Sedition in WWI Lesson Plan Central Historical Question: Were Critics Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 20 Ap® Focus & Annotated Chapter Outline Ap® Focus

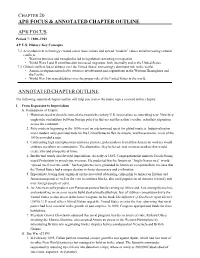

CHAPTER 20 AP® FOCUS & ANNOTATED CHAPTER OUTLINE AP® FOCUS Period 7: 1890–1945 AP U.S. History Key Concepts 7.2 A revolution in technology created a new mass culture and spread “modern” values amid increasing cultural conflicts. • Wartime tensions and xenophobia led to legislation restricting immigration. • World Wars I and II contributed to increased migration, both internally and to the United States. 7.3 Global conflicts led to debates over the United States’ increasingly dominant role in the world. • American expansionism led to overseas involvement and acquisitions in the Western Hemisphere and the Pacific. • World War I increased debates over the proper role of the United States in the world. ANNOTATED CHAPTER OUTLINE The following annotated chapter outline will help you review the major topics covered in this chapter. I. From Expansion to Imperialism A. Foundations of Empire 1. Historians used to describe turn-of-the-twentieth-century U.S. imperialism as something new. Now they emphasize continuities between foreign policy in this era and the nation’s earlier, relentless expansion across the continent. 2. Policymakers beginning in the 1890s went on a determined quest for global markets. Industrialization and a modern navy provided tools for the United States to flex its muscle, and the economic crisis of the 1890s provided a spur. 3. Confronting high unemployment and mass protests, policymakers feared that American workers would embrace socialism or communism. The alternative, they believed, was overseas markets that would create jobs and prosperity at home. 4. Intellectual trends also favored imperialism. As early as 1885, Congregationalist minister Josiah Strong urged Protestants to proselytize overseas. -

Espionage Act of 1917

Communication Law Review An Analysis of Congressional Arguments Limiting Free Speech Laura Long, University of Oklahoma The Alien and Sedition Acts, Espionage and Sedition Acts, and USA PATRIOT Act are all war-time acts passed by Congress which are viewed as blatant civil rights violations. This study identifies recurring arguments presented during congressional debates of these acts. Analysis of the arguments suggests that Terror Management Theory may explain why civil rights were given up in the name of security. Further, the citizen and non-citizen distinction in addition to political ramifications are discussed. The Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 are considered by many as gross violations of civil liberties and constitutional rights. John Miller, in his book, Crisis in Freedom, described the Alien and Sedition Acts as a failure from every point of view. Miller explained the Federalists’ “disregard of the basic freedoms of Americans [completed] their ruin and cost them the confidence and respect of the people.”1 John Adams described the acts as “an ineffectual attempt to extinguish the fire of defamation, but it operated like oil upon the flames.”2 Other scholars have claimed that the acts were not simply unwise policy, but they were unconstitutional measures.3 In an article titled “Order vs. Liberty,” Larry Gragg argued that they were blatantly against the First Amendment protections outlined only seven years earlier.4 Despite popular opinion that the acts were unconstitutional and violated basic civil liberties, arguments used to pass the acts have resurfaced throughout United States history. Those arguments seek to instill fear in American citizens that foreigners will ultimately be the demise to the United States unless quick and decisive action is taken. -

The War to End All Wars. COMMEMORATIVE

FALL 2014 BEFORE THE NEW AGE and the New Frontier and the New Deal, before Roy Rogers and John Wayne and Tom Mix, before Bugs Bunny and Mickey Mouse and Felix the Cat, before the TVA and TV and radio and the Radio Flyer, before The Grapes of Wrath and Gone with the Wind and The Jazz Singer, before the CIA and the FBI and the WPA, before airlines and airmail and air conditioning, before LBJ and JFK and FDR, before the Space Shuttle and Sputnik and the Hindenburg and the Spirit of St. Louis, before the Greed Decade and the Me Decade and the Summer of Love and the Great Depression and Prohibition, before Yuppies and Hippies and Okies and Flappers, before Saigon and Inchon and Nuremberg and Pearl Harbor and Weimar, before Ho and Mao and Chiang, before MP3s and CDs and LPs, before Martin Luther King and Thurgood Marshall and Jackie Robinson, before the pill and Pampers and penicillin, before GI surgery and GI Joe and the GI Bill, before AFDC and HUD and Welfare and Medicare and Social Security, before Super Glue and titanium and Lucite, before the Sears Tower and the Twin Towers and the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building, before the In Crowd and the A Train and the Lost Generation, before the Blue Angels and Rhythm & Blues and Rhapsody in Blue, before Tupperware and the refrigerator and the automatic transmission and the aerosol can and the Band-Aid and nylon and the ballpoint pen and sliced bread, before the Iraq War and the Gulf War and the Cold War and the Vietnam War and the Korean War and the Second World War, there was the First World War, World War I, The Great War, The War to End All Wars. -

World War I - on the Homefront

World War I - On the Homefront Teacher’s Guide Written By: Melissa McMeen Produced and Distributed by: www.MediaRichLearning.com AMERICA IN THE 20TH CENTURY: WORLD WAR I—ON THE HOMEFRONT TEACHER’S GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Materials in Unit .................................................... 3 Introduction to the Series .................................................... 3 Introduction to the Program .................................................... 3 Standards .................................................... 4 Instructional Notes .................................................... 5 Suggested Instructional Procedures .................................................... 6 Student Objectives .................................................... 6 Follow-Up Activities .................................................... 6 Internet Resources .................................................... 7 Answer Key .................................................... 8 Script of Video Narration .................................................... 12 Blackline Masters Index .................................................... 20 Pre-Test .................................................... 21 Video Quiz .................................................... 22 Post-Test .................................................... 23 Discussion Questions .................................................... 27 Vocabulary Terms .................................................... 28 Woman’s Portrait .................................................... 29 -

Rights and Responsibilities in Wartime AUTHOR: NICHOLAS E

HOW WWI CHANGED AMERICA Rights and Responsibilities in Wartime AUTHOR: NICHOLAS E. CODDINGTON, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY CONTEXT Although the United States is a nation with defined rights protected by a constitution, sometimes those rights are challenged by the circumstances at hand. This is especially true during wartime and times of crisis. As Americans remained divided in their support for World War I, President Woodrow Wilson’s administration and U.S. Congress pushed pro- war propaganda and enacted laws meant to deter anti-war protesting. When war protests did arise, those who challenged U.S. involvement in the war faced heavy consequences, including jail time for their actions. Many questioned the pro-war campaign and its possible infringement on Americans’ First Amendment freedoms, including the right to protest and freedom of speech. Using World War I as a backdrop and the First Amendment as the test, students will examine the Sedition Act of 1918 and come to realize that Congress passed laws that violated the Constitution and that the Supreme Court upheld those laws. Additionally, students will be challenged to consider the role President Wilson had in promoting an anti-immigrant sentiment in the United States and how that rhetoric emboldened Congress to pass laws that violated the civil rights of all Americans. The lesson will wrap up challenging students to consider the responsibilities of citizens when they believe the president and Congress promote legislation that infringes on First Amendment rights. PRIMARY SOURCES Eugene Debs -

Wyoming Liberty Group and the Goldwater Institute Scharf-Norton Center for Constitutional Litigation in Support of Appellant on Supplemental Question

No. 08-205 ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- CITIZENS UNITED, Appellant, v. FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION, Appellee. --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- On Appeal From The United States District Court For The District Of Columbia --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE THE WYOMING LIBERTY GROUP AND THE GOLDWATER INSTITUTE SCHARF-NORTON CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL LITIGATION IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANT ON SUPPLEMENTAL QUESTION --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- BENJAMIN BARR Counsel of Record GOVERNMENT WATCH, P.C. 619 Pickford Place N.E. Washington, DC 20002 (240) 863-8280 ================================================================ COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO. (800) 225-6964 OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS ......................................... i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................... ii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ........................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................................ 2 ARGUMENT ........................................................... 3 I. Historic Truths: The Powerful Few Forever Seek to Silence Dissent ................................ 5 II. This Court Cannot Design a Workable Standard to Weed Out “Impure” Speech ..... 11 III. A Return to First Principles: Favoring Unbridled Dissent ....................................... -

*1573 the Limits of National Security

Jamshidi, Maryam 8/15/2019 For Educational Use Only THE LIMITS OF NATIONAL SECURITY, 48 Am. Crim. L. Rev. 1573 48 Am. Crim. L. Rev. 1573 American Criminal Law Review Fall, 2011 Symposium: Moving Targets: Issues at the Intersection of National Security and American Criminal Law Article Laura K. Donohuea1 Copyright © 2012 by American Criminal Law Review; Laura K. Donohue *1573 THE LIMITS OF NATIONAL SECURITY I. INTRODUCTION 1574 II. DEFINING U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY 1577 III. THE FOUR EPOCHS 1587 A. Protecting the Union: 1776-1898 1589 1. International Independence and Economic Growth 1593 2. Retreat to Union 1611 3. Return to International Independence and Economic Growth 1617 a. Tension Between Expansion and Neutrality 1618 b. Increasing Number of Domestic Power-Bases 1623 B. Formative International Engagement and Domestic Power: 1898-1930 1630 1. Political, Economic, and Military Concerns 1630 a. Military Might 1637 b. Secondary Inquiry: From Rule of Law to Type of Law 1638 2. Tension Between the Epochs: Independence v. Engagement 1645 © 2019 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 1 Jamshidi, Maryam 8/15/2019 For Educational Use Only THE LIMITS OF NATIONAL SECURITY, 48 Am. Crim. L. Rev. 1573 3. Expanding National Spheres of Influence 1650 C. The Ascendance of National Security: 1930-1989 1657 1. A New Domestic Order 1658 a. Re-channeling of Law Enforcement to National Security 1661 b. The Threat of Totalitarianism 1665 c. The Purpose of the State 1666 2. Changing International Role: From Authoritarianism to Containment 1669 3. Institutional Questions and the National Security Act of 1947 1672 a. -

Civil Liberties in the Time of Influenza

76 Articles 77 Traces: Te UNC-Chapel Hill Journal of History of the Spanish Flu and remains infuential due to its exhaustive statistical analyses and Civil Liberties in the Time of Infuenza Denton Ong thorough research from numerous localities. It remains the authoritative text on the Spanish Infuenza in the United States, focusing on the efects, scale, and spread of the Te Spanish Infuenza pandemic of 1918-1919 was one disease. Te statistics provided on mortality rates, infection rates and the disease’s spread of the deadliest outbreaks in the history of mankind, killing are still some of the most expansive in the literature. John Barry’s Te Great Infuenza over 50 million people worldwide and as many as 675,000 in (2004) compares the disease to the threat of avian fu in the twenty-frst century and 1 the United States in less than two years. Overall, the dis- covers the role of wartime censorship on the epidemic. However, Barry primarily wants ease’s mortality rate was approximately 2,500% greater than to paint a rough narrative history of the disease and the important individuals involved. 2 the average mortality rate for normal infuenza. In total, By taking a broad view of the infuenza epidemic in the United States, Te Great Infuen- the fu aficted over a quarter of all Americans and dropped za loses some of its punch, as it fnds itself trying to be several diferent kinds of histories 3 the average life expectancy in the US by 12 years. Despite all at once. the US government’s best eforts to assure the public that In Flu: A Social History of Infuenza (2008), Tom Quinn covers the efects infuenza there was no reason to panic, panic set in around the coun- outbreaks have had on society throughout history, so he only focuses on the 1918-19 try. -

Constitutionalism and the Foundations of the Security State Aziz Rana Cornell Law School, [email protected]

Cornell University Law School Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository Cornell Law Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 4-2015 Constitutionalism and the Foundations of the Security State Aziz Rana Cornell Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Legal History, Theory and Process Commons, and the National Security Commons Recommended Citation Aziz Rana, "Constitutionalism and the Foundations of the Security State," 103 California Law Review (2015) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Constitutionalism and the Foundations of the Security State Aziz Rana Scholars often argue that the culture of American constitutionalism provides an important constraint on aggressive national security practices. This Article challenges the conventional account by highlighting instead how modern constitutional reverence emerged in tandem with the national security state, critically functioning to reinforce and legitimize government power rather than primarily to place limits on it. This unacknowledged security origin of today’s constitutional climate speaks to a profound ambiguity in the type of public culture ultimately promoted by the Constitution. Scholars are clearly right to note that constitutional loyalty has created political space for arguments more respectful of civil rights and civil liberties, making the very worst excesses of the past less likely. At the same time, however, public discussion about protecting the Constitution—and a distinctively American way of life—has also served as a key justification for strengthening the government’s security infrastructure over the long run. -

First World War Notes 2

First World War When war burst upon Europe in August 1914, most Americans wanted no part. Wilson immediately proclaimed American neutrality and called on the nation to be neutral "in thought and in action." Yet the United States and Britain were linked by extensive economic ties and many Americans felt close emotionally with the British. Fearing a world dominated by imperial Germany, and seething over violation of neutral rights on the seas, Wilson declared war in 1917. "Sick man of Europe," Ottoman Empire, Balkan Wars: The ancient Ottoman empire had lost its grip throughout the late 1800’s. In the Balkan Wars, Balkan States gained their independence from the Ottoman Empire, called the "sick man of Europe." From it, the newly independent nations of Romania, Bulgaria, and Serbia were created. Triple Entente: Allies: Beginning in the early 1900’s, Britain, France and Russia had signed treaties with each other. After Austria declared war on Serbia, Germany declared war on the allies (Russia and France), in turn drawing Great Britain into the war. This system of alliances had escalated what was once a localized incident. Triple Alliance: Central Powers: The Triple Alliance consisted of Germany, Austria- Hungary, as well as Italy. Germany, with its blank check provision to Austria- Hungary, had in encouraged the war declaration on Serbia. Afterwards, Germany declared war on Russia and France, Serbia’s allies by treaties. loans to the Allies: In total, the United States lent the Allies over $10 billion. Great Britain owed the United States over $4.2 billion by the end of the war. -

Reviewing Geoffrey R. Stone, Perilous Times: Free Speech in War Time

REVIEW ESSAY A Prescription for Perilous Times Review of PERILOUS TIMES:FREE SPEECH IN WARTIME FROM THE SEDITION ACT OF 1798 TO THE WAR ON TERRORISM. By Geoffrey R. Stone. W.W. Norton & Company, 2004. 730 pages. NEIL S. SIEGEL* INTRODUCTION It seldom happens that a scholar makes a lasting contribution both to legal history and to the most pressing constitutional issues of the day in the same work. It is more rare that an academic does so in a book accessible to a general audience. Perilous Times1 accomplishes that feat. For these reasons, and for another as well, the book should be regarded as a triumph. University of Chicago Law Professor Geoffrey R. Stone has written an important work of constitutional history, not only because of what he has to say, but also because of the time in which he says it. The tragedy of September 11, 2001 generated reactions by every branch of the federal government, as well as by the general public and a host of public-regarding institutions in American society. Each of those reactions has implicated the balance between liberty and security that historically has been tested in this country during times of crisis. Perilous Times lucidly constructs and conveys the nation’s accumulated lessons of experience from the Sedition Act of 1798 to recent events in the “war on terrorism,” thereby arming Americans with some of the knowledge necessary to grapple successfully with the challenges of our own time. Professor Stone, in other words, offers not just a bracing reminder of historic threats to America’s celebrated civil liberties tradition, but also a constitutional compass for current use in a world that has changed in important respects yet remains much the same. -

Woodrow Wilson's Hidden Stroke of 1919: the Impact of Patient

NEUROSURGICAL FOCUS Neurosurg Focus 39 (1):E6, 2015 Woodrow Wilson’s hidden stroke of 1919: the impact of patient-physician confidentiality on United States foreign policy Richard P. Menger, MD,1 Christopher M. Storey, MD, PhD,1 Bharat Guthikonda, MD,1 Symeon Missios, MD,1 Anil Nanda, MD, MPH,1 and John M. Cooper, PhD2 1Department of Neurosurgery, Louisiana State University of Health Sciences, Shreveport, Louisiana; and 2University of Wisconsin Department of History, Madison, Wisconsin World War I catapulted the United States from traditional isolationism to international involvement in a major European conflict. Woodrow Wilson envisaged a permanent American imprint on democracy in world affairs through participa- tion in the League of Nations. Amid these defining events, Wilson suffered a major ischemic stroke on October 2, 1919, which left him incapacitated. What was probably his fourth and most devastating stroke was diagnosed and treated by his friend and personal physician, Admiral Cary Grayson. Grayson, who had tremendous personal and professional loyalty to Wilson, kept the severity of the stroke hidden from Congress, the American people, and even the president himself. During a cabinet briefing, Grayson formally refused to sign a document of disability and was reluctant to address the subject of presidential succession. Wilson was essentially incapacitated and hemiplegic, yet he remained an active president and all messages were relayed directly through his wife, Edith. Patient-physician confidentiality superseded national security amid the backdrop of friendship and political power on the eve of a pivotal juncture in the history of American foreign policy. It was in part because of the absence of Woodrow Wilson’s vocal and unwavering support that the United States did not join the League of Nations and distanced itself from the international stage.