Concepts of Childhood: What We Know and Where We Might Go

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction: the Western Concept of Childhood

Introduction: The Western Concept of Childhood Laurence Brockliss As the great European powers, and to a lesser extent the United States, became predominant commercially and militarily across the globe after 1850, the rest of the world came to see Western culture in all its many different forms as an ideal that had to be imitated and absorbed if colonization and domination by outsiders were ever to be overthrown or withstood. This was as true of concep- tions of childhood and child-rearing as anything else. In the Middle Ages European children had been largely seen as fallen, wilful and incomplete crea- tures whose socialization into adulthood was left to their parents and was a matter of custom. By the late nineteenth century, among most of the well-to- do at least, children were seen as fragile, innocent vessels: their upbringing required expert advice to be successfully negotiated and was the responsibility of the state as well as the family.1 Any history of children and child-rearing in the non-Western world in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries will inevitably have as its backdrop the impact of this still freshly minted idea of childhood on traditional beliefs and practices. At the same time, the influ- ence of Western ideas on any narrative of non-Western childhoods in the decades before and after the First World War will be far from straightforward. Importing the Western concept of childhood into traditional societies and cul- tures was inevitably a Herculean task. The supporters of modernization usu- ally lacked the money and the authority to enforce their will, while many of the modernizers were understandably ambivalent about unreservedly introducing the alien ideas of the imperialists into their native land, even if they believed there was a need to re-structure traditional beliefs. -

The Pulpits and the Damned

THE PULPITS AND THE DAMNED WITCHCRAFT IN GERMAN POSTILS, 1520-1615 _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by TANNER H. DEEDS Dr. John M. Frymire, Thesis Advisor DECEMBER 2018 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled THE PULPITS AND THE DAMNED: WITCHCRAFT IN GERMAN POSTILS, 1520- 1615 presented by Tanner H. Deeds a candidate for the degree of Master of Arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor John M. Frymire Professor Kristy Wilson-Bowers Professor Rabia Gregory I owe an enormous debt to my entire family; but my greatest debt is to my maternal grandmother Jacqueline Williams. Her love and teachings were instrumental in making me who I am today. Unfortunately, she passed away during the early stages of this project and is unable to share in the joys of its completion. My only hope is that whatever I become and whatever I accomplish is worthy of the time, treasure, and kindness she gave me. It is with the utmost joy and the most painful sorrow that I dedicate this work to her. ACKNOWLEGEMENTS At both the institutional and individual level, I have incurred more debts than I can ever hope to repay. Above all I must thank my advisor Dr. John Frymire. Dr. Frymire has been an exemplar advisor from my first day at the University of Missouri. Both in and out of the classroom, he has taught me more than I could have ever hoped when I began this journey. -

Jeder Treu Auf Seinem Posten: German Catholics

JEDER TREU AUF SEINEM POSTEN: GERMAN CATHOLICS AND KULTURKAMPF PROTESTS by Jennifer Marie Wunn (Under the Direction of Laura Mason) ABSTRACT The Kulturkampf which erupted in the wake of Germany’s unification touched Catholics’ lives in multiple ways. Far more than just a power struggle between the Catholic Church and the new German state, the conflict became a true “struggle for culture” that reached into remote villages, affecting Catholic men, women, and children, regardless of their age, gender, or social standing, as the state arrested clerics and liberal, Protestant polemicists castigated Catholics as ignorant, anti-modern, effeminate minions of the clerical hierarchy. In response to this assault on their faith, most Catholics defended their Church and clerics; however, Catholic reactions to anti- clerical legislation were neither uniform nor clerically-controlled. Instead, Catholics’ Kulturkampf activism took many different forms, highlighting both individual Catholics’ personal agency in deciding if, when, and how to take part in the struggle as well as the diverse factors that motivated, shaped, and constrained their activism. Catholics resisted anti-clerical legislation in ways that reflected their personal lived experience; attending to the distinctions between men’s and women’s activism or those between older and younger Catholics’ participation highlights individuals’ different social and communal roles and the diverse ways in which they experienced and negotiated the dramatic transformations the new nation underwent in its first decade of existence. Investigating the patterns and distinctions in Catholics’ Kulturkampf activism illustrates how Catholics understood the Church-State conflict, making clear what various groups within the Catholic community felt was at stake in the struggle, as well as how external factors such as the hegemonic contemporary discourses surrounding gender roles, class status, age and social roles, the division of public and private, and the feminization of religion influenced their activism. -

1 Introduction

1Introduction The expanding world of Children’s Literature Studies Peter Hunt So what good is literary theory? Will it keep our children singing? Well perhaps not. But understanding something of literary theory will give us some understanding of how the literature we give to our children works. It might also keep us engaged with the texts that surround us, keep us singing even if it is a more mature song than we sang as youthful readers of texts. As long as we keep singing, we have a chance of passing along our singing spirit to those we teach. (McGillis 1996: 206) Children’s literature ‘Children’s literature’ sounds like an enticing field of study; because children’s books have been largely beneath the notice of intellectual and cultural gurus, they are (apparently) blissfully free of the ‘oughts’: what we ought to think and say about them. More than that, to many readers, children’s books are a matter of private delight, which means, perhaps, that they are real literature – if ‘literature’ consists of texts which engage, change, and provoke intense responses in readers. But if private delight seems a somewhat indefensible justification for a study, then we can reflect on the direct or indirect influence that children’s books have, and have had, socially, culturally, and historically. They are overtly important educationally and commer- cially – with consequences across the culture, from language to politics: most adults, and almost certainly the vast majority of those in positions of power and influence, read chil- dren’s books as children, and it is inconceivable that the ideologies permeating those books had no influence on their development. -

The Christian Movement in the Second and Third Centuries

WMF1 9/13/2004 5:36 PM Page 10 The Christian Movement 1 in the Second and Third Centuries 1Christians in the Roman Empire 2 The First Theologians 3Constructing Christian Churches 1Christians in the Roman Empire We begin at the beginning of the second century, a time of great stress as Christians struggled to explain their religious beliefs to their Roman neighbors, to create liturgies that expressed their beliefs and values, and to face persecution and martyrdom cour- ageously. It may seem odd to omit discussion of the life and times of Christianity’s founder, but scholarly exploration of the first century of the common era is itself a field requiring a specific expertise. Rather than focus on Christian beginnings directly, we will refer to them as necessitated by later interpretations of scripture, liturgy, and practice. Second-century Christians were diverse, unorganized, and geographically scattered. Paul’s frequent advocacy of unity among Christian communities gives the impression of a unity that was in fact largely rhetorical. Before we examine Christian movements, however, it is important to remind ourselves that Christians largely shared the world- view and social world of their neighbors. Polarizations of “Christians” and “pagans” obscure the fact that Christians were Romans. They participated fully in Roman culture and economic life; they were susceptible, like their neighbors, to epidemic disease and the anxieties and excitements of city life. As such, they were repeatedly shocked to be singled out by the Roman state for persecution and execution on the basis of their faith. The physical world of late antiquity The Mediterranean world was a single political and cultural unit. -

Bible/Book Studies

1 BIBLE/BOOK STUDIES A Gospel for People on the Journey Luke Novalis Scripture Studies Series Each of the writers of the Gospels has his particular vision of Jesus. For Luke, Jesus is not only the one who announces the Good News of salvation: Jesus is our salvation. 9 copies Editor: Michael Trainor A Gospel for Searching People Matthew Novalis Scripture Studies Series Each of the writers of the Gospels has his particular vision of Jesus. For Matthew, Jesus is the great teacher (Matt. 23:8). But teacher and teachings are inextricable bound together, Matthew tells us. Jesus stands alone as unique teacher because of his special relationship with God: he alone is Son of man and Son of God. And Jesus still teaches those who are searching for meaning and purpose in life today. 9 copies Editor: Michael Trainor A Gospel for Struggling People Mark Novalis Scripture Studies Series “Who do you say that I am? In Mark’s Gospel, no one knows who Jesus is until, in Chapter 8, Peter answers: “You are the Christ.” But what does this mean? The rest of the Gospel shows what kind of Christ or Messiah Jesus is: he has come to suffer and die for his people. Teaching on discipleship and predictions of his death point ahead to the focus of the Gospel-the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus. 9 copies Editor: Michael Trainor Beautiful Bible Stories Beautiful Bible Stories by Rev. Charles P. Roney, D.D. and Rev. Wilfred G. Rice, Collaborator Designed to stimulate a greater interest in the Bible through the arrangement of extensive References, Suggestions for Study, and Test Questions. -

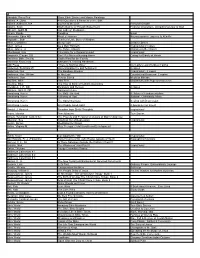

St. Barbara's Lending Library 2016.Xlsx

A Abradale Press Pub. Great Bible Stories and Master Paintings Adams, A. Dana 4000 Questions & Answers on the Bible Adams ,Kathleen, MA Journal to the Self Personal Growth Adams, Scott God's Debris: A Thought Experiment Fictional Characters, Untraditional view of God Albright, Judith M, Our Lady of Medjugorje Alcorn, Randy Deadline Novel Alexander, Eben MD Proof of Heaven Neurosurgeon's Journey to Afterlife Algozzine, Bob Teacher's Little Book of Wisdom Allen, Constance Sleep Tight Sesame Street Allen, James As a Man Thinketh Inspirational 2 copies Allen, John L. Jr The Future Church Changes in the Church Allenbaugh, Kay Chocolate for a Woman's Heart Inspirational Amarnick, Claude, DO Don't Put Me in a Nursing Home Caring for Elderly at Home American Bible Society God's Word for the Family American Red Cross Babysitter's Training Handbook AMI Press "There Is Nothing More" Our Lady's Last Words at Fatima Anderson, Bernhard W. Understanding the Old Testament 2 copies Anderson, Neil The Bondage Breaker Inspirational - 2 copies Anderson, Rev. William In His Light Catechetical Resource 2 copies Andriacco, Dan Screen Saved Media in Ministry Aquilina, Mike Take Five Meditations with Pope Benedict XVI Aquilina, Mike The How to Book of Catholic Devotions Arendzen, J. P., DD Purgatory and Heaven 2 copies Arintero, John G, OP Holiness Is Love Armstrong, Karen The Battle for God A History of Fundamentalism Armstrong, Karen A History of God Judaism, Christianity, Islam Armstrong, Karen The Spiral Staircase Dealing with Depression Armstrong, Louise Kiss Daddy Good-night A Speak-out on Incest Arnold, J. -

Western Kentucky Catholic 600 Locust Street Nonprofit Org

Western Kentucky Catholic 600 Locust Street Nonprofit Org. Owensboro, Kentucky 42301 U.S. Postage Western Kentucky Paid Owensboro, KY Permit No. 111 Change Service Requested 42301 Volume 28, Number 7 CATHOLIC The Roman Catholic Diocese of Owensboro, Kentucky September, 2001 To give or not to give Bishop John McRaith invites you The Bishop annually asks us this question to the Diaconate during the Disciples Response Fund Appeal Ordination The signs of the giving season are here. Disciples Response Fund Contributors of Mr. Mark Disciples Response Fund materials are are listed inside this edition of the being mailed to homes across the diocese. Western Kentucky Catholic Buckner Every parish will read the Bishop’s remark at St. Stephen Cathedral from the pulpit by September 9th. And this it accomplishes great things for the Catholic 12:05 p.m., Noon Mass, issue of the Western Kentucky Catholic has Church of Western Kentucky. I realize that October 20, 2001 printed the names of nearly 5000 donors to people are asked on a continual basis for Mark is the son of Joseph the annual Disciples Response Fund Ap- money, but then I am too. All that I ask is that and Claudine Blandford of we prayerfully consider what God has en- peal. It’s time to consider giving again. St. Stephen Parish, The Disciples Response Fund is the an- trusted to our care, and share some of that Owensboro, and is enrolled nual diocesan effort that encourages homes portion with these important efforts. to make generous financial contributions to “When people look at the way we do in Sacred Heart Seminary Mark Buckner diocesan efforts of outreach, education and business they know we carefully steward School of Theology, evangelization. -

Father Bob Vaillancourt to Take Over Midcoast Parish by Judy Harrison April 18, 2016

Father Bob Vaillancourt to take over midcoast parish by Judy Harrison April 18, 2016 ROCKLAND, Maine — The priest who led the Maine delegation to World Youth Day 2002 in Toronto, the last time Pope John Paul II visited North America before his death, will take over leadership of a midcoast parish that stretches from Camden to Belfast and includes two islands. The Rev. Robert C. Vaillancourt, 62, a Lewiston native, will become pastor of St. Brendan the Navigator Parish June 1. The parish includes Catholic churches in Camden, Rockland, Belfast, Islesboro and Vinalhaven. The Roman Catholic diocese of Portland announced the assignment in a news release issued Sunday. While his title on the Toronto trip was spiritual director, “Father Bob” also functioned as tour guide, cheerleader, water boy and dispenser of vital information to many of the 350 young people and their chaperones who went to see Pope John Paul II. The priest also has been known to sing an entire Mass. Vaillancourt has served since 2013 as a hospital chaplain at Maine Medical Center and Mercy Hospital, both in Portland, with weekend duties at the Parish of the Holy Eucharist in Falmouth. He graduated from St. Dominic Regional High School before earning a bachelor’s degree in psychology from the University of Maine in Orono and another in theology from St. Paul University in Ottawa. He was ordained to the priesthood by Bishop Edward C. O’Leary on Aug. 14, 1982, at what is now the Basilica of St. Peter and Paul in Lewiston. Over the years, he has served at parishes in Biddeford, Madawaska, East Millinocket, Old Town, Hampden, Winterport and Rumford. -

Children's Literature Grows Up

Children's Literature Grows Up The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Mattson, Christina Phillips. 2015. Children's Literature Grows Up. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17467335 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Children’s Literature Grows Up A dissertation presented by Christina Phillips Mattson to The Department of Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Comparative Literature Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May, 2015 © 2015 Christina Phillips Mattson All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Maria Tatar Christina Phillips Mattson Abstract Children’s Literature Grows Up proposes that there is a revolution occurring in contemporary children’s fiction that challenges the divide that has long existed between literature for children and literature for adults. Children’s literature, though it has long been considered worthy of critical inquiry, has never enjoyed the same kind of extensive intellectual attention as adult literature because children’s literature has not been considered to be serious literature or “high art.” Children’s Literature Grows Up draws upon recent scholarship about the thematic transformations occurring in the category, but demonstrates that there is also an emerging aesthetic and stylistic sophistication in recent works for children that confirms the existence of children’s narratives that are equally complex, multifaceted, and worthy of the same kind of academic inquiry that is afforded to adult literature. -

Cristo Rey Graduates First Class Virus Devastates Families

THE CATHOLIC PAGE 16 Pro-life Billboard June 5, 2020ommentator Vol. 58, No. 9 2019 LPA GENERAL EXCELLENCE AWARD RECIPIENT thecatholiccommentator.org C ‘RESILIENT GROUP’ Cristo Rey graduates From the Bishop first class Bishop Michael G. Duca By Richard Meek The Catholic Commentator Change Where flood waters once threatened to wash away dreams, hope emerged through under a brilliant sun seemingly beam- ing its approval. Bookended by a catastrophic flood, listening 18 months in windowless classrooms and finally, the coronavirus pandemic, his week, we as a nation, the inaugural graduating class of Cris- watched the horrific and to Rey Baton Rouge Franciscan High heart breaking death of Mr. Cristo Rey Baton Rouge Franciscan High School celebrated its inaugural graduating T School celebrated in an emotional out- George Floyd while being subdued class with an outdoor ceremony. Smiles were evident as the graduates walked from door ceremony. Family members and by police in Minneapolis. (Before the football field where a class photo was taken to the area where the cars were friends, all in their automobiles, parked you read on, remember now what parked and family members awaiting. Photo by Richard Meek | The Catholic Commentator in front of the stage, the blaring sounds your first feelings were when you of horns expressing their congratula- read this first sentence.) tions and pride. pandemic) but God always has a plan. Catholic education with the unique op- We can view this as an isolated “We are the resilient group; we per- “The difficult times shaped us for who portunity of working in the corporate event, but even then, it is by any severed, did not quit and overcame,” we are today.” world for one day a week, an idea en- measure of human common de- salutatorian Bria Coleman said. -

Archgm News the Official Newsletter of the Archdiocese of Grouard-Mclennan

MAY 2021 ARCHGM NEWS THE OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE ARCHDIOCESE OF GROUARD-MCLENNAN IN THIS ISSUE ARCHBISHOP PETTIPAS' CONVERSATIONS WITH BERTHA FATHER FEROZ BIDS FAREWELL EL SHADDAI CELEBRATES SIX YEARS IN GRANDE PRAIRIE REMEMBERING ST. KATERI'S CANONIZATION LITURGICAL NOTES REFLECTION ON ST JOSEPH THE WORKER The Northern Lights glisten over St. Joseph ...AND MUCH MORE Church in John D'or Prairie. TABLE OF CONTENTS News Bulletin - pg 3 A brief round-up of news in our Archdiocese and the Church around the world Conversations with Bertha - pg 5 The first installment in a new series by Archbishop Gerard Pettipas Father Feroz bids farewell - pg 9 Passionate priest reflects on his three years in northern Alberta A growing faith - pg 12 El Shaddai celebrates six years in Grande Prairie Community - pg 14 The latest updates from our parishes 'It's like a dream' - pg 17 Missionary nun and Indigenous Catholic fondly remember their pilgrimage for St. Kateri Liturgical Notes - pg 20 Archbishop Pettipas discusses some of the important liturgical feasts this month Editor's reflection: St. Joseph the Worker - pg 21 How Christianity transformed the meaning of work Archbishop's Calendar - pg 24 See where the Archbishop will be over the next month Birthdays and Anniversaries - pg 25 Our priests and staff celebrating anniversaries this May PAGE 02 news bulletin New Mass restrictions As of May 5, Mass will now be limited to 15 people or 10% of firecode capacity – whichever is less - in all parishes in the Archdiocese. Funerals and weddings can have a maximum of 10 people, including all participants and guests.