Until the Meat Falls Off the Bone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nutrition, Lifestyle and Diabetes-Risk of School Children in Derna

www.doktorverlag.de [email protected] Tel: 0641-5599888Fax:-5599890 Tel: D-35396 GIESSEN STAUFENBERGRING 15 STAUFENBERGRING VVB LAUFERSWEILERVERLAG VVB LAUFERSWEILER VERLAG VVB LAUFERSWEILER édition scientifique 9 783835 955103 ISBN 3-8359-5510-1 ISBN © KaYann -Fotolia.com © KaYann © JoseManuelGelpi-Fotolia.com VVB TAWFEG ELHISADI NUTRITION, LIFESTYLE AND DIABETES-RISK OF CHILDREN IN DERNA, LIBYA NUTRITION, LIFESTYLEANDDIABETES-RISKOF SCHOOL CHILDRENINDERNA,LIBYA TAWFEG A.ELHISADI Agrarwissenschaften, Ökotrophologie der Justus-Liebig-Universität Giessen INAUGURAL-DISSERTATION zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades VVB LAUFERSWEILER VERLAG VVB LAUFERSWEILER und Umweltmanagement im Fachbereich édition scientifique . Das Werk ist in allen seinen Teilen urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung ist ohne schriftliche Zustimmung des Autors oder des Verlages unzulässig. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung in und Verarbeitung durch elektronische Systeme. 1. Auflage 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Author or the Publishers. 1st Edition 2009 © 2009 by VVB LAUFERSWEILER VERLAG, Giessen Printed in Germany VVB LAUFERSWEILERédition scientifique VERLAG STAUFENBERGRING 15, D-35396 GIESSEN Tel: 0641-5599888 Fax: 0641-5599890 email: [email protected] www.doktorverlag.de Institut für Ernährungswissenschaft Justus-Liebig-Universität Giessen Nutrition, Lifestyle and Diabetes-risk of School Children in Derna, Libya INAUGURAL-DISSERTATION zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades im Fachbereich Agrarwissenschaften, Ökotrophologie und Umweltmanagement der Justus-Liebig-Universität Giessen eingereicht von Tawfeg A. A. Elhisadi aus Libyen Giessen 2009 Dekanin: Prof. Dr. I. U. Leonhäuser Prüfungsvorsitzende: Prof. Dr. A. Evers 1. -

Razorcake Issue #82 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California not-for-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

Restaurant Oriental Wa-Lok

RESTAURANT ORIENTAL WA-LOK DIRECCIÓN:JR.PARURO N.864-LIMA TÉLEFONO: (01) 4270727 RESTAURANT ORIENTAL WA-LOK BOCADITOS APPETIZER 1. JA KAO S/.21.00 Shrimp dumpling 2. CHI CHON FAN CON CARNE S/.17.00 Rice noodle roll with beef 3. CHIN CHON FAN CON LAN GOSTINO S/.20.00 Rice noodle roll with shrimp 4. CHIN CHON FAN SOLO S/.14.00 Rice noodle roll 5. CHIN CHON FAN CON VERDURAS S/.17.00 Rice noodle with vegetables 6. SAM SEN KAO S/.25.00 Pork, mushrooms and green pea dumplings 7. BOLA DE CARNE S/.19.00 Steam meat in shape of ball 8. SIU MAI DE CARNE S/.18.00 Siumai dumpling with beef 9. SIU MAI DE CHANCHO Y LANGOSTINO S/.18.00 Siumai dumpling with pork and shrimp 10. COSTILLA CON TAUSI S/.17.00 Steam short ribs with black beans sauce 11. PATITA DE POLLO CON TAUSI S/.17.00 Chicken feet with black beans 12. ENROLIADO DE PRIMAVERA S/.17.00 Spring rolls 13. ENROLLADO 100 FLORES S/.40.00 100 flowers rolls 14. WANTAN FRITO S/.18.00 Fried wonton 15. SUI KAO FRITO S/.20.00 Fried suikao 16. JAKAO FRITO S/.21.00 Fried shrimp dumpling Dirección: Jr. Paruro N.864-LIMA Tel: (01) 4270727 RESTAURANT ORIENTAL WA-LOK 17. MIN PAO ESPECIAL S/.13.00 Steamed special bun (baozi) 18. MIN PAO DE CHANCHO S/.11.00 Steamed pork bun (baozi) 19. MIN PAO DE POLLO S/.11.00 Steamed chicken bun (baozi) 20. MIN PAO DULCE S/.10.00 Sweet bun (baozi) 21. -

Ihaw Vegetables Rice Desserts

APPETIZERS MAIN COURSES Ukoy Adobong Manok sa Gata A combination of shrimp, vegetables and mongo sprouts Chicken prepared in a marinade of coconut milk, soy sauce, deep-fried in batter vinegar, garlic, and black peppercorns Lumpiang Ubod Pinalutong na Tadyang Heart of palm and shrimp roll served with sweetened soy Crispy, deep-fried beef ribs sauce, fresh or fried Bistek Tagalog Lumpiang Shanghai Sirloin steak with soy-lime sauce, served with sautéed onion Fried spring rolls filled with shrimp, pork and vegetables rings served with sweet chili sauce Crispy Pata Good for two persons Sisig Deep-fried pork knuckles The ultimate pulutan companion that goes with beer or steamed rice Kare Kare Oxtail stew in peanut sauce Chicharon Bulaklak Pork entrails deep-fried in vegetable oil Binagoongan Baboy Pork sautéed in shrimp paste Dulong Anchovies sautéed in olive oil, garlic and chili Lechon Kawali Deep-fried pork belly SALADS Pinalutong na Tilapia Ensaladang Talong at Kamatis at Manggang Hilaw Crispy deep-fried tilapia Vegetables with fish sauce and tomatoes Balesin Islander Salad IHAW – IHAW Mixed greens with a choice of dressings Chicken Inasal Inihaw na Liempo Manggang Hilaw at Bagoong Inihaw na Pusit Green mango with shrimp paste Inihaw na Sugpo Inihaw na Lapu-lapu Inihaw na Tilapia SOUPS Inihaw na Hito Binakol Fish fillet cubes boiled in coconut juice and minced tomato, served in a buko shell VEGETABLES Pinakbet Munggo Soup Ampalaya Guisado Mung bean soup Chop Suey Kangkong sa Lechon Bulalo Good for two persons Boiled beef shanks with native vegetables. RICE Sinigang na Hipon Good for 2-3 persons Garlic Rice Fresh prawns in sour broth with tomato, onions and native Steamed Rice vegetables Adobo Rice Sinigang na Baboy Good for 2-3 persons Pork in sour broth with tomato, onions and native vegetables DESSERTS Fresh Fruits in Season Single MAIN COURSES Platter Fried Chicken Leche Flan Half Buko Salad Whole Balesin Fruit Salad Halo-halo Adobong Manok Mais con Hielo Chicken prepared in a marinade of soy sauce, vinegar, garlic, Palitaw and black peppercorns Bibingka . -

Rubenfeld's Monsey Park Hotel

חג כשר ושמח! pa sso ver g r eet ing s • TOTALLY FREE CHECKING Wl'liave • BUDGET CHECKING • ISRAEL SCENIC CHECKS a bank • ALL-IN-ONE SAVINGS • CHAI BOND CERTIFICATES • TRAVEL CASH CARD for you • PERSONAL & BUSINESS LOANS MIDTOWN BROOKLYN 579 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10017 188 Montague Street, Brooklyn, N.Y. 11201 562 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10036 BRON X 301 East Fordham Road, Bronx, N.Y. 10458 WEST SIDE 1412 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10018 QUEENS 104-70 Queens Blvd., Forest Hills, N.Y. 11375 DOWNTOWN El Al Terminal, JFK Int’l. Airport 111 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10006 HEWLETT, LONG ISLAND 25 Broad Street, New York, N.Y. 10005 1280 Broadway, Hewlett, N.Y. 11557 Passover: Cantor, Seder, Services, Reserve now1 S• ■ Mg. •Glatt Kosher Cuisine Supervised by Rabbi David Cohen 4 • 3 delicious MEALS Do iMd Lis snacks) •FREE daily MASSAGE YOGA Exercise Classes NEW JERSEY־POSTURE• 3$♦ •Health Club-SAUNA,WHIRLPOOL •Heated INDOOR POOL RESORT • NfTELY DANCING* FOR YOUR HEALTH ent er t ainment •INDOOR, OUTDOOR AND PLEASURE TENNf$/GOLF available All Spa and Resort facilities Open open permitted days of Passover ALL YEAR ROUND ^Harbor Island Spa ON THE OCEAN WEST END, NEW JERSEY IELE (212)227-1051 / (201) 222-5800 Call for information & a Free Color Brochure I SUPERVISED DAY CAMP-NIGHT M.TROL נ. מ8נישעוויטץ ק8מפ8ני Genera/ Office: 340 HENDERSON STREET, JERSEY CITY, N.J. 07302 את זה תאכלו כל מיני האוכל אשר השם "מאנישעוויטץ" נקרא עליהם, כמו: ׳ מצה ותוצרת מצה וגם מצה־שמורה משעת קצירה; דנים ממולאים, מרק של בשר, עוף וירקות; חמיצות של סלק ועלי־שדה; מזון־תינוקות -

CONTACTLESS MENU Impress Your Guests!

Menu CONTACTLESS MENU OPEN THE CAMERA ON YOUR SMART PHONE HOLD IT OVER THE QR CODE TO VIEW OUR MENU www.facebook.com/Bodegadc Impress your guests! For both cocktail party and seated dinner events we offer preset or customized menus along with paella packages for groups of 10 or more. Please inquire at [email protected] Tablas Tabla de Quesos Españoles con 17 Acompañamientos Chef’s Selection of Spanish Cheeses and Accompaniments Tabla de Jamón Serrano con Manchego 19 Jamón Serrano with Manchego Cheese SOUPS Sopa de Lentejas 8 Lentil Soup with Chorizo Sausage Gazpacho Andaluz 8 Traditional Andalucían Chilled Gazpacho Soup Sopa de Pescado con Fideos 14 Traditional Seafood Broth with Shrimp, Clams, Mussels and Fideo Noodles SALADS Ensalada de Peras y Nueces 9 Field Green Salad with Pears, Walnuts and Goat Cheese tossed in a Honey Vinaigrette Ensalada de la Casa 9 Romaine Lettuce tossed in a Garlic Anchovy Dressing topped with shaved Idiazábal Cheese Ensalada de Tomate con Bonito del Norte 10 Beefsteak Tomatoes, Onions and Bonito Tuna COLD TAPAS Boquerones con Guindilla Vasca 9 Cured, Marinated Anchovies with Basque Pepper Aceitunas de la Casa con Guindilla Vasca 7 Marinated House Olives with Basque Peppers Tostada de Queso de Cabra con Miel 9 Toasted Bread with Goat Cheese and Honey Pan con Tomate y Jamón Serrano 9 Catalonian Tomato Bread with Jamón Serrano Pan con Tomate y Queso Manchego 8 Catalonian Tomato Bread with Manchego Cheese HOT TAPAS Pimientos del Piquillo a la Plancha 8 Seared Piquillo Peppers with Sea Salt Croquetas de Pollo -

Foods to Avoid

Foods to Avoid File: ....... Test Date: ......... Patient: .............. Doctor/Clinic: ................... APPLE Avoid also rosehip tea, apple cider, apple cider vinegar, apple juice, applesauce, crabapple & dried apples. Also found in some chutneys. For reintroduction into diet, place into Day 2. APRICOT Avoid also apricot juice, apricot oil & dried apricots. Also found in some chutneys. For reintroduction into diet, place into Day 3. ARTICHOKE Avoid also burdock root tea & cardoon tea. Can be pickled whole, or the tender base or heart can be canned or frozen while the stalk of the head can be blanched in soups and stews. For reintroduction into diet, place into Day 1. ASPARAGUS Avoid also asparagus tips, sprue, white asparagus. Can be found in soups quiches and soufflés. For reintroduction into diet, place into Day 3. AVOCADO Avoid also avocado oil and alligator pear. Can be found in salads, sauces, dips and mousses or as hor d'œuvre, and is the main ingredient in the mexican dish guacomole. For reintroduction into diet, place into Day 2. BASIL Avoid also pesto sauce and sweet basil. For reintroduction into diet, place into Day 2. BAY LEAF Avoid also sweet bay, bouquet garni, and laurel. Used in meat dishes, milk puddings, soups, stews and sweet white sauces. For reintroduction into diet, place into Day 1. BLACK BEANS Black, or turtle, beans are small roughly ovoid legumes with glossy black shells. The scientific name for black beans is Phaselous vulgaris, an epithet shared with many other popular bean varieties such as pinto beans, white beans, and kidney beans. Black beans are associated with Latin American cuisine in particular, although they can complement foods from many places. -

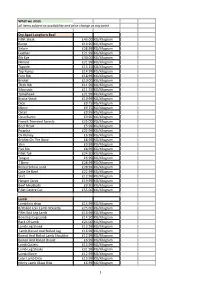

What We Stock All Items Subject to Availability and Price Change at Any Point

What we stock all items subject to availability and price change at any point Dry Aged Longhorn Beef Fillet Steak £45.00 KG/Kilogram Rump £19.95 KG/Kilogram Sirloin £28.99 KG/Kilogram Feather £21.99 KG/Kilogram Rib Eye £30.00 KG/Kilogram Minute £21.99 KG/Kilogram Topside £13.15 KG/Kilogram Top Rump £14.99 KG/Kilogram Fore Rib £18.99 KG/Kilogram Brisket £10.00 KG/Kilogram Thick Rib £11.99 KG/Kilogram Silverside £11.55 KG/Kilogram Tomahawk £21.99 KG/Kilogram Braise Steak £10.99 KG/Kilogram Dice £9.75 KG/Kilogram Mince £9.75 KG/Kilogram Oxtail £9.95 KG/Kilogram Osso Bucco £9.95 KG/Kilogram French Trimmed Forerib £25.00 KG/Kilogram Beef Heart £5.99 KG/Kilogram Picanha £22.99 KG/Kilogram Ox Kidney £6.99 KG/Kilogram Brisket On The Bone £8.99 KG/Kilogram Shin £9.99 KG/Kilogram Flat Rib £8.99 KG/Kilogram Fillet Tail £24.50 KG/Kilogram Tongue £6.99 KG/Kilogram T Bone £28.99 KG/Kilogram Rolled Sirloin Joint £28.99 KG/Kilogram Cote De Beof £22.99 KG/Kilogram Skirt £12.99 KG/Kilogram Hanger Steak £19.99 KG/Kilogram Beef Meatballs £9.50 KG/Kilogram Fillet Centre Cut £55.00 KG/Kilogram Lamb Lamb loin chop £14.99 KG/Kilogram B/Rolled Loin Lamb NoiseWe £25.00 KG/Kilogram Fillet End Leg Lamb £16.99 KG/Kilogram Boneless Leg Lamb £14.50 KG/Kilogram Rack Of Lamb £24.00 KG/Kilogram Lamb Leg Shank £13.99 KG/Kilogram Lamb Boned And Rolled Leg £16.99 KG/Kilogram Boned And Rolled Lamb Shoulder £12.99 KG/Kilogram Boned And Rolled Breast £6.99 KG/Kilogram Lamb Cutlets £13.99 KG/Kilogram Lamb Leg Steaks £21.99 KG/Kilogram Lamb Mince £12.99 KG/Kilogram Lean Lamb Dice -

International Benchmarking of the Small Goods Industry M.671

International benchmarking of the small goods industry M.671 Prepared by: Hassall & Associates Pty Ltd Published: December 1995 © 1998 This publication is published by Meat & Livestock Australia Limited ACN 081678364 (MLA). Where possible, care is taken to ensure the accuracy of information in the publication. Reproduction in whole or in part of this publication is prohibited without the prior written consent of MLA. Meat & Livestock Australia acknowledges the matching funds provided by the Australian Government and contributions from the Australian Meat Processor Corporation to support the research and development detailed in this publication. MEAT & LIVESTOCK AUSTRALIA -------------- EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. STUDY OBJECTIVES AND APPROACH 1.1 Why Benchmarking 1 1.2 Industry Benchmarking 1 1.3 Why Benchmark the Smallgoods Industry 4 1.4 Methodology 5 I. 5 Studies Related to the Smallgoods Industry 7 2. STRUCTURE OF THE AUSTRALIAN SMALLGOODS INDUSTRY 2.1 Overview of the Australian Smallgoods Industry 10 2.2 Smallgoods Industry Location and Composition II 2.3 Size ofEstablishment 11 2.4 Major Smallgoods Manufacturers 12 2.5 Smallgoods Industry Statistics 14 3. PERFORMANCE INDICATORS FOR SJX MAJOR AUSTRALIAN SMALLGOOD PRODUCERS 3.1 Coverage 29 3.2 Production 29 3.3 Meat and Other Materials Used 31 3.4 Labour 35 3.5 Labour Productivity 37 3.6 Unit Processing Costs 40 3.7 Labour Payments 40 3.8 Unit Material and Processing Costs 43 3.9 Human Resource Management Programs 43 4. SURVEY OF AUSTRALIAN INDUSTRY PERFORMANCE 4.1 Smallgoods Plant 46 4.2 -

Types of Sausage

Types of Sausage There are five varieties of sausages that are available in the commercial market. - Fresh sausage (e.g.: Brokwurst) - Cooked sausage (Mortadella) - Cooked-smoked sausage (Bologna, Frankfurters, Berliners) - Uncooked-smoked sausage (Kielbasa – the Polish sausage, Mettwurst) - Dry/semi dry sausage (Salami) SOME FAMOUS SAUSAGES: 1. ANDOUILLETTE French sausage made of pork, tripe and calf mesentery. 2. BERLINER from Berlin, made of pork and beef, flavored with salt and Sugar 3. BIERSCHENKEN a German sausage containing ham or ham fat + peppercorns and pistachio 4. BIERWURST a German beef and pork sausage flecked with fat and smoked. 5. BLACKPUDDING/BLOOD SAUSAGE there are many versions of this sausage or pudding, made out of pigs blood. The British one has oatmeal. The German version is called Blutwurst and the French one is known as Boudin Noir. The Spanish call it Morcilla, the Irish Drisheen and the Italians, Biroldo. They are usually sliced and sold. 6. BOCKWURST a delicately flavored, highly perishable German white sausage consisting of fresh pork and veal, chopped chives parsley, egg and milk. 7. BOLOGNA There are a number of versions of this popular Italian sausage. It usually has a mixture of smoked pork and beef. The English version is called Polony. 8. BOUDIN BLANC unlike boudin noir, this is a fresh sausage, made of pork, eggs, cream and seasoning 9. BRATWURST a German sausage made of minced pork / veal and spiced. 10. BUTIFARA a Spanish pork sausage flavored with garlic and spices – comes from the Catalonian region of Spain. 11. Cambridge an English sausage made from pork and flavored with herbs and spices. -

Rewriting the Haggadah: Judaism for Those Who Hold Food Close

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2020 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2020 Rewriting the Haggadah: Judaism for Those Who Hold Food Close Rose Noël Wax Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2020 Part of the Food Studies Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Wax, Rose Noël, "Rewriting the Haggadah: Judaism for Those Who Hold Food Close" (2020). Senior Projects Spring 2020. 176. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2020/176 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rewriting the Haggadah: Judaism for Those Who Hold Food Close Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Social Studies of Bard College by Rose Noël Wax Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2020 Acknowledgements Thank you to my parents for teaching me to be strong in my convictions. Thank you to all of the grandparents and great-grandparents I never knew for forging new identities in a country entirely foreign to them. -

Pisco Y Nazca Doral Lunch Menu

... ... ··············································································· ·:··.. .·•. ..... .. ···· : . ·.·. P I S C O v N A Z C A · ..· CEVICHE GASTROBAR miami spice ° 28 LUNCH FIRST select 1 CAUSA CROCANTE panko shrimp, whipped potato, rocoto aioli CEVICHE CREMOSO fsh, shrimp, creamy leche de tigre, sweet potato, ají limo TOSTONES pulled pork, avocado, salsa criolla, ají amarillo mojo PAPAS A LA HUANCAINA Idaho potatoes, huancaina sauce, boiled egg, botija olives served cold EMPANADAS DE AJí de gallina chicken stew, rocoto pepper aioli, ají amarillo SECOND select 1 ANTICUCHO DE POLLO platter grilled chicken skewers, anticuchera sauce, arroz con choclo, side salad POLLO SALTADO wok-seared chicken, soy and oyster sauce, onions, tomato wedges, arroz con choclo, fries RESACA burger 8 oz. ground beef, rocoto aioli, queso fresco, sweet plantains, ají panca jam, shoestring potatoes, served on a Kaiser roll add fried egg 1.5 TALLARín SALTADO chicken stir-fry, soy and oyster sauce, onions, tomato, ginger, linguini CHICHARRÓN DE PESCADO fried fsh, spicy Asian sauce, arroz chaufa blanco CHAUFA DE MARISCOS shrimp, calamari, chifa fried rice DESSERTS select 1 FLAN ‘crema volteada’ Peruvian style fan, grilled pineapple, quinoa tuile Alfajores 6 Traditional Peruvian cookies flled with dulce de leche SUSPIRO .. dulce de leche custard, meringue, passion fruit glaze . .. .. .. ~ . ·.... ..... ................................................................................. traditional inspired dishes ' spicy ..... .. ... Items subject to