Specific Dynamic Action, Growth and Development in Larval Atlantic Cod, Gadus Morhua Jessica A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Speed and Metabolic Cost of Digesting a Blood Meal Depends on Temperature in a Major Disease Vector Marshall D

© 2016. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2016) 219, 1893-1902 doi:10.1242/jeb.138669 RESEARCH ARTICLE The speed and metabolic cost of digesting a blood meal depends on temperature in a major disease vector Marshall D. McCue1,‡, Leigh Boardman2,*, Susana Clusella-Trullas3, Elsje Kleynhans2 and John S. Terblanche2 ABSTRACT and is believed to occur in all animals (reviewed in Jobling, 1983; The energetics of processing a meal is crucial for understanding McCue, 2006; Wang et al., 2006; Secor, 2009). Surprisingly, – energy budgets of animals in the wild. Given that digestion and its information on SDA among one of the largest taxonomic groups – associated costs may be dependent on environmental conditions, it is insects comes from very few studies (Table 1). Furthermore, the necessary to obtain a better understanding of these costs under SDA of insects remains poorly characterized in terms of the diverse conditions and identify resulting behavioural or physiological standard metrics used to characterize this phenomenon in other trade-offs. This study examines the speed and metabolic costs – in animals (e.g. magnitude, peak time, duration and coefficient). Given ’ cumulative, absolute and relative energetic terms – of processing a insects multiple roles as disease vectors, pests of agriculture, and as bloodmeal for a major zoonotic disease vector, the tsetse fly Glossina model taxa for evolutionary, climate and conservation-related brevipalpis, across a range of ecologically relevant temperatures (25, research, this constitutes a significant limitation for integrating 30 and 35°C). Respirometry showed that flies used less energy mechanistic understanding into population dynamics modelling, digesting meals faster at higher temperatures but that their starvation including population persistence and vulnerability to environmental tolerance was reduced, supporting the prediction that warmer change. -

Nutrition and Metabolism

NUTRITION AND METABOLISM Metabolism - the sum of the chemical changes that occur in the cell and involve the breakdown (catabolism) and synthesis (anabolism) of stored energy sources. Basal Metabolic Rate is dened as the rate of energy production by the body measured under a dened set of conditions which is usually at rest (physical and mental), room temperature, 12 hours after a meal. The result is produced as a percentage of a standard value which is derived from studies of normal healthy people. Measurement of the metabolic rate takes place using a method called calorimetry. This may be done directly by measuring the amount of heat produced by the body in an Atwater chamber, the metabolic rate is the amount of heat produced per hour. More commonly the metabolic rate is determined indirectly by putting people on a closed circuit breathing system, with CO2 removed by a soda lime scrubber and the rate of oxygen consumption measured by change in volume. Oxygen consumption is proportional to the metabolic rate because most of the energy in the body is derived from oxidative phosphorylation, which uses a set amount of oxygen to produce a set amount of energy. For every litre of oxygen consumed the body produces (uses) 4.82 kcals of energy. If the oxygen consumption is 250ml/min (15L/hr) then the metabolic rate is 72.3 kcals/hr. This is often further rened by dividing the gure by the body surface area which for a 70kg male is 1.73m2. This gives an average BMR of approximately 40 kcal/m2/hr. -

Approved: Tre Specific Dynamic Action of Fat and P

TRE SPECIFIC DYNAMIC ACTION OF CARBOHYD.RATF, " FAT AND P.ROJ!EIN IN FIVE WOMEN by P.:l.tricia Jo ~~IG.n.'lley Thesis submitted to the Graduate faculty of the Virginie. Fblytechnic Institute in candidacy for the degree of MAmR OF SCIENCE in RUMAN NllfRITION AND FOODS APPROVED: "Ms.cy W. Korsliind • June, 1966 Blacksburg, Virginia -2- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ·LIST OF TABLES • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 3 LIST OF FIGURES . " . 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT • • . .. 5 Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION . 6 II. REVIEW OF LITERATURE • . 9 Summary of Specific Dynamic Action Theories . 9 Specific Dynamic Action of Carbohydrate . • 10 Specific Dynamic Action of Fat , • . 14 Specific Dynamic Action of Protein . .. 15 III. METHODS AND PROCEDURES . 18 Subjects . 18 Adminilt~ation of Food and Measurements . .. 19 Collection and Analysis of Expired Air • . 20 Calculations . • • . • • • . .- . .. 20 IV. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION • • • • • • . .. 21 Changes in Respiratory Quotient Following the Ingestion of Carbohydrate, Fat and Protein •• . 21 V;irr-;iations in He11t Production After Ingestion of Carbohydrate, Fat and Protein • • • 28 V. SUMMARY •••••• . 37 BIBLIOGRAPHY • . 38 VITA •• . ... 44 APPENDIX . 45 TABLE NUMBlll PAGE 1. Time required, aft•l' the inge•tion of carbohydrate by f tve women, to reach highest re•piratory quotient and highest heat production. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 31 2. Maximum increaee in heat production in. four women after ingestion of fat and time required for _.ximum increase to occur •••••••••••••••••• • • 31 3. Ma;xt... tacreaee in heat production in five women after ingeatioa of protein and time required for maximwll increaee to occur. • • • • • • • • • • • •. • • • • • • • 35 -4- LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE NUMBER PAGE 1~ Changes in reepiratory quotient in five women 22 after ingestion of sucrose. -

Specific Dynamic Action

Specific Dynamic Action ➢ The phenomenon of the extra heat production by the body, over and above the calculated caloric value, when a given food is metabolized by the body, is known as specific dynamic action (SDA). ➢ It is also known as calorigenic action or thermogenic action or thermic action (effect) of food. SDA for different foods ➢ For a food containing 25 g of protein, the heat production from the caloric value is 100 Cal (25 x 4 Cal). ➢ When 25 g protein is utilized by the body, 130 Cal of heat is liberated. ➢ The extra 30 Cal is the SDA of protein. ➢ SDA for protein, fat and carbohydrate 32%, 13% & 5%, ➢ Proteins possess the highest SDA while carbohydrates have the lowest. SDA for mixed diet ➢The presence of fats and carbohydrates reduces the SDA of proteins. ➢ Fats are most efficient in reducing SDA of foodstuffs. ➢ For a regularly consumed mixed diet, the SDA is around 10%. Significance of SDA ➢ For the utilization of foods by the body, certain amount of energy is consumed from the body stores. ➢ Expenditure by the body for the utilization of foodstuffs. ➢ It is the highest for proteins (30%) and lowest for carbohydrates (5%) & for mixed diet 10%. ➢ Additional 10% calories should be added to the total energy needs (of the body) towards SDA. ➢ The higher SDA for protein indicates that it is not a good source of energy. Mechanism of SDA ➢ SDA of foods is due to the energy required for digestion, absorption, transport, metabolism and storage of foods in the body. ➢ The SDA of proteins is primarily to meet the energy requirements for deamination, synthesis of urea, biosynthesis of proteins, synthesis of triacylglycerol (from carbon skeleton of amino acids). -

Measurement of Individual and Population Energetics of Marine Mammals

Marine Mammal Ecology and Conservation / 08-Boyd-Ch08 page 165 7:55pm OUP CORRECTED PROOF – Finals, 5/7/2010, SPi 8 Measurement of individual and population energetics of marine mammals Sara J. Iverson, Carol E. Sparling, Terrie M. Williams, Shelley L.C. Lang, and W. Don Bowen 8.1 Introduction The overriding currency of all animal life is energy. Animals have evolved strategies of energy acquisition and use, but these strategies also experience tradeoffs between energy allocated to maintenance, activities, growth, and reproduction and are central to our understanding of life histories and fitness. Thus ‘energetics’— the study of the metabolic requirements, energy use, and output of animals— underpins many areas of physiology, ecology, evolutionary, and population biology, and even ecosystem dynamics. Marine mammals pose many challenges for the study, interpretation, and com- parison of individual and population energetics. For instance, the ability to study captive animals is often restricted to a few of the smaller marine mammal species. Although opportunities in the wild may be greater, there remain serious limits to our abilities to study species in remote locations (e.g. polar bears, Ursus maritimus,in the high arctic), in unstable habitats (e.g. ice-associated pinnipeds in the Bering and Chukchi Seas), or due to endangered status (e.g. monk seals, Monachus spp., southern sea otters, Enhydra lutris nereis, and vaquita, Phocoena sinus). As a group, cetaceans pose further difficulties because of their limited accessibility and large size. Adaptive insulation (blubber) is important in temperature management (Iverson 2009a) and the presence of this comparatively inert tissue can add complexity to the issue of defining the metabolically relevant body mass in marine mammals. -

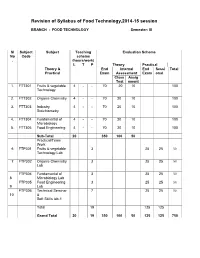

Revision of FT Syllabus Final

Revision of Syllabus of Food Technology,2014-15 session BRANCH : FOOD TECHNOLOGY Semester: III Sl Subject Subject Teaching Evaluation Scheme No Code scheme . (hours/work) L T P Theory Practical Theory & End Internal End Sessi Total Practical Exam Assessment Exam onal Class Assig Test nment 1. FTT301 Fruits & vegetable 4 - - 70 20 10 100 Technology 2. FTT302 Organic Chemistry 4 - - 70 20 10 100 3. FTT303 Industry 4 - - 70 20 10 100 Stoichiometry 4. FTT304 Fundamental of 4 - - 70 20 10 100 Microbiology 5. FTT305 Food Engineering 4 - - 70 20 10 100 Sub-Total 20 350 100 50 Practical/Team Work 6 FTP301 Fruits & vegetable 3 25 25 50 Technology Lab 7 FTP302 Organic Chemistry 3 25 25 50 Lab FTP304 Fundamental of 3 25 25 50 8 Microbiology Lab FTP305 Food Engineering 3 25 25 50 9 Lab FTP306 Technical Seminar 7 25 25 50 10 & Soft Skills lab-1 Total 19 125 125 Grand Total 20 19 350 100 50 125 125 750 FRUITS AND VEGETABLE TECHNOLOGY L T P 4 0 0 III/ FTT-301 Theory Exam. : 3 hrs. Total Contact hrs. : 60 Total Marks : 100 End Exam. : 70 Marks Theory : 60 I.A. : 20 Marks Practical : Nil Assignment : 10 Marks Objective As all the fruits & vegetable are seasonal, their storage, processing, preparation of fruits & vegetable products is highly essential. The students after completion of this paper is well concerned with the storage, preservation, processing & preparation of their products. They also will know details about the preparation of spice powder & condiment products. Topic wise distribution of periods Sl. -

Nutrition Courseware.Pdf

: : Biochemistry 211 SIBC Nutrition Chinnavuth Vatanashevanopakorn, M.D. Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University E-mail : [email protected] 1 Objective • สารอาหารและการจําแนกชนิดของสารอาหาร • Recommended Dietary Allowances • ความต้องการและการใช้พลังงานของร่างกาย • ความสําคัญของสารอาหารทีให้พลังงานทางด้านโภชนาการ • ภาวะโภชนาการและการประเมินภาวะโภชนาการ • สารพิษในอาหาร • บทบาทของอาหารในการส่งเสริมและป้องกันโรค 2 Nutrition • การศึกษาถึงความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างอาหารและสุขภาพของร่างกาย – ปริมาณและสัดส่วนของสารอาหารทีร่างกายควรได้รับ – การเปลียนแปลงของสารอาหารเพือการนําไปใช้ โดยผ่านขบวนการต่าง ๆ ตังแต่digestion, absorption, metabolism, transport, storage และ excretion • ความต้องการพลังงานและสารอาหารจะมีการเปลียนแปลงได้โดย ขึนกับ อายุ เพศ และสิงแวดล้อม 3 Food • สิงทีบริโภคแล้วไม่เป็นพิษ หรือก่อให้เกิดโทษแก่ร่างกาย • สามารถจําแนกออกเป็น 5 หมู่ – หมู่ที 1 เนือสัตว์ต่าง ๆ นม ไข่ และถัว – หมู่ที 2 ข้าว เผือก มัน และนําตาล – หมู่ที 3 ผักต่าง ๆ – หมู่ที 4 ผลไม้ต่าง ๆ – หมู่ที 5 ไขมัน และนํามันพืช 4 Nutrients (สารอาหาร) • ส่วนประกอบของอาหารทีจําเป็นต่อร่างกาย – สารทีให้พลังงาน – Essential molecules • แบ่งเป็น 2 กลุ่ม – Macronutrients : CHO, lipid and protein – Micronutrients : vitamins, minerals and water • หน้าทีของสารอาหาร – Providing energy : CHO, lipid (and protein) – Forming structures : lipid, protein and minerals – Regulating body processes : CHO, lipid, protein, vitamins, minerals and water 5 Nutrition recommendations • The first nutrition recommendations were made in the UK in the 1860s. • After -

2018-2019 Onwards)

Avinashilingam Institute for Home Science and Higher Education for Women (Deemed to be University under Category ‘A’ by MHRD, Estd. u/s 3 of UGC Act 1956) Re-accredited with ‘A’ Grade by NAAC. Recognised by UGC Under Section 12 B Coimbatore – 641043, Tamil Nadu, India B.Sc. Food Service Management and Dietetics Programme Specific Outcomes : 1. Know and understand scientific principle and techniques of food production in hospital dietaries and hospitality sector. 2. Comprehend and apply analytical principles of nutrients, food products, food quality and formulate diets. 3. Demonstrate effective utilization and management of resources. 4. Acquire skills in organization and management of hospital dietaries and food service institutions. 5. Become a successful entrepreneur, professional and pursue higher education. Scheme of instruction and examinations (For students admitted from 2018 -2019& onwards) Hours of Instruction /week Scheme of Examination Subject Name of paper / Part Duration Code component Theory Practical CIA CE Total Credit of exam First Semester Part I 18BLT001/1 Tamil - I Ilakiyam I, 5 - 3 50 50 100 4 8BLH001/18 Ilakanam, Ilakia BLF001 Varalaru/ Hindi – I Prose and non- detail test/ French – I Part II 18BLE001 English language 5 - 3 50 50 100 4 For communication I Part III Core Course 18BFDC01 Food Science 4 - 3 50 50 100 3 18BFDC02 Principles of Nutrition 4 - 3 50 50 100 3 18BFDC03 Food Science Practical - 3 3 50 50 100 2 18BFDC04 Principles of Nutrition - 4 3 50 50 100 2 Practical 1 18BFDI01 Discipline Specific 4 - 3 50 -

Appendix 1 Food and Nutrition Board, National Academy of Sciences-National Research Council Recommended Dietary Allowances, Revi

Appendix 1 Food and Nutrition Board, National Academy of Sciences-National Research Council Recommended Dietary Allowances, a Revised 1989 Designed for the maintenance of good nutrition of practically all healthy people in the United States Fat-Soluble Vitamins Water-Soluble Vitamins Minerals Vita- Vila- Vita- Vi",- Vi",- Thia- Ribo Vi", Fo- Vila CaI- PIIos- Magne- Sele Weight" Height" Age (years) Protein min A min D min E min K min C min flavin Niacin min 8 6 lale min 8 12 cium phoros sium Iron Zinc Iodine nium Category or Condition (kg) (Ib) (em) (in) (g) (II RE)' (lIg)" (mg a-n)' (lIg) (mg) (mg) (mg) (mg NE)' (mg) ()1g) (lIg) (mg) (mg) (mg) (mg) (mg) (mg) ()1g) Infants O.O-U.5 6 13 6U 24 13 375 7.5 30 ~ M 0.3 25 0.3 400 300 40 6 40 10 0.5-1.0 9 20 71 28 14 375 10 4 10 35 M ~ 0.6 35 0.5 600 500 60 10 50 IS Children 1-3 13 29 9U 35 16 400 (() 6 15 40 ~ U 9 1.0 50 0.7 800 800 80 10 10 70 20 4-6 20 44 112 44 24 sao \0 7 20 45 09 1.1 12 1.1 75 1.0 800 800 120 10 10 90 20 7-10 28 62 132 52 28 700 10 30 45 I~ 12 13 1.4 100 1.4 800 800 170 10 10 120 30 Males 11-14 45 99 157 62 4S 1000 10 10 45 SO 13 1.5 17 1.7 ISO 2.0 1200 1200 270 12 15 150 40 15-18 66 145 176 69 59 1000 \0 (() 65 60 1.5 1M 20 2.0 200 2.U 1200 1200 400 12 IS 150 50 19-24 72 160 177 70 58 1000 10 10 70 60 1.5 I~ 19 2.0 200 2.0 1200 1200 350 10 IS 150 70 25-50 79 174 176 70 63 1000 5 10 80 60 1.5 I~ 19 2.0 200 2.0 800 800 350 10 IS 150 70 ~ 51+ 77 170 173 68 63 1000 10 80 60 12 IA 15 2.0 200 2.0 800 800 350 10 IS 150 70 Females 11-14 46 101 IS7 62 46 800 10 45 50 1.1 1.3 -

Resting Metabolic Rate and Diet-Induced Thermogenesis

RESTING METABOLIC RATE AND DIET-INDUCED THERMOGENESIS studies in humans on individual differences and on the impact of nutritional and non-nutritional factors 0000 0330 1849 Promotor :dr .J.G.A.J .Hautvast , hoogleraari nd elee rva nd evoedin g end evoedselbereidin g Co-promotor:dr .P.R.M .Deurenberg , universitairhoofddocen t pMö[?-Ol , /^bO RESTING METABOLIC RATE AND DIET-INDUCED THERMOGENESI S studiesi n humans on individual differences and on the impact of nutritional and non-nutritional factors J.A. Weststrate Proefschrift terverkrijgin gva nd egraa dva n doctor ind e landbouwwetenschappen, opgeza gva nd erecto rmagnificus , dr.H.C .va nde rPlas , inhe topenbaa r teverdedige n opdinsdag 2 me i198 9 desnamiddag st evie ruu ri nd eaul a vand eLandbouwuniversitei t teWageninge n BIBLIOTHEEK LANDBOUWUNIVERSITEIT WAGEMNGE1V 'S* V-I Uo Aanmij nmoede r Financial supportb yUnileve r ResearchLaborator y for thepublicatio n of this thesis isgratefull y acknowledged. Stellingen 1.He t ontbreken van gegevens over de reproduceerbaarheid vanmetinge n van het thermogeen effect van voeding betekent niet, dat de reproduceerbaarheid van deze metingen goed is. (dit proefschrift) 2. De hoogte van de ruststofwisselingword t bij obese vrouwen mede bepaald door de lichaamsvetverdeling. (dit proefschrift) 3.D e hoogte van het thermogeen effect van voeding isbi jvrouwe n niet gerelateerd aan het lichaamsvetgehalte end e lichaamsvetverdeling. (dit proefschrift) 4.D e hoogte van het thermogeen effect van voeding hangt mede afva n factoren buiten de voeding. (dit proefschrift) 5.D e bevinding dat bij proefdieren onder normale omstandigheden het grootste deel van koolhydraten na vertering wordt omgezet invet , mag niet naar de mens worden geëxtrapoleerd. -

INTRODUCTION Which Is Referred to As the Specific Dynamic Action

Brit.J.Sports Med. - Vol. 21, No. 1, March 1987, pp. 27-28 27 PRE-EXERCISE FOOD AND HEART RATE DURING SUBMAXIMAL EXERCISE S. R. BIRD, PhD, MlBiol and S. HAY, BSc Br J Sports Med: first published as 10.1136/bjsm.21.1.27 on 1 March 1987. Downloaded from Christ Church College ofHigher Education, Canterbury ABSTRACT rhe heart rates of 20 movement studies students were measured during multi-stage cycle ergometer tests. The tests were repeated on five occasions following the ingestion of different pre-exercise meals and the results compared. A glucose solution taken three hours prior to the exercise (G3) resulted in the lowest heart rates at each work rate. The highest heart rates at each work rate were recorded following the ingestion of glucose or protein one hour before the exercise (G1 and P1 respectively). The heart rate values during G3 were on average 10.3 beat.min-1 lower than those used during G1 and P1. Intermediate heart rates were obtained with protein taken three hours prior to the exercise or a complete fast for 12 to 14 hours. The results have implications for those attempting to predict maximum oxygen uptake from submaximal heart rates. Key words: Specific Dynamic Action, Submaximal heart rates, Pre-exercise food. INTRODUCTION The pre-exercise dietary regimens were as follows; The Experiments conducted on resting individuals have shown first and last tests (F1 and F2) were undertaken following a that the ingestion of food and even the intravenous 12 to 14 hour overnight fast with no food being ingested on injection of nutrients will have a profound effect on the the morning of the test. -

Sugar Loss Attributed to Non-Enzymatic Browning Corresponds to Reduce Calories Recovered in Low-Molecular-Weight Fraction

ition & F tr oo u d N f S o c Liang et al., J Nutr Food Sci 2018, 8:2 l i e a n n r c DOI: 10.4172/2155-9600.1000674 e u s o J Journal of Nutrition & Food Sciences ISSN: 2155-9600 Research Article Open Access Sugar Loss Attributed to Non-Enzymatic Browning Corresponds to Reduce Calories Recovered in Low-Molecular-Weight Fraction Ningjian Liang1, Xiu-Min Chen2 and David D Kitts1* 1Food, Nutrition and Health Faculty of Land and Food Systems, University of British Columbia, Canada 2School of Food and Biological Engineering, Jiangsu University, P.R. China Abstract Health agencies state that total dietary energy intake should not exceed a maximal of 25% of calories derived from added sugars. Bakery products are major food sources that contribute to the added sugars intake; however potential sugars losses due to Maillard reaction and caramelization, occur at typical baking temperatures. In this study we employed markers associated with non-enzymatic browning, that corresponded to loss of free sugars, generation of α-dicarbonyl compounds with changes in caloric content of digestible constituents in sugar-amino acid model and cake formulations. Sugars losses in simple model systems that reached 100 percent after 40 min baking at baking temperatures of 150°C and 180°C corresponded to reduced calorie content, in fractions with a MW<3000 (p<0.05). In comparison, less gross energy calories from sucrose were lost after a similar heat treatment in sucrose- amino acid mixtures. Model cakes baked at 150°C and 180°C, respectively followed this trend with invert sugar, having greater losses losses (p<0.01) than cakes containing sucrose.