MYANMAR National Strategy and Action Plan (NSAP)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2D Seismic Survey in Block AD- 10, Offshore Myanmar

2D Seismic Survey in Block AD- 10, Offshore Myanmar Initial Environmental Examination 02 December 2015 Environmental Resources Management www.erm.com The world’s leading sustainability consultancy 2D Seismic Survey in Block AD-10, Environmental Resources Management Offshore Myanmar ERM-Hong Kong, Limited 16/F, Berkshire House 25 Westlands Road Initial Environmental Examination Quarry Bay Hong Kong Telephone: (852) 2271 3000 Facsimile: (852) 2723 5660 Document Code: 0267094_IEE_Cover_AD10_EN.docx http://www.erm.com Client: Project No: Statoil Myanmar Private Limited 0267094 Summary: Date: 02 December 2015 Approved by: This document presents the Initial Environmental Examination (IEE) for 2D Seismic Survey in Block AD-10, as required under current Draft Environmental Impact Assessment Procedures Craig A. Reid Partner 1 Addressing MOECAF Comments, Final for MOGE RS CAR CAR 02/12/2015 0 Draft Final RS JNG CAR 31/08/2015 Revision Description By Checked Approved Date Distribution Internal Public Confidential CONTENTS 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1-1 1.1 PURPOSE AND EXTENT OF THE IEE REPORT 1-1 1.2 SUMMARY OF THE ACTIVITIES UNDERTAKEN DURING THE IEE STUDY 1-2 1.3 PROJECT ALTERNATIVES 1-2 1.4 DESCRIPTION OF THE ENVIRONMENT TO BE AFFECTED BY THE PROJECT 1-4 1.5 SIGNIFICANT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS 1-5 1.6 THE PUBLIC CONSULTATION AND PARTICIPATION PROCESS 1-6 1.7 SUMMARY OF THE EMP 1-7 1.8 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE IEE REPORT 1-8 2 INTRODUCTION 2-1 2.1 PROJECT OVERVIEW 2-1 2.2 PROJECT PROPONENT 2-1 2.3 THIS INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL EVALUATION (IEE) -

National Report of Myanmar

1 NATIONAL REPORT OF MYANMAR On the Sustainable Management of The Bay of Bengal Large Marine Ecosystem (BOBLME) GCP/RAS/179/WBG Department of Fisheries Fishing Grounds of Myanmar and Landing Sites 92 30’ 93 30’ 94 30’ 95 30’ 96 30’ 97 30’ 98 30’ 99 a 1 SITTWAY T O EN F F A1 A2 M IS T H R 20 E 20 A R P I E E A3 A4 b A5 A6 S D 30’ 30’ c A10 A7 A8 A9 19 19 d A14 THANDWE A11 A12 A13 A15 30’ HANDWETHANDWE 30’ e A16 A17 A18 A19 A20 A 18 2 18 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 GWA 30’ f 30’ B6 B7 B8 B9 B10 17 g 17 YANGON B11 B12 B13 B14 B15 PATHEIN 30’ h 30’ i B20 B16 B17 B18 B19 D2 D3 B j D1 3 16 16 4 C3 C1 C2 k C4 C5 D4 D5 D6 D7 D8 30’ BAS 30’ E L I NE YE C6 C7 C8 C9 C10 D9 D10 D11 D12 D13 TER RITO 15 15 RIA L LI NE YE C11 C12 C13 C14 C15 D14 D15 D16 D17 D18 30’ 30’ l C16 C17 C18 C19 C20 D19 D20 D21 D22 D23 DAWEI 14 C m 14 5 C21 C22 C23 C24 8 9 6 C25 D24 D25 D26 D27 D28 D D 29 30’ 7 10 30’ E1 E2 E3 E4 E5 E6 13 13 11 E8 E9 E10 n E11 E12 E7 30’ 30’ o MYEIK 12 MYEIK E13 E14 E15 E16 E17 E18 12 p 12 q 13 E20 E21 E22 E23 E24 E25 E 30’ 14 30’ F F2 F5 F7 1 F3 F4 F6 11 11 15 F F9 F10 F11 F12 F13 F14 r 30’ 8 30’ s 16 F 15 17 F16 F17 F18 F19 F20 F21 F 10 18 10 t KAWTHOUNG u v 92 30’ 93 30’ 94 30’ 95 30’ 96 30’ 97 30’ 98 30’ 99 Prepared by Myint Pe (National Consultant) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. -

Socio-Economics of Mangrove Ecosystem in South-Eastern Ayeyarwady Delta Area of Myanmar ©2019 Myint 227

Journal of Aquaculture & Marine Biology Research Article Open Access Socio-economics of mangrove ecosystem in South- eastern Ayeyarwady Delta area of Myanmar Abstract Volume 8 Issue 6 - 2019 Coastal communities are dependent on the resources available in mangrove ecosystems. Kyi Kyi Myint The loss of these ecosystems would mean local, national and global welfare losses. Healthy Department of Botany, University of Magway, Myanmar mangrove ecosystems were related with integrated ecological and economical processes by local people. In the present study, uses of mangroves, products and the fishery status of Correspondence: Kyi Kyi Myint, Associate Professor, local areas have been studied. The mangrove forests from the study areas provide charcoal, Department of Botany, Magway University, Myanmar, firewood, food and some medicinal plants for local people. To assess the economic value of Email the regions, the local people from three villages who lived in and near the mangrove forest were questioned and documented. The households studied were categorized into three Received: November 14, 2019 | Published: December 03, groups such as poor, middle and rich class and then their monthly income and kinds of jobs 2019 studied. The products and works based on mangrove forest and water ways of study areas were the production of Nipa thatches, dried fishes, dried shrimp, nga-pi, pickled shrimp, shrimp sauce and charcoals. Keywords: Ayeyarwady delta, Nipa thatches, nga-pi, pickled shrimp Introduction the two conflicting demands on mangrove lands. Apportioning of the mangrove land resource to these two major uses under the concept Mangrove forests were crucial of significance for local people, of sustainable management of the ecosystem needs further research providing food, shelter and, medicinal and other uses. -

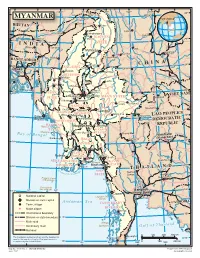

Map of Myanmar

94 96 98 J 100 102 ° ° Indian ° i ° ° 28 n ° Line s Xichang Chinese h a MYANMAR Line J MYANMAR i a n Tinsukia g BHUTAN Putao Lijiang aputra Jorhat Shingbwiyang M hm e ra k Dukou B KACHIN o Guwahati Makaw n 26 26 g ° ° INDIA STATE n Shillong Lumding i w d Dali in Myitkyina h Kunming C Baoshan BANGLADE Imphal Hopin Tengchong SH INA Bhamo C H 24° 24° SAGAING Dhaka Katha Lincang Mawlaik L Namhkam a n DIVISION c Y a uan Gejiu Kalemya n (R Falam g ed I ) Barisal r ( r Lashio M a S e w k a o a Hakha l n Shwebo w d g d e ) Chittagong y e n 22° 22° CHIN Monywa Maymyo Jinghong Sagaing Mandalay VIET NAM STATE SHAN STATE Pongsali Pakokku Myingyan Ta-kaw- Kengtung MANDALAY Muang Xai Chauk Meiktila MAGWAY Taunggyi DIVISION Möng-Pan PEOPLE'S Minbu Magway Houayxay LAO 20° 20° Sittwe (Akyab) Taungdwingyi DEMOCRATIC DIVISION y d EPUBLIC RAKHINE d R Ramree I. a Naypyitaw Loikaw w a KAYAH STATE r r Cheduba I. I Prome (Pye) STATE e Bay Chiang Mai M kong of Bengal Vientiane Sandoway (Viangchan) BAGO Lampang 18 18° ° DIVISION M a e Henzada N Bago a m YANGON P i f n n o aThaton Pathein g DIVISION f b l a u t Pa-an r G a A M Khon Kaen YEYARWARDY YangonBilugyin I. KAYIN ATE 16 16 DIVISION Mawlamyine ST ° ° Pyapon Amherst AND M THAIL o ut dy MON hs o wad Nakhon f the Irra STATE Sawan Nakhon Preparis Island Ratchasima (MYANMAR) Ye Coco Islands 92 (MYANMAR) 94 Bangkok 14° 14° ° ° Dawei (Krung Thep) National capital Launglon Bok Islands Division or state capital Andaman Sea CAMBODIA Town, village TANINTHARYI Major airport DIVISION Mergui International boundary 12° Division or state boundary 12° Main road Mergui n d Secondary road Archipelago G u l f o f T h a i l a Railroad 0 100 200 300 km Chumphon The boundaries and names shown and the designations Kawthuang 10 used on this map do not imply official endorsement or ° acceptance by the United Nations. -

Threatened Jott

Journal ofThreatened JoTT TaxaBuilding evidence for conservation globally PLATINUM OPEN ACCESS 10.11609/jott.2020.12.3.15279-15406 www.threatenedtaxa.org 26 February 2020 (Online & Print) Vol. 12 | No. 3 | Pages: 15279–15406 ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) ISSN 0974-7907 (Online); ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Publisher Host Wildlife Information Liaison Development Society Zoo Outreach Organization www.wild.zooreach.org www.zooreach.org No. 12, Thiruvannamalai Nagar, Saravanampatti - Kalapatti Road, Saravanampatti, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641035, India Ph: +91 9385339863 | www.threatenedtaxa.org Email: [email protected] EDITORS English Editors Mrs. Mira Bhojwani, Pune, India Founder & Chief Editor Dr. Fred Pluthero, Toronto, Canada Dr. Sanjay Molur Mr. P. Ilangovan, Chennai, India Wildlife Information Liaison Development (WILD) Society & Zoo Outreach Organization (ZOO), 12 Thiruvannamalai Nagar, Saravanampatti, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641035, Web Design India Mrs. Latha G. Ravikumar, ZOO/WILD, Coimbatore, India Deputy Chief Editor Typesetting Dr. Neelesh Dahanukar Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER), Pune, Maharashtra, India Mr. Arul Jagadish, ZOO, Coimbatore, India Mrs. Radhika, ZOO, Coimbatore, India Managing Editor Mrs. Geetha, ZOO, Coimbatore India Mr. B. Ravichandran, WILD/ZOO, Coimbatore, India Mr. Ravindran, ZOO, Coimbatore India Associate Editors Fundraising/Communications Dr. B.A. Daniel, ZOO/WILD, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641035, India Mrs. Payal B. Molur, Coimbatore, India Dr. Mandar Paingankar, Department of Zoology, Government Science College Gadchiroli, Chamorshi Road, Gadchiroli, Maharashtra 442605, India Dr. Ulrike Streicher, Wildlife Veterinarian, Eugene, Oregon, USA Editors/Reviewers Ms. Priyanka Iyer, ZOO/WILD, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641035, India Subject Editors 2016–2018 Fungi Editorial Board Ms. Sally Walker Dr. B. -

Diversidad Genética En Especies Del Género Phoenix L

Universidad Miguel Hernández de Elche (España) Doctorado en Recursos y Tecnologías Agroalimentarias DIVERSIDAD GENÉTICA EN ESPECIES DEL GÉNERO PHOENIX L. TESIS DOCTORAL ENCARNACIÓN CARREÑO SÁNCHEZ ORIHUELA (ESPAÑA) 2017 Diversidad genética en especies del género Phoenix L. Tesis Doctoral realizada por Encarnación Carreño Sánchez, Licenciada en Ciencias Biológicas en la Universidad de Murcia y Máster Universitario en Agroecología, Desarrollo Rural y Agroturismo en la Universidad Miguel Hernández de Elche (Alicante), para la obtención del grado de Doctor. Fdo.: Encarnación Carreño Sánchez Orihuela, 15 de junio de 2017 Dr. José Ramón Díaz Sánchez, Dr. Ingeniero Agrónomo, Catedrático de Universidad y Director del Departamento de Tecnología Agroalimentaria de la Universidad Miguel Hernández, INFORMA: Que atendiendo al informe presentado por los Dres. Concepción Obón de Castro profesora Titular del Departamento de Biología Aplicada de la Universidad Miguel Hernández de Elche, Diego Rivera Núñez Catedrático de Universidad del Departamento de Biología Vegetal de la Universidad de Murcia, y Francisco Alcaraz Ariza Catedrático de Universidad del Departamento de Biología Vegetal de la Universidad de Murcia, la Tesis Doctoral titulada “Diversidad genética en especies del género Phoenix” de la que es autora la licenciada en Biología y Master en Agroecología Desarrollo Rural y Agroturismo Dña. Encarnación Carreño Sánchez ha sido realizada bajo la dirección de los Doctores citados, puede ser presentada para su correspondiente exposición pública. Y para que conste a los efectos oportunos firmo el presente informe en Orihuela a _______de ________ de 2017. Fdo.: Dr. José Ramón Díaz Sánchez Dr. Concepción Obón de Castro, Profesora Titular del Departamento de Biología Aplicada de la Universidad Miguel Hernández de Elche, CERTIFICA: Que la Tesis Doctoral titulada “Diversidad genética en especies del género Phoenix” de la que es autor la licenciada en Biología y Master en Agroecología Desarrollo Rural y Agroturismo Da. -

Biosíntesi, Distribució, Acumulació I Funció De La Vitamina E En Llavors: Mecanismes De Control

Biosíntesi, distribució, acumulació i funció de la vitamina E en llavors: mecanismes de control Laura Siles Suárez Aquesta tesi doctoral està subjecta a la llicència Reconeixement- NoComercial – SenseObraDerivada 3.0. Espanya de Creative Commons. Esta tesis doctoral está sujeta a la licencia Reconocimiento - NoComercial – SinObraDerivada 3.0. España de Creative Commons. This doctoral thesis is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0. Spain License. Barcelona, febrer de 2017 Biosíntesi, distribució, acumulació i funció de la vitamina E en llavors: mecanismes de control Memòria presentada per Laura Siles Suarez per a optar al grau de Doctora per la Universitat de Barcelona. Aquest treball s’emmarca dins el programa de doctorat de BIOLOGIA VEGETAL del Departament de Biologia Evolutiva, Ecologia i Ciències Ambientals (BEECA) de la Facultat de Biologia de la Universitat de Barcelona. El present treball ha estat realitzat al Departament de Biologia Evolutiva, Ecologia i Ciències Ambientals de la Facultat de Biologia (BEECA) de la Universitat de Barcelona sota la direcció de la Dra. Leonor Alegre Batlle i el Dr. Sergi Munné Bosch. Doctoranda: Directora i Codirector de Tesi: Tutora de Tesi: Laura Siles Suarez Dra. Leonor Alegre Batlle Dra. Leonor Alegre Batlle Dr. Sergi Munné Bosch “Mira profundamente en la naturaleza y entonces comprenderás todo mejor”- Albert Einstein. “La creación de mil bosques está en una bellota”-Ralph Waldo Emerson. A mi familia, por apoyarme siempre, y a mis bichejos peludos Índex ÍNDEX AGRAÏMENTS i ABREVIATURES v INTRODUCCIÓ GENERAL 1 Vitamina E 3 1.1.Descobriment i estudi 3 1.2.Estructura química i classes 3 Distribució de la vitamina E 5 Biosíntesi de vitamina E 6 3.1. -

Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Dark Septate Fungi in Plants Associated with Aquatic Environments Doi: 10.1590/0102-33062016Abb0296

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and dark septate fungi in plants associated with aquatic environments doi: 10.1590/0102-33062016abb0296 Table S1. Presence of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) and/or dark septate fungi (DSF) in non-flowering plants and angiosperms, according to data from 62 papers. A: arbuscule; V: vesicle; H: intraradical hyphae; % COL: percentage of colonization. MYCORRHIZAL SPECIES AMF STRUCTURES % AMF COL AMF REFERENCES DSF DSF REFERENCES LYCOPODIOPHYTA1 Isoetales Isoetaceae Isoetes coromandelina L. A, V, H 43 38; 39 Isoetes echinospora Durieu A, V, H 1.9-14.5 50 + 50 Isoetes kirkii A. Braun not informed not informed 13 Isoetes lacustris L.* A, V, H 25-50 50; 61 + 50 Lycopodiales Lycopodiaceae Lycopodiella inundata (L.) Holub A, V 0-18 22 + 22 MONILOPHYTA2 Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum arvense L. A, V 2-28 15; 19; 52; 60 + 60 Osmundales Osmundaceae Osmunda cinnamomea L. A, V 10 14 Salviniales Marsileaceae Marsilea quadrifolia L.* V, H not informed 19;38 Salviniaceae Azolla pinnata R. Br.* not informed not informed 19 Salvinia cucullata Roxb* not informed 21 4; 19 Salvinia natans Pursh V, H not informed 38 Polipodiales Dryopteridaceae Polystichum lepidocaulon (Hook.) J. Sm. A, V not informed 30 Davalliaceae Davallia mariesii T. Moore ex Baker A not informed 30 Onocleaceae Matteuccia struthiopteris (L.) Tod. A not informed 30 Onoclea sensibilis L. A, V 10-70 14; 60 + 60 Pteridaceae Acrostichum aureum L. A, V, H 27-69 42; 55 Adiantum pedatum L. A not informed 30 Aleuritopteris argentea (S. G. Gmel) Fée A, V not informed 30 Pteris cretica L. A not informed 30 Pteris multifida Poir. -

Fossil Palm Beetles Refine Upland Winter Temperatures in the Early Eocene Climatic Optimum

Fossil palm beetles refine upland winter temperatures in the Early Eocene Climatic Optimum S. Bruce Archibalda,b,c,1, Geoffrey E. Morsed, David R. Greenwoode,f, and Rolf W. Mathewesa aDepartment of Biological Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada V5A 1S6; bRoyal British Columbia Museum, Victoria, BC, Canada V8W 1A1; cEntomology Department, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Cambridge, MA 02138; dBiology Department, University of San Diego, San Diego, CA 92110; eBiology Department, Brandon University, Brandon, MB, Canada R7A 6A9; and fBarbara Hardy Institute, University of South Australia, Adelaide, SA 5000, Australia Edited by Thure E. Cerling, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, and approved April 11, 2014 (received for review December 16, 2013) Eocene climate and associated biotic patterns provide an analog e.g., the current dramatic mountain pine beetle infestations of system to understand their modern interactions. The relationship western North America (7, 8). between mean annual temperatures and winter temperatures— temperature seasonality—may be an important factor in this dy- Palms as Indicators of Winter Temperatures namic. Fossils of frost-intolerant palms imply low Eocene temper- Eocene temperature seasonality has been characterized using ature seasonality into high latitudes, constraining average winter proxy thermometers such as palms (Arecaceae), whose seeds and temperatures there to >8 °C. However, their presence in a paleo- seedlings cannot survive sustained freezing, today limiting their community may be obscured by taphonomic and identification natural distribution to regions of CMMT >5 °C (3, 9), although factors for macrofossils and pollen. We circumvented these prob- some palms may tolerate CMMT ∼2.5 °C (Fig. 1). -

Mar2009sale Finalfinal.Pub

March SFPS Board of Directors 2009 2009 The Palm Report www.southfloridapalmsociety.com Tim McKernan President John Demott Vice President Featured Palm George Alvarez Treasurer Bill Olson Recording Secretary Lou Sguros Corresponding Secretary Jeff Chait Director Sandra Farwell Director Tim Blake Director Linda Talbott Director Claude Roatta Director Leonard Goldstein Director Jody Haynes Director Licuala ramsayi Palm and Cycad Sale The Palm Report - March 2009 March 14th & 15th This publication is produced by the South Florida Palm Society as Montgomery Botanical Center a service to it’s members. The statements and opinions expressed 12205 Old Cutler Road, Coral Gables, FL herein do not necessarily represent the views of the SFPS, it’s Free rare palm seedlings while supplies last Board of Directors or its editors. Likewise, the appearance of ad- vertisers does not constitute an endorsement of the products or Please visit us at... featured services. www.southfloridapalmsociety.com South Florida Palm Society Palm Florida South In This Issue Featured Palm Ask the Grower ………… 4 Licuala ramsayi Request for E-mail Addresses ………… 5 This large and beautiful Licuala will grow 45-50’ tall in habitat and makes its Membership Renewal ………… 6 home along the riverbanks and in the swamps of the rainforest of north Queen- sland, Australia. The slow-growing, water-loving Licuala ramsayi prefers heavy Featured Palm ………… 7 shade as a juvenile but will tolerate several hours of direct sun as it matures. It prefers a slightly acidic soil and will appreciate regular mulching and protection Upcoming Events ………… 8 from heavy winds. While being one of the more cold-tolerant licualas, it is still subtropical and should be protected from frost. -

Striatiguttulaceae, a New Pleosporalean Family to Accommodate Longicorpus and Striatiguttula Gen

A peer-reviewed open-access journal MycoKeys 49:Striatiguttulaceae 99–129 (2019) , a new pleosporalean family to accommodate Longicorpus and... 99 doi: 10.3897/mycokeys.49.30886 RESEARCH ARTICLE MycoKeys http://mycokeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Striatiguttulaceae, a new pleosporalean family to accommodate Longicorpus and Striatiguttula gen. nov. from palms Sheng-Nan Zhang1,2,3,4, Kevin D. Hyde4, E.B. Gareth Jones5, Rajesh Jeewon6, Ratchadawan Cheewangkoon3, Jian-Kui Liu1,2 1 Center for Bioinformatics, School of Life Science and Technology, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu 611731, P.R. China 2 Guizhou Key Laboratory of Agricultural Biotechnology, Guizhou Academy of Agricultural Science, Guiyang 550006, P.R. China 3 Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, Faculty of Agriculture, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand4 Center of Excellence in Fungal Research, Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai 57100, Thailand5 Nantgaredig 33B St. Edwards Road, Southsea, Hants, UK 6 Department of Health Sciences, Faculty of Science, University of Mauritius, Reduit, Mauritius, 80837, Mauritius Corresponding author: Jian-Kui Liu ([email protected]) Academic editor: G. Mugambi | Received 28 October 2018 | Accepted 29 January 2019 | Published 1 April 2019 Citation: Zhang S-N, Hyde KD, Jones EBG, Jeewon R, Cheewangkoon R, Liu J-K (2019) Striatiguttulaceae, a new pleosporalean family to accommodate Longicorpus and Striatiguttula gen. nov. from palms. MycoKeys 49: 99–129. https://doi.org/10.3897/mycokeys.49.30886 Abstract Palms represent the most morphological diverse monocotyledonous plants and support a vast array of fungi. Recent examinations of palmicolous fungi in Thailand led to the discovery of a group of morpho- logically similar and interesting taxa. -

Palms, Cycads & Pandans

Mangrove Guidebook for Southeast Asia Part 2: DESCRIPTIONS – Palms, cycads & pandans GROUP F: PALMS, CYCADS & PANDANS 491 Mangrove Guidebook for Southeast Asia Part 2: DESCRIPTIONS – Palms, cycads & pandans Fig. 131. Calamus erinaceus (Becc.) Dransfield. (a) Leaf axis, with two leaflets still attached, (b) whip-like, hooked leaf-tip, (c) female inflorescence, (d) male inflorescence, and (e) base of leaf (leaf sheath) , showing insertion of spines. 492 Mangrove Guidebook for Southeast Asia Part 2: DESCRIPTIONS – Palms, cycads & pandans ARECACEAE 131 Calamus erinaceus (Becc.) Dransfield Synonyms : Calamus aquatilis, Daemonorops erinaceus, Daemonorops leptopus Vernacular name(s) : Rotan Bakau (Mal., Ind.) Description : A robust, multiple-stemmed climbing palm (rattan) with whip-like hooks at the tips of its leaves. The stems climb up to 15-30m (or more), are 2-3.5 cm in diameter, but may be up to 6 cm wide if the enclosing sheaths are included. The sheaths are orange to yellowish-green, and are very densely armed with horizontal or slanted greyish- brown spines that are 2-35 mm long. The spines and the sheath epidermis are densely covered with fine grey scales. The 5-9 spines around the mouth of the leaf sheath point upward and are up to 6 cm long. The leaves are about 4.5 m long with numerous greyish-green leaflets that measure 2 by 40 cm; the leaf stalk is 20 cm. These are very regular, closely grouped, and hang laxly. They are armed with short bristles along the margins and on the veins on the underside of the leaflet. The lower surface also has minute brown scales and a thin layer of pale wax.