The Hands That Sew the Sequins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Percy Savage Interviewed by Linda Sandino: Full Transcript of the Interview

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH AN ORAL HISTORY OF BRITISH FASHION Percy Savage Interviewed by Linda Sandino C1046/09 IMPORTANT Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB United Kingdom +44 [0]20 7412 7404 [email protected] Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators. THE NATIONAL LIFE STORY COLLECTION INTERVIEW SUMMARY SHEET Ref. No.: C1046/09 Playback No.: F15198-99; F15388-90; F15531-35; F15591-92 Collection title: An Oral History of British Fashion Interviewee’s surname: Savage Title: Mr Interviewee’s forenames: Percy Sex: Occupation: Date of birth: 12.10.1926 Mother’s occupation: Father’s occupation: Date(s) of recording: 04.06.2004; 11.06.2004; 02.07.2004; 09.07.2004; 16.07.2004 Location of interview: Name of interviewer: Linda Sandino Type of recorder: Marantz Total no. of tapes: 12 Type of tape: C60 Mono or stereo: stereo Speed: Noise reduction: Original or copy: original Additional material: Copyright/Clearance: Interview is open. Copyright of BL Interviewer’s comments: Percy Savage Page 1 C1046/09 Tape 1 Side A (part 1) Tape 1 Side A [part 1] .....to plug it in? No we don’t. Not unless something goes wrong. [inaudible] see well enough, because I can put the [inaudible] light on, if you like? Yes, no, lovely, lovely, thank you. -

Oddo Forum Lyon, January 7&8, 2016

Oddo Forum Lyon, January 7&8, 2016 Contents V Interparfums V Stock market V 2015 highlights V 2015 & 2016 highlights by brand V 2015 & 2016 results 2 Interparfums ___ 3 Interparfums V An independent "pure player" in the perfume and cosmetics industry V A creator, manufacturer and distributor of prestige perfumes based on a portfolio of international luxury brands 44 Brand portfolio V Brand licenses under exclusive worldwide agreements ° S.T. Dupont (1997 2016) ° Paul Smith (1998 2017) ° Van Cleef & Arpels (2007 2018) ° Montblanc (2010 2020 2025) ° Jimmy Choo (2010 2021) ° Boucheron (2011 2025) ° Balmain (2012 2024) ° Repetto (2012 2025) ° Karl Lagerfeld (2012 2032) ° Coach (2016 2026) V Proprietary brands ° Lanvin (perfumes) (2007) ° Rochas (perfumes & fashion) (2015) 5 License agreements V The license grants a right to use the brand V Over a long-term period (10 years, 15 years, 20 years or more) V In exchange for meeting qualitative obligations: ° Distribution network ° Number of launches ° Nature of advertising expenses… V and quantitative obligations ° Royalties (procedures for calculation, amount and minimum commitment) ° Advertising expenses (budgets, amount and minimum commitment) 6 The brands . A bold luxury fashion brand . Collections with distinctive style for an elegant and glamorous woman . 17 brand name stores . A 12-year license agreement executed in 2012 . One of the world’s most prestigious jewelers . A sensual and feminine universe . Boucheron creations render women resplendent . A 15-year license agreement executed in 2010 7 The brands . A brand created in 1941 with a rich and authentic American heritage . A global leader in premium handbags and lifestyle accessories . 3,000 doors worldwide . -

Jeanne Lanvin

JEANNE LANVIN A 01long history of success: the If one glances behind the imposing façade of Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, 22, in Paris, Lanvin fashion house is the oldest one will see a world full of history. For this is the Lanvin headquarters, the oldest couture in the world. The first creations house in the world. Founded by Jeanne Lanvin, who at the outset of her career could not by the later haute couture salon even afford to buy fabric for her creations. were simple clothes for children. Lanvin’s first contact with fashion came early in life—admittedly less out of creative passion than economic hardship. In order to help support her six younger siblings, Lanvin, then only fifteen, took a job with a tailor in the suburbs of Paris. In 1890, at twenty-seven, Lanvin took the daring leap into independence, though on a modest scale. Not far from the splendid head office of today, she rented two rooms in which, for lack of fabric, she at first made only hats. Since the severe children’s fashions of the turn of the century did not appeal to her, she tailored the clothing for her young daughter Marguerite herself: tunic dresses designed for easy movement (without tight corsets or starched collars) in colorful patterned cotton fabrics, generally adorned with elaborate smocking. The gentle Marguerite, later known as Marie-Blanche, was to become the Salon Lanvin’s first model. When walking JEANNE LANVIN on the street, other mothers asked Lanvin and her daughter from where the colorful loose dresses came. -

The Jeanne Lanvin Impressionist Art Collection

CONTACT Capucine Milliot (Paris) + 331 40 76 85 88 [email protected] Alexandra Kindermann (London) + 44 207 389 2289 [email protected] Milena Sales (New York) +1 212 636 2676 [email protected] Kate Malin (Hong Kong) + 852 2978 9966 [email protected] The Jeanne Lanvin Impressionist Art Collection EXCEPTIONAL IMPRESSIONIST PAINTINGS FROM THE JEANNE LANVIN COLLECTION AND THE POLIGNAC KERJEAN AND THE FORTERESSE DE POLIGNAC FOUNDATIONS . 1st December 2008 Pierre Auguste Renoir Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) Femme nue au canapé La Coiffure, 1922 Estimate: €800,000-1,200,000 Estimate: €1,000,000-1,500,000 Paris – Christie’s Impressionist and Modern Art department is delighted to announce the sale of the Exceptional Collection of Jeanne Lanvin and the Polignac Foundations. This Collection pays homage to the eye of a woman who personifies Parisian elegance, Jeanne Lanvin, continuing with her daughter Marie-Blanche de Polignac and then on to a dynasty of patrons and lovers of art, the Polignac family. The benchmark collection of Impressionist paintings is estimated to realize around 20 million Euros. It is the most significant collection of Impressionist Art to be offered on the market in France. Thirty-one works by Pierre Bonnard, Eugène Boudin, Georges Braque, Mary Cassatt, Edgar Degas, Jean-Louis Forain, Roger de la Fresnay, Pablo Picasso, Camille Pissarro, Jean-François Raffaelli, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Edouard Vuillard are included in this auction. A portion of the proceeds from the sale will go toward the two Polignac Foundations. According to Anika Guntrum, Head of Department in Paris “This collection carries the imprint of the Lanvin soule, and is a testimony to the way in which Jeanne Lanvin, with her acute business acumen and refined taste, built not only an empire but an eclectic yet perfectly harmonious art collection. -

Fragonard Magazine N°9 - 2021 a Year of PUBLICATION DIRECTOR and CHIEF EDITOR New Charlotte Urbain Assisted By, Beginnings Joséphine Pichard Et Ilona Dubois !

MAGAZINE 2021 9 ENGLISH EDITORIAL STAFF directed by, 2021, Table of Contents Agnès Costa Fragonard magazine n°9 - 2021 a year of PUBLICATION DIRECTOR AND CHIEF EDITOR new Charlotte Urbain assisted by, beginnings Joséphine Pichard et Ilona Dubois ! ART DIRECTOR Claudie Dubost assisted by, Maria Zak BREATHE SHARE P04 Passion flower P82 Audrey’s little house in Picardy AUTHORS Louise Andrier P10 News P92 Passion on the plate recipes Jean Huèges P14 Laura Daniel, a 100%-connected by Jacques Chibois Joséphine Pichard new talent! P96 Jean Flores & Théâtre de Grasse P16 Les Fleurs du Parfumeur Charlotte Urbain 2020 will remain etched in our minds as the in which we all take more care of our planet, CELEBRATE CONTRIBUTORS year that upturned our lives. Yet, even though our behavior and our fellow men and women. MEET P98 Ten years of acquisitions at the Céline Principiano, Carole Blumenfeld we’ve all suffered from the pandemic, it has And especially, let’s pledge to turn those words P22 Musée Jean-Honoré Fragonard leading the way Eva Lorenzini taught us how to adapt and behave differently. into actions! P106 A-Z of a Centenary P24 Gérard-Noel Delansay, Clément Trouche As many of you know, Maison Fragonard is a Although uncertainty remains as to the Homage to Jean-François Costa a familly affair small, 100% family-owned French house. We reopening of social venues, and we continue P114 Provence lifestyle PHOTOGRAPHERS enjoy a very close relationship with our teams to feel the way in terms of what tomorrow will in the age of Fragonard ESCAPE Olivier Capp and customers alike, so we deeply appreciate bring, we are over the moon to bring you these P118 The art of wearing perfume P26 Viva România! Eva Lorenzini your loyalty. -

Fragrance List Print

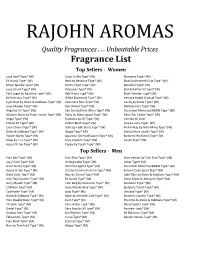

Quality Fragrances . Unbeatable Prices Fragrance List Top Sellers - Women Love Spell Type* (W) Gucci Guilty Type* (W) Romance Type* (W) Ed Hardy Type*RAJOHN (W) Heat by Beyonce Type* (W)AROMASBlack by Kenneth Cole Type* (W) Moon Sparkle Type* (W) Jimmy Choo Type* (W) Beautiful Type* (W) Love Struck Type* (W) Pleasures Type* (W) Bombshell by VS Type* (W) Pink Sugar by Aquolina Type* (W) Reb'l Fleur Type* (W) Black Woman Type* (W) Be Delicious Type* (W) White Diamonds Type* (W) Versace Bright Crystsal Type* (W) Light Blue by Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Cashmere Mist Type* (W) Candy by Prada Type* (W) Issey Miyake Type* (W) Butt Naked Type* (W) Michael Kors Type* (W) Angel by VS Type* (W) Can Can by Paris Hilton Type* (W) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type* (W) Modern Muse by Estee Lauder Type* (W) Daisy by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Miss Dior Cherie Type* (W) Angel Type* (W) Euphoria by CK Type* (W) Lick Me All Over Chanel #5 Type* (W) Amber Blush Type* (W) Viva La Juicy Type* (W) Coco Chanel Type* (W) Halle by Halle Berry Type* (W) Pink Friday by Nicki Minaj Type* (W) Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Happy Type* (W) Dot by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Flower Bomb Type* (W) Japanese Cherry Blossom Type* (W) Burberry Weekend Type* (W) Glow by J. Lo Type* (W) Juicy Couture Type* (W) Coach Type* (W) Acqua Di Gio Type* (W) Poppy by Coach Type* (W) Top Sellers - Men Polo Red Type* (M) Polo Blue Type* (M) Grey Vetiver by Tom Ford Type* (M) Jay-Z Gold Type* (M) Unforgivable Type* (M) Usher Type* (M) Gucci Guilty Type* (M) Chrome Legend Type* (M) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type* -

The 100 Most Renowned Luxury Brands and Their Presence in Europe's Metropolitan Centres

Glitter and glamour shining brightly The 100 most renowned luxury brands and their presence in Europe’s metropolitan centres Advance • Luxury shopping streets Europe • July 2011 2 Worldwide luxury market has emerged stronger from the financial crisis The global market for luxury goods has emerged from the financial uses images of diligent craftsmen and companies seek to add crafts crisis significantly faster than expected. The likes of Burberry, Gucci firms with long traditions to their portfolios. At the same time, the Group, Hermès, LVMH, Polo Ralph Lauren, Prada and Richemont east-bound shift of manufacturing activities, which was in full swing have recently reported double-digit sales growth or even record an- before the financial crisis, has slowed down significantly. nual sales, which has also reflected favourably on their share prices. Companies’ own store networks have played a significant role in all Rising requirements in the areas of marketing and logistics these success stories, with their retail operations typically growing March saw the launch of Mr Porter, the new men’s fashion portal of ahead of their other divisions. Most recently business has mainly Net-a-Porter, the world’s leading e-commerce seller of luxury goods. been driven by Asia. With the exception of Japan, this is where the Yoox most recently reported a continuing rise in its sales figures. All luxury brands have recorded the highest growth rates. In particular major luxury labels have considerably expanded the online shopping luxury fashion makers have greatly benefited from the booming Chi- offerings on their websites and feature them prominently in their nese market. -

Inter Parfums Sa

positive underlying growthtrends contents letter to our shareholders 03 operating highlights and key figures 07 the stockmarket and investor relations 09 2007 milestones and 2008 outlook 13 activity and philosophy 15 the products 17 the distribution network 39 sustainable development 41 corporate governance 49 consolidated financials 61 shareholder information 81 auditors and certificates 91 2007 In 2007, the Group achieved In response to stronger than Van Cleef & Arpels fragrances, another year of sustained expected year-end growth, in the initial phase of being growth with consolidated consolidated sales for 2007 integrated in the Group's portfolio, sales of €242.1 million, up 12% marginally exceeded guidance achieved encouraging sales at current exchange rates and issued in the fall. of close to €12 million. 15% at constant exchange rates. Despite the absence of major The first fragrance line launched launches, market shares achieved under the Roxy brand contributed by Burberry fragrances over the sales of €6.6 million in the period years were reinforced by gains and met with a mixed response from its historic lines: on this from the market. basis, sales exceeded the €150 Western Europe (excluding France) million benchmark for the first time. remained the Group's largest Lanvin fragrances met internal market (more than 30% of total targets through sustained growth sales), by the Eclat d’Arpège line (+16% Continued success of Burberry in 2007, +17% in 2006), the Group’s fragrances in the United States top-selling fragrance, that offset fueled strong growth in volume the mixed performance of the in North America, Rumeur line launched in 2006. -

Fashion's Autumn/Winter 2014 Ad Campaigns | Financial Times

04/01/2020, 10:22 Page 1 of 1 Luxury goods Add to myFT Fashion’s autumn/winter 2014 ad campaigns A deconstruction of the industry’s ads for the season reveals a sombre economic mood Share Save David Hayes AUGUST 8 2014 Hemlines may once have been a cute way of monitoring the state of the economy – rather aptly, they are all over the place these days – but nothing gives a snapshot of global hard-currency health better than a flick through the September issues of the world’s glossiest fashion magazines. Landing on newsstands with a reassuringly weighty thud early this month, the current edition of US Vogue has more advertising than any other American fashion or lifestyle magazine, with a whopping 631 ad pages. Yet it is still down 4.5 per cent on last year’s Lady Gaga extravaganza of 665 pages – which in turn was down on the magazine’s peak of 727 pages of ads in 2007. The luxury sector may not have turned an economic corner – yet. And in fashion terms the mood is not exactly upbeat, either: think brown and black set against brutalist concrete architecture (Prada); corseted women hanging around in a drab hotel suite (Dior); and models trapped in a surrealist crazy golf course from hell, wearing equally disturbing knitwear (Kenzo). Yes, advertising matters, not only as a barometer of the spending trends of the fashion world, but also as a tone-setting exercise. The following images are how fashion should look this autumn/winter, straight from the designer’s eye, so take note. -

Graphic Content

BIG IN BEIJING DIANE VON FURSTENBERG FETED WITH EXHIBIT IN CHINA. STYLE, PAGE S2 WWDTUESDAY, APRIL 5, 2011 ■ WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY ■ $3.00 ZEROING IN Puig Said In Talks Over Gaultier Stake founded in 1982, and remain at the By MILES SOCHA creative helm. As reported, Hermès said Friday PARIS — As Parisian as the Eiffel it had initiated discussions to sell its Tower, Jean Paul Gaultier might soon shares in Gaultier, without identify- become a Spanish-controlled company. ing the potential buyers. The maker According to market sources, of Birkin bags and silk scarves de- Puig — the Barcelona-based parent clined all comment on Monday, as did of Carolina Herrera, Nina Ricci and a spokeswoman for Gaultier. Paco Rabanne — has entered into ex- Puig offi cials could not be reached clusive negotiations to acquire the 45 for comment. percent stake in Gaultier owned by A deal with Puig — a family-owned Hermès International. company that has recently been gain- It is understood Puig will also pur- ing traction with Ricci and expand- chase some shares from Gaultier him- ing Herrera and has a reputation for self, which would give the Spanish being respectful of creative talents beauty giant majority ownership of —would offer a new lease on life for a landmark French house — and in- Gaultier, a designer whose licensing- stantly make it a bigger player in the driven fashion house has struggled to fashion world. thrive in the shadow of fashion giants Gaultier, 58, is expected to retain like Chanel, Dior and Gucci. a signifi cant stake in the company he SEE PAGE 6 IN WWD TODAY Armani Eyes U.S. -

The Impact of World War II on Women's Fashion in the United States and Britain

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 12-2011 The impact of World War II on women's fashion in the United States and Britain Meghann Mason University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Cultural History Commons, European History Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Industrial and Product Design Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation Mason, Meghann, "The impact of World War II on women's fashion in the United States and Britain" (2011). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 1390. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/3290388 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IMPACT OF WORLD WAR II ON WOMEN’S FASHION IN THE UNITED STATES AND BRITAIN By Meghann Mason A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements -

The State of Fashion 2019 the State of Fashion 2019 the State of Fashion

The State of Fashion 2019 The State of Fashion 2019 The State of Fashion 2 The State of Fashion 2019 The State of Fashion 2019 Contents Executive Summary 10 Executive Summary Executive Industry Outlook 12 Global Economy 18—37 Trend 1: Caution Ahead 19 Executive Interview: Joann Cheng 22 Trend 2: Indian Ascent 24 Executive Interview: Darshan Mehta 28 Global Economy Trend 3: Trade 2.0 31 Global Value Chains in Apparel: The New China Effect 34 Consumer Shifts 38—69 Trend 4: End of Ownership 39 Executive Interview: Jennifer Hyman 42 Consumer Shifts Trend 5: Getting Woke 45 Executive Interview: Cédric Charbit 48 Trend 6: Now or Never 51 Executive Interview: Jeff Gennette 54 Digital Innovation Made Simple 58 Trend 7: Radical Transparency 60 Dealing with the Trust Deficit 62 Fashion System Fashion Fashion System 70—91 Trend 8: Self-Disrupt 71 The Explosion of Small 74 Trend 9: Digital Landgrab 77 Executive Interview: Nick Beighton 80 Trend 10: On Demand 83 Is Apparel Manufacturing Coming Home? 86 MGFI McKinsey Global Fashion Index 92—99 Glossary 100 End Notes and Detailed Infographics 102 The State of Fashion 2019 The State of Fashion Foreword The year ahead is one that will go down in history. Greater China will for the first time in centuries overtake the US as the world’s largest fashion market. It will be a year of awakening after the reckoning of 2018 — a time for looking at opportunities, not just challenges. In the US and in the luxury sector it will be a year of optimism; for Europe and for struggling segments such as the mid-market, optimism may be in short supply.