The Lorne W. Craner Memorial Lecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 7, 2005 the Honorable Jim Kolbe United States House of Representatives 237 Cannon House Office Building Washington, DC

American Lands Alliance ♦ Access Fund ♦ Arizona Mountaineering Club ♦ Arizona Native Plant Society ♦ Arizona Wildlife Federation ♦ Center for Biological Diversity ♦ Chiricahua-Dragoon Conservation Alliance ♦ Citizens for the Preservation of Powers Gulch and Pinto Creek ♦ Citizens for Victor! ♦ EARTHWORKS ♦ Endangered Species Coalition ♦Friends of Queen Creek ♦ Gila Resources Information Project ♦ Grand Canyon Chapter of the Sierra Club ♦ Great Basin Mine Watch♦ The Lands Council ♦ Maricopa Audubon Society ♦ Mining Impact Coalition of Wisconsin ♦ Mount Graham Coalition ♦ National Wildlife Federation ♦ Rock Creek Alliance ♦Water More Precious Than Gold ♦ Western Land Exchange Project ♦ Yuma Audubon Society April 7, 2005 The Honorable Jim Kolbe United States House of Representatives 237 Cannon House Office Building Washington, DC 20515 Dear Representative Kolbe, On behalf of the undersigned organizations and the thousands of members we represent in Arizona and nationwide, we urge you not to introduce the Southeastern Arizona Land Exchange and Conservation Act of 2005 (the “land exchange bill”) that would, in part, revoke a mining prohibition on 760 acres of public lands in the Tonto National Forest in the area of the Oak Flat Campground 60 miles east of Phoenix. Resolution Copper Company (RCC), a foreign-owned mining company, is planning a massive block-cave mine and seeks to acquire Oak Flat Campground and the surrounding public lands for its use through this land exchange bill. If they succeed, the campground and an additional 2,300 acres of the Tonto National Forest will become private property and forever off limits to recreationists and other users. Privatization of this land would end public access to some of the most spectacular outdoor recreation and wildlife viewing areas in Arizona and cause massive surface subsidence leaving a permanent scar on the landscape and eliminating the possibility of a diversified economy for the region. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E1858 HON

E1858 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks October 12, 2001 Whereas, President George W. Bush and CONGRATULATIONS TO BILL PUT- Bill Putnam is currently the Sole Trustee of the United States Congress, acting in bipar- NAM ON BEING INDUCTED INTO the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona tisan agreement, have made available all of THE BROADCASTERS HALL OF where he resides with his wife, Kitty Broman, the resources of the federal government to FAME who is also well known in broadcasting circles. hunt down those responsible for these vi- Mr. Speaker, it is my privilege to honor Bill cious war crimes; and HON. RICHARD E. NEAL Putnam on being recognized and honored by Whereas, After these events President OF MASSACHUSETTS the Broadcasters Hall of Fame for a long and Bush declared, ‘‘The resolve of this great na- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES distinguished career that has benefitted the tion is being tested’’; and Thursday, October 11, 2001 lives of so many in the Western Massachu- setts area. Congratulations on the good work. Whereas, President Bush said in punishing Mr. NEAL of Massachusetts. Mr. Speaker, I f those responsible that ‘‘We will make no dis- would like to take a few moments today to pay tinction between the terrorists who com- tribute to Bill Putnam, a friend and constituent IN MEMORY OF MONSIGNOR mitted these acts and those who harbor of mine, and a pioneer in the broadcasting CASIMIR CIOLEK them’’; and arena. Whereas, President Bush also stated that On November 12, 2001, in New York City, in punishing the guilty we must guard Bill Putnam will be inducted into the Broad- HON. -

New Report ID

Number 21 April 2004 BAKER INSTITUTE REPORT NOTES FROM THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY OF RICE UNIVERSITY BAKER INSTITUTE CELEBRATES ITS 10TH ANNIVERSARY Vice President Dick Cheney was man you only encounter a few the keynote speaker at the Baker times in life—what I call a ‘hun- See our special Institute’s 10th anniversary gala, dred-percenter’—a person of which drew nearly 800 guests to ability, judgment, and absolute gala feature with color a black-tie dinner October 17, integrity,” Cheney said in refer- 2003, that raised more than ence to Baker. photos on page 20. $3.2 million for the institute’s “This is a man who was chief programs. Cynthia Allshouse and of staff on day one of the Reagan Rice trustee J. D. Bucky Allshouse years and chief of staff 12 years ing a period of truly momentous co-chaired the anniversary cel- later on the last day of former change,” Cheney added, citing ebration. President Bush’s administra- the fall of the Soviet Union, the Cheney paid tribute to the tion,” Cheney said. “In between, Persian Gulf War, and a crisis in institute’s honorary chair, James he led the treasury department, Panama during Baker’s years at A. Baker, III, and then discussed oversaw two landslide victories in the Department of State. the war on terrorism. presidential politics, and served “There is a certain kind of as the 61st secretary of state dur- continued on page 24 NIGERIAN PRESIDENT REFLECTS ON CHALLENGES FACING HIS NATION President Olusegun Obasanjo of the Republic of Nigeria observed that Africa, as a whole, has been “unstable for too long” during a November 5, 2003, presentation at the Baker Institute. -

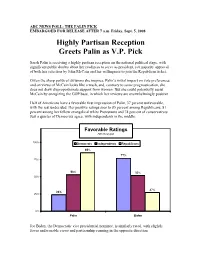

Highly Partisan Reception Greets Palin As V.P. Pick

ABC NEWS POLL: THE PALIN PICK EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE AFTER 7 a.m. Friday, Sept. 5, 2008 Highly Partisan Reception Greets Palin as V.P. Pick Sarah Palin is receiving a highly partisan reception on the national political stage, with significant public doubts about her readiness to serve as president, yet majority approval of both her selection by John McCain and her willingness to join the Republican ticket. Given the sharp political divisions she inspires, Palin’s initial impact on vote preferences and on views of McCain looks like a wash, and, contrary to some prognostication, she does not draw disproportionate support from women. But she could potentially assist McCain by energizing the GOP base, in which her reviews are overwhelmingly positive. Half of Americans have a favorable first impression of Palin, 37 percent unfavorable, with the rest undecided. Her positive ratings soar to 85 percent among Republicans, 81 percent among her fellow evangelical white Protestants and 74 percent of conservatives. Just a quarter of Democrats agree, with independents in the middle. Favorable Ratings ABC News poll 100% Democrats Independents Republicans 85% 77% 75% 53% 52% 50% 27% 24% 25% 0% Palin Biden Joe Biden, the Democratic vice presidential nominee, is similarly rated, with slightly fewer unfavorable views and partisanship running in the opposite direction. Palin: Biden: Favorable Unfavorable Favorable Unfavorable All 50% 37 54% 30 Democrats 24 63 77 9 Independents 53 34 52 31 Republicans 85 7 27 60 Men 54 37 55 35 Women 47 36 54 27 IMPACT – The public by a narrow 6-point margin, 25 percent to 19 percent, says Palin’s selection makes them more likely to support McCain, less than the 12-point positive impact of Biden on the Democratic ticket (22 percent more likely to support Barack Obama, 10 percent less so). -

Presidents Worksheet 43 Secretaries of State (#1-24)

PRESIDENTS WORKSHEET 43 NAME SOLUTION KEY SECRETARIES OF STATE (#1-24) Write the number of each president who matches each Secretary of State on the left. Some entries in each column will match more than one in the other column. Each president will be matched at least once. 9,10,13 Daniel Webster 1 George Washington 2 John Adams 14 William Marcy 3 Thomas Jefferson 18 Hamilton Fish 4 James Madison 5 James Monroe 5 John Quincy Adams 6 John Quincy Adams 12,13 John Clayton 7 Andrew Jackson 8 Martin Van Buren 7 Martin Van Buren 9 William Henry Harrison 21 Frederick Frelinghuysen 10 John Tyler 11 James Polk 6 Henry Clay (pictured) 12 Zachary Taylor 15 Lewis Cass 13 Millard Fillmore 14 Franklin Pierce 1 John Jay 15 James Buchanan 19 William Evarts 16 Abraham Lincoln 17 Andrew Johnson 7, 8 John Forsyth 18 Ulysses S. Grant 11 James Buchanan 19 Rutherford B. Hayes 20 James Garfield 3 James Madison 21 Chester Arthur 22/24 Grover Cleveland 20,21,23James Blaine 23 Benjamin Harrison 10 John Calhoun 18 Elihu Washburne 1 Thomas Jefferson 22/24 Thomas Bayard 4 James Monroe 23 John Foster 2 John Marshall 16,17 William Seward PRESIDENTS WORKSHEET 44 NAME SOLUTION KEY SECRETARIES OF STATE (#25-43) Write the number of each president who matches each Secretary of State on the left. Some entries in each column will match more than one in the other column. Each president will be matched at least once. 32 Cordell Hull 25 William McKinley 28 William Jennings Bryan 26 Theodore Roosevelt 40 Alexander Haig 27 William Howard Taft 30 Frank Kellogg 28 Woodrow Wilson 29 Warren Harding 34 John Foster Dulles 30 Calvin Coolidge 42 Madeleine Albright 31 Herbert Hoover 25 John Sherman 32 Franklin D. -

Picking the Vice President

Picking the Vice President Elaine C. Kamarck Brookings Institution Press Washington, D.C. Contents Introduction 4 1 The Balancing Model 6 The Vice Presidency as an “Arranged Marriage” 2 Breaking the Mold 14 From Arranged Marriages to Love Matches 3 The Partnership Model in Action 20 Al Gore Dick Cheney Joe Biden 4 Conclusion 33 Copyright 36 Introduction Throughout history, the vice president has been a pretty forlorn character, not unlike the fictional vice president Julia Louis-Dreyfus plays in the HBO seriesVEEP . In the first episode, Vice President Selina Meyer keeps asking her secretary whether the president has called. He hasn’t. She then walks into a U.S. senator’s office and asks of her old colleague, “What have I been missing here?” Without looking up from her computer, the senator responds, “Power.” Until recently, vice presidents were not very interesting nor was the relationship between presidents and their vice presidents very consequential—and for good reason. Historically, vice presidents have been understudies, have often been disliked or even despised by the president they served, and have been used by political parties, derided by journalists, and ridiculed by the public. The job of vice president has been so peripheral that VPs themselves have even made fun of the office. That’s because from the beginning of the nineteenth century until the last decade of the twentieth century, most vice presidents were chosen to “balance” the ticket. The balance in question could be geographic—a northern presidential candidate like John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts picked a southerner like Lyndon B. -

Suffolk University Virginia General Election Voters SUPRC Field

Suffolk University Virginia General Election Voters AREA N= 600 100% DC Area ........................................ 1 ( 1/ 98) 164 27% West ........................................... 2 51 9% Piedmont Valley ................................ 3 134 22% Richmond South ................................. 4 104 17% East ........................................... 5 147 25% START Hello, my name is __________ and I am conducting a survey for Suffolk University and I would like to get your opinions on some political questions. We are calling Virginia households statewide. Would you be willing to spend three minutes answering some brief questions? <ROTATE> or someone in that household). N= 600 100% Continue ....................................... 1 ( 1/105) 600 100% GEND RECORD GENDER N= 600 100% Male ........................................... 1 ( 1/106) 275 46% Female ......................................... 2 325 54% S2 S2. Thank You. How likely are you to vote in the Presidential Election on November 4th? N= 600 100% Very likely .................................... 1 ( 1/107) 583 97% Somewhat likely ................................ 2 17 3% Not very/Not at all likely ..................... 3 0 0% Other/Undecided/Refused ........................ 4 0 0% Q1 Q1. Which political party do you feel closest to - Democrat, Republican, or Independent? N= 600 100% Democrat ....................................... 1 ( 1/110) 269 45% Republican ..................................... 2 188 31% Independent/Unaffiliated/Other ................. 3 141 24% Not registered -

Setting Course: a Congressional Management Guide

SETTING COURSE SETTING “The best thing a new Member and his or her staff can do is to sit down and read Setting Course cover to cover. It’s a book that has stood the test of time.” —House Chief of Staff SETTING “Setting Course is written as if you were having a conversation with someone who has been on Capitol Hill for 50 years and knows how things work.” —Senate Office Manager COURSE SETTING COURSE, now in its 17th edition for the 117th Congress, is a comprehensive guide to managing a congressional office. Part I is for Members-elect and freshman offices, focusing on the tasks that are most critical to a successful transition to Congress and setting up a new office. Part II focuses on defining the Member’s role — in the office and in Congress. Part III provides guidance to both freshman and veteran Members and staff on managing office operations. Setting Course is the signature publication of the Congressional Management Foundation MANAGEMENT GUIDE CONGRESSIONAL A and has been funded by grants from: Deborah Szekely A CONGRESSIONAL MANAGEMENT GUIDE THE CONGRESSIONAL MANAGEMENT FOUNDATION (CMF) is a 501(c)(3) nonpartisan nonprofit whose mission is to build EDITION FOR THE trust and effectiveness in Congress. We do this by enhancing the 117th performance of the institution, legislators and their staffs through CONGRESS research-based education and training, and by strengthening the CONGRESS bridge between Congress and the People it serves. Since 1977 CMF 117th has worked internally with Member, committee, leadership, and institutional offices in the House and Senate to identify and disseminate best practices for management, workplace environment, SPONSORED BY communications, and constituent services. -

Westland Resources Welcomes Senior Project Managers Black

THE COMPANY LINE WestLand Resources Welcomes be the first application of ultraviolet light government, the Gila River Community, the Senior Project Managers for potable water disinfection in state of Arizona, the Central Arizona Water Southern California. Conservation District and numerous cities, WestLand Resources, Inc. of Tucson, towns and irrigation districts. The plant expansion and addition of UV Arizona recently welcomed Michael J. disinfection will increase treatment On Feb. 24, Sens. Jon Kyl and John McCain Cross and Christopher E. Rife as senior capacity of the Roemer Water Filtration and Reps. J.D. Hayworth, Raul Grijalva, project managers with the Environmental Facility (WFF) from 9.6 to 14.4 million Trent Franks and Jim Kolbe introduced the Services Group. gallons per day, enhance the district’s Arizona Water Settlements Act in Congress. Cross specializes in biological resource ability to effectively treat a full range of This legislation would settle the landmark assessments, environmental impact blends from two surface sources of raw case involving Arizona water rights as well as assessments, riparian mitigation planning, water, and yield treated water in the repayment obligation owed to the federal habitat conservation planning, Endangered compliance with all current and government by Arizona for construction of Species Act compliance, threatened and foreseeable future drinking water the Central Arizona Project (CAP). endangered species surveys and hydro- standards. The pretreatment facilities will If the legislation is approved by Congress, electric licensing. He has more than 15 include coagulation, flocculation and signed by President Bush, and approved by years of experience in environmental sedimentation along with associated the Maricopa County Superior Court consulting and biological research, with chemical storage and feed facilities. -

World Bank Document

I~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Policy,Planning, and Research WORKING PAPERS Debtand International Finance InternationalEconomics Department The WorldBank August1989 Public Disclosure Authorized WPS 250 Public Disclosure Authorized The Baker Plan Progress,Shortcomings, and Future Public Disclosure Authorized William R. Cline The basic strategy spelled out in the Baker Plan (1985-88) remains valid, but stronger policy efforts are needed, banks should provide multiyear new money packages, exit bonds should be guaranteed to allow voluntary debt reduction by banks, and net capital flows to the highly indebted countries should be raised $15 billion a year. Successful emergence from the debt crisis, however, will depend primarily on sound eco- nomic policies in the debtor countries themselves. Public Disclosure Authorized The Policy, Planning. and Research Complex distributes PPR Working Papers to disseminate the findings of work in progress and to encourage the exchange of ideas among Bank staff and all others interested in development issues. T'hese papers carry the names of the authors, reflect only their views, and should be used and cited accordingly. The findings, interpiciations. and conclusions are the authors' own. They should not be attnbuted to the World Bank, its Board of Directors, its management, or any of its mernber countries. |Policy, Planning,and Roenorch | The. Baker Plan essentially made existing multilateral development banks raised net flows strategy cn the debt problem more concrete. by only one-tenth of the targeted $3 billion Like existing policy, it iejected a bankruptcy annually. If the IMF and bilateral export credit approach to the problem, judging that coerceo agencies are included, net capital flows from forgiveness would "admit defeat" and cut official sources to the highly indebted countries borrowers off from capital markets for many (HICs) actually fell, from $9 annually in 1983- years to come. -

JAMES A. BAKER, III the Case for Pragmatic Idealism Is Based on an Optimis- Tic View of Man, Tempered by Our Knowledge of Human Imperfection

Extract from Raising the Bar: The Crucial Role of the Lawyer in Society, by Talmage Boston. © State Bar of Texas 2012. Available to order at texasbarbooks.net. TWO MOST IMPORTANT LAWYERS OF THE LAST FIFTY YEARS 67 concluded his Watergate memoirs, The Right and the Power, with these words that summarize his ultimate triumph in “raising the bar”: From Watergate we learned what generations before us have known: our Constitution works. And during the Watergate years it was interpreted again so as to reaffirm that no one—absolutely no one—is above the law.29 JAMES A. BAKER, III The case for pragmatic idealism is based on an optimis- tic view of man, tempered by our knowledge of human imperfection. It promises no easy answers or quick fixes. But I am convinced that it offers our surest guide and best hope for navigating our great country safely through this precarious period of opportunity and risk in world affairs.30 In their historic careers, Leon Jaworski and James A. Baker, III, ended up in the same place—the highest level of achievement in their respective fields as lawyers—though they didn’t start from the same place. Leonidas Jaworski entered the world in 1905 as the son of Joseph Jaworski, a German-speaking Polish immigrant, who went through Ellis Island two years before Leon’s birth and made a modest living as an evangelical pastor leading small churches in Central Texas towns. James A. Baker, III, entered the world in 1930 as the son, grand- son, and great-grandson of distinguished lawyers all named James A. -

Transcript by Rev.Com Page 1 of 13 Former U.S. Secretary of State James A. Baker, III, Whose 30-Year Legacy of Public Service In

Former U.S. Secretary of State James A. Baker, III, whose 30-year legacy of public service includes senior positions under three U.S. presidents, was interviewed at the 2020 Starr Federalist Lecture at Baylor Law on Monday, October 13 at noon CDT. Secretary Baker was interviewed by accomplished author and distinguished trial lawyer Talmage Boston, as they discussed Secretary Baker’s remarkable career, the leadership lessons learned from his years of experience in public service, and the skills and capabilities of lawyers that contribute to success as effective leaders and problem-solvers. Baker and Boston also discussed Baker’s newly released biography, The Man Who Ran Washington: The Life and Times of James A. Baker III, by Peter Baker and Susan Glasser. The Wall Street Journal calls The Man Who Ran Washington “an illuminating biographical portrait of Mr. Baker, one that describes the arc of his career and, along the way, tells us something about how executive power is wielded in the nation’s capital.” In Talmage Boston’s review of The Man Who Ran Washington, published in the Washington Independent Review of Books, Boston states, “[This] book provides a complete, persuasive explanation of how this 45-year-old prominent but politically inexperienced Houston transactional lawyer arrived in the nation’s capital as undersecretary of commerce in July 1975, and within six months, began his meteoric rise to the peak of the DC power pyramid…” The New York Times calls it “enthralling,” and states that, “The former Secretary of State’s experiences as a public servant offer timeless lessons in how to use personal relationships, broad-based coalitions and tireless negotiating to advance United States interests.” The Federalist Papers are a collection of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay between 1787 and 1788.