Bleeding Complications of Percutaneous Kidney Biopsy: Does Gender Matter?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urology Services in the ASC

Urology Services in the ASC Brad D. Lerner, MD, FACS, CASC Medical Director Summit ASC President of Chesapeake Urology Associates Chief of Urology Union Memorial Hospital Urologic Consultant NFL Baltimore Ravens Learning Objectives: Describe the numerous basic and advanced urology cases/lines of service that can be provided in an ASC setting Discuss various opportunities regarding clinical, operational and financial aspects of urology lines of service in an ASC setting Why Offer Urology Services in Your ASC? Majority of urologic surgical services are already outpatient Many urologic procedures are high volume, short duration and low cost Increasing emphasis on movement of site of service for surgical cases from hospitals and insurance carriers to ASCs There are still some case types where patients are traditionally admitted or placed in extended recovery status that can be converted to strictly outpatient status and would be suitable for an ASC Potential core of fee-for-service case types (microsurgery, aesthetics, prosthetics, etc.) Increasing Population of Those Aged 65 and Over As of 2018, it was estimated that there were 51 million persons aged 65 and over (15.63% of total population) By 2030, it is expected that there will be 72.1 million persons aged 65 and over National ASC Statistics - 2017 Urology cases represented 6% of total case mix for ASCs Urology cases were 4th in median net revenue per case (approximately $2,400) – behind Orthopedics, ENT and Podiatry Urology comprised 3% of single specialty ASCs (5th behind -

Native Kidney Biopsy

Mohammed E, et al., J Nephrol Renal Ther 2020, 6: 034 DOI: 10.24966/NRT-7313/100034 HSOA Journal of Nephrology & Renal Therapy Review Article Native Kidney Biopsy: An Introduction The burden of non communicable diseases has been a worldwide Update and Best Practice public health challenge, as chronic diseases compose 61% of global deaths and 49% of the global burden of diseases. Currently, many Evidence countries are encountering a fast transformation in the disease pro- file from first generation diseases such as infectious diseases to the encumbrance of non communicable diseases. In addition, Chronic Ehab Mohammed1, Issa Al Salmi1 *, Shilpa Ramaiah1 and Suad Hannawi2 Kidney Disease (CKD) is increasingly recognized as a global public health challenge as 10% of the global population is affected [1,2]. 1Nephrologist, The Renal Medicine Department, The Royal Hospital, Muscat, Oman The scarcity of well-trained renal pathologists, even in high-in- come countries, is a major obstacle to use of biopsy samples. The ISN 2Medicine Department, Ministry of Health and Prevention, Dubai, UAE is working worldwide to enhance development of local renal patholo- gy expertise. Levin et al stated that analysis of kidney biopsy samples can be used to stratify CKD into distinct subgroups of diseases based Abstract on specific histological patterns, when combined with the clinical pre- sentation [3]. Diabetes mellitus and hypertensive nephropathy are the Objectives: To Provide up-to-date guidelines for medical and nurs- commonly identified causes of End-Stage Kidney Disease (ESKD). ing staffs on the pre, during, and post care of a patient undergoing a Also, many patients with glomerulonephritis, systemic lupus erythe- percutaneous-kidney-biopsy-PKB. -

Percutaneous Ultrasound-Guided Renal Biopsy; a Comparison of Axial Vs

Percutaneous ultrasound-guided renal biopsy; A comparison of axial vs. sagittal probe location FARNAZ SHAMSHIRGAR1, SEYED MORTEZA BAGHERI2* 1Resident of Radiology, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran 2Department of Radiology, Hasheminejad Kidney Center (HKC), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran Background. Renal biopsy is an important method for diagnosis of renal parenchymal abnormalities. Here, we compare the effectiveness and complications of percutaneous ultrasound- guided renal biopsy using axial vs. sagittal probe locations. Methods. In a cross-sectional survey, in 2012, patients with a nephrologist order were biopsied by a radiology resident. Renal biopsy was done on 15 patients using axial (A group) and the same number of biopsies done with sagittal probe location (S group). The two groups were compared in term of the yields and complications of each method. Results. In the A group, the ratio of glomeruli gathered to the number of obtained samples was significantly higher than in the S group. Nine patients in the A group (60%) required only two samplings, whereas 66.7% in the S group required more than two attempts. Microscopic hematuria was more common in the A; conversely, gross hematuria was less common in the A group. Meagre hematomas were more frequent in the S group .When compared with hemoglobin level before biopsy, its level 24 hours after biopsy was similar within groups. Conclusion. Our study shows that percutaneous ultrasound-guided renal biopsy using axial probe provides better yield with fewer efforts and fewer serious complications. Keywords: Percutaneous renal biopsy, Ultrasound-guided renal biopsy, Ultra-sonography probe location. INTRODUCTION plications and related post therapeutic side effects may cause another complication such as vascular Percutaneous renal biopsy is an important occlusion, acute obstruction of renal output, renal method to diagnose most kidney diseases. -

Renal Scan Prior to Renal Biopsy—

RENAL SCAN PRIOR TO RENAL BIOPSY— A METHOD OF RENAL LOCALIZATION Richard J. Tully, Violet J. Stark, Paul B. Hoffer, and Alexander Gottschalk University of Chicago Hospitals and Clinics, and the A rgonne Cancer Research Hospital, Chicago, Illinois Palpation, percussion, and auscultation are the a generally lower radiation dose to the patient than classical methods of determining organ localization the radiographie procedures. One such technique— by external nontraumatic means. With the need for renal localization prior to renal biopsy—has become more specific information about smaller organs, espe routine at our institution in the last 6 years. cially for needle biopsy or aspiration techniques, more definitive localization of these organs has be METHODS come necessary. The anatomic landmarks used in In our method (7) the patient is given an injection most biopsy techniques are simply not specific of 1.0 mCi of Tc-Fe-ascorbic acid complex and enough to cover individual variation. This has led about 1 hr later is positioned under the gamma cam- to the development of many radiographie procedures and more recently to the use of radionuclide dis Received Oct. 28, 1971; revision accepted Mar. 2, 1972. tribution or ultrasonography for localization. The For reprints contact: Richard J. Tully, University of Chicago, Dept. of Radiology, 950 E. 59 St., Chicago, 111. latter procedures are desirable because they deliver 60637. FIG. 1. A shows patient positioned under camera 1 hr after injection of 0.1 mCi Tc-Fe-ascorbic acid complex in "bi opsy position". B shows small point sources ("Co) positioned on patient's back until they coincide with scan image of renal out line by trial and error method or with use of persistence oscilloscope. -

Icd-9-Cm (2010)

ICD-9-CM (2010) PROCEDURE CODE LONG DESCRIPTION SHORT DESCRIPTION 0001 Therapeutic ultrasound of vessels of head and neck Ther ult head & neck ves 0002 Therapeutic ultrasound of heart Ther ultrasound of heart 0003 Therapeutic ultrasound of peripheral vascular vessels Ther ult peripheral ves 0009 Other therapeutic ultrasound Other therapeutic ultsnd 0010 Implantation of chemotherapeutic agent Implant chemothera agent 0011 Infusion of drotrecogin alfa (activated) Infus drotrecogin alfa 0012 Administration of inhaled nitric oxide Adm inhal nitric oxide 0013 Injection or infusion of nesiritide Inject/infus nesiritide 0014 Injection or infusion of oxazolidinone class of antibiotics Injection oxazolidinone 0015 High-dose infusion interleukin-2 [IL-2] High-dose infusion IL-2 0016 Pressurized treatment of venous bypass graft [conduit] with pharmaceutical substance Pressurized treat graft 0017 Infusion of vasopressor agent Infusion of vasopressor 0018 Infusion of immunosuppressive antibody therapy Infus immunosup antibody 0019 Disruption of blood brain barrier via infusion [BBBD] BBBD via infusion 0021 Intravascular imaging of extracranial cerebral vessels IVUS extracran cereb ves 0022 Intravascular imaging of intrathoracic vessels IVUS intrathoracic ves 0023 Intravascular imaging of peripheral vessels IVUS peripheral vessels 0024 Intravascular imaging of coronary vessels IVUS coronary vessels 0025 Intravascular imaging of renal vessels IVUS renal vessels 0028 Intravascular imaging, other specified vessel(s) Intravascul imaging NEC 0029 Intravascular -

Post-Percutaneous Renal Biopsy Observation Time; Single Center Experience

Open Access Austin Journal of Nephrology and Hypertension Special Article - Chronic Kidney Disease Post-Percutaneous Renal Biopsy Observation Time; Single Center Experience Habas E1*, Elhabash B2, Rayani A3, Turgman F4 and Tarsien R2 Abstract 1 Department of Internal Medicine, Tripoli Central Background: Percutaneous Renal Biopsy (PRB) should be performed Hospital, Libya to diagnose renal damage, to assess response to treatment and to predict 2Department of Rheumatology, Tripoli Medical Center, prognosis.PRB is a safer procedure and mostly free of complications. Assessing Libya optimal time duration post-PRB is important to predict Post-PRB complication 3Department of Pediatrics, Tripoli Children Hospital, and to reduce the cost of PRB. Pediatric Arab Board, Libya 4Pathologist, Tripoli Central Hospital, University of Aim: To reduce the Post-PRB observation time for optimal outcome and Tripoli, Libya patient’s safety. *Corresponding author: Elmukhtar Habas, Methods: All PRBs were performed at the Nephrology Unit, Tripoli Department of Internal Medicine, Tripoli Central Central Hospital, Libya between May 2008 to December 2015. One hundred Hospital, Facharzt Nephrology, Libya eighteen ultrasound-guided PRBs were done. After explaining the procedure and its possible complications, an informed consent was signed by patients. Received: July 01, 2016; Accepted: August 23, 2016; Coagulation profile PT, PTT, INR, BT, CT and CBC were done before PRB. Published: August 25, 2016 Each biopsy was performed with an automated biopsy gun with a 16 -gauge needle under real-time US. Two biopsy specimens from lower pole of left kidney were taken from native kidneys. All patients were kept under close medical supervision and on bed rest for 2-hours. -

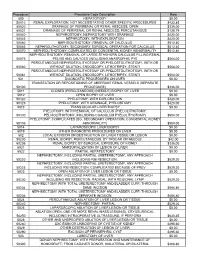

Procedure Procedure Code Description Rate 500

Procedure Procedure Code Description Rate 500 HEPATOTOMY $0.00 50010 RENAL EXPLORATION, NOT NECESSITATING OTHER SPECIFIC PROCEDURES $433.85 50020 DRAINAGE OF PERIRENAL OR RENAL ABSCESS; OPEN $336.00 50021 DRAINAGE OF PERIRENAL OR RENAL ABSCESS; PERCUTANIOUS $128.79 50040 NEPHROSTOMY, NEPHROTOMY WITH DRAINAGE $420.00 50045 NEPHROTOMY, WITH EXPLORATION $420.00 50060 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; REMOVAL OF CALCULUS $512.40 50065 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; SECONDARY SURGICAL OPERATION FOR CALCULUS $512.40 50070 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; COMPLICATED BY CONGENITAL KIDNEY ABNORMALITY $512.40 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; REMOVAL OF LARGE STAGHORN CALCULUS FILLING RENAL 50075 PELVIS AND CALYCES (INCLUDING ANATROPHIC PYE $504.00 PERCUTANEOUS NEPHROSTOLITHOTOMY OR PYELOSTOLITHOTOMY, WITH OR 50080 WITHOUT DILATION, ENDOSCOPY, LITHOTRIPSY, STENTI $504.00 PERCUTANEOUS NEPHROSTOLITHOTOMY OR PYELOSTOLITHOTOMY, WITH OR 50081 WITHOUT DILATION, ENDOSCOPY, LITHOTRIPSY, STENTI $504.00 501 DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES ON LIVER $0.00 TRANSECTION OR REPOSITIONING OF ABERRANT RENAL VESSELS (SEPARATE 50100 PROCEDURE) $336.00 5011 CLOSED (PERCUTANEOUS) (NEEDLE) BIOPSY OF LIVER $0.00 5012 OPEN BIOPSY OF LIVER $0.00 50120 PYELOTOMY; WITH EXPLORATION $420.00 50125 PYELOTOMY; WITH DRAINAGE, PYELOSTOMY $420.00 5013 TRANSJUGULAR LIVER BIOPSY $0.00 PYELOTOMY; WITH REMOVAL OF CALCULUS (PYELOLITHOTOMY, 50130 PELVIOLITHOTOMY, INCLUDING COAGULUM PYELOLITHOTOMY) $504.00 PYELOTOMY; COMPLICATED (EG, SECONDARY OPERATION, CONGENITAL KIDNEY 50135 ABNORMALITY) $504.00 5014 LAPAROSCOPIC LIVER BIOPSY $0.00 5019 OTHER DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES -

Table S1. Possible Indications for Renal Biopsy. Indications

Table S1. Possible indications for renal biopsy. indications Microscopic haematuria Urologically unexplained macroscopic haematuria Proteinuria Nephrotic syndrome Impaired kidney function Hypertension Possible renal involvement in systemic disease in: multiple myeloma monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance systemic lupus erythematosus antiphospholipid syndrome diabetes systemic vasculitis scleroderma Table S2. Contraindications to renal biopsy Contraindication Reason Relative: Hypertension Poorly controlled hypertension thought to increase risk of bleeding Renal asymmetry Suggestive of a process causing differential loss of renal mass (eg reflux nephropathy, atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis – although both these can cause proteinuria) Decreased renal size Suggestive of chronic (therefore irreversible) renal (usually assessed as damage, predictive of nonspecific fibrotic changes on bipolar length on biopsy ultrasound) Increased risk of complications reported in most series. Single kidney Accepted wisdom, based on the fact that the patient will be put into renal failure if there is irreversible damage to the kidney; however, if the patient appears likely to go into renal failure if left untreated, there is less to lose, and a biopsy may be justified if it might disclose a treatable condition Unco-operative patient Increased risk of complications if the patient cannot reliably stop breathing during needle puncture. Consider alternatives including biopsy under general anaesthetic, transvenous biopsy Hydronephrosis Obstructive -

Use of Ultrasound in Kidney Disease and Nephrology Procedures

CJASN ePress. Published on January 23, 2014 as doi: 10.2215/CJN.03170313 Renal Relevant Radiology: Use of Ultrasound in Kidney Disease and Nephrology Procedures W. Charles O’Neill Abstract Ultrasound is commonly used in nephrology for diagnostic studies of the kidneys and lower urinary tract and to guide percutaneous procedures, such as insertion of hemodialysis catheters and kidney biopsy. Nephrologists must, therefore, have a thorough understanding of renal anatomy and the sonographic appearance of normal Renal Division, Department of kidneys and lower urinary tract, and they must be able to recognize common abnormalities. Proper interpretation Medicine, Emory requires correlation with the clinical scenario. With the advent of affordable, portable scanners, sonography has University School of become a procedure that can be performed by nephrologists, and both training and certification in renal Medicine, Atlanta, ultrasonography are available. Georgia Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: ccc–ccc, 2014. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03170313 Correspondence: Dr.W.Charles O’Neill, Emory Introduction decisions (Figure 1). Given its poor precision (5), this University School of Sonography is an essential tool in nephrology for not measurement should be performed several times. Medicine, Renal only the diagnosis and management of kidney dis- Since the poor precision stems mostly from under- Division WMB 338, 1639 Pierce Drive, ease, but also for the guidance of invasive procedures. measurement, the maximum length is the value that Atlanta, GA 30322. For this reason, it is essential for nephrologists to should be reported. Measurement of other dimen- Email: woneill@ have a thorough understanding of sonography and its sionsisevenmoreimpreciseandisofnoutility. emory.edu uses in nephrology. -

Renal Biopsy

Renal Biopsy What is a renal biopsy? A renal biopsy is a procedure that takes a sample of kidney tissue for testing. A renal biopsy may also be done to identify a problem with the kidney or to check why a kidney transplant is not working well. Is there anything I have to do before the biopsy? You will sign a consent form for the biopsy. There are no changes in your diet before this test. If you are in Inpatient: You will have blood tests done before this procedure. If you take blood thinning medication such as warfarin, coumadin or aspirin, you will need to have this adjusted before the biopsy. Talk to your nurse or doctor if you are taking these medications. If you are an outpatient: You will have blood tests done in the Outpatient Laboratory. If you take blood thinning medication such as warfarin, coumadin or aspirin, you will need to have this adjusted before the biopsy. Talk to your doctor well before the procedure if you are taking these medications. What happens the day of the biopsy? If you are in Inpatient: You will get ready for the procedure on the patient care unit. You may have an intravenous called an IV started. This is a thin tube put into a vein in your arm to give you fluids and medication before during and after the procedure. You are then taken to have your procedure on a stretcher. If you are an outpatient: You come to the Day Surgery Unit at St. Joseph’s Hospital. -

Renal Biopsy: Clinical Correlations November 9, 4:30-6:30 P.M

Renal Biopsy: Clinical Correlations November 9, 4:30-6:30 p.m. 20 19 Washington, DC Nov. 5–10 ASN Kidney Week 2019 – Renal Biopsy: Clinical Correlations (Full Syllabus) Case 1 from Kammi J. Henriksen, MD – University of Chicago A 50-year-old man with HIV infection (currently with an undetectable viral load), human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) infection, Kaposi sarcoma, and multicentric Castleman disease presented with 2 weeks of fatigue, vomiting, and anorexia. He had recently completed a course of trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole for cellulitis. Notably, he was diagnosed with HIV infection 13 years prior to admission. He was started on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) with a tenofovir-containing regimen 10 years after the diagnosis of HIV. Despite treatment, his CD4 levels remained low (100-200/µL). His HIV infection was complicated by multicentric Castleman disease, which was diagnosed 1 year prior to admission when the patient presented with fever and bilateral axillary adenopathy. Lymph node biopsy at that time showed follicular hyperplasia with HHV-8–positive cells. On admission, physical examination was significant for dry mucous membranes, sinus tachycardia, and a diffuse papular rash over his torso and extremities consistent with Kaposi sarcoma. Workup was significant for severe hyponatremia, AKI, and microscopic hematuria with dysmorphic red blood cells (RBCs). Laboratory findings were as follows: Serum Sodium 103 mEq/L Creatinine 3.7 mg/dL (previous baseline 0.9 mg/dL) HHV-8 33,700 copies/mL IL-6 83.2 pg/mL ANCA Negative Antinuclear antibodies Negative C3/C4 Negative Urine 24-Hour protein 2.1 g Urine sediment microscopy with renal tubular epithelial cells, granular casts, and RBCs. -

Renal Biopsy Collection Instructions

Saint Louis University Histopathology Department 1402 South Grand Blvd. St. Louis, MO 63104 Phone: 314-977-7874 Fax: 314-977-7898 Renal Biopsy Collection Instructions Purpose: To ensure proper handling and transport of renal biopsy specimens for Light Microscopy (LM), Immunofluorescence (IF), and Electron Microscopy (EM). Principle: Renal biopsies, also known as kidney biopsies, are performed to aid in the diagnosis of suspected kidney problems, determine the severity of the pathologic process, and to aid in determining the optimal treatment. Renal biopsies are also performed to monitor how well a transplanted kidney is functioning and/or to identify the early signs of rejection. They can be obtained by percutaneous needle biopsy or by ‘open’ wedge biopsy. --- Safety --- Be sure to follow all universal precautions when handling any kind of fresh tissue. There are two options when handling renal biopsies. They are listed in order of preference: Preferred Method: NOTE: Time of collection to time of receipt in lab should not be greater than 2 hours. • Place biopsy on saline moistened telfa (NOT gauze) or on a glass slide, inside a specimen container. o Ensure that the container is labeled with two patient identifiers, the location of the biopsy, and the collection time. • Place the container in a biohazard bag with a cold pack or ice. Place bag inside a larger plastic container or box and send to the Histopathology Laboratory via the quickest transport method. o Note: The transport container should not be a padded envelope. • Include a “Fresh Tissue/Electron Microscopy” specimen requisition which can be found on the SLUCare Department of Pathology website.