Criminal Libel in the Land of the First Amendment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

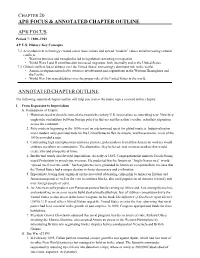

Chapter 20 Ap® Focus & Annotated Chapter Outline Ap® Focus

CHAPTER 20 AP® FOCUS & ANNOTATED CHAPTER OUTLINE AP® FOCUS Period 7: 1890–1945 AP U.S. History Key Concepts 7.2 A revolution in technology created a new mass culture and spread “modern” values amid increasing cultural conflicts. • Wartime tensions and xenophobia led to legislation restricting immigration. • World Wars I and II contributed to increased migration, both internally and to the United States. 7.3 Global conflicts led to debates over the United States’ increasingly dominant role in the world. • American expansionism led to overseas involvement and acquisitions in the Western Hemisphere and the Pacific. • World War I increased debates over the proper role of the United States in the world. ANNOTATED CHAPTER OUTLINE The following annotated chapter outline will help you review the major topics covered in this chapter. I. From Expansion to Imperialism A. Foundations of Empire 1. Historians used to describe turn-of-the-twentieth-century U.S. imperialism as something new. Now they emphasize continuities between foreign policy in this era and the nation’s earlier, relentless expansion across the continent. 2. Policymakers beginning in the 1890s went on a determined quest for global markets. Industrialization and a modern navy provided tools for the United States to flex its muscle, and the economic crisis of the 1890s provided a spur. 3. Confronting high unemployment and mass protests, policymakers feared that American workers would embrace socialism or communism. The alternative, they believed, was overseas markets that would create jobs and prosperity at home. 4. Intellectual trends also favored imperialism. As early as 1885, Congregationalist minister Josiah Strong urged Protestants to proselytize overseas. -

Espionage Act of 1917

Communication Law Review An Analysis of Congressional Arguments Limiting Free Speech Laura Long, University of Oklahoma The Alien and Sedition Acts, Espionage and Sedition Acts, and USA PATRIOT Act are all war-time acts passed by Congress which are viewed as blatant civil rights violations. This study identifies recurring arguments presented during congressional debates of these acts. Analysis of the arguments suggests that Terror Management Theory may explain why civil rights were given up in the name of security. Further, the citizen and non-citizen distinction in addition to political ramifications are discussed. The Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 are considered by many as gross violations of civil liberties and constitutional rights. John Miller, in his book, Crisis in Freedom, described the Alien and Sedition Acts as a failure from every point of view. Miller explained the Federalists’ “disregard of the basic freedoms of Americans [completed] their ruin and cost them the confidence and respect of the people.”1 John Adams described the acts as “an ineffectual attempt to extinguish the fire of defamation, but it operated like oil upon the flames.”2 Other scholars have claimed that the acts were not simply unwise policy, but they were unconstitutional measures.3 In an article titled “Order vs. Liberty,” Larry Gragg argued that they were blatantly against the First Amendment protections outlined only seven years earlier.4 Despite popular opinion that the acts were unconstitutional and violated basic civil liberties, arguments used to pass the acts have resurfaced throughout United States history. Those arguments seek to instill fear in American citizens that foreigners will ultimately be the demise to the United States unless quick and decisive action is taken. -

American Influence on Israel's Jurisprudence of Free Speech Pnina Lahav

Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly Volume 9 Article 2 Number 1 Fall 1981 1-1-1981 American Influence on Israel's Jurisprudence of Free Speech Pnina Lahav Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Pnina Lahav, American Influence on Israel's Jurisprudence of Free Speech, 9 Hastings Const. L.Q. 21 (1981). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly/vol9/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES American Influence on Israel's Jurisprudence of Free Speech By PNINA LAHAV* Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................ 23 Part 1: 1953-Enter Probable Danger ............................... 27 A. The Case of Kol-Ha'am: A Brief Summation .............. 27 B. The Recipient System on the Eve of Transplantation ....... 29 C. Justice Agranat: An Anatomy of Transplantation, Grand Style ...................................................... 34 D. Jurisprudence: Interest Balancing as the Correct Method to Define the Limitations on Speech .......................... 37 1. The Substantive Material Transplanted ................. 37 2. The Process of Transplantation -

No. 11-210 in the Supreme Court of the United States ______UNITED STATES of AMERICA, Petitioner, V

No. 11-210 In the Supreme Court of the United States ______________________________________________ UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Petitioner, v. XAVIER ALVAREZ, Respondent. ___________________________________________ ON THE WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT __________________________________________ AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF OF THE THOMAS JEFFERSON CENTER FOR THE PROTECTION OF FREE EXPRESSION IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENT BRUCE D. BROWN J. JOSHUA WHEELER* BAKER HOSTETLER LLP JESSE HOWARD BAKER IV WASHINGTON SQUARE The Thomas Jefferson 1050 Connecticut Avenue, NW Center for the Protection of Washington, DC 20036-5304 Free Expression P: 202-861-1660 400 Worrell Drive [email protected] Charlottesville, VA 22911 P: 434-295-4784 KATAYOUN A. DONNELLY [email protected] BAKER HOSTETLER LLP 303 East 17th Avenue Denver, CO 80203-1264 303-861-4038 [email protected] *Counsel of Record for Amicus Curiae TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .................................... iv STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ................................................................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .................................. 1 ARGUMENT ............................................................. 3 I. THE STOLEN VALOR ACT CREATES AN UNPROTECTED CATEGORY OF SPEECH NOT PREVIOUSLY RECOGNIZED IN THIS COURT‘S FIRST AMENDMENT DECISIONS. A. The statute does not regulate fraudulent or defamatory speech. ............. 4 B. The historical tradition of stringent restrictions on the speech of military personnel does not encompass false statements about military service made by civilians ........................................ 5 II. HISTORY REJECTS AN EXCEPTION TO THE FIRST AMENDMENT BASED ON PROTECTING THE REPUTATION OF GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS. A. Origins of seditious libel laws. ................... 8 B. The court‘s reflections on seditious libel laws. .................................................. 11 ii III. NEITHER CONGRESS NOR THE COURTS MAY SIMPLY CREATE NEW CATEGORIES OF UNPROTECTED SPEECH BASED ON A BALANCING TEST. -

The War to End All Wars. COMMEMORATIVE

FALL 2014 BEFORE THE NEW AGE and the New Frontier and the New Deal, before Roy Rogers and John Wayne and Tom Mix, before Bugs Bunny and Mickey Mouse and Felix the Cat, before the TVA and TV and radio and the Radio Flyer, before The Grapes of Wrath and Gone with the Wind and The Jazz Singer, before the CIA and the FBI and the WPA, before airlines and airmail and air conditioning, before LBJ and JFK and FDR, before the Space Shuttle and Sputnik and the Hindenburg and the Spirit of St. Louis, before the Greed Decade and the Me Decade and the Summer of Love and the Great Depression and Prohibition, before Yuppies and Hippies and Okies and Flappers, before Saigon and Inchon and Nuremberg and Pearl Harbor and Weimar, before Ho and Mao and Chiang, before MP3s and CDs and LPs, before Martin Luther King and Thurgood Marshall and Jackie Robinson, before the pill and Pampers and penicillin, before GI surgery and GI Joe and the GI Bill, before AFDC and HUD and Welfare and Medicare and Social Security, before Super Glue and titanium and Lucite, before the Sears Tower and the Twin Towers and the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building, before the In Crowd and the A Train and the Lost Generation, before the Blue Angels and Rhythm & Blues and Rhapsody in Blue, before Tupperware and the refrigerator and the automatic transmission and the aerosol can and the Band-Aid and nylon and the ballpoint pen and sliced bread, before the Iraq War and the Gulf War and the Cold War and the Vietnam War and the Korean War and the Second World War, there was the First World War, World War I, The Great War, The War to End All Wars. -

Marshall Islands Consolidated Legislation

Criminal Code [31 MIRC Ch 1] http://www.paclii.org/mh/legis/consol_act/cc94/ Home | Databases | WorldLII | Search | Feedback Marshall Islands Consolidated Legislation You are here: PacLII >> Databases >> Marshall Islands Consolidated Legislation >> Criminal Code [31 MIRC Ch 1] Database Search | Name Search | Noteup | Download | Help Criminal Code [31 MIRC Ch 1] 31 MIRC Ch 1 MARSHALL ISLANDS REVISED CODE 2004 TITLE 31. - CRIMES AND PUNISHMENTS CHAPTER 1. CRIMINAL CODE ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Section PART I - GENERAL PROVISIONS §101 . Short title. §102 . Classification of crimes. §103. Definitions, Burden of Proof; General principles of liability; Requirements of culpability. §104 . Accessories. §105 . Attempts. §106 . Insanity. §107 . Presumption as to responsibility of children. §108 . Limitation of prosecution. §109. Limitation of punishment for crimes in violation of native customs. PART II - ABUSE OF PROCESS §110 . Interference with service of process. §111 .Concealment, removal or alteration of record or process. PART III - ARSON §112 . Defined; punishment. PART IV - ASSAULT AND BATTERY §113 . Assault. §114 . Aggravated assault. §115 . Assault and battery. §116 . Assault and battery with a dangerous weapon. 1 of 37 25/08/2011 14:51 Criminal Code [31 MIRC Ch 1] http://www.paclii.org/mh/legis/consol_act/cc94/ PART V - BIGAMY §117 . Defined; punishment. PART VI - BRIBERY §118 . Defined; punishment. PART VII - BURGLARY §119. Defined; punishment. PART VIII - CONSPIRACY §120 . Defined, punishment. PART IX – COUNTERFEITING §121 . Defined; punishment. PART X - DISTURBANCES, RIOTS, AND OTHER CRIMES AGAINST THE PEACE §122 . Disturbing the peace. §123 . Riot. §124. Drunken and disorderly conduct. §125 . Affray. §126 . Security to keep the peace. PART XI - ESCAPE AND RESCUE §127. Escape. -

World War I - on the Homefront

World War I - On the Homefront Teacher’s Guide Written By: Melissa McMeen Produced and Distributed by: www.MediaRichLearning.com AMERICA IN THE 20TH CENTURY: WORLD WAR I—ON THE HOMEFRONT TEACHER’S GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Materials in Unit .................................................... 3 Introduction to the Series .................................................... 3 Introduction to the Program .................................................... 3 Standards .................................................... 4 Instructional Notes .................................................... 5 Suggested Instructional Procedures .................................................... 6 Student Objectives .................................................... 6 Follow-Up Activities .................................................... 6 Internet Resources .................................................... 7 Answer Key .................................................... 8 Script of Video Narration .................................................... 12 Blackline Masters Index .................................................... 20 Pre-Test .................................................... 21 Video Quiz .................................................... 22 Post-Test .................................................... 23 Discussion Questions .................................................... 27 Vocabulary Terms .................................................... 28 Woman’s Portrait .................................................... 29 -

Choctaw Nation Criminal Code

Choctaw Nation Criminal Code Table of Contents Part I. In General ........................................................................................................................ 38 Chapter 1. Preliminary Provisions ............................................................................................ 38 Section 1. Title of code ............................................................................................................. 38 Section 2. Criminal acts are only those prescribed ................................................................... 38 Section 3. Crime and public offense defined ............................................................................ 38 Section 4. Crimes classified ...................................................................................................... 38 Section 5. Felony defined .......................................................................................................... 39 Section 6. Misdemeanor defined ............................................................................................... 39 Section 7. Objects of criminal code .......................................................................................... 39 Section 8. Conviction must precede punishment ...................................................................... 39 Section 9. Punishment of felonies ............................................................................................. 39 Section 10. Punishment of misdemeanor ................................................................................. -

Rights and Responsibilities in Wartime AUTHOR: NICHOLAS E

HOW WWI CHANGED AMERICA Rights and Responsibilities in Wartime AUTHOR: NICHOLAS E. CODDINGTON, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY CONTEXT Although the United States is a nation with defined rights protected by a constitution, sometimes those rights are challenged by the circumstances at hand. This is especially true during wartime and times of crisis. As Americans remained divided in their support for World War I, President Woodrow Wilson’s administration and U.S. Congress pushed pro- war propaganda and enacted laws meant to deter anti-war protesting. When war protests did arise, those who challenged U.S. involvement in the war faced heavy consequences, including jail time for their actions. Many questioned the pro-war campaign and its possible infringement on Americans’ First Amendment freedoms, including the right to protest and freedom of speech. Using World War I as a backdrop and the First Amendment as the test, students will examine the Sedition Act of 1918 and come to realize that Congress passed laws that violated the Constitution and that the Supreme Court upheld those laws. Additionally, students will be challenged to consider the role President Wilson had in promoting an anti-immigrant sentiment in the United States and how that rhetoric emboldened Congress to pass laws that violated the civil rights of all Americans. The lesson will wrap up challenging students to consider the responsibilities of citizens when they believe the president and Congress promote legislation that infringes on First Amendment rights. PRIMARY SOURCES Eugene Debs -

Reforming the Crime of Libel

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE NYLS Law Review Vols. 22-63 (1976-2019) Volume 50 Issue 1 International and Comparative Perspectives on Defamation, Free Speech, and Article 7 Privacy January 2006 Reforming the Crime of Libel Clive Walker University of Leeds School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review Part of the Criminal Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Clive Walker, Reforming the Crime of Libel, 50 N.Y.L. SCH. L. REV. (2005-2006). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. \\server05\productn\N\NLR\50-1\NLR106.txt unknown Seq: 1 20-FEB-06 12:31 REFORMING THE CRIME OF LIBEL CLIVE WALKER* I. INTRODUCTION Criminal libel has a long and troubled history — longer and even more troubled than its counterpart in civil law. In its early guises, it was notable as an instrument of state repression alongside other variants of libel such as blasphemy and sedition and, in part, as a corrective to the end of press licensing. But its usage in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries became less state-oriented. Though its status as a crime inevitably brings with it an element of official sanction, criminal libel has latterly evolved as the weapon of most destruction in the arsenal of libel law. In this role, it has be- come a rarity but has survived attempts at eradication in England and Wales and even the United States. -

Wyoming Liberty Group and the Goldwater Institute Scharf-Norton Center for Constitutional Litigation in Support of Appellant on Supplemental Question

No. 08-205 ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- CITIZENS UNITED, Appellant, v. FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION, Appellee. --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- On Appeal From The United States District Court For The District Of Columbia --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE THE WYOMING LIBERTY GROUP AND THE GOLDWATER INSTITUTE SCHARF-NORTON CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL LITIGATION IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANT ON SUPPLEMENTAL QUESTION --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- BENJAMIN BARR Counsel of Record GOVERNMENT WATCH, P.C. 619 Pickford Place N.E. Washington, DC 20002 (240) 863-8280 ================================================================ COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO. (800) 225-6964 OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS ......................................... i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................... ii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ........................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................................ 2 ARGUMENT ........................................................... 3 I. Historic Truths: The Powerful Few Forever Seek to Silence Dissent ................................ 5 II. This Court Cannot Design a Workable Standard to Weed Out “Impure” Speech ..... 11 III. A Return to First Principles: Favoring Unbridled Dissent ....................................... -

*1573 the Limits of National Security

Jamshidi, Maryam 8/15/2019 For Educational Use Only THE LIMITS OF NATIONAL SECURITY, 48 Am. Crim. L. Rev. 1573 48 Am. Crim. L. Rev. 1573 American Criminal Law Review Fall, 2011 Symposium: Moving Targets: Issues at the Intersection of National Security and American Criminal Law Article Laura K. Donohuea1 Copyright © 2012 by American Criminal Law Review; Laura K. Donohue *1573 THE LIMITS OF NATIONAL SECURITY I. INTRODUCTION 1574 II. DEFINING U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY 1577 III. THE FOUR EPOCHS 1587 A. Protecting the Union: 1776-1898 1589 1. International Independence and Economic Growth 1593 2. Retreat to Union 1611 3. Return to International Independence and Economic Growth 1617 a. Tension Between Expansion and Neutrality 1618 b. Increasing Number of Domestic Power-Bases 1623 B. Formative International Engagement and Domestic Power: 1898-1930 1630 1. Political, Economic, and Military Concerns 1630 a. Military Might 1637 b. Secondary Inquiry: From Rule of Law to Type of Law 1638 2. Tension Between the Epochs: Independence v. Engagement 1645 © 2019 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 1 Jamshidi, Maryam 8/15/2019 For Educational Use Only THE LIMITS OF NATIONAL SECURITY, 48 Am. Crim. L. Rev. 1573 3. Expanding National Spheres of Influence 1650 C. The Ascendance of National Security: 1930-1989 1657 1. A New Domestic Order 1658 a. Re-channeling of Law Enforcement to National Security 1661 b. The Threat of Totalitarianism 1665 c. The Purpose of the State 1666 2. Changing International Role: From Authoritarianism to Containment 1669 3. Institutional Questions and the National Security Act of 1947 1672 a.