Jeanne Lanvin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Percy Savage Interviewed by Linda Sandino: Full Transcript of the Interview

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH AN ORAL HISTORY OF BRITISH FASHION Percy Savage Interviewed by Linda Sandino C1046/09 IMPORTANT Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB United Kingdom +44 [0]20 7412 7404 [email protected] Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators. THE NATIONAL LIFE STORY COLLECTION INTERVIEW SUMMARY SHEET Ref. No.: C1046/09 Playback No.: F15198-99; F15388-90; F15531-35; F15591-92 Collection title: An Oral History of British Fashion Interviewee’s surname: Savage Title: Mr Interviewee’s forenames: Percy Sex: Occupation: Date of birth: 12.10.1926 Mother’s occupation: Father’s occupation: Date(s) of recording: 04.06.2004; 11.06.2004; 02.07.2004; 09.07.2004; 16.07.2004 Location of interview: Name of interviewer: Linda Sandino Type of recorder: Marantz Total no. of tapes: 12 Type of tape: C60 Mono or stereo: stereo Speed: Noise reduction: Original or copy: original Additional material: Copyright/Clearance: Interview is open. Copyright of BL Interviewer’s comments: Percy Savage Page 1 C1046/09 Tape 1 Side A (part 1) Tape 1 Side A [part 1] .....to plug it in? No we don’t. Not unless something goes wrong. [inaudible] see well enough, because I can put the [inaudible] light on, if you like? Yes, no, lovely, lovely, thank you. -

Paul Iribe (1883–1935) Was Born in Angoulême, France

4/11/2019 Bloomsbury Fashion Central - BLOOMSBURY~ Sign In: University of North Texas Personal FASHION CENTRAL ~ No Account? Sign Up About Browse Timelines Store Search Databases Advanced search --------The Berg Companion to Fashion eBook Valerie Steele (ed) Berg Fashion Library IRIBE, PAUL Michelle Tolini Finamore Pages: 429–430 Paul Iribe (1883–1935) was born in Angoulême, France. He started his career in illustration and design as a newspaper typographer and magazine illustrator at numerous Parisian journals and daily papers, including Le temps and Le rire. In 1906 Iribe collaborated with a number of avantgarde artists to create the satirical journal Le témoin, and his illustrations in this journal attracted the attention of the fashion designer Paul Poiret. Poiret commissioned Iribe to illustrate his first major dress collection in a 1908 portfolio entitled Les robes de Paul Poiret racontées par Paul Iribe . This limited edition publication (250 copies) was innovative in its use of vivid fauvist colors and the simplified lines and flattened planes of Japanese prints. To create the plates, Iribe utilized a hand coloring process called pochoir, in which bronze or zinc stencils are used to build up layers of color gradually. This publication, and others that followed, anticipated a revival of the fashion plate in a modernist style to reflect a newer, more streamlined fashionable silhouette. In 1911 the couturier Jeanne Paquin also hired Iribe , along with the illustrators Georges Lepape and Georges Barbier, to create a similar portfolio of her designs, entitled L’Eventail et la fourrure chez Paquin. Throughout the 1910s Iribe became further involved in fashion and added design for theater, interiors, and jewelry to his repertoire. -

The Male Fashion Bias Mr. Mark Neighbour a Practice

The Male Fashion Bias Mr. Mark Neighbour A Practice-Led Masters by Research Degree Faculty of Creative Industries Queensland University of Technology Discipline: Fashion Year of Submission: 2008 Key Words Male fashion Clothing design Gender Tailoring Clothing construction Dress reform Innovation Design process Contemporary menswear Fashion exhibition - 2 - Abstract Since the establishment of the first European fashion houses in the nineteenth century the male wardrobe has been continually appropriated by the fashion industry to the extent that every masculine garment has made its appearance in the female wardrobe. For the womenswear designer, menswear’s generic shapes are easily refitted and restyled to suit the prevailing fashionable silhouette. This, combined with a wealth of design detail and historical references, provides the cyclical female fashion system with an endless supply of “regular novelty” (Barthes, 2006, p.68). Yet, despite the wealth of inspiration and technique across both male and female clothing, the bias has largely been against menswear, with limited reciprocal benefit. Through an exploration of these concepts I propose to answer the question; how can I use womenswear patternmaking and construction technique to implement change in menswear design? - 3 - Statement of Original Authorship The work contained in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree or diploma at any other higher educational institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made. Signed: Mark L Neighbour Dated: - 4 - Acknowledgements I wish to thank and acknowledge everyone who supported and assisted this project. -

Women Surrealists: Sexuality, Fetish, Femininity and Female Surrealism

WOMEN SURREALISTS: SEXUALITY, FETISH, FEMININITY AND FEMALE SURREALISM BY SABINA DANIELA STENT A Thesis Submitted to THE UNIVERSITY OF BIRMINGHAM for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Modern Languages School of Languages, Cultures, Art History and Music The University of Birmingham September 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The objective of this thesis is to challenge the patriarchal traditions of Surrealism by examining the topic from the perspective of its women practitioners. Unlike past research, which often focuses on the biographical details of women artists, this thesis provides a case study of a select group of women Surrealists – chosen for the variety of their artistic practice and creativity – based on the close textual analysis of selected works. Specifically, this study will deal with names that are familiar (Lee Miller, Meret Oppenheim, Frida Kahlo), marginal (Elsa Schiaparelli) or simply ignored or dismissed within existing critical analyses (Alice Rahon). The focus of individual chapters will range from photography and sculpture to fashion, alchemy and folklore. By exploring subjects neglected in much orthodox male Surrealist practice, it will become evident that the women artists discussed here created their own form of Surrealism, one that was respectful and loyal to the movement’s founding principles even while it playfully and provocatively transformed them. -

© 2018 Weronika Gaudyn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2018 Weronika Gaudyn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED STUDY OF HAUTE COUTURE FASHION SHOWS AS PERFORMANCE ART A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Weronika Gaudyn December 2018 STUDY OF HAUTE COUTURE FASHION SHOWS AS PERFORMANCE ART Weronika Gaudyn Thesis Approved: Accepted: _________________________________ _________________________________ Advisor School Director Mr. James Slowiak Mr. Neil Sapienza _________________________________ _________________________________ Committee Member Dean of the College Ms. Lisa Lazar Linda Subich, Ph.D. _________________________________ _________________________________ Committee Member Dean of the Graduate School Sandra Stansbery-Buckland, Ph.D. Chand Midha, Ph.D. _________________________________ Date ii ABSTRACT Due to a change in purpose and structure of haute couture shows in the 1970s, the vision of couture shows as performance art was born. Through investigation of the elements of performance art, as well as its functions and characteristics, this study intends to determine how modern haute couture fashion shows relate to performance art and can operate under the definition of performance art. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee––James Slowiak, Sandra Stansbery Buckland and Lisa Lazar for their time during the completion of this thesis. It is something that could not have been accomplished without your help. A special thank you to my loving family and friends for their constant support -

Oddo Forum Lyon, January 7&8, 2016

Oddo Forum Lyon, January 7&8, 2016 Contents V Interparfums V Stock market V 2015 highlights V 2015 & 2016 highlights by brand V 2015 & 2016 results 2 Interparfums ___ 3 Interparfums V An independent "pure player" in the perfume and cosmetics industry V A creator, manufacturer and distributor of prestige perfumes based on a portfolio of international luxury brands 44 Brand portfolio V Brand licenses under exclusive worldwide agreements ° S.T. Dupont (1997 2016) ° Paul Smith (1998 2017) ° Van Cleef & Arpels (2007 2018) ° Montblanc (2010 2020 2025) ° Jimmy Choo (2010 2021) ° Boucheron (2011 2025) ° Balmain (2012 2024) ° Repetto (2012 2025) ° Karl Lagerfeld (2012 2032) ° Coach (2016 2026) V Proprietary brands ° Lanvin (perfumes) (2007) ° Rochas (perfumes & fashion) (2015) 5 License agreements V The license grants a right to use the brand V Over a long-term period (10 years, 15 years, 20 years or more) V In exchange for meeting qualitative obligations: ° Distribution network ° Number of launches ° Nature of advertising expenses… V and quantitative obligations ° Royalties (procedures for calculation, amount and minimum commitment) ° Advertising expenses (budgets, amount and minimum commitment) 6 The brands . A bold luxury fashion brand . Collections with distinctive style for an elegant and glamorous woman . 17 brand name stores . A 12-year license agreement executed in 2012 . One of the world’s most prestigious jewelers . A sensual and feminine universe . Boucheron creations render women resplendent . A 15-year license agreement executed in 2010 7 The brands . A brand created in 1941 with a rich and authentic American heritage . A global leader in premium handbags and lifestyle accessories . 3,000 doors worldwide . -

April 2018 Book List: Re-Make It

KNOCK KNOCK RE-MAKE IT READING LIST Knock Knock Children’s Museum (KKCM) is a community spark for engaging, playful learning experiences that inspire and support lifelong learning. We strive to be inclusive by making every aspect of our museum relevant and accessible to all. We recognize that responsive interactions are critical for children and adults to achieve their fullest potential in the context of relationships that are built on trust and respect. We believe in the development of the whole child with the goal of increasing early literacy skills while expanding knowledge and raising interest in STEAM subjects and careers. Books are an important part to our museum, with the Story Tree Learning Zones, featuring a library of over 400 books. These books organized around the themes of each Learning Zone are used daily in our programs, to introduce field trips, to guide art and maker shop activities, for story times and for visitors to enjoy. KKCM is excited to work with The Conscious Kid Library, an organization that promotes multicultural literacy, anti-bias and empowerment through creating access to diverse children’s books. Our goal is to make sure all visitors to our museum can see themselves and learn about the people, places, history and ideas that make up our diverse and wonderful world. Knock Knock’s theme for April is “Re-Make It” so all of the books featured on this list involve re-making, whether it’s weaving with used plastic bags, making musical instruments from trash, or transforming spaces, fashions, inventions or art. Knock Knock Children’s Museum • knockknockmuseum.org • The Conscious Kid • theconsciouskid.org RAINBOW WEAVER/TEJEDORA DEL ARCOÍRIS Linda Elovitz Marshall, Illustrated by Elisa Chavarri Ixchel wants to follow in the long tradition of weaving on backstrap looms, just as her mother, grandmother, and most Mayan women have done for more than two thousand years. -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book. -

Fragonard Magazine N°9 - 2021 a Year of PUBLICATION DIRECTOR and CHIEF EDITOR New Charlotte Urbain Assisted By, Beginnings Joséphine Pichard Et Ilona Dubois !

MAGAZINE 2021 9 ENGLISH EDITORIAL STAFF directed by, 2021, Table of Contents Agnès Costa Fragonard magazine n°9 - 2021 a year of PUBLICATION DIRECTOR AND CHIEF EDITOR new Charlotte Urbain assisted by, beginnings Joséphine Pichard et Ilona Dubois ! ART DIRECTOR Claudie Dubost assisted by, Maria Zak BREATHE SHARE P04 Passion flower P82 Audrey’s little house in Picardy AUTHORS Louise Andrier P10 News P92 Passion on the plate recipes Jean Huèges P14 Laura Daniel, a 100%-connected by Jacques Chibois Joséphine Pichard new talent! P96 Jean Flores & Théâtre de Grasse P16 Les Fleurs du Parfumeur Charlotte Urbain 2020 will remain etched in our minds as the in which we all take more care of our planet, CELEBRATE CONTRIBUTORS year that upturned our lives. Yet, even though our behavior and our fellow men and women. MEET P98 Ten years of acquisitions at the Céline Principiano, Carole Blumenfeld we’ve all suffered from the pandemic, it has And especially, let’s pledge to turn those words P22 Musée Jean-Honoré Fragonard leading the way Eva Lorenzini taught us how to adapt and behave differently. into actions! P106 A-Z of a Centenary P24 Gérard-Noel Delansay, Clément Trouche As many of you know, Maison Fragonard is a Although uncertainty remains as to the Homage to Jean-François Costa a familly affair small, 100% family-owned French house. We reopening of social venues, and we continue P114 Provence lifestyle PHOTOGRAPHERS enjoy a very close relationship with our teams to feel the way in terms of what tomorrow will in the age of Fragonard ESCAPE Olivier Capp and customers alike, so we deeply appreciate bring, we are over the moon to bring you these P118 The art of wearing perfume P26 Viva România! Eva Lorenzini your loyalty. -

Gazette Du Bon Ton: Reconsidering the Materiality of the Fashion Publication

Gazette du Bon Ton: Reconsidering the Materiality of the Fashion Publication by Michele L. Hopkins BA in Government and Politics, May 1989, University of Maryland A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Decorative Arts and Design History August 31, 2018 Thesis directed by Erin Kuykendall Assistant Professor of Decorative Arts & Design History ©2018 by Michele L. Hopkins All rights reserved ii Dedication To Mary D. Doering for graciously sharing her passion and extensive knowledge of costume history in developing the next generation of Smithsonian scholars. Thank you for your unwavering encouragement. This thesis is dedicated to you. iii Acknowledgments What strange phenomena we find in a great city, all we need do is stroll about with our eyes open. ~Charles Baudelaire The author wishes to gratefully acknowledge the guidance of Tanya Williams Wetenhall, Erin Kuykendall, and Kym Rice. To Elizabeth Deans Romariz, thank you for shaping my thesis topic and for inspiring me to strive for academic excellence beyond my comfort zone. The academic journey into the world of rare books changed my life. To April Calahan, thank you for your generosity in opening the vast resources of the Library Special Collections and College Archives (SPARC) at the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) to me. To Simon Kelly, my summer with you at the Saint Louis Art Museum introduced me to late nineteenth-century Paris, the center of art, fashion, commerce, and spectacle. Your rigorous research methods inform my work to this day, you are the voice in my head. -

Madeleine Vionnet Pdf, Epub, Ebook

MADELEINE VIONNET PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Betty Kirke,Issey Miyake | 244 pages | 05 Dec 2012 | CHRONICLE BOOKS | 9781452110691 | English | California, United States Madeleine Vionnet PDF Book This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Although she amassed a loyal clientele, the outbreak of World War I meant the temporarily closure of her thriving business. Vionnet worked out her designs by draping fabric on a half-size mannequin, which she set on a swiveling piano stool and turned like pottery on a wheel. And while restrained and disciplined, McCardell's work was hardly devoid of details: Her signature, even idiosyncratic, "McCardellisms" included severe, asymmetrical, wrap necklines, yards-long sashes, spaghetti-string ties, double-needle top stitching, metal hook-and-eye closures, and even studded leather cuffs. Insisting that "clothes should be useful," McCardell became one of the first designers to successfully translate high-styled, reasonably priced, impeccably cut clothing into the mass-production arena. This robe de style is from the last part of the designer's career; she retired in October 16, Throughout her life, she fought copyright battles, protecting the rights of the designer, signing her work, an action followed by several other couturiers. I separate my types into four divisions — fat women, thin women, tall women, and short women. Full circle skirts, neatly belted or sashed at the waist without crinolines underneath, a mandatory accessory for the New Look, created the illusion of the wasp waist. Yohannan, Kohle, and Nancy Nolf. Surprising color combinations were indicative of McCardell's work. Business Woman As well as an innovative designer and skilful craftswoman, Vionnet was an incredibly savvy businesswoman. -

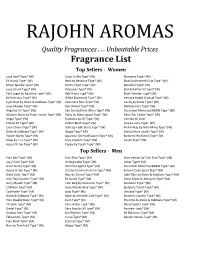

Fragrance List Print

Quality Fragrances . Unbeatable Prices Fragrance List Top Sellers - Women Love Spell Type* (W) Gucci Guilty Type* (W) Romance Type* (W) Ed Hardy Type*RAJOHN (W) Heat by Beyonce Type* (W)AROMASBlack by Kenneth Cole Type* (W) Moon Sparkle Type* (W) Jimmy Choo Type* (W) Beautiful Type* (W) Love Struck Type* (W) Pleasures Type* (W) Bombshell by VS Type* (W) Pink Sugar by Aquolina Type* (W) Reb'l Fleur Type* (W) Black Woman Type* (W) Be Delicious Type* (W) White Diamonds Type* (W) Versace Bright Crystsal Type* (W) Light Blue by Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Cashmere Mist Type* (W) Candy by Prada Type* (W) Issey Miyake Type* (W) Butt Naked Type* (W) Michael Kors Type* (W) Angel by VS Type* (W) Can Can by Paris Hilton Type* (W) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type* (W) Modern Muse by Estee Lauder Type* (W) Daisy by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Miss Dior Cherie Type* (W) Angel Type* (W) Euphoria by CK Type* (W) Lick Me All Over Chanel #5 Type* (W) Amber Blush Type* (W) Viva La Juicy Type* (W) Coco Chanel Type* (W) Halle by Halle Berry Type* (W) Pink Friday by Nicki Minaj Type* (W) Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Happy Type* (W) Dot by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Flower Bomb Type* (W) Japanese Cherry Blossom Type* (W) Burberry Weekend Type* (W) Glow by J. Lo Type* (W) Juicy Couture Type* (W) Coach Type* (W) Acqua Di Gio Type* (W) Poppy by Coach Type* (W) Top Sellers - Men Polo Red Type* (M) Polo Blue Type* (M) Grey Vetiver by Tom Ford Type* (M) Jay-Z Gold Type* (M) Unforgivable Type* (M) Usher Type* (M) Gucci Guilty Type* (M) Chrome Legend Type* (M) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type*