A Discourse-Oriented Grammar of Eastern Bontoc. INSTITUTION Summer Inst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indigenous Peoples/Ethnic Minorities and Poverty Reduction: Regional Report

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES/ETHNIC MINORITIES AND POVERTY REDUCTION REGIONAL REPORT Roger Plant Environment and Social Safeguard Division Regional and Sustainable Development Department Asian Development Bank, Manila, Philippines June 2002 © Asian Development Bank 2002 All rights reserved Published June 2002 The views and interpretations in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Asian Development Bank. ISBN No. 971-561-438-8 Publication Stock No. 030702 Published by the Asian Development Bank P.O. Box 789, 0980, Manila, Philippines FOREWORD his publication was prepared in conjunction with an Asian Development Bank (ADB) regional technical assistance (RETA) project on Capacity Building for Indigenous Peoples/ T Ethnic Minority Issues and Poverty Reduction (RETA 5953), covering four developing member countries (DMCs) in the region, namely, Cambodia, Indonesia, Philippines, and Viet Nam. The project is aimed at strengthening national capacities to combat poverty and at improving the quality of ADB’s interventions as they affect indigenous peoples. The project was coordinated and supervised by Dr. Indira Simbolon, Social Development Specialist and Focal Point for Indigenous Peoples, ADB. The project was undertaken by a team headed by the author, Mr. Roger Plant, and composed of consultants from the four participating DMCs. Provincial and national workshops, as well as extensive fieldwork and consultations with high-level government representatives, nongovernment organizations (NGOs), and indigenous peoples themselves, provided the basis for poverty assessment as well as an examination of the law and policy framework and other issues relating to indigenous peoples. Country reports containing the principal findings of the project were presented at a regional workshop held in Manila on 25–26 October 2001, which was attended by representatives from the four participating DMCs, NGOs, ADB, and other finance institutions. -

Municipality of La Trinidad BARANGAY LUBAS

Republic of the Philippines Province of Benguet Municipality of La Trinidad BARANGAY LUBAS PHYSICAL AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC PROFILE I. PHYSICAL PROFILE Geographic Location Barangay Lubas is located on the southern part of the municipality of La Trinidad. It is bounded on the north by Barangay Tawang and Shilan, to the south by Barangay Ambiong and Balili, to the east by Barangay Shilan, Beckel and Ambiong and to the west by Barangay Tawang and Balili. With the rest of the municipality of La Trinidad, it lies at 16°46’ north latitude and 120° 59 east longitudes. Cordillera Administrative Region MANKAYAN Apayao BAKUN BUGUIAS KIBUNGAN LA TRINIDAD Abra Kalinga KAPANGAN KABAYAN ATOK TUBLAY Mt. Province BOKOD Ifugao BAGUIO CITY Benguet ITOGON TUBA Philippines Benguet Province 1 Sally Republic of the Philippines Province of Benguet Municipality of La Trinidad BARANGAY LUBAS POLITICAL MAP OF BARANGAY LUBAS Not to Scale 2 Sally Republic of the Philippines Province of Benguet Municipality of La Trinidad BARANGAY LUBAS Barangay Tawang Barangay Shilan Barangay Beckel Barangay Balili Barangay Ambiong Prepared by: MPDO La Trinidad under CBMS project, 2013 Land Area The Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) Cadastral survey reveals that the land area of Lubas is 240.5940 hectares. It is the 5th to the smallest barangays in the municipality occupying three percent (3%) of the total land area of La Trinidad. Political Subdivisions The barangay is composed of six sitios namely Rocky Side 1, Rocky Side 2, Inselbeg, Lubas Proper, Pipingew and Guitley. Guitley is the farthest and the highest part of Lubas, connected with the boundaries of Beckel and Ambiong. -

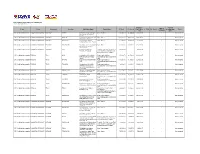

List of KALAHI-CIDSS Subprojects - MAKILAHOK As of February 01, 2019

List of KALAHI-CIDSS Subprojects - MAKILAHOK as of February 01, 2019 Estimated Physical Date of Region Province Municipality Barangay Sub-Project Name Project Type KC Grant LCC Amount Total Project No. Of HHsDate Started Accomplishme Status Completion Cost nt (%) CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA ANABEL Construction of One Unit One School Building 1,181,886.33 347,000.00 1,528,886.33 / / Not yet started Storey Elementary School Building CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA BEKIGAN Construction of Sumang-Paitan Water System 1,061,424.62 300,044.00 1,361,468.62 / / Not yet started Village Water System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA BELWANG Construction of Pikchat- Water System 471,920.92 353,000.00 824,920.92 / / Not yet started Pattiging Village Water System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA SACASACAN Rehabilitation of Penged Maballi- Water System 312,366.54 845,480.31 1,157,846.85 / / Not yet started Sacasshak Village Water Supply System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA SACLIT Improvement of Wetig- Footpath / Foot Trail / Access Trail 931,951.59 931,951.59 / / Not yet started Takchangan Footpath (may include box culvert/drainage as a component for Footpath) CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]IFUGAO TINOC AHIN Construction of 5m x 1000m Road (may include box 251,432.73 981,708.84 1,233,141.57 / / Not yet started FMR Along Telep-Awa-Buo culvert/drainage as a component for Section road) -

Municipal Government of Sadanga, Mountain Province

MUNICIPAL GOVERNMENT OF SADANGA, MOUNTAIN PROVINCE CITIZEN’S CHARTER 2020 (1st Edition) I. MANDATE: Deriving its mandate from the Local Government Code of 1991, also known as RA 7160, the mission to follow the people’s welfare under Section 16 of the Code, to wit: General Welfare: Every LGU shall exercise the powers expressly granted, those necessarily implied therefrom, as well as powers, necessary, appropriate, or incidental for its efficient and effective governance and those which are essential to the promotion of the general welfare within their respective territorial jurisdictions. LGU shall ensure and support among other things, the preservation and enrichment of culture, promote health and safety, enhance the right of the people to a balance ecology, encourage and support the development of appropriate and self-reliant, scientific and technological capabilities, improve public morals, enhance economic prosperity and social justice, promote full employment among their residents, maintain peace and order, and preserve the comfort and convenience of the inhabitant. II. VISION: “ADAYSA NA SADANGA” Dream paradise in the Gran Cordillera that is adaptive, resilient and vibrant community with politically matured, culturally enriched, peace loving, spiritually, strengthened, healthy and child friendly people enjoying a robust economy in a safe and sustainable environment, led by committed and proactive leaders in a participatory and collective governance. III. MISSION: Lead the people to be at pace with the changing times by pursuing equitable socio-economic growth, optimizing resources, improving the quality and delivery of basic services and prudently putting in place relevant infrastructures and socio- economic activities yet keeping intact the locality’s natural endowments and ecological balance while promoting peace and enhancing our indigenous cultural heritage. -

Republic of the Philippines Department of Public Works and Highways

Republic of the Philippines Department of Public Works and Highways ANNUAL PROCUREMENT PLAN (APP) FOR CY 2014 CORDILLERA ADMINISTRATIVE REGION (CAR) Procurement Project Cost/ Pre- Posting Pre-Bid Submission Post Award No. Contract Package Description Method ABC (Php) Procurement Advertisement Conference and Receipt Bid Evaluation Qualification of Conference of Bids Evaluation Contract CORDILLERA ADMINISTRATIVE REGION (CAR) 001 Mt Province-Ilocos Sur via Tue Rd., Section 1: Public Bidding P 54,930,000.00 Nov. 08, 2013 Nov. 11, 2013 Nov. 20, 2013 Dec. 02, 2013 Dec. 04, 2013 Dec. 09, 2013 Jan. 14, 2014 K0388+900 - K0389+500, K0393+500 - K0393+856; Section 2: K0398+000 - K0398+ 578, K0399+728 - K0399+811; Section 3 K0412+165 - K0412+942, K0413+327 - K0413+354, K0413+368 - K0413+400 002 Gurel-Bokod-Kabayan-Buguias-Abatan Rd., Public Bidding P 60,110,000.00 Nov. 08, 2013 Nov. 11, 2013 Nov. 20, 2013 Dec. 02, 2013 Dec. 04, 2013 Dec. 09, 2013 Jan. 14, 2014 K0352+560-K0353+180, K0353+397-K0354+875 003 Balili-Suyo-Sagada Road Leading to Sagada Caves, Public Bidding P 96,210,000.00 Nov. 08, 2013 Nov. 11, 2013 Nov. 20, 2013 Dec. 02, 2013 Dec. 04, 2013 Dec. 09, 2013 Jan. 14, 2014 Rice Terraces and Water Falls, Bontoc and Sagada, Mt.Province(DSTD) 004 Jct Talubin-Barlig-Natonin-Paracelis-Callacad Public Bidding P 53,780,000.00 Nov. 18, 2013 Nov. 21, 2013 Nov. 28, 2013 Dec. 10, 2013 Dec. 13, 2013 Dec. 17,2013 Jan. 14, 2014 Rd., K0406+922 - K0408+556 005 Maba-ay-Abatan,Bauko road leading to various Public Bidding P 94,560,000.00 Nov. -

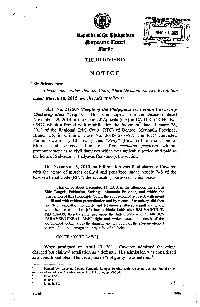

Gr 212564 2015.Pdf

' .. •' ~ l\epublit- of tbe l)lJtlipptnes &upreme teourt ;llanila TIDRD DIVISION NOTICE · Sirs/Mesdames: Please take notice that the Court, Third Division, issued a Resolution dated. March 18, 2015, which reads as follows: G.R. No. 212564 (People of the Philippines vs. Fermin Cawaren y Chakiwag alias "Aray'?. - This is an appeal from the Decision1 dated November 29, 2013 of the Court of Appeals (CA) in CA-G.R. CR-HC No. 05472 which affirmed with modification the Judgment2 dated January 26, 2012 of the Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Bontoc, Mountain Province, Branch 35, in Criminal Case No. 2010-12-16-88. The RTC convicted Fermin Cawaren y Chakiwag alias "Aray" (Cawaren) of the crime of Murder and sentenced him to s4ffer reclusion perpetua without pronouncement as to civil damages which was amicably settled and paid to the heirs of Salvador T. Padya-os (Salvador), the victim. On December 16, 2010, an information was filed charging Cawaren with the crime of murder defined and penalized under Article 248 of the Revised Penal Code (RPC), the accusatory portion of which reads: That on or about December 14, 2010, in the afternoon thereof, at Sitio Fangek, Poblacion, Sadanga, Mountain Province, and within the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court, the above-named accused, with intent to kill and with evident premeditation and by means of treachery, did then and there willfully, Unlawfully and feloniously attack, assault and x x .x with the use of a six[ ](6) inches blade knife stab SALVADOR T. PADYA-OS, thereby inflicting upon the latter, stab wound, .4th ICS PARAVERTEBRAL ARFP right and which caused the death of the aforenamed victim, all to the damage and prejudice of the aforementioned victim, all to the damage and prejudice of his heirs. -

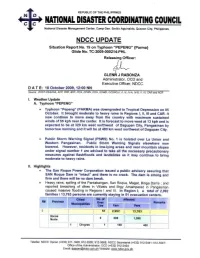

NDCC Update Sitrep No. 19 Re TY Pepeng As of 10 Oct 12:00NN

2 Pinili 1 139 695 Ilocos Sur 2 16 65 1 Marcos 2 16 65 La Union 35 1,902 9,164 1 Aringay 7 570 3,276 2 Bagullin 1 400 2,000 3 Bangar 3 226 1,249 4 Bauang 10 481 1,630 5 Caba 2 55 193 6 Luna 1 4 20 7 Pugo 3 49 212 8 Rosario 2 30 189 San 9 Fernand 2 10 43 o City San 10 1 14 48 Gabriel 11 San Juan 1 19 111 12 Sudipen 1 43 187 13 Tubao 1 1 6 Pangasinan 12 835 3,439 1 Asingan 5 114 458 2 Dagupan 1 96 356 3 Rosales 2 125 625 4 Tayug 4 500 2,000 • The figures above may continue to go up as reports are still coming from Regions I, II and III • There are now 299 reported casualties (Tab A) with the following breakdown: 184 Dead – 6 in Pangasinan, 1 in Ilocos Sur (drowned), 1 in Ilocos Norte (hypothermia), 34 in La Union, 133 in Benguet (landslide, suffocated secondary to encavement), 2 in Ifugao (landslide), 2 in Nueva Ecija, 1 in Quezon Province, and 4 in Camarines Sur 75 Injured - 1 in Kalinga, 73 in Benguet, and 1 in Ilocos Norte 40 Missing - 34 in Benguet, 1 in Ilocos Norte, and 5 in Pangasinan • A total of 20,263 houses were damaged with 1,794 totally and 18,469 partially damaged (Tab B) • There were reports of power outages/interruptions in Regions I, II, III and CAR. Government offices in Region I continue to be operational using generator sets. -

Heirloom Recipes of the Cordillera

Heirloom Recipes of the Cordillera Partners for Indigenous Knowledge Philippines HEIRLOOM RECIPES OF THE CORDILLERA Philippine Copyright 2019 Philippine Task Force for Indigenous People’s Rights (TFIP) Partners for Indigenous Knowledge Philippines (PIKP) This work is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License (CC BY-NC). Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purpose is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holders. Published by: Philippine Task Force for Indigenous People’s Rights (TFIP) #16 Loro Street, Dizon Subdivision, Baguio City, Philippines And Partners for Indigenous Knowledge Philippines (PIKP) #54 Evangelista Street, Leonila Hill, Baguio City, Philippines With support from: VOICE https://voice.global Editor: Judy Cariño-Fangloy Illustrations: Sixto Talastas & Edward Alejandro Balawag Cover: Edward Alejandro Balawag Book design and layout: Ana Kinja Tauli Project Team: Marciana Balusdan Jill Cariño Judy Cariño-Fangloy Anna Karla Himmiwat Maria Elena Regpala Sixto Talastas Ana Kinja Tauli ISBN: 978-621-96088-0-0 To the next generation, May they inherit the wisdom of their ancestors Contents Introduction 1 Rice 3 Roots 39 Vegetables 55 Fish, Snails and Crabs 89 Meat 105 Preserves 117 Drinks 137 Our Informants 153 Foreword This book introduces readers to foods eaten and shared among families and communities of indigenous peoples in the Cordillera region of the Philippines. Heirloom recipes were generously shared and demonstrated by key informants from Benguet, Ifugao, Mountain Province, Kalinga and Apayao during food and cooking workshops in Conner, Besao, Sagada, Bangued, Dalupirip and Baguio City. -

NDRRMC Update Re Sitrep No 6 Re TY PEDRING 28 Sep 2011

B. EFFECTS OF TROPICAL STORM PEDRING 1. AFFECTED POPULATION (TAB A) • Total number of population affected in 349 barangays / 78 municipalities / 17 cities in the 22 provinces of Regions I, II, III, IV-A, IV-B, V, CAR and NCR is: 35,273 families / 171, 570 persons • Total number of population currently served inside and outside evacuation centers is 10,932 families / 52,993 persons INSIDE 153 ECs 9,826 families / 47,709 persons OUTSIDE ECs (relatives/friends) 1,106 families / 5,284 persons 2. CASUALTIES: (TAB B) Dead 18 Injured 13 Missing 35 Rescued/Survivors 108 3. STATUS OF STRANDEES (as of 5:00 PM, 27 September 2011) – PCG (TAB C) • A total of 3,365 passengers; 121 trucks; 31 cars; 45 buses; 212 rolling cargoes; 38 vessels and 20 Mbcs are still stranded in 22 ports while 20 vehicles/ Mbcs are taking shelter in sea ports of affected areas. 4. DAMAGES TO PROPERTIES (TAB D) • Initial cost of damages to 46 school buildings and crops amounted to PhP100,264,840.63: School Buildings (84,060,000.00) and Agriculture (16,204,840.63) 5. STATUS OF LIFELINES: a. ROADS AND BRIDGES CONDITION (TAB E) • As of 8:00 PM, 27 September 2011, total of 61 road sections are reported impassable in Regions I (1), Region II (1), Region III (7), Region IV-A (2), Region V (3), CAR (27) and NCR (20). b. POWER INTERRUPTIONS • National Grid Corporation of the Philippines The following provinces experienced power outage due to damaged NGCP’s transmission facilities and / or damaged distribution utilities of electric cooperatives: Province Percentage of Power Loss Ilocos Norte 24 Nueva Vizcaya 99 Cagayan 51 Isabela 90 La Union 36 Bataan 75 Nueva Ecija 86 Pampanga 33 2 Zambales 95 Benguet 100 Laguna 52 • MERALCO Out of 4,919,012 total customers served by MERALCO, about 20.95% or 1,030,301 consumers are still without power: Area / Province Number of Consumers Metro Manila 695,074 Batangas 27,690 Bulacan 253,894 Cavite 253,894 Laguna 2,256 Pampanga 3,347 Quezon 1,201 Rizal 4,273 6. -

FY2015 CAR Program 01202015.Xlsx 1 / 44 2/5/2015 \ 4:04 PM FY 2015 DPWH Infrastructure Program Based on GAA Cordillera Administrative Region

FY2015 CAR Program 01202015.xlsx 1 / 44 2/5/2015 \ 4:04 PM FY 2015 DPWH Infrastructure Program Based on GAA Cordillera Administrative Region Released to/ Physical Amount UACS Programs/Activities/Projects Scope of Work To be Target (P'000) Implemented by CORDILLERA ADMINISTRATIVE REGION 10,574,185 ABRA DISTRICT ENGINEERING OFFICE/ Lone Legislative District 868,825 I. PROGRAMS 710,195 1. Operations 710,195 a. MFO 1 - National Road Network Services 687,047 1. Asset Preservation of National Roads 251,306 a. Preventive Maintenance based on Pavement Management System/ Highway 80,706 Development and Management-4 (HDM-4) (Intermittent Sections) - Reblocking of Shattered Blocks (4.5m/block) Secondary Roads 11.273 KM 80,706 165003012300010 1. Abra-Cervantes Rd - Preventive Maintenance 0.323 KM 2,285 Abra DEO/ K0443+000 - K0443+323 Abra DEO 165003012300011 2. Abra-Ilocos Norte Rd - K0409+025 - K0409+854, Preventive Maintenance 10.950 KM 78,421 CAR RO/ K0411+081 - K0411+234, K0414+761 - K0419+000, CAR RO K0421+800 - K0423+456, K0423+472 - K0427+000 b. Rehabilitation/ Reconstruction of National Roads with Slips, Slope Collapse, and 125,000 Landslide Arterial Roads - KM 125,000 165003012400001 1. Abra-Kalinga Rd - Slope Protection - KM 125,000 CAR RO/ K0462+470, K0467+550, K0469+900, K0483+070 CAR RO c. Construction/Upgrading/Rehabilitation of Drainage along National Roads 9.353 KM 45,600 165003012600006 1. Abra-Ilocos Norte Rd - Construction/ Rehabilitation of 1.545 KM 7,600 Abra DEO/ K0409+(-690) - K0409+276, Drainage/Protection Works Abra DEO along National Roads K0410+200 - K0410+779 165003012600008 2. -

Tingguian Abra Rituals

TINGGUIAN ABRA RITUALS By Philian Louise C. Weygan Published by ICBE in “Cordillera Rituals as a Way of Life” edited by Yvonne Belen (2009) ICBE, The Netherlands A. THE TINGUIANS/TINGGUIAN The Tinguians/Tingguians are indigenous people groups of the province of Abra, located in the Cordillera region of northern Philippines. As of 2003, they were found in all of the 27 municipalities compromising 40% of the total population and occupying almost 70% of the total land area. The lowland Tinguian inhabit lowland Abra and the mountain area is where the “Upland Tinguian” originally habited. As of the present times Bangued, the capital town, is inhabited by a representation of all the tribes of Abra as well as migrants. The word “Tingguian” is traced to the Malay root word “tinggi” meaning high, mountains, elevated, upper. However, the people refer to themselves as “Itneg, Gimpong or Idaya-as” or based on their 12 sub-people group. The 12 ethno linguistic groups are the Inlaud, Binongan, Masadiit, Banao, Gubang, Mabaka, Adasen, Balatok, Belwang, Mayudan, Maengs and the Agta or Negrito. In this presentation, some terms (like sangasang, singlip ) are used to mean different things in a different context. It would be prudent to say that the terms used could have same or similar essence and significance but are practiced in different aspects of community (ili) or individual’s life. Likewise, some Tinguian terms are similar with those of other tribes of Mountain Province and Kalinga, but may not mean exactly the same thing. Therefore caution should be practiced in generalizing the meaning and a generic practice of rituals mentioned. -

SB-16-CRM-0323-0324 People Vs Magdalena K

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES SANDIGANBAYAN Quezon City Third Division PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Crim. Case No. Plaintiff, SB-16-CRM-0323 to 0324 For: Violation of Section 3(e) of Republic Act No. 3019 -versus- MAGDALENA K. LUPOYON, Present: ET AL., Cabotaje-Tang, A.M., PJ., Accused. Chairperson Fernandez, B.,R, J. and Moreno, R.,B, J. PROMULGATED: Tf?62P'V 'R~y ~! Z[;J:2-J x--------------------------------------------------------- DECISION Moreno, J.: Accused Magdalena Kintapan Lupoyon and Albert Tenglab Marafo are charged before this Court with violation of Section 3(e) of Republic Act (R.A.) No. 3019, as amended. The Information reads as follows: That on 26 June 2009 or sometime prior or subsequent thereto, in the Municipality of Barlig, Mountain Province, Philippines, and within the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court; the above named accused, MAGDALENA K. LUPOYON, a high ranking public officer with salary grade 27, being then the Municipal Mayor and ALBERT TENGLAB MARAFO, then Municipal Treasurer, both of the Municipality of Barlig, Mountain Province; while in the performance of their official and/or administrative functions; conspiring with one another, committing the offense in relation to their office, acting with evident bad faith or gross inexcusable negligence; did then and there wilfully, unlawfully and criminally cause undue injury to the Municipality of Barlig, Mountain 1 Province by causing the repair or renovation of the pathway leading to ~ I tt AD i : /-;~ Decision SB-16-CRM-0323-0324 People v. Lupoyon, et 01. x-----------------x Mount Amuyao in the amount of Fifty Thousand Pesos (Php50, 000. 00), without public bidding as required under Section 10 of Republic Act No.