Free Land and Peasant Proprietorship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PREHISTORIC JERSEY People and Climate of the Ice Age

PREHISTORIC JERSEY People and climate of the Ice Age Lesson plan Fact sheets Quiz sheets Story prompts Picture sheets SUPPORTED BY www.jerseyheritage.org People and climate of the Ice Age .............................................................................................................................................................................. People and climate of plan the Ice Age Lesson Introduction Lesson Objectives Tell children that they are going to be finding To understand that the Ice out about the very early humans that lived during Age people were different the Ice Age and the climate that they lived in. species. Explain about the different homo species of To understand there are two main early humans we study, early humans and what evidence there is for this. Neanderthals and Homo Sapiens. Discuss what a human is and the concept of To develop the appropriate evolution. use of historical terms. To understand that Jersey has Ask evidence of both Neanderthals How might people in the Ice Age have lived? and Early Homo Sapiens on the Where did they live? island. Who did they live with? How did they get food and what clothes did they Expected Outcomes wear? Why was it called the Ice Age? All children will be able to identify two different sets of What did the landscape look like? people living in the Ice Age. Explain that the artefacts found in Jersey are Most children will able to tools made by people and evidence left by the identify two different sets of early people which is how they can tell us about people living in the Ice Age and the Ice Age. describe their similarities and differences. Some children will describe two different sets of people Whole Class Work living in the Ice Age, describe Read and discuss the page ‘People of the their similarities and differences Ice Age’ which give an overview of the Ice Age and be able to reflect on the people and specifically the Neanderthals and evolution of people according Homo Sapiens. -

Patrick John Cosgrove

i o- 1 n wm S3V NUI MAYNOOTH Ollfctel na t-Ciraann W* huatl THE WYNDHAM LAND ACT, 1903: THE FINAL SOLUTION TO THE IRISH LAND QUESTION? by PATRICK JOHN COSGROVE THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH HEAD OF DEPARTMENT: Professor R. V. Comerford Supervisor of Research: Dr Terence Dooley September 2008 Contents Acknowledgements Abbreviations INTRODUCTION CHAPTER ONE: THE ORIGINS OF THE WYNDHAM LAND BILL, 1903. i. Introduction. ii. T. W. Russell at Clogher, Co. Tyrone, September 1900. iii. The official launch of the compulsory purchase campaign in Ulster. iv. The Ulster Farmers’ and Labourers’ Union and Compulsory Sale Organisation. v. Official launch of the U.I.L. campaign for compulsory purchase. vi. The East Down by-election, 1902. vii. The response to the 1902 land bill. viii. The Land Conference, ix. Conclusion. CHAPTER TWO: INITIAL REACTIONS TO THE 1903 LAND BILL. i. Introduction. ii. The response of the Conservative party. iii. The response of the Liberal opposition to the bill. iv. Nationalist reaction to the bill. v. Unionist reaction to the bill. vi. The attitude of Irish landlords. vii. George Wyndham’s struggle to get the bill to the committee stage. viii. Conclusion. CHAPTER THREE: THE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES THAT FORGED THE WYNDHAM LAND ACT, 1903. i. Introduction. ii. The Estates Commission. iii. The system of price‘zones’. iv. The ‘bonus’ and the financial clauses of Wyndham’s Land Bill. v. Advances to tenant-purchasers. vi. Sale and repurchase of demesnes. vii. The evicted tenants question. viii. The retention of sporting and mineral rights. -

The Story of New Jersey

THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY HAGAMAN THE UNIVERSITY PUBLISHING COMPANY Examination Copy THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY (1948) A NEW HISTORY OF THE MIDDLE ATLANTIC STATES THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY is for use in the intermediate grades. A thorough story of the Middle Atlantic States is presented; the context is enriohed with illustrations and maps. THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY begins with early Indian Life and continues to present day with glimpses of future growth. Every aspect from mineral resources to vac-| tioning areas are discussed. 160 pages. Vooabulary for 4-5 Grades. List priceJ $1.28 Net price* $ .96 (Single Copy) (5 or more, f.o.b. i ^y., point of shipment) i^c' *"*. ' THE UNIVERSITY PUBLISHING COMPANY Linooln, Nebraska ..T" 3 6047 09044948 8 lererse The Story of New Jersey BY ADALINE P. HAGAMAN Illustrated by MARY ROYT and GEORGE BUCTEL The University Publishing Company LINCOLN NEW YORK DALLAS KANSAS CITY RINGWOOD PUBLIC LIBRARY 145 Skylands Road Ringwood, New Jersey 07456 TABLE OF CONTENTS NEW.JERSEY IN THE EARLY DAYS Before White Men Came ... 5 Indian Furniture and Utensils 19 Indian Tribes in New Jersey 7 Indian Food 20 What the Indians Looked Like 11 Indian Money 24 Indian Clothing 13 What an Indian Boy Did... 26 Indian Homes 16 What Indian Girls Could Do 32 THE WHITE MAN COMES TO NEW JERSEY The Voyage of Henry Hudson 35 The English Take New Dutch Trading Posts 37 Amsterdam 44 The Colony of New The English Settle in New Amsterdam 39 Jersey 47 The Swedes Come to New New Jersey Has New Jersey 42 Owners 50 PIONEER DAYS IN NEW JERSEY Making a New Home 52 Clothing of the Pioneers .. -

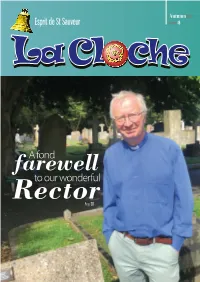

48 St Saviour Q3 2020.Pdf

Autumn2020 Esprit de St Sauveur Edition 48 farewellA fond Rectorto our wonderful Page 30 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Autumn 2020 St Saviour Parish Magazine p3 From the Editor Featured Back on Track! articles La Cloche is back on track and we have a full magazine. There are some poems by local From the Constable poets to celebrate Liberation and some stories from St Saviour residents who were in Jersey when the Liberation forces arrived on that memorable day, 9th May 1945. It is always enlightening to read and hear of others’ stories from the Occupation and Liberation p4 of Jersey during the 1940s. Life was so very different then, from now, and it is difficult for us to imagine what life was really like for the children and adults living at that time. Giles Bois has submitted a most interesting article when St Saviour had to build a guardhouse on the south coast. The Parish was asked to help Grouville with patrolling Liberation Stories the coast looking for marauders and in 1690 both parishes were ordered to build a guardhouse at La Rocque. This article is a very good read and the historians among you will want to rush off to look for our Guardhouse! Photographs accompany the article to p11 illustrate the building in the early years and then later development. St Saviour Battle of Flowers Association is managing to keep itself alive with a picnic in St Paul’s Football Club playing field. They are also making their own paper flowers in different styles and designs; so please get in touch with the Association Secretary to help with Forever St Saviour making flowers for next year’s Battle. -

Migration from Jersey to New Zealand in the 1870S

Migration from Jersey to New Zealand in the 1870s Version 3.0 Draft for comment, June 2019 Mark Boleat Comments welcome. Please send to [email protected] MIGRATION FROM JERSEY TO NEW ZEALAND IN THE 1870’S 1 Contents Introduction 3 1. The early migrants 4 2. The context for the 1872-1875 migration 6 3. The number of migrants 11 4. Why migration from Jersey to New Zealand was so high 15 5. The mechanics of the emigration 19 6. Characteristics of the emigrants 27 7. Where the emigrants settled 31 8. Prominent Jersey people and Jersey links in New Zealand 34 9. The impact on Jersey 40 Appendix 1 – sailings to New Zealand with Jersey residents, 42 1872-75– list of Jersey emigrants Appendix 2 – list of Jersey emigrants to New Zealand, 1872-75 45 References 56 MIGRATION FROM JERSEY TO NEW ZEALAND IN THE 1870’S 2 Introduction Over 500 people emigrated from Jersey to New Zealand between 1873 and 1874, and over the same period some 300 emigrated to Australia. By any standards this was mass migration comparable with the mass migration into Jersey in the 1830s and 1840s. Why and how did this happen, what sort of people were the emigrants and where did they settle in New Zealand? This paper seeks to explore these issues in respect of the emigration to New Zealand, although much of the analysis would be equally applicable to the emigration to Australia. The paper could be written only because of the excellent work by Keith Vautier in compiling a comprehensive database of 900 Channel Islanders who migrated to Australia and New Zealand. -

Gardien of Our Island Story

Gardien of our Island story. 2016/2017 ANNUAL REVIEW jerseyheritage.org Registered charity:Registered 161 charity: 161 INTRODUCTION CONTENTS Introduction 03 Jersey: Ice Age Island Chairman’s Report 04 Interview with Matt Pope 38 Chief Executive’s Report 06 Jersey: Ice Age Island Shaping our Future 12 Exhibition Discoveries & Highlights 40 Jersey Heritage Headlines 14 Reminiscence 42 Coin Hoard - The Final Days 16 Community 46 The Neolithic Longhouse 20 Events & Education 48 Archives & Collections Online 26 Collections Abroad 52 Archive Case Studies 30 Edmund Blampied 1. Case Study - Worldwide Links Pencil Paint & Print 54 Australia 31 SMT & Board 56 2. Case Study - Volunteers at Sponsors & Patrons 58 Jersey Archive 32 Staff & Volunteers 60 3. Case Study - Talks and Tours 33 Bergerac’s Island - Jersey in the 4. Case Study - House History 1980s 62 Research 34 Love Your Castle 64 Heritage Lets 36 Membership 66 02 | 2016/2017 ANNUAL REVIEW INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION Jersey Heritage is a local charity that protects and promotes the Island’s rich heritage and cultural environment. We aim to inspire people to nurture their heritage in order to safeguard it for the benefit and enjoyment of everyone. We are an independent organisation that receives an annual grant from the States of Jersey to support our running costs. Admission income from visitors and support from sponsors are also vital to keep us operating. We are responsible for the Island’s major historic sites, award-winning museums and public archives. We hold collections of artefacts, works of art, documents, specimens and information relating to Jersey’s history, culture and environment. -

The Irish National Land League 1879-1881

THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY bis 3Vr '4 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/irishnationallanOOjenn THE IRISH NATIONAL LAND LEAGUE 1879 - 1881 BV WALTER WILSON JENNINGS THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS IN HISTORY COLLEGE OF LIBERAL A UTS AND SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1915 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 191 THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY ENTITLED IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF i.c^^^. ^ £. Instructor in Charge APPROVED: HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I Historical Sketch - the Remote Background: Elizabeth's system of colonization - Sir Charles Coote - Cromwell - Charles II - William III - Condi- tions in Ireland - Famine of 1847 and 1848 - Land Act 1 CHAPTER II Certain Conditions in Ireland. 1879-1881: Geography of Ireland - Population - Occupations - Products - Famine of 1879 - Land owners and their power - Evictions - Proposed remedies - Actual emigra- tion - Charity - Help from the United States - Relief committees - Duchess of Marlborough's Fund - Mansion— 9 CHAPTER III Organization. Ob.iects. and Methods of the Land League: Founding of the League - Support - Leaders and members - Executive meetings - Objects - Parnell's early plan - MasB meetings - Navan - Gurteen - Balla - Irishtown - Keash - Ennis - Ballybricken - Feenagh - Dublin demonstration - Dungarven local convention - General convention at Dublin - Newspapers - Frustra- tion of sales - Reinstatements - Boycotting - Some 22 CHAPTER -

Agrarian Reform in Eighteenth -Century Denmark

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers from the University Studies series (The University of Nebraska) University Studies of the University of Nebraska 1977 Agrarian Reform in Eighteenth -Century Denmark Lawrence J. Baack Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/univstudiespapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Studies of the University of Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers from the University Studies series (The University of Nebraska) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. new senes no. 56 University of Nebraska Studies 1977 Agrarian Reform in Eighteenth-Century Denmark The University of Nebraska The Board of Regents JAMES H. MOYLAN ROBERT L. RAUN chairman EDWARD SCHWARTZKOPF CHRISTINE L. BAKER STEVEN E. SHOVERS KERMIT HANSEN ROBERT G. SIMMONS, JR. ROBERT R. KOEFOOT, M.D. KERMIT WAGNER WILLIAM J. MUELLER WILLIAM F. SWANSON ROBERT J. PROKOP, M.D. corporation secretary The President RONALD W. ROSKENS The Chancellor, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Roy A. YOUNG Committee on Scholarly Publications GERALD THOMPSON DAVID H. GILBERT chairman executive secretary JAMES HASSLER KENNETH PREUSS HENRY F. HOLTZCLAW ROYCE RONNING ROBERT KNOLL Lawrence J. Baack Agrarian Reform in Eighteenth-Century Denmark university of nebraska studies : new series no. 56 published by the university at lincoln: 1977 For my mother. Frieda Baack Copyright © 1977 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 77-78548 UN ISSN 0077-6386 Manufactured in the United States of America Contents Preface vii Agrarian Reform in Eighteenth-Century Denmark 1 Notes 29 Acknowledgments 45 Preface AGRARIAN REFORM can be one of the most complex tasks of gov ernment. -

Tenant-Right in Nineteenth-Century Ireland Author(S): Timothy W

Economic History Association Bonds without Bondsmen: Tenant-Right in Nineteenth-Century Ireland Author(s): Timothy W. Guinnane and Ronald I. Miller Source: The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 56, No. 1 (Mar., 1996), pp. 113-142 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Economic History Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2124021 Accessed: 01/11/2010 12:25 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=cup. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Cambridge University Press and Economic History Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Economic History. -

Un Livret D'chansons Et D'gammes Entouor Jèrri, Not' Siez-Nous a Booklet of Songs and Activities About Jersey, Our Home Jèrri Chîn' Et Là Jersey Here and There

Un livret d'chansons et d'gammes entouor Jèrri, not' siez-nous A booklet of songs and activities about Jersey, our home Jèrri chîn' et là Jersey here and there prépathé par L'Office du Jèrriais http://www.jerriais.org.je/ Publié en 2012 par lé Dêpartément pouor l'Êducâtion, l'Sport et la Tchultuthe PO Box 142 Jèrri JE4 8QJ © L's Êtats d'Jèrri / The States of Jersey This book contains songs and activities to accompany lessons in Jersey Studies. Each song sets a theme for aspects of Jersey's culture, nature, geography, history and economy, and each lesson includes information, quizzes and games to support the classroom activities. The songs and quizzes can also be used outside Jersey Studies lessons. 1 Cont'nu - Contents 2 Chant d'Jèrri song - Jèrriais words by Geraint Jennings, music by Daniel Bourdelès 3 Island Song song - English words by Geraint Jennings, music by Daniel Bourdelès 4 Lesson 1: Les pliaiches et les langues - Places and languages 6 Tandi qué bouôn mathinnyi bait song - Jèrriais words by Augustus Asplet Le Gros (1840-1877), music by Alfred Amy (1867-1936) 7 Time and tide wait for no man English translation of song 8 Lesson 2: La mé et la grève - The sea and the beach 10 J'ai pèrdu ma femme traditional Jersey folksong 11 I lost my wife English translation of song 12 Lesson 3: Des cliôsées d'mangi - Fields full of food 14 Jean, gros Jean traditional Jersey folksong 15 John, fat John English translation of song 16 Lesson 4: Les fricots et les touristes - Meals and tourists 18 L'Île Dé Jèrri Jèrriais words to song (author unknown) 19 The Island of Jersey song in English - words and music by George Ware (1829-1895) 20 Lesson 5: Les sou et les neunméthos - Money and numbers 22 Man bieau p'tit Jèrri Jèrriais words to song by Frank Le Maistre (1910- 2002) 23 Beautiful Jersey song in English - words and music by Lindsay Lennox (d. -

THE BRITISH CHANNEL ISLANDS UNDER GERMAN OCCUPATION ‒ 00 Channel Prelims Fp Change 8/4/05 11:31 Am Page Ii

00 Channel prelims fp change 8/4/05 11:31 am Page i THE BRITISH CHANNEL ISLANDS UNDER GERMAN OCCUPATION ‒ 00 Channel prelims fp change 8/4/05 11:31 am Page ii Maurice Gould attempted to escape from Jersey with two teenage friends in a small boat in May . Aged only , he was caught and imprisoned in Jersey, then moved to Fresne prison near Paris before being transferred to SS Special Camp Hinzert. Brutally mistreated, Maurice Gould died in the arms of his co-escapee Peter Hassall in October . Initially buried in a German cemetery surrounded by SS graves, his remains were repatriated to Jersey through the efforts of the Royal British Legion in , were he was reinterred with full honours. 00 Channel prelims fp change 8/4/05 11:31 am Page iii THE BRITISH CHANNEL ISLANDS UNDER GERMAN OCCUPATION ‒ Paul Sanders SOCIETE JERSIAISE JERSEY HERITAGE TRUST 00 Channel prelims fp change 8/4/05 11:31 am Page iv First published by Jersey Heritage Trust Copyright © Paul Sanders ISBN --- The right of Paul Sanders to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act . All rights reserved. With the exception of quoting brief passages for the purpose of review, no part of this publication may be recorded, reproduced or transmitted by any means, including photocopying, without written permission from the publisher. Printed in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd., King’s Lynn 00 Channel prelims fp change 8/4/05 11:31 am Page v Mr F L M Corbet MEd FRSA Sir Peter Crill KBE Mr D G Filleul OBE Mr W M Ginns MBE Mr J Mière Mr R W Le Sueur Jurat A Vibert 00 Channel prelims fp change 8/4/05 11:31 am Page vi The Jersey Heritage Trust and the Société Jersiaise are most grateful to the following for providing financial support for the project. -

Jersey Studies Notes

1 2 This booklet contains supplementary material and notes to accompany Jèrri chîn' et là - the booklet of songs and activities for Jersey Studies, as well as the specially recorded songs. There are some additional wordsearches, explanations and context, which can be used to enhance the course, or as a resource collection for projects and lessons which touch on the themes introduced in Jersey Studies. There are literal translations into English of the Jèrriais song lyrics that do not have literal translations in Jèrri chîn' et là. 1 Cont'nu - Contents 2 Lesson 1: Les pliaiches et les langues - Places and languages 4 Lesson 2: La mé et la grève - The sea and the beach 6 Lesson 3: Des cliôsées d'mangi - Fields full of food 8 Lesson 4: Les fricots et les touristes - Meals and tourists 10 Lesson 5: Les sou et les neunméthos - Money and numbers 14 Lesson 6: Les sŷmboles dé Jèrri - Jersey's symbols One Jersey is the largest of the Channel Islands with an area of 45 square miles (118.2 km2) and is situated 14 miles off the north-west coast of France and 85 miles from the south coast of England. Area of Jersey by Parish km2 Vergées Acres Percent of Island area St. Ouen 15 8,447 3,754 13 St. Brelade 12 7,318 2,984 11 Trinity 12 6,942 3,086 10 St. Peter 12 6,539 2,906 10 St. Martin 10 5,688 2,529 9 St. Lawrence 10 5,454 2,424 8 St. Helier 9 5,263 2,339 8 St.