Wyoming Liberty Group and the Goldwater Institute Scharf-Norton Center for Constitutional Litigation in Support of Appellant on Supplemental Question

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Highly Partisan Reception Greets Palin As V.P. Pick

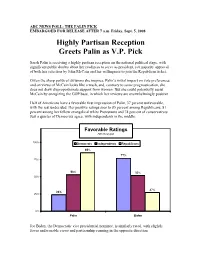

ABC NEWS POLL: THE PALIN PICK EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE AFTER 7 a.m. Friday, Sept. 5, 2008 Highly Partisan Reception Greets Palin as V.P. Pick Sarah Palin is receiving a highly partisan reception on the national political stage, with significant public doubts about her readiness to serve as president, yet majority approval of both her selection by John McCain and her willingness to join the Republican ticket. Given the sharp political divisions she inspires, Palin’s initial impact on vote preferences and on views of McCain looks like a wash, and, contrary to some prognostication, she does not draw disproportionate support from women. But she could potentially assist McCain by energizing the GOP base, in which her reviews are overwhelmingly positive. Half of Americans have a favorable first impression of Palin, 37 percent unfavorable, with the rest undecided. Her positive ratings soar to 85 percent among Republicans, 81 percent among her fellow evangelical white Protestants and 74 percent of conservatives. Just a quarter of Democrats agree, with independents in the middle. Favorable Ratings ABC News poll 100% Democrats Independents Republicans 85% 77% 75% 53% 52% 50% 27% 24% 25% 0% Palin Biden Joe Biden, the Democratic vice presidential nominee, is similarly rated, with slightly fewer unfavorable views and partisanship running in the opposite direction. Palin: Biden: Favorable Unfavorable Favorable Unfavorable All 50% 37 54% 30 Democrats 24 63 77 9 Independents 53 34 52 31 Republicans 85 7 27 60 Men 54 37 55 35 Women 47 36 54 27 IMPACT – The public by a narrow 6-point margin, 25 percent to 19 percent, says Palin’s selection makes them more likely to support McCain, less than the 12-point positive impact of Biden on the Democratic ticket (22 percent more likely to support Barack Obama, 10 percent less so). -

Picking the Vice President

Picking the Vice President Elaine C. Kamarck Brookings Institution Press Washington, D.C. Contents Introduction 4 1 The Balancing Model 6 The Vice Presidency as an “Arranged Marriage” 2 Breaking the Mold 14 From Arranged Marriages to Love Matches 3 The Partnership Model in Action 20 Al Gore Dick Cheney Joe Biden 4 Conclusion 33 Copyright 36 Introduction Throughout history, the vice president has been a pretty forlorn character, not unlike the fictional vice president Julia Louis-Dreyfus plays in the HBO seriesVEEP . In the first episode, Vice President Selina Meyer keeps asking her secretary whether the president has called. He hasn’t. She then walks into a U.S. senator’s office and asks of her old colleague, “What have I been missing here?” Without looking up from her computer, the senator responds, “Power.” Until recently, vice presidents were not very interesting nor was the relationship between presidents and their vice presidents very consequential—and for good reason. Historically, vice presidents have been understudies, have often been disliked or even despised by the president they served, and have been used by political parties, derided by journalists, and ridiculed by the public. The job of vice president has been so peripheral that VPs themselves have even made fun of the office. That’s because from the beginning of the nineteenth century until the last decade of the twentieth century, most vice presidents were chosen to “balance” the ticket. The balance in question could be geographic—a northern presidential candidate like John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts picked a southerner like Lyndon B. -

Chapter 20 Ap® Focus & Annotated Chapter Outline Ap® Focus

CHAPTER 20 AP® FOCUS & ANNOTATED CHAPTER OUTLINE AP® FOCUS Period 7: 1890–1945 AP U.S. History Key Concepts 7.2 A revolution in technology created a new mass culture and spread “modern” values amid increasing cultural conflicts. • Wartime tensions and xenophobia led to legislation restricting immigration. • World Wars I and II contributed to increased migration, both internally and to the United States. 7.3 Global conflicts led to debates over the United States’ increasingly dominant role in the world. • American expansionism led to overseas involvement and acquisitions in the Western Hemisphere and the Pacific. • World War I increased debates over the proper role of the United States in the world. ANNOTATED CHAPTER OUTLINE The following annotated chapter outline will help you review the major topics covered in this chapter. I. From Expansion to Imperialism A. Foundations of Empire 1. Historians used to describe turn-of-the-twentieth-century U.S. imperialism as something new. Now they emphasize continuities between foreign policy in this era and the nation’s earlier, relentless expansion across the continent. 2. Policymakers beginning in the 1890s went on a determined quest for global markets. Industrialization and a modern navy provided tools for the United States to flex its muscle, and the economic crisis of the 1890s provided a spur. 3. Confronting high unemployment and mass protests, policymakers feared that American workers would embrace socialism or communism. The alternative, they believed, was overseas markets that would create jobs and prosperity at home. 4. Intellectual trends also favored imperialism. As early as 1885, Congregationalist minister Josiah Strong urged Protestants to proselytize overseas. -

Suffolk University Virginia General Election Voters SUPRC Field

Suffolk University Virginia General Election Voters AREA N= 600 100% DC Area ........................................ 1 ( 1/ 98) 164 27% West ........................................... 2 51 9% Piedmont Valley ................................ 3 134 22% Richmond South ................................. 4 104 17% East ........................................... 5 147 25% START Hello, my name is __________ and I am conducting a survey for Suffolk University and I would like to get your opinions on some political questions. We are calling Virginia households statewide. Would you be willing to spend three minutes answering some brief questions? <ROTATE> or someone in that household). N= 600 100% Continue ....................................... 1 ( 1/105) 600 100% GEND RECORD GENDER N= 600 100% Male ........................................... 1 ( 1/106) 275 46% Female ......................................... 2 325 54% S2 S2. Thank You. How likely are you to vote in the Presidential Election on November 4th? N= 600 100% Very likely .................................... 1 ( 1/107) 583 97% Somewhat likely ................................ 2 17 3% Not very/Not at all likely ..................... 3 0 0% Other/Undecided/Refused ........................ 4 0 0% Q1 Q1. Which political party do you feel closest to - Democrat, Republican, or Independent? N= 600 100% Democrat ....................................... 1 ( 1/110) 269 45% Republican ..................................... 2 188 31% Independent/Unaffiliated/Other ................. 3 141 24% Not registered -

Espionage Act of 1917

Communication Law Review An Analysis of Congressional Arguments Limiting Free Speech Laura Long, University of Oklahoma The Alien and Sedition Acts, Espionage and Sedition Acts, and USA PATRIOT Act are all war-time acts passed by Congress which are viewed as blatant civil rights violations. This study identifies recurring arguments presented during congressional debates of these acts. Analysis of the arguments suggests that Terror Management Theory may explain why civil rights were given up in the name of security. Further, the citizen and non-citizen distinction in addition to political ramifications are discussed. The Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 are considered by many as gross violations of civil liberties and constitutional rights. John Miller, in his book, Crisis in Freedom, described the Alien and Sedition Acts as a failure from every point of view. Miller explained the Federalists’ “disregard of the basic freedoms of Americans [completed] their ruin and cost them the confidence and respect of the people.”1 John Adams described the acts as “an ineffectual attempt to extinguish the fire of defamation, but it operated like oil upon the flames.”2 Other scholars have claimed that the acts were not simply unwise policy, but they were unconstitutional measures.3 In an article titled “Order vs. Liberty,” Larry Gragg argued that they were blatantly against the First Amendment protections outlined only seven years earlier.4 Despite popular opinion that the acts were unconstitutional and violated basic civil liberties, arguments used to pass the acts have resurfaced throughout United States history. Those arguments seek to instill fear in American citizens that foreigners will ultimately be the demise to the United States unless quick and decisive action is taken. -

John S. Mccain III • Born in Panama on August 29, 1936 • Nicknamed

John S. McCain III • Born in Panama on August 29, 1936 • Nicknamed ”The Maverick” for not being afraid to disagree with his political party (Republican) • Naval aviator during the Vietnam War • Prisoner of war in Vietnam from 1967-1973 • Arizona senator since 1986 • Republican nominee for president of the United States in 2008 McCain in the Navy McCain’s father and grandfather were both admirals in the Navy. He followed in their footsteps and graduated from the Naval Academy in 1958. He is pictured here with his parents and his younger brother, Joe. His son, Jimmy, also became an officer in the Navy McCain in training (1965) As the U.S. began to increase the number of troops in Vietnam in 1965, McCain was training to become a fighter pilot. On October 26, 1967, his A-4 Skyhawk was shot down by a missile as he was flying over Hanoi. He was badly injured when he was pulled from Truc Bach Lake by North Vietnamese. Shot Down McCain’s bomber was hit by a surface-to-air missile on Oct. 26, 1967, destroying the aircraft’s right wing. According to McCain, the plane entered an “inverted, almost straight-down spin,” and he ejected. But the sheer force of the ejection broke his right leg and both arms, knocking him unconscious, the report said. McCain came to as he landed in a lake, but burdened by heavy equipment, he sank straight to the bottom. Able to kick to the surface momentarily for air, he somehow managed to activate his life preserver with his teeth. -

Getting to Know the Candidates

C M Y K C12 DAILY 01-29-08 MD RE C12 CMYK C12 Tuesday, January 29, 2008 R The Washington Post Last week’s survey Bee 10.4% asked: What is your Butterfly 35.1% favorite insect? Cockroach 8.4% More than 450 SAYS readers Ladybug 21.8% SURVEY responded: I don’t like bugs! 24.3% WEATHER has traveled around to be studied TODAY’S NEWS by paleontologists, the U.S. space SPEAK OUT agency and the National Geo- Hadrosaur’s Roaming graphic Society. THIS WEEK’S TOPIC Unlike most collections of Days Are Almost Over bones found in museums, this K Dakota the duckbilled dinosaur hadrosaur was found with fossil- Super Bowl Pick is going home to North Dakota. ized skin, ligaments, tendons and BY DIANE BONDAREFF — RUBIN MUSEUM OF ART VIA AP The New York Giants and the The 65-million-year-old fossil- possibly some internal organs, re- Wim Hof is head and shoulders above TODAY: Cloudy; New England Patriots meet other ice-bath record seekers. ized hadrosaur, found in North searchers said. rain likely. Sunday in Super Bowl XLII Dakota’s Badlands in 1999, will It was found by a high school (42). The Patriots have 18 wins be ready for display at the State student who spotted its bony tail Cold? Think Again HIGH LOW and no losses this season and Historical Society in Bismarck in while hiking on his uncle’s are trying to notch the longest early June. Since the discovery, it ranch. K Most people try to stay out of 50 38 perfect season in pro football the cold during winter. -

The War to End All Wars. COMMEMORATIVE

FALL 2014 BEFORE THE NEW AGE and the New Frontier and the New Deal, before Roy Rogers and John Wayne and Tom Mix, before Bugs Bunny and Mickey Mouse and Felix the Cat, before the TVA and TV and radio and the Radio Flyer, before The Grapes of Wrath and Gone with the Wind and The Jazz Singer, before the CIA and the FBI and the WPA, before airlines and airmail and air conditioning, before LBJ and JFK and FDR, before the Space Shuttle and Sputnik and the Hindenburg and the Spirit of St. Louis, before the Greed Decade and the Me Decade and the Summer of Love and the Great Depression and Prohibition, before Yuppies and Hippies and Okies and Flappers, before Saigon and Inchon and Nuremberg and Pearl Harbor and Weimar, before Ho and Mao and Chiang, before MP3s and CDs and LPs, before Martin Luther King and Thurgood Marshall and Jackie Robinson, before the pill and Pampers and penicillin, before GI surgery and GI Joe and the GI Bill, before AFDC and HUD and Welfare and Medicare and Social Security, before Super Glue and titanium and Lucite, before the Sears Tower and the Twin Towers and the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building, before the In Crowd and the A Train and the Lost Generation, before the Blue Angels and Rhythm & Blues and Rhapsody in Blue, before Tupperware and the refrigerator and the automatic transmission and the aerosol can and the Band-Aid and nylon and the ballpoint pen and sliced bread, before the Iraq War and the Gulf War and the Cold War and the Vietnam War and the Korean War and the Second World War, there was the First World War, World War I, The Great War, The War to End All Wars. -

For Obama, Being Right Is No Longer Enough

Unexpected and Expected Surprises in the Campaign Lincoln Mitchell, Harriman Institute, Columbia University Posted: 07/12/2012 10:09 pm The general election is now less than four months away. The election itself has taken on the predictable rhythm of many presidential elections. The primaries were less contested than usual as the Democratic incumbent had no challengers, not even a protest candidate of some kind; and the Republican challenger did not have any serious opposition throughout much of the race. Not surprisingly, the main issue in the race remains the economy as President Barack Obama is seeking to make the argument that while the economy still has its problems, due to his policies, it is moving in the right direction. Republican challenger Mitt Romney's campaign is arguing that the economy is still in terrible shape and that only the magic of more tax cuts can turn it around. None of this is unusual and, if nothing else happens, this will likely lead to a narrow, but unambiguous victory for President Obama. Something, however, almost always happens. With four months to go, there are numerous ways the race can be changed. In July of 2008, for example, the financial meltdown had still not occurred. Similarly events such as economic crises, natural disasters, terrorist attacks or other dramatic occurrences could occur at any time and change the nature of the campaign. These types of things are unlikely to occur and almost impossible to foresee in advance. Moreover, it is difficult to know in advance which candidate they will help or hurt. -

World War I - on the Homefront

World War I - On the Homefront Teacher’s Guide Written By: Melissa McMeen Produced and Distributed by: www.MediaRichLearning.com AMERICA IN THE 20TH CENTURY: WORLD WAR I—ON THE HOMEFRONT TEACHER’S GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Materials in Unit .................................................... 3 Introduction to the Series .................................................... 3 Introduction to the Program .................................................... 3 Standards .................................................... 4 Instructional Notes .................................................... 5 Suggested Instructional Procedures .................................................... 6 Student Objectives .................................................... 6 Follow-Up Activities .................................................... 6 Internet Resources .................................................... 7 Answer Key .................................................... 8 Script of Video Narration .................................................... 12 Blackline Masters Index .................................................... 20 Pre-Test .................................................... 21 Video Quiz .................................................... 22 Post-Test .................................................... 23 Discussion Questions .................................................... 27 Vocabulary Terms .................................................... 28 Woman’s Portrait .................................................... 29 -

Senator John Mccain Vietnam Veterans Memorial Plaza Brochure

I fell in love with my country when I was a prisoner in someone else’s. I loved it not just for the many comforts of life here. I loved it for its decency; for its faith in the wisdom, justice and goodness of its people. I loved it because it was not just a place, but an idea, a cause worth fighting for. I was never the same again. I wasn’t my own man anymore. I was my country’s. Senator John McCain 1936 - 2018 SENATOR JOHN MCCAIN VIETNAM VETERANS MEMORIAL PLAZA In recognition and respect of all Vietnam Veterans, the City of Peoria is proud to expand and enhance the Vietnam Memorial Plaza. DONOR CAMPAIGN To ensure this memorial forever serves as a place of reflection and learning, the City of Peoria is enlarging the plaza and adding new elements, which will allow even more visitors to honor, reflect, and learn about our military history. We are requesting your support to make these improvements a reality; and for the first time ever, your commitment will be permanently exhibited at the plaza and visible to the more than 500,000 people who visit the award-winning Rio Vista Community Park each year. Sponsorship opportunities are noted on the back page. Existing memorial PLANNED ENHANCEMENTS AND SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES SPONSOR NAME HERE Pedestal Permanent Sponsorship Memorial Benches Opportunities Permanent Sponsorship Opportunity SENATOR JOHN MCCAIN VIETNAM VETERANS MEMORIAL PLAZA SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES Tier I Sponsors who donate $15,000 Tier II Sponsors who donate or more will receive: $10,000 – $14,999 will receive: • Recognition -

Rights and Responsibilities in Wartime AUTHOR: NICHOLAS E

HOW WWI CHANGED AMERICA Rights and Responsibilities in Wartime AUTHOR: NICHOLAS E. CODDINGTON, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY CONTEXT Although the United States is a nation with defined rights protected by a constitution, sometimes those rights are challenged by the circumstances at hand. This is especially true during wartime and times of crisis. As Americans remained divided in their support for World War I, President Woodrow Wilson’s administration and U.S. Congress pushed pro- war propaganda and enacted laws meant to deter anti-war protesting. When war protests did arise, those who challenged U.S. involvement in the war faced heavy consequences, including jail time for their actions. Many questioned the pro-war campaign and its possible infringement on Americans’ First Amendment freedoms, including the right to protest and freedom of speech. Using World War I as a backdrop and the First Amendment as the test, students will examine the Sedition Act of 1918 and come to realize that Congress passed laws that violated the Constitution and that the Supreme Court upheld those laws. Additionally, students will be challenged to consider the role President Wilson had in promoting an anti-immigrant sentiment in the United States and how that rhetoric emboldened Congress to pass laws that violated the civil rights of all Americans. The lesson will wrap up challenging students to consider the responsibilities of citizens when they believe the president and Congress promote legislation that infringes on First Amendment rights. PRIMARY SOURCES Eugene Debs