The Pulpits and the Damned

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Handout 2F: Reflection

Ending Poverty In Community A Toolkit for Young Advocates Name _____________________________________________ Date ____________ Handout 2F: Reflection Directions: Reflect on the quotations below. On the back of this handout, write a portion of a quotation that you find particularly meaningful. How is God calling you to help tear down the “wall of poverty?” “This, rather, is the fasting that I wish: releasing those bound unjustly, untying the thongs of the yoke; Setting free the oppressed, breaking every yoke; Sharing your bread with the hungry, sheltering the oppressed and the homeless; Clothing the naked when you see them, and not turning your back on your own.” --Isaiah 58:6-7 “I know that you as young people have great aspirations, that you want to pledge yourselves to build a better world. Let others see this, let the world see it.” - Pope Benedict XVI, Homily at World Youth Day, 2005 “The direct duty to work for a just ordering of society . is proper to the lay faithful. As citizens of the State, they are called to take part in public life in a personal capacity. The mission of the lay faithful is therefore to configure social life correctly.” -- Pope Benedict XVI, God is Love, 2005, no. 29 “A society of genuine solidarity can be built only if…we consider it an honor to be able to devote our care and attention to the needs of our brothers and sisters in difficulty…. Those living in poverty can wait no longer. They need help now….” -- Pope John Paul II, Message for World Day of Peace, January 1, 1998, no. -

SACRAMENTAL THEOLOGY and ECCLESIASTICAL AUTHORITY Dmusjankiewicz Fulton College Tailevu, Fiji

Andn1y.r Uniwr~itySeminary Stndics, Vol. 42, No. 2,361-382. Copyright 8 2004 Andrews University Press. SACRAMENTAL THEOLOGY AND ECCLESIASTICAL AUTHORITY DmusJANKIEWICZ Fulton College Tailevu, Fiji Sacramental theology developed as a corollary to Christian soteriology. While Christianity promises salvation to all who accept it, different theories have developed as to how salvation is obtained or transmitted. Understandmg the problem of the sacraments as the means of salvation, therefore, is a crucial soteriological issue of considerable relevance to contemporary Christians. Furthermore, sacramental theology exerts considerable influence upon ecclesiology, particularb ecclesiasticalauthority. The purpose of this paper is to present the historical development of sacramental theology, lea- to the contemporary understanding of the sacraments within various Christian confessions; and to discuss the relationship between the sacraments and ecclesiastical authority, with special reference to the Roman Catholic Church and the churches of the Reformation. The Development of Rom Catholic Sacramental Tbeohgy The Early Church The orign of modem Roman Catholic sacramental theology developed in the earliest history of the Christian church. While the NT does not utilize the term "~acrament,~'some scholars speculate that the postapostolic church felt it necessary to bring Christianity into line with other rebons of the he,which utilized various "mysterious rites." The Greek equivalent for the term "sacrament," mu~tmbn,reinforces this view. In addition to the Lord's Supper and baptism, which had always carried special importance, the early church recognized many rites as 'holy ordinances."' It was not until the Middle Ages that the number of sacraments was officially defked.2 The term "sacrament," a translation of the Latin sacramenturn ("oath," 'G. -

The Well-Trained Theologian

THE WELL-TRAINED THEOLOGIAN essential texts for retrieving classical Christian theology part 1, patristic and medieval Matthew Barrett Credo 2020 Over the last several decades, evangelicalism’s lack of roots has become conspicuous. Many years ago, I experienced this firsthand as a university student and eventually as a seminary student. Books from the past were segregated to classes in church history, while classes on hermeneutics and biblical exegesis carried on as if no one had exegeted scripture prior to the Enlightenment. Sometimes systematics suffered from the same literary amnesia. When I first entered the PhD system, eager to continue my theological quest, I was given a long list of books to read just like every other student. Looking back, I now see what I could not see at the time: out of eight pages of bibliography, you could count on one hand the books that predated the modern era. I have taught at Christian colleges and seminaries on both sides of the Atlantic for a decade now and I can say, in all honesty, not much has changed. As students begin courses and prepare for seminars, as pastors are trained for the pulpit, they are not required to engage the wisdom of the ancient past firsthand or what many have labelled classical Christianity. Such chronological snobbery, as C. S. Lewis called it, is pervasive. The consequences of such a lopsided diet are now starting to unveil themselves. Recent controversy over the Trinity, for example, has manifested our ignorance of doctrines like eternal generation, a doctrine not only basic to biblical interpretation and Christian orthodoxy for almost two centuries, but a doctrine fundamental to the church’s Christian identity. -

THE SCHOLASTIC PERIOD Beatus Rhenanus, a Close Friend Of

CHAPTER THREE MEDIEVAL HISTORY: THE SCHOLASTIC PERIOD Beatus Rhenanus, a close friend of Erasmus and the most famous humanist historian of Germany, dated the rise of scholasticism (and hence the decay of theology) at “around the year of grace 1140”, when men like Peter Lombard (1095/1100–1160), Peter Abelard (1079–1142), and Gratian († c. 1150) were active.1 Erasmus, who cared relatively little about chronology, never gave such a precise indication, but one may assume that he did not disagree with Beatus, whose views may have directly influenced him. As we have seen, he believed that the fervour of the gospel had grown cold among most Christians during the previous four hundred years.2 Although his statement pertained to public morality rather than to theology,3 other passages from his work confirm that in Erasmus’ eyes those four centuries represented the age of scholasticism. In his biography of Jerome, he complained that for the scholastics nobody “who had lived before the last four hundred years” was a theologian,4 and in a work against Noël Bédier he pointed to a tradition of “four hun- dred years during which scholastic theology, gravely burdened by the decrees of the philosophers and the contrivances of the sophists, has wielded its reign”.5 In one other case he assigned to scholasti- cism a tradition of three centuries.6 Thus by the second half of the twelfth century, Western Christendom, in Erasmus’ conception, had entered the most distressing phase of its history, even though the 1 See John F. D’Amico, “Beatus Rhenanus, Tertullian and the Reformation: A Humanist’s Critique of Scholasticism”, Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte 71 (1980), 37–63 esp. -

LITURGY NEWSLETTER Vol

LITURGY NEWSLETTER Vol. 5 No. 1 November 2004 A Quarterly Newsletter prepared by the Liturgy Office of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales General Instruction of the Roman Missal The translation and adaptation of the revised General Instruction for the use of the Church in orty years (since England and Wales was approved by Cardinal Arinze in August. It will be published by CTS, on the publication Fof Sacrosanctum behalf of the Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales in the Season of Easter 2005. Concilium, the Constitu- The 3rd edition of the Roman Missal, was published in Latin in 2002. The General Instruction tion on the Sacred Liturgy), it is appropriate forms an integral part of the ritual book, and a translation of it would not normally be published to review the ground in advance of the whole book. However in this case the Bishops of England and Wales sought covered. the permission of the Holy See to publish a version of the General Instruction for use in their I have already suggested dioceses, because of the significance of the celebration of the Mass in the life of the Catholic on former occasions a community, and because the revised General Instruction has had force of law from the time of the sort of examination of publication of the Latin edition. conscience concern- ing the reception given ICEL continues to prepare a translation of the whole Missal for the consideration of the Bishops of to the Second Vatican the English-speaking world. Its Episcopal Board met during the summer to consider responses to the Council. -

Jeder Treu Auf Seinem Posten: German Catholics

JEDER TREU AUF SEINEM POSTEN: GERMAN CATHOLICS AND KULTURKAMPF PROTESTS by Jennifer Marie Wunn (Under the Direction of Laura Mason) ABSTRACT The Kulturkampf which erupted in the wake of Germany’s unification touched Catholics’ lives in multiple ways. Far more than just a power struggle between the Catholic Church and the new German state, the conflict became a true “struggle for culture” that reached into remote villages, affecting Catholic men, women, and children, regardless of their age, gender, or social standing, as the state arrested clerics and liberal, Protestant polemicists castigated Catholics as ignorant, anti-modern, effeminate minions of the clerical hierarchy. In response to this assault on their faith, most Catholics defended their Church and clerics; however, Catholic reactions to anti- clerical legislation were neither uniform nor clerically-controlled. Instead, Catholics’ Kulturkampf activism took many different forms, highlighting both individual Catholics’ personal agency in deciding if, when, and how to take part in the struggle as well as the diverse factors that motivated, shaped, and constrained their activism. Catholics resisted anti-clerical legislation in ways that reflected their personal lived experience; attending to the distinctions between men’s and women’s activism or those between older and younger Catholics’ participation highlights individuals’ different social and communal roles and the diverse ways in which they experienced and negotiated the dramatic transformations the new nation underwent in its first decade of existence. Investigating the patterns and distinctions in Catholics’ Kulturkampf activism illustrates how Catholics understood the Church-State conflict, making clear what various groups within the Catholic community felt was at stake in the struggle, as well as how external factors such as the hegemonic contemporary discourses surrounding gender roles, class status, age and social roles, the division of public and private, and the feminization of religion influenced their activism. -

![THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7828/the-humble-beginnings-of-the-inquirer-lifestyle-series-fitness-fashion-with-samsung-july-9-2014-fashion-show-667828.webp)

THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]

1 The Humble Beginnings of “Inquirer Lifestyle Series: Fitness and Fashion with Samsung Show” Contents Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ................................................................ 8 Vice-Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................... 9 Popes .................................................................................................................................. 9 Board Members .............................................................................................................. 15 Inquirer Fitness and Fashion Board ........................................................................... 15 July 1, 2013 - present ............................................................................................... 15 Philippine Daily Inquirer Executives .......................................................................... 16 Fitness.Fashion Show Project Directors ..................................................................... 16 Metro Manila Council................................................................................................. 16 June 30, 2010 to June 30, 2016 .............................................................................. 16 June 30, 2013 to present ........................................................................................ 17 Days to Remember (January 1, AD 1 to June 30, 2013) ........................................... 17 The Philippines under Spain ...................................................................................... -

Agrarian Metaphors 397

396 Agrarian Metaphors 397 The Bible provided homilists with a rich store of "agricultural" metaphors and symbols) The loci classici are passages like Isaiah's "Song of the Vineyard" (Is. 5:1-7), Ezekiel's allegories of the Tree (Ez. 15,17,19:10-14,31) and christ's parables of the Sower (Matt. 13: 3-23, Mark 4:3-20, Luke 8:5-15) ,2 the Good Seed (Matt. 13:24-30, Mark 4:26-29) , the Barren Fig-tree (Luke 13:6-9) , the Labourers in the Vineyard (Matt. 21:33-44, Mark 12:1-11, Luke 20:9-18), and the Mustard Seed (Matt. 13:31-32, Mark 4:30-32, Luke 13:18-19). Commonplace in Scripture, however, are comparisons of God to a gardener or farmer,5 6 of man to a plant or tree, of his soul to a garden, 7and of his works to "fruits of the spirit". 8 Man is called the "husbandry" of God (1 Cor. 3:6-9), and the final doom which awaits him is depicted as a harvest in which the wheat of the blessed will be gathered into God's storehouse and the chaff of the damned cast into eternal fire. Medieval scriptural commentaries and spiritual handbooks helped to standardize the interpretation of such figures and to impress them on the memories of preachers (and their congregations). The allegorical exposition of the res rustica presented in Rabanus Maurus' De Universo (XIX, cap.l, "De cultura agrorum") is a distillation of typical readings: Spiritaliter ... in Scripturis sacris agricultura corda credentium intelliguntur, in quibus fructus virtutuxn germinant: unde Apostolus ad credentes ait [1 Cor. -

The Christian Movement in the Second and Third Centuries

WMF1 9/13/2004 5:36 PM Page 10 The Christian Movement 1 in the Second and Third Centuries 1Christians in the Roman Empire 2 The First Theologians 3Constructing Christian Churches 1Christians in the Roman Empire We begin at the beginning of the second century, a time of great stress as Christians struggled to explain their religious beliefs to their Roman neighbors, to create liturgies that expressed their beliefs and values, and to face persecution and martyrdom cour- ageously. It may seem odd to omit discussion of the life and times of Christianity’s founder, but scholarly exploration of the first century of the common era is itself a field requiring a specific expertise. Rather than focus on Christian beginnings directly, we will refer to them as necessitated by later interpretations of scripture, liturgy, and practice. Second-century Christians were diverse, unorganized, and geographically scattered. Paul’s frequent advocacy of unity among Christian communities gives the impression of a unity that was in fact largely rhetorical. Before we examine Christian movements, however, it is important to remind ourselves that Christians largely shared the world- view and social world of their neighbors. Polarizations of “Christians” and “pagans” obscure the fact that Christians were Romans. They participated fully in Roman culture and economic life; they were susceptible, like their neighbors, to epidemic disease and the anxieties and excitements of city life. As such, they were repeatedly shocked to be singled out by the Roman state for persecution and execution on the basis of their faith. The physical world of late antiquity The Mediterranean world was a single political and cultural unit. -

Bible/Book Studies

1 BIBLE/BOOK STUDIES A Gospel for People on the Journey Luke Novalis Scripture Studies Series Each of the writers of the Gospels has his particular vision of Jesus. For Luke, Jesus is not only the one who announces the Good News of salvation: Jesus is our salvation. 9 copies Editor: Michael Trainor A Gospel for Searching People Matthew Novalis Scripture Studies Series Each of the writers of the Gospels has his particular vision of Jesus. For Matthew, Jesus is the great teacher (Matt. 23:8). But teacher and teachings are inextricable bound together, Matthew tells us. Jesus stands alone as unique teacher because of his special relationship with God: he alone is Son of man and Son of God. And Jesus still teaches those who are searching for meaning and purpose in life today. 9 copies Editor: Michael Trainor A Gospel for Struggling People Mark Novalis Scripture Studies Series “Who do you say that I am? In Mark’s Gospel, no one knows who Jesus is until, in Chapter 8, Peter answers: “You are the Christ.” But what does this mean? The rest of the Gospel shows what kind of Christ or Messiah Jesus is: he has come to suffer and die for his people. Teaching on discipleship and predictions of his death point ahead to the focus of the Gospel-the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus. 9 copies Editor: Michael Trainor Beautiful Bible Stories Beautiful Bible Stories by Rev. Charles P. Roney, D.D. and Rev. Wilfred G. Rice, Collaborator Designed to stimulate a greater interest in the Bible through the arrangement of extensive References, Suggestions for Study, and Test Questions. -

Companions on the Journey

The Catholic Women’s League of Canada 1990-2005 companions on the journey Sheila Ross The Catholic Women’s League of Canada C-702 Scotland Avenue Winnipeg, MB R3M 1X5 Tel: (888) 656-4040 Fax: (888) 831-9507 Website: www.cwl.ca E-mail: [email protected] The Catholic Women’s League of Canada 1990-2005: companions on the journey Contents Introduction ................................................................................................. 2 1990: Woman: Sharing in the Life and Mission of the Church.................. 8 1991: Parish: A Family of the Local Church: Part 1 ................................. 16 1992: Parish: A Family of the Local Church: Part II ................................. 23 1993: The Catholic Women’s League of Canada – rooted in gospel values: Part I........................................................................................ 30 1994: The Catholic Women’s League of Canada – rooted in gospel values: Part II ....................................................................................... 36 1995: The Catholic Women’s League of Canada − calling its members to holiness............................................................................................ 42 1996: The Catholic Women’s League of Canada − through service to the people of God: Part I ................................................................... 47 1997: The Catholic Women’s League of Canada − through service to the people of God: Part II .................................................................. 54 1998: People of God -

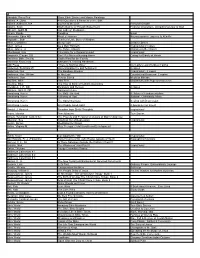

St. Barbara's Lending Library 2016.Xlsx

A Abradale Press Pub. Great Bible Stories and Master Paintings Adams, A. Dana 4000 Questions & Answers on the Bible Adams ,Kathleen, MA Journal to the Self Personal Growth Adams, Scott God's Debris: A Thought Experiment Fictional Characters, Untraditional view of God Albright, Judith M, Our Lady of Medjugorje Alcorn, Randy Deadline Novel Alexander, Eben MD Proof of Heaven Neurosurgeon's Journey to Afterlife Algozzine, Bob Teacher's Little Book of Wisdom Allen, Constance Sleep Tight Sesame Street Allen, James As a Man Thinketh Inspirational 2 copies Allen, John L. Jr The Future Church Changes in the Church Allenbaugh, Kay Chocolate for a Woman's Heart Inspirational Amarnick, Claude, DO Don't Put Me in a Nursing Home Caring for Elderly at Home American Bible Society God's Word for the Family American Red Cross Babysitter's Training Handbook AMI Press "There Is Nothing More" Our Lady's Last Words at Fatima Anderson, Bernhard W. Understanding the Old Testament 2 copies Anderson, Neil The Bondage Breaker Inspirational - 2 copies Anderson, Rev. William In His Light Catechetical Resource 2 copies Andriacco, Dan Screen Saved Media in Ministry Aquilina, Mike Take Five Meditations with Pope Benedict XVI Aquilina, Mike The How to Book of Catholic Devotions Arendzen, J. P., DD Purgatory and Heaven 2 copies Arintero, John G, OP Holiness Is Love Armstrong, Karen The Battle for God A History of Fundamentalism Armstrong, Karen A History of God Judaism, Christianity, Islam Armstrong, Karen The Spiral Staircase Dealing with Depression Armstrong, Louise Kiss Daddy Good-night A Speak-out on Incest Arnold, J.