How to Think About Science.” Our Guest Is Brian Wynne of Lancaster University in the North of England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

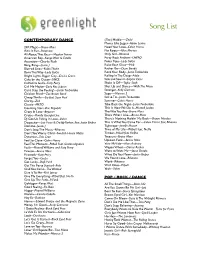

Front of House Master Song List

CURRENT ROTATION CONTEMPORARY DANCE Love on Top – Beyoncé 24K Magic – Bruno Mars Moves Like Jagger – Maroon 5 All About That Bass – Meghan Trainor Mr. Saxobeat – Alexandra Stan All of Me – John Legend No One – Alicia Keys American Boy – Estelle & Kanye West OMG – Usher Applause – Lady Gaga One Kiss – Calvin Harris, Dua Lipa Bang Bang – Jessie J, Ariana Grande, Nicki Minaj Only Girl (in the World) – Rihanna Blurred Lines – Robin Thicke On the Floor – Jennifer Lopez Boom Clap – Charlie XCX Party In The USA – Miley Cyrus Born This Way – Lady Gaga Party Rock Anthem – LMFAO Break Free – Ariana Grande Perm – Bruno Mars California Gurls – Katy Perry Poker Face – Lady Gaga Cake By The Ocean – DNCE Raise Your Glass – Pink Call Me Maybe – Carly Rae Jepsen Rather Be – Clean Bandit ft. Jess Glynn Can’t Feel My Face – The Weeknd Roar – Katy Perry Can’t Hold Us – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Rock Your Body – Justin Timberlake Can’t Stop The Feeling – Justin Timberlake Rolling in the Deep – Adele Cheap Thrills – Sia Safe and Sound – Capital Cities Cheerleader – OMI Sexy Back – Justin Timberlake Closer – Chainsmokers ft. Halsey Shake It Off – Taylor Swift Club Can’t Handle Me – Flo Rida Shape of You – Ed Sheeran Confident – Demi Lovato Shut Up and Dance With Me – Walk the Moon Counting Stars – OneRepublic Single Ladies – Beyoncé Crazy – Gnarls Barkley Sugar – Maroon 5 Crazy In Love / Funk Medley – Beyoncé, others Suit & Tie – Justin Timberlake Despacito – Luis Fonsi ft. Justin Bieber Take Back the Night – Justin Timberlake DJ Got Us Falling in Love Again – Usher That’s What I Like – Bruno Mars Don’t Stop the Music – Rihanna There’s Nothing Holding Me Back – Shawn Mendez Domino – Jessie J This Is What You Came For – Calvin Harris ft. -

Third Wave of Science Studies: Studies of Expertise and Experience H.M

Social Studies of Science http://sss.sagepub.com/ The Third Wave of Science Studies: Studies of Expertise and Experience H.M. Collins and Robert Evans Social Studies of Science 2002 32: 235 DOI: 10.1177/0306312702032002003 The online version of this article can be found at: http://sss.sagepub.com/content/32/2/235 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Social Studies of Science can be found at: Email Alerts: http://sss.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://sss.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav >> Version of Record - Apr 1, 2002 What is This? Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF RHODE ISLAND LIBRARY on December 9, 2013 DISCUSSION PAPER ABSTRACT Science studies has shown us why science and technology cannot always solve technical problems in the public domain. In particular, the speed of political decision-making is faster than the speed of scientific consensus formation. A predominant motif over recent years has been the need to extend the domain of technical decision-making beyond the technically qualified ´elite, so as to enhance political legitimacy. We argue, however, that the ‘Problem of Legitimacy’ has been replaced by the ‘Problem of Extension’ – that is, by a tendency to dissolve the boundary between experts and the public so that there are no longer any grounds for limiting the indefinite extension of technical decision-making rights. We argue that a Third Wave of Science Studies – Studies of Expertise and Experience (SEE) – is needed to solve the Problem of Extension. -

1 Ethers, Religion and Politics In

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE Ethers, religion and politics in late-Victorian physics: beyond the Wynne thesis AUTHORS Noakes, Richard JOURNAL History of Science DEPOSITED IN ORE 16 June 2008 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/30065 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication ETHERS, RELIGION AND POLITICS IN LATE-VICTORIAN PHYSICS: BEYOND THE WYNNE THESIS RICHARD NOAKES 1. INTRODUCTION In the past thirty years historians have demonstrated that the ether of physics was one of the most flexible of all concepts in the natural sciences. Cantor and Hodge’s seminal collection of essays of 1981 showed how during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries British and European natural philosophers invented a range of ethers to fulfil diverse functions from the chemical and physiological to the physical and theological.1 In religious discourse, for example, Cantor identified “animate” and spiritual ethers invented by neo-Platonists, mystics and some Anglicans to provide a mechanism for supporting their belief in Divine immanence in the cosmos; material, mechanistic and contact-action ethers which appealed to atheists and Low Churchmen because such media enabled activity in the universe without constant and direct Divine intervention; and semi-spiritual/semi-material ethers that appealed to dualists seeking a mechanism for understanding the interaction of mind and matter. 2 The third type proved especially attractive to Oliver Lodge and several other late-Victorian physicists who claimed that the extraordinary physical properties of the ether made it a possible mediator between matter and spirit, and a weapon in their fight against materialistic conceptions of the cosmos. -

Bad Habit Song List

BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song 4 Non Blondes Whats Up Alanis Morissette You Oughta Know Alanis Morissette Crazy Alanis Morissette You Learn Alanis Morissette Uninvited Alanis Morissette Thank You Alanis Morissette Ironic Alanis Morissette Hand In My Pocket Alice Merton No Roots Billie Eilish Bad Guy Bobby Brown My Prerogative Britney Spears Baby One More Time Bruno Mars Uptown Funk Bruno Mars 24K Magic Bruno Mars Treasure Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey Christina Aguilera Fighter Corey Hart Sunglasses at Night Cyndi Lauper Time After Time David Guetta Titanium Deee-Lite Groove Is In The Heart Dishwalla Counting Blue Cars DNCE Cake By the Ocean Dua Lipa One Kiss Dua Lipa New Rules Dua Lipa Break My Heart Ed Sheeran Blow BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song Elle King Ex’s & Oh’s En Vogue Free Your Mind Eurythmics Sweet Dreams Fall Out Boy Beat It George Michael Faith Guns N’ Roses Sweet Child O’ Mine Hailee Steinfeld Starving Halsey Graveyard Imagine Dragons Whatever It Takes Janet Jackson Rhythm Nation Jessie J Price Tag Jet Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jewel Who Will Save Your Soul Jo Dee Messina Heads Carolina, Tails California Jonas Brothers Sucker Journey Separate Ways Justin Timberlake Can’t Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Say Something Katy Perry Teenage Dream Katy Perry Dark Horse Katy Perry I Kissed a Girl Kings Of Leon Sex On Fire Lady Gaga Born This Way Lady Gaga Bad Romance Lady Gaga Just Dance Lady Gaga Poker Face Lady Gaga Yoü and I Lady Gaga Telephone BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song Lady Gaga Shallow Letters to Cleo Here and Now Lizzo Truth Hurts Lorde Royals Madonna Vogue Madonna Into The Groove Madonna Holiday Madonna Border Line Madonna Lucky Star Madonna Ray of Light Meghan Trainor All About That Bass Michael Jackson Dirty Diana Michael Jackson Billie Jean Michael Jackson Human Nature Michael Jackson Black Or White Michael Jackson Bad Michael Jackson Wanna Be Startin’ Something Michael Jackson P.Y.T. -

Download Report 2010-12

RESEARCH REPORt 2010—2012 MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Cover: Aurora borealis paintings by William Crowder, National Geographic (1947). The International Geophysical Year (1957–8) transformed research on the aurora, one of nature’s most elusive and intensely beautiful phenomena. Aurorae became the center of interest for the big science of powerful rockets, complex satellites and large group efforts to understand the magnetic and charged particle environment of the earth. The auroral visoplot displayed here provided guidance for recording observations in a standardized form, translating the sublime aesthetics of pictorial depictions of aurorae into the mechanical aesthetics of numbers and symbols. Most of the portait photographs were taken by Skúli Sigurdsson RESEARCH REPORT 2010—2012 MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Introduction The Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (MPIWG) is made up of three Departments, each administered by a Director, and several Independent Research Groups, each led for five years by an outstanding junior scholar. Since its foundation in 1994 the MPIWG has investigated fundamental questions of the history of knowl- edge from the Neolithic to the present. The focus has been on the history of the natu- ral sciences, but recent projects have also integrated the history of technology and the history of the human sciences into a more panoramic view of the history of knowl- edge. Of central interest is the emergence of basic categories of scientific thinking and practice as well as their transformation over time: examples include experiment, ob- servation, normalcy, space, evidence, biodiversity or force. -

Greenlight's Complete Song List

Song List CONTEMPORARY DANCE (The) Middle—-Zedd Moves Like Jagger--Adam Levine 24K Magic—Bruno Mars Need Your Love--Calvin Harris Ain’t It Fun--Paramore No Roots—Alice Merton All About That Bass—Meghan Trainor Only Girl--Rihanna American Boy--Kanye West & Estelle Party Rock Anthem--LMFAO Attention—Charlie Puth Poker Face--Lady GaGa Bang, Bang—Jessie J Raise Your Glass—Pink Blurred Lines--Robin Thicke Rather Be—Clean Bandit Born This Way--Lady GaGa Rock Your Body--Justin Timberlake Bright Lights, Bigger City--Cee-Lo Green Rolling In The Deep--Adele Cake by the Ocean--DNCE Safe and Sound--Capitol Cities California Gurls--Katy Perry Shake It Off—Taylor Swift Call Me Maybe--Carly Rae Jepson Shut Up and Dance—Walk The Moon Can’t Stop the Feeling!—Justin Timberlake Stronger--Kelly Clarkson Chicken Fried—Zac Brown Band Sugar—Maroon 5 Cheap Thrills—Sia feat. Sean Paul Suit & Tie--Justin Timberlake Clarity--Zed Summer--Calvin Harris Classic--MKTO Take Back the Night--Justin Timberlake Counting Stars-One Republic This Is How We Do It--Montell Jordan Crazy In Love--Beyonce The Way You Are--Bruno Mars Cruise--Florida Georgia Line That’s What I Like—Bruno Mars DJ Got Us Falling In Love--Usher There’s Nothing Holdin’ Me Back—Shawn Mendes Despacito—Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee, feat. Justin Bieber This Is What You Came For—Calvin Harris feat. Rihanna Domino--Jessie J Tightrope--Janelle Monae Don’t Stop The Music--Rihanna Time of My Life—Pitbull feat. NeYo Don’t You Worry Child--Swedish House Mafia Timber--Pitbull feat. -

(OAS) and the Conference of Radiation Control Program Directors

1 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION + + + + + MEETING WITH THE ORGANIZATION OF AGREEMENT STATES (OAS) AND THE CONFERENCE OF RADIATION CONTROL PROGRAM DIRECTORS (CRCPD) + + + + + TUESDAY, APRIL 19, 2016 + + + + + ROCKVILLE, MARYLAND + + + + + The Commission met in the Commissioners’ Hearing Room at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, One White Flint North, 11555 Rockville Pike, at 9:30 a.m., Stephen G. Burns, Chairman, presiding. COMMISSION MEMBERS: STEPHEN G. BURNS, Chairman KRISTINE L. SVINICKI, Commissioner WILLIAM C. OSTENDORFF, Commissioner JEFF BARAN, Commissioner ALSO PRESENT: ROCHELLE BAVOL, Executive Assistant, Office of the Secretary of the Commission 2 MARGARET DOANE, General Counsel PARTICIPANTS: SHERRIE FLAHERTY, MHP, DC, Supervisor, Radioactive Materials Unity, Minnesota Department of Health (OAS Chair) WILLIAM IRWIN, SC.D., CHP, Program Chief, Radiological and Toxicological Sciences Program, Vermont Department of Health (CRCPD Chair) MATT MCKINLEY, Administrator, Radiation Health Branch, Kentucky Department for Public Health (OAS Chair- Elect) JARED THOMPSON, Program Manager, Radioactive Materials Program, Arkansas Department of Health (CRCPD Chair-Elect) MIKE WELLING, Director, Radioactive Materials Program, Virginia Department of Health (OAS Past Chair) 3 1 P R O C E E D I N G S 2 9:31 a.m. 3 CHAIRMAN BURNS: Okay. All right. Well, good 4 morning, everyone, and we want to welcome our representatives from 5 the Organization of Agreement States and the Conference of Radiation 6 Control Program Directors. -

Q&A REPORTING, INC. [email protected] Page 1

DISCLAIMER: This is NOT a certified or verbatim transcript, but rather represents only the context of the class or meeting, subject to the inherent limitations of realtime captioning. The primary focus of realtime captioning is general communication access and as such this document is not suitable, acceptable, nor is it intended for use in any type of legal proceeding. MICRC 06/30/21 9:00 am Meeting Captioned by Q&A Reporting, Inc., www.qacaptions.com >> CHAIR KELLOM: Good morning. As Chair of the Commission, I call this meeting of the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission to order at 9:00 a.m. This meeting is being live streamed at YouTube. For anyone in the public watching who would prefer to watch via a different platform than they are currently using, please visit our social media at Redistricting MI to find the link for viewing on YouTube. Our live stream today includes closed captioning. Closed captioning, ASL interpretation, and Spanish and Bengali and Arabic translation services will be provided for effective participation in this meeting. E-mail us at [email protected] for additional viewing options or details on accessing language translation services for this meeting. People with disabilities or needing other specific accommodations should also contact Redistricting at Michigan.gov. For purpose us of the public record, this meeting is also being transcribed, and those transcriptions will be made available and posted at Michigan.gov/MICRC along with the written public comment submissions. This meeting is being transcribed and posted on Michigan.gov and MICRC along with written public submissions. -

Tom Stoppard

Tom Stoppard: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Stoppard, Tom Title: Tom Stoppard Papers Dates: 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Extent: 149 document cases, 9 oversize boxes, 9 oversize folders, 10 galley folders (62 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this British playwright consist of typescript and handwritten drafts, revision pages, outlines, and notes; production material, including cast lists, set drawings, schedules, and photographs; theatre programs; posters; advertisements; clippings; page and galley proofs; dust jackets; correspondence; legal documents and financial papers, including passports, contracts, and royalty and account statements; itineraries; appointment books and diary sheets; photographs; sheet music; sound recordings; a scrapbook; artwork; minutes of meetings; and publications. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Language English. Arrangement Due to size, this inventory has been divided into two separate units which can be accessed by clicking on the highlighted text below: Tom Stoppard Papers--Series descriptions and Series I. through Series II. [Part I] Tom Stoppard Papers--Series III. through Series V. and Indices [Part II] [This page] Stoppard, Tom Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Series III. Correspondence, 1954-2000, nd 19 boxes Subseries A: General Correspondence, 1954-2000, nd By Date 1968-2000, nd Container 124.1-5 1994, nd Container 66.7 "Miscellaneous," Aug. 1992-Nov. 1993 Container 53.4 Copies of outgoing letters, 1989-91 Container 125.3 Copies of outgoing -

How to Plan Your Vermont Wedding

How to Plan Your Vermont Wedding Practical Tips & Honest Advice by Vermont Wedding Expert, Alison Ellis floralartvt.com Welcome to Vermont. Congratulations on your engagement! You’re getting married in Vermont which means you are a lover of the outdoors, a nature enthusiast, a hiker, a skier or rider, a college alum, a native-Vermonter or simply that you want to surround yourselves and your guests with a beautiful setting. VT is an incredible destination. My intention for putting these tips together for you is simple: Planning a wedding takes a lot of work & you’ve never done this before. This guide will help streamline your planning process…whether you’re planning from in-state or across the country. Here are 10 Essential Planning Tips based on over 14 years in the Vermont wedding industry. (I also speak from personal experience since my husband and I planned our own Vermont wedding in 2003.) I want to help set you on the right path & jumpstart your planning. You deserve the wedding of your dreams…so let’s get started. floralartvt.com #1 Location, location, location. Truly, your first step is to choose your venue. Your location determines so much about your wedding day. Do they provide tables? Have an in-house caterer? Each site has its own attributes & potential challenges so you need to lock down a date & place before you can do anything else. Visit your site around the time of year you plan to marry. You’ll see what’s in bloom, surrounding views, and whether there are any aspects of the environment that detract from the aesthetic. -

The Music Industry?

Contents 02!Forewords 04!Executive Summary 07!Data Comes of Age 24!DSP Dashboards 28!Data and the Charts 31!Practical Tips 34!Data Startups to Watch Forewords Geoff Taylor, chief executive of the BPI, and Kim Bayley, chief executive of ERA, on why big-data and analytics matter for labels, artists and digital 1 service providers alike Forewords Kim Bayley, CEO Geoff Taylor, CEO Entertainment Retailers Association BPI and BRIT Awards Much has been written about how digital music services including What powers the UK’s exceptional success in producing global hit records? Spotify, Amazon, Apple, Deezer and Google have helped return a music First of all, of course, the natural talent, open-mindedness and originality of industry whose decline once seemed terminal into growth again. our songwriters, producers and performers. But creating consistent commercial success also means relentless investment in A&R, an appetite But while digital services are proving their worth in terms of revenue, for risk-taking informed by years of experience and judgement, and their greatest contribution may yet turn out to be the vast quantities of innovative, expert marketing and promotion. data they generate about music fans’ preferences and listening habits. Increasingly, data, in all its forms – spanning metadata to big data – is Not only does this data allow them to hone their services, optimise playing a key role in shaping this process. As streaming comes to playlists and generate insights which could lead to new, value-added dominate music consumption, data is becoming a progressively more offerings, it is also potentially game-changing for the supply side of the important part of the process of producing and marketing music and, business, taking some guesswork out of what has always been a hit and arguably, one of the determinants of a song’s popularity. -

Tapra 2015 Conference Programme P a G E | 1 TABLE of CONTENTS

Conference 2015 Conference Programme 8th - 10th September 2015 PUBLISHERS AT TAPRA 2015 The following publishers will be present at the TaPRA 2015 Conference. Their display stands will be located in the Quandrangle Court where all refreshments and lunches will be served daily Manchester University Press Matthew Frost [email protected] Palgrave Macmillan Jenny McCall [email protected] Lucinda Knight [email protected] Bloomsbury Publishing Mark Dudgeon [email protected] Emily Hockley [email protected] Cambridge University Press Kerr Alexander [email protected] Routledge Marie Coffey [email protected] Claire Spence [email protected] Ben Piggott [email protected] Kate Edwards [email protected] Intellect [email protected] WELCOME TO TAPRA 2015 @ WORCESTER Last year we celebrated TaPRA @ 10 at Royal Holloway, this year we look forward to the next decade for TaPRA with our conference hosts at the University of Worcester. A record number of members booked early this year and we have a packed conference programme but, as always, there will be plenty of opportunities to meet old friends and make new connections with colleagues representing the rich and diverse research interests of our field. There are a number of ‘new’ things to note this year: a new Working Group, Performance and Science, has its first full meeting in Worcester, bringing the number of Working Groups to twelve, with a proposal for a thirteenth group, Asian Performance and Diaspora gathering to test the level of interest from the membership. Another initiative making its debut at Worcester is Research Matters, the first in a series of conference panels curated by TaPRA’s executive committee and designed to respond to issues of current importance to the wider research community.