Chocolate: Modern Science Investigates an Ancient Medicine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Happy Christmas to All Our Readers

R e p o r t e80p where r sold News and Views from around the area Volume 9 Issue 11 December 2017 www.milbornestandrew.org.uk/reporter facebook.com/MilborneReporter Happy Christmas to all our readers BERE REGIS MOT & SERVICE CENTRE TEL: 01929 472205 MOTs (No Re-test fee within 10 working days) SERVICING REPAIRS BRAKES EXHAUSTS COMPUTERISED DIAGNOSTICS LATEST EQUIPMENT FOR MOST MAKES AND MODELS OVER 30 YEARS’ EXPERIENCE IN THE MOTOR TRADE COURTESY CAR AVAILABLE Proprietor: Bill Greer Unit 1 Townsend Business Park Bere Regis, BH20 7LA (At rear of Shell Service Station) Disclaimer THE views expressed in the Reporter are not necessarily those of the editorial team. Also, please be aware that articles and photographs printed in the Reporter will be posted on our website and so are available for anyone to access. ‘Back in time for Christmas’ The Reporter is not responsible for the content of any COME and join us for our Christmas Concert at Puddletown Village Hall advertisement or material on websites advertised within this on Saturday, 9th December 2017 at 7.30pm. magazine. Featuring an eclectic mix of music including carols and Christmas Please note songs, you will also have the opportunity to join in with some Please ensure that your anti-virus software is up to date before traditional carols to get you in the festive spirit! e-mailing. Copy should be sent as a Word (or other) text file and do There will be a licensed bar and free Christmassy nibbles, a raffle and not embed pictures, logos, etc. into the document. -

Stear Dissertation COGA Submission 26 May 2015

BEYOND THE FIFTH SUN: NAHUA TELEOLOGIES IN THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES By ©Copyright 2015 Ezekiel G. Stear Submitted to the graduate degree program in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson, Santa Arias ________________________________ Verónica Garibotto ________________________________ Patricia Manning ________________________________ Rocío Cortés ________________________________ Robert C. Schwaller Date Defended: May 6, 2015! ii The Dissertation Committee for Ezekiel G. Stear certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: BEYOND THE FIFTH SUN: NAHUA TELEOLOGIES IN THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES ________________________________ Chairperson, Santa Arias Date approved: May 6, 2015 iii Abstract After the surrender of Mexico-Tenochtitlan to Hernán Cortés and his native allies in 1521, the lived experiences of the Mexicas and other Nahuatl-speaking peoples in the valley of Mexico shifted radically. Indigenous elites during this new colonial period faced the disappearance of their ancestral knowledge, along with the imposition of Christianity and Spanish rule. Through appropriations of linear writing and collaborative intellectual projects, the native population, in particular the noble elite sought to understand their past, interpret their present, and shape their future. Nahua traditions emphasized balanced living. Yet how one could live out that balance in unknown times ahead became a topic of ongoing discussion in Nahua intellectual communities, and a question that resounds in the texts they produced. Writing at the intersections of Nahua studies, literary and cultural history, and critical theory, in this dissertation I investigate how indigenous intellectuals in Mexico-Tenochtitlan envisioned their future as part of their re-evaluations of the past. -

Ice Cream Dreams Summertime’S Most Perfect Comfort Food

The Chronicle-News Trinidad, Colorado Wednesday, Aug. 28, 2019 Page 3 Ice Cream Dreams Summertime’s most perfect comfort food Catherine J. Moser with maraschino cherries on top. Of course, a Features Editor Neapolitan sundae with a generous dollop of The Chronicle-News whipped cream and crushed pecan sprinkles Ice Cream, Blackberries & Cookies is a pretty smashing combo as well. Who Join me, why don’t you, as we take a trip wouldn’t like that? Images by Metro Creative and Pixabay to the wonderful world of ice cream. If there’s Actually, I love the idea of taking favorite anything that tastes better on a scorching hot cookies and making your own ice cream sand- summer night than ice cream, then I can’t wiches, too. Keebler’s Pecan Sandies make If any kind of real celebration is in the of- cial. Remember to keep cones in the pantry think of what that could possibly be. Ice cream incredible treats with any kind of ice cream fering, then an ice cream cake can be a stun- and surprise everyone in your gang with an is the perfect cold comfort food to treat your- squished in between them. Now, you can ab- ning hit for the event. Pound cake is particu- ice cream cone supper some weeknight — just self to when it’s blistering outside, you’re try- solutely bake your own sandies or any other larly versatile and delicious when it comes for fun. After eating a few scoops of delicious ing desperately to cool down and your appetite kind of cookie that you like, but during the to cutting and layering in between ice cream coldness smooshed into a crunchy cone, the has died. -

THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE, 2Nd MARCH 1982 327

THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE, 2nd MARCH 1982 327 Hellerman Electric, Penny Close, Plymouth, Devon. Rael-Brook Limited, Warrington Road, Rainhill, Merseyside. Hetton Paper Company Limited, Hetton Lyons Industrial Estate, Ranco Controls Limited, Dunmere Road, Bodmin and Newnham Hetton le Hole. Industrial Estate, Plymouth. Hotpoint Limited, Conwy Road, Llandudno Junction, Gwynedd. K. Raymakers & Sons Limited, Alma Mill, Wyre Street, Padiham, Howmet Turbine Components Corporation, Misco European Burnley. Division, Kestrel Way, Exeter. Rigby Metal Components Limited, Rawfotds Mill, Bradford Road, Huddersfield Fine Worsteds Limited, Bankfield Mills, Kirkheaton, Cleckheaton, West Yorkshire. Huddersfield. Robirch Limited, Mosley Street, Burton-on-Trent, Staffs. ICI, Paints Division, Slough. Romix Foods Limited, Locket Road, Ashton-in-Makerfield. Imco Plastics Limited, Imco Works, Beckery New Road, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh an'd Associated Hospitals, Royal Glastonbury, Somerset. Infirmary, Lauriston Place, Edinburgh. George Ingham & Company Limited, Prospect Mill, Stainland, Royal Ordnance Factory, Chorley. Greetland, Halifax. Samuel Courtaulds and Company Limited, Bedford New Mill, Leigh. Johnson & Johnson Limited, Airebank Mill, Gargrave, Skipton. R. P. Scherer Limited, Bath Road, Slough. John Player and Sons (Imperial Tobacco Limited t/a), No. 3 Factory, Scottish & Newcastle Breweries Limited, High Speed Canning Line, Radford Road, Nottingham and Horizon Factory, Thane Road, Viewforth, Edinburgh. Nottingham and Horizon Factory, Nottingham. Sealed Motor Construction Company Limited, Bristol Road, Kerr Electrical Limited, Lynedoch Industrial Estate and Pottery Bridgwater. Street, Greenock. Securon (Amersham) Limited, Winchmore Hill, Amersham, Bucks. Kingston Spinners (Scotland) Limited, Glasgow Road, Sanquhar, Senior Services Limited, Virginia House, Don Street, Middleton. Dumfries. SERCK Audo Valves, Newport Works, Audley Road, Newport. Klynton Davis Limited, Rangemore Street, Burton-on-Trent. Silentnight Limited, P.O. -

Around Five Kilometres/Three Miles) Will Take Approximately 90 Minutes, Or a Further 40 Minutes If You Choose to Do the Full Racecourse Circuit

This walk (around five kilometres/three miles) will take approximately 90 minutes, or a further 40 minutes if you choose to do the full racecourse circuit. It explores the southern stretch of the River Ouse in York. The commentary considers the impact of the river on the development of the City, the redevelopment of the iconic Terry’s Chocolate Works, and the importance of horse racing. It is full of variety, and includes elements of geography and geology as well as much about the history of the area. We have designed the walk to start at the Millennium Bridge, on the west side of the River Ouse, but you can start it at any point. The starting point is easily reached from the city centre on foot or bicycle, or the 11, 21 and 26 buses travel from the railway station along Bishopthorpe Road. If coming by car, you can park free on Campleshon Road or Knavesmire Road. For some background, follow this link for the Ordnance Survey map published in 1853 (https://maps.nls.uk/view/102344815) you will see that this area was almost all fields at this time. Then look at the Ordnance Survey map published in 1932 (https://maps.nls.uk/view/100945733) where you will see many changes. Perhaps the best place for a drink and something to eat is the Winning Post on Bishopthorpe Road (just a couple of hundred metres north of the junction with Campleshon Road). This walk has created by John Stevens for Clements Hall Local History Group. PLEASE NOTE This walk is unsuitable for wheelchair users and those with mobility problems, as it involves stiles, sometimes wet and/or muddy patches, and ducking under the racecourse rails. -

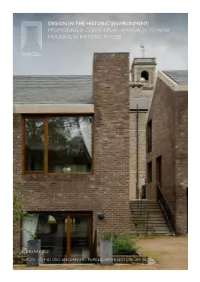

Design in the Historic Environment: Promoting a Contextual Approach to New Housing in Historic Places

DESIGN IN THE HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT: PROMOTING A CONTEXTUAL APPROACH TO NEW HOUSING IN HISTORIC PLACES FEBRUARY 2021 REPORT TO HISTORIC ENGLAND BY PURCELL ARCHITECTURE LIMITED Will Holborow On behalf of Purcell® 104 Gloucester Green, Oxford, OX1 2BU 240820 [email protected] www.purcelluk.com Purcell asserts its moral rights to be identified as the author of this work under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Purcell® is the trading name of Purcell Architecture Ltd. © Purcell 2021 Cover photo: Wildernesse House © Historic England Archive DESIGN IN THE HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT: PROMOTING A CONTEXTUAL APPROACH TO NEW HOUSING IN HISTORIC PLACES CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 04 1.1 Background 04 1.2 Aim and Objective of the Report 04 1.3 Project Commissioning 04 1.4 Project Methodology 04 1.5 Historic England’s Role in Placeshaping 05 2.0 THE STRATEGIC CONTEXT 07 2.1 Government Planning Policy 07 2.2 White Paper: Planning for the future 07 2.3 Design Panels 07 2.4 Design Codes 08 2.5 National Design Leadership 08 2.6 Potential Role for Historic England 08 3.0 ANALYSIS OF EXISTING DESIGN GUIDANCE 09 3.1 Overview of Current Guidance 09 3.2 Principles of Contextual Design 10 3.3 Historic England’s Online Offer: Description and Analysis 10 3.4 Historic England’s Published Guidance 14 3.5 Recent Advocacy Documents 16 3.6 Design Toolkits 16 3.7 Local Design Guidance 16 3.8 Conclusions 17 4.0 ORGANISATIONS PROMOTING DESIGN QUALITY 18 5.0 SELECTION OF CASE STUDIES 19 6.0 RECOMMENDATIONS 20 APPENDICES 21 Appendix A: Table of Related Publications 21 Appendix B1: Table of Case Studies 26 Appendix B2: Case studies shortlisted and photographed but not selected 28 Appendix B3: Case studies shortlisted but not selected or photographed 29 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND standards. -

British Construction Industry Awards 2018 Celebrating the Very Best in Construction and Engineering

British Construction Industry Awards 2018 Celebrating the very best in construction and engineering The BCI Awards are Brought to you by the longest standing, most rigorously judged and highly prized in the United Kingdom construction sector 2018 Judges Initiative Chief technical Peter Molyneux Keith Waller ICE officer, Mott Major roads director, Senior advisor, Steve Fox category MacDonald and Transport for the Infrastructure & Chief executive, judges Project 13 North Projects Authority Bam Nuttall Hugh Ferguson Chris Newsome Briony Wickenden Mark Hansford Hero Bennett Former deputy Executive director, Head of training, Editor, NCE Sustainability director general, Anglian Water Ceca Keith Howells consultant, ICE Alison Nicholl Chairman, Max Fordman Steve Fink Director, Mott MacDonald Kelly Bradley Project Phase 1 health, safety Constructing category Darren James Legacy and & security director, Excellence Infrastructure community HS2 Ltd Jerry Pullinger judges managing director, investment manager, Bill Hewlett Principal engineer, Costain Tideway Technical director, Kier Professional Ken Allison Isabel Liu Fay Bull Costain Group Services Director allocation & Board member, Regional director Katherine Ibbotson Alasdair Reisner asset management, Transport Focus – water, UK&I, Carbon planning Chief executive, Environment Agency John Lorimer Aecom manager, Civil Engineering Emily Ashwell Chairman, BIM Volker Buscher Environment Contractors Associate Editor, Academy Director, global Agency Association (Ceca) New Civil Engineer Kate Mavor & -

The Devil and the Skirt an Iconographic Inquiry Into the Prehispanic Nature of the Tzitzimime

THE DEVIL AND THE SKIRT AN ICONOGRAPHIC INQUIRY INTO THE PREHISPANIC NATURE OF THE TZITZIMIME CECELIA F. KLEIN U.C.L.A. INTRODUCTION On folio 76r of the colonial Central Mexican painted manuscript Codex Magliabechiano, a large, round-eyed figure with disheveled black hair and skeletal head and limbs stares menacingly at the viewer (Fig. 1a). 1 Turned to face us, the image appears ready to burst from the cramped confines of its pictorial space, as if to reach out and grasp us with its sharp talons. Stunned by its gaping mouth and its protruding tongue in the form of an ancient Aztec sacrificial knife, viewers today may re- coil from the implication that the creature wants to eat them. This im- pression is confirmed by the cognate image on folio 46r of Codex Tudela (Fig. 1b). In the less artful Tudela version, it is blood rather than a stone knife that issues from the frightening figures mouth. The blood pours onto the ground in front of the figures outspread legs, where a snake dangles in the Magliabecchiano image. Whereas the Maglia- bechiano figure wears human hands in its ears, the ears of the Tudela figure have been adorned with bloody cloths. In both manuscripts, long assumed to present us with a window to the prehispanic past, a crest of paper banners embedded in the creatures unruly hair, together with a 1 This paper, which is dedicated to my friend and colleague Doris Heyden, evolved out of a talk presented at the 1993 symposium on Goddesses of the Western Hemisphere: Women and Power which was held at the M.H. -

Spring Fling 2017 Auction Catalog

SPRING FLING 2017 AUCTION CATALOG You’ll find the complete listing of all items included in last year’s auction. In several instances, multiples of the same item were donated – duplicates are not included in this list. Items are grouped in these Sections Arts & Entertainment ......................................................................................................... 2 Classes For Parents ......................................................................................................... 6 Electronics & Home .......................................................................................................... 7 Fashion, Jewelry, Accessories, & Home .......................................................................... 9 Food & Wine ................................................................................................................... 11 For Kids .......................................................................................................................... 18 Gift Cards ........................................................................................................................ 18 Health & Fitness ............................................................................................................. 19 Kids Classes & Parties ................................................................................................... 22 Kids Other ....................................................................................................................... 29 Kids Summer Camp -

Aztec Human Sacrifice As Entertainment? the Physio-Psycho- Social Rewards of Aztec Sacrificial Celebrations

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2017 Aztec Human Sacrifice as Entertainment? The Physio-Psycho- Social Rewards of Aztec Sacrificial Celebrations Linda Jane Hansen University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Hansen, Linda Jane, "Aztec Human Sacrifice as Entertainment? The Physio-Psycho-Social Rewards of Aztec Sacrificial Celebrations" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1287. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1287 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. AZTEC HUMAN SACRIFICE AS ENTERTAINMENT? THE PHYSIO-PSYCHO-SOCIAL REWARDS OF AZTEC SACRIFICIAL CELEBRATIONS ___________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the University of Denver and the Iliff School of Theology Joint PhD Program University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Linda Prueitt Hansen June 2017 Advisor: Dr. Annabeth Headrick ©Copyright by Linda Prueitt Hansen 2017 All Rights Reserved Author: Linda Prueitt Hansen Title: Aztec Human Sacrifice as Entertainment? The Physio-Psycho-Social Rewards of Aztec Sacrificial Celebrations Advisor: Dr. Annabeth Headrick Degree Date: June 2017 ABSTRACT Human sacrifice in the sixteenth-century Aztec Empire, as recorded by Spanish chroniclers, was conducted on a large scale and was usually the climactic ritual act culminating elaborate multi-day festivals. -

ED368537.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 368 537 RC 019 614 AUTHOR Reagan, Timothy TITLE Developing "Face and Heart" in the Time of the Fifth Sun: An Examination of Aztec Education. PUB DATE Apr 94 NOTE 20p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association (New Orleans, LA, April 4-8, 1994). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indian Education; American Indian History; Child Rearing; *Educational History; *Educational Practices; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; *Latin American History; Religion; Socialization IDENTIFIERS *Aztec (People); *Mexico ABSTRACT This paper provides a general overview of Aztec education as it existed when the Spanish arrived in 1519. A brief history traces the rise of the Aztecs from lower-class squatters and mercenaries in the Valley of Mexico to the rulers of a loosely structured "empire" consisting of some 15 million people. Aztec society was highly stratified, but higher rank carried with it higher expectations of moral responsibility and correct conduct. The foundations of society were a religion that ensured the continued existence of the cosmos through the shedding of human blood, and warfare that provided both the blood of warriors and sacrificial victims. Aztec education aimed to promote socially appropriate behavior and instill core values such as self-control and courage in the face of death. Young children learned their parents' daily tasks, learned to tolerate hunger and discomfort, and were punished for inappropriate behavior. At ages 12-15, both boys and girls attended a formal school maintained by their kinship group, where they received religious and cultural education. -

A Comparison of Contributions from the Aztec Cities of Tlatelolco and Tenochtitlan to the Bird Chapter of the Florentine Codex

ISSN: 1870-7459 Haemig, P.D. Huitzil, Revista Mexicana de Ornitología DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.28947/hrmo.2018.19.1.304 ARTÍCULO ORIGINAL A comparison of contributions from the Aztec cities of Tlatelolco and Tenochtitlan to the bird chapter of the Florentine Codex Una comparación de las contribuciones de las ciudades aztecas de Tlatelolco y Tenochtitlan al capítulo de aves del Códice Florentino Paul D. Haemig1 Abstract The Florentine Codex is a Renaissance-era illuminated manuscript that contains the earliest-known regional work on the birds of México. Its Nahuatl language texts and scholia (the latter later incorporated into its Spanish texts) were written in the 1560s by Bernardino de Sahagún’s research group of elite native Mexican scholars in collaboration with Aztecs from two cities: Tla- telolco and Tenochtitlan. In the present study, I compared the contributions from these two cities and found many differences. While both cities contributed accounts and descriptions of land and water birds, those from Tlatelolco were mainly land birds, while those from Tenochtitlan were mainly water birds. Tlatelolco contributed over twice as many bird accounts as Tenochtitlan, and supplied the only information about medicinal uses of birds. Tenochtitlan peer reviewed the Tlatelolco bird accounts and improved many of them. In addition, Tenochtitlan contributed all information on bird abundance and most information about which birds were eaten and not eaten by humans. Spanish bird names appear more frequently in the Aztec language texts from Tenochtitlan. Content analysis of the Tenochtitlan accounts suggests collaboration with the water folk Atlaca (a prehistoric la- custrine culture) and indigenous contacts with Spanish falconers.