lirna-History and criticism. 3. Rural-urban migration-Peru. I. Title. II. Series. ML3575.P4T87 1993 761.62'688508536 dc20 92-26935 CIP MN @) The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI 239.48-1984. For Elisabeth CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction: From Conima to Lima -

Rebuilt Indigeneity: Architectural Transformations in El Alto

ISSN 2624-9081 • DOI 10.26034/roadsides-202000402 Rebuilt Indigeneity: Architectural Transformations in El Alto Juliane Müller The colorful façades are best seen from the Blue Line of Mi Teleférico, the aerial cable- car network that has been the backbone of urban transport in the metropolitan area of La Paz and El Alto since 2014. From above, the multistory buildings internationally known as Neo-Andean Architecture can be admired in their distinctive splendor, rising over the sober and nearly treeless landscape of El Alto, Bolivia’s youngest and Latin America’s foremost indigenous city. Populated through rural–urban migration since the early twentieth century, but only founded as an independent municipality in 1985, El Alto has been devoid of monumental sites. These buildings and the new cable-car system are the first structures with sufficient aesthetic and symbolic qualities to evoke positive reactions from residents and tourists alike. In this essay, I approach them through an architectural lens. The cable-car infrastructure is not primarily conceptualized as a network but rather analyzed through its historically informed symbolism and as a series of distinctive material forms with specific social and political effects (Seewang 2013). I show that the Neo-Andean Architecture and the cable-car station buildings not only reshape the city’s landscape but are themselves materializations of an urban understanding of indigeneity that embraces infrastructural development and accommodates social difference. collection no. 004 • Architecture and/as Infrastructure Roadsides Rebuilt Indigeneity 09 Neo-Andean Architecture Regardless of its broad denomination, Neo-Andean Architecture originated in El Alto and is associated with a single name, the Aymara Freddy Mamani. -

Peruvian Mail

CHASQUI PERUVIAN MAIL Year 13, number 25 Cultural Bulletin of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs July, 2015 Monolithic sandeel, drawing by Wari Wilka, 1958. Wari by Monolithic sandeel, drawing CHAVÍN DE HUÁNTAR, MYTHICAL ANCIENT RUINS/ CHRONICLER GUAMAN POMA / MARIANO MELGAR´S POETRY Huántar, where at least some evidence of the use of ceramics erty claims and specialized skills organic materials were preserved and the emergence of the earliest emerged in the Early Formative thanks to the rough dry desert Andean 'classic' civilizations, period (circa 1700-1200 BC.). WHAT IS CHAVÍN Museum. Larco climate. The artifacts found in i.e. the Nazca and Mochica, was At various sites, competition for the tombs of the Paracas civiliza- called Early or Formative period resources and arable land led to tion bear some resemblance to (circa 1700-200 BC.). the creation of larger and more the Chavín stone sculptures, and The authors of this catalog ostentatious ceremonial centers. DE HUÁNTAR? also provided the first reliable agree that it is time that the ar- In the next period, the Middle dating since organic material can cheology of the Central Andes Formative period (circa 1200-800 Peter Fux* be dated physically. During the transcends preconceived notions BC.), the distinctive artistic style second half of the twentieth cen- of the Old World and in order and iconography associated with Chavin was one of the most fundamental civilizations of ancient Peru. Its imposing ceremonial center is included in tury, archaeologists preferred not to reflect this trend they use new the later findings in Chavín de to speculate on the social structure words. -

Carnival Fêtes and Feasts 1

Carnival Fêtes and Feasts 1. Rex, King of Carnival, Monarch of Merriment - Rex’s float carries the King of Carnival and his pages through the streets of New Orleans each Mardi Gras. In the early years of the New Orleans Carnival Rex’s float was redesigned each year. The current King’s float, one of Carnival’s most iconic images, has been in use for over fifty years. 2. His Majesty’s Bandwagon - From this traditional permanent float one of the Royal Bands provides lively music for Rex and for those who greet him on the parade route. One of those songs will surely be the Rex anthem: “If Ever I Cease to Love,” which has been played in every Rex parade since 1872. 3. The King’s Jesters - Even the Monarch of Merriment needs jesters in his court. Rex’s jesters dress in the traditional colors of Mardi Gras – purple, green and gold. The papier mache’ figures on the Jester float are some of the oldest in the Rex parade, and were sculpted by artists in Viareggio, Italy, a city with its own rich Carnival tradition. 4. The Boeuf Gras - The Boeuf Gras (“the fat ox”) represents one of the oldest traditions and images of Mardi Gras, symbolizing the great feast on the day before Lent begins. In the early years of the New Orleans Carnival a live Boeuf Gras, decorated with garlands, had an honored place near the front of the Rex Parade. 5. The Butterfly King - Since the earliest days of Carnival, butterflies have been popular symbolic design elements, their brief and colorful life a metaphor for the ephemeral magic of Mardi Gras itself.