Price Discovery and Integration in U.S. Pecan Markets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

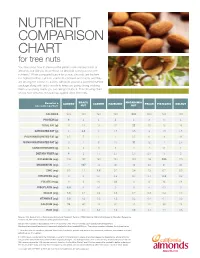

Nutrient Comparison Chart

NUTRIENT COMPARISON CHART for tree nuts You may know how to measure the perfect one-ounce portion of almonds, but did you know those 23 almonds come packed with nutrients? When compared ounce for ounce, almonds are the tree nut highest in fiber, calcium, vitamin E, riboflavin and niacin, and they are among the lowest in calories. Almonds provide a powerful nutrient package along with tasty crunch to keep you going strong, making them a satisfying snack you can feel good about. The following chart shows how almonds measure up against other tree nuts. BRAZIL MACADAMIA Based on a ALMOND CASHEW HAZELNUT PECAN PISTACHIO WALNUT one-ounce portion1 NUT NUT CALORIES 1602 190 160 180 200 200 160 190 PROTEIN (g) 6 4 4 4 2 3 6 4 TOTAL FAT (g) 14 19 13 17 22 20 13 19 SATURATED FAT (g) 1 4.5 3 1.5 3.5 2 1.5 1.5 POLYUNSATURATED FAT (g) 3.5 7 2 2 0.5 6 4 13 MONOUNSATURATED FAT (g) 9 7 8 13 17 12 7 2.5 CARBOHYDRATES (g) 6 3 9 5 4 4 8 4 DIETARY FIBER (g) 4 2 1.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 3 2 POTASSIUM (mg) 208 187 160 193 103 116 285 125 MAGNESIUM (mg) 77 107 74 46 33 34 31 45 ZINC (mg) 0.9 1.2 1.6 0.7 0.4 1.3 0.7 0.9 VITAMIN B6 (mg) 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.2 FOLATE (mcg) 12 6 20 32 3 6 14 28 RIBOFLAVIN (mg) 0.3 0 0.1 0 0 0 0.1 0 NIACIN (mg) 1.0 0.1 0.4 0.5 0.7 0.3 0.4 0.3 VITAMIN E (mg) 7.3 1.6 0.3 4.3 0.2 0.4 0.7 0.2 CALCIUM (mg) 76 45 13 32 20 20 30 28 IRON (mg) 1.1 0.7 1.7 1.3 0.8 0.7 1.1 0.8 Source: U.S. -

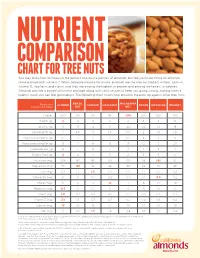

Chart for Tree Nuts

NUTRIENT COMPARISON CHART FOR TREE NUTS You may know how to measure the perfect one-ounce portion of almonds, but did you know those 23 almonds come packed with nutrients? When compared ounce for ounce, almonds are the tree nut highest in fiber, calcium, vitamin E, riboflavin and niacin, and they are among the highest in protein and among the lowest in calories. Almonds provide a powerful nutrient package along with tasty crunch to keep you going strong, making them a healthy snack you can feel good about. The following chart shows how almonds measure up against other tree nuts. BRAZIL MACADAMIA Based on a ALMOND CASHEW HAZELNUT PECAN PISTACHIO WALNUT one-ounce portion1 NUT NUT Calories 1602 190 160 180 200 200 160 190 Protein (g) 6 4 4 4 2 3 6 4 Total Fat (g) 14 19 13 17 22 20 13 18 Saturated Fat (g) 1 4.5 3 1.5 3.5 2 1.5 1.5 Polyunsaturated Fat (g) 3.5 7 2 2 0.5 6 4 13 Monounsaturated Fat (g) 9 7 8 13 17 12 7 2.5 Carbohydrates (g) 6 3 9 5 4 4 8 4 Dietary Fiber (g) 4 2 1 3 2 3 3 2 Potassium (mg) 208 187 160 193 103 116 285 125 Magnesium (mg) 77 107 74 46 33 34 31 45 Zinc (mg) 0.9 1.2 1.6 0.7 0.4 1.3 0.7 0.9 Vitamin B6 (mg) 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.2 Folate (mcg) 12 6 20 32 3 6 14 28 Riboflavin (mg) 0.3 0 0.1 0 0 0 0.1 0 Niacin (mg) 1.0 0.1 0.4 0.5 0.7 0.3 0.4 0.3 Vitamin E (mg) 7.3 1.6 0.3 4.3 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.2 Calcium (mg) 76 45 13 32 20 20 30 28 Iron (mg) 1.1 0.7 1.7 1.3 0.8 0.7 1.1 0.8 Source: U.S. -

American Pecan

THE AMERICAN PECAN CRACKING OPEN THE NUTRITION STORY OF OUR NATIVE NUT Scientific evidence suggests but does not prove YOU THINK OF THEM FOR PIE. that eating 1.5 ounces per day of most nuts, YOU ADORE THEM IN PRALINES. such as pecans, as part of a diet low in saturated BUT DID YOU KNOW PECANS fat and cholesterol may reduce the risk of ARE ACTUALLY A NUTRITION heart disease.* POWERHOUSE? U.S. Food and Drug Administration Don’t be fooled by their rich, buttery texture and naturally sweet taste, pecans are extremely *One serving of pecans (28g) contains 18g of unsaturated fat and only 2g of saturated fat. nutrient dense. The macronutrient profile of pecans is appealing to many people: Pecans contain the same beneficial unsaturated protein (3 grams), carbohydrate (4 grams) and fat (20 grams). fats that are found in other nuts, and nearly two decades of research suggests that nuts, including A handful of pecans – about 19 halves – is a good source of fiber, pecans, may help promote heart health. thiamin, and zinc, and an excellent source of copper and manganese – a mineral that’s essential for metabolism and In each 1-ounce serving of raw pecans you’ll get bone health. 12 grams of “good” monounsaturated fat, with zero cholesterol or sodium.1 Compared to other To top it off, pecans contain polyphenols, specifically flavonoids nuts, pecans are among the lowest in carbs and – which are the types of bioactive compounds found in brightly highest in fiber. colored produce.2 So think of pecans as a supernut. -

Juglans Nigra Juglandaceae L

Juglans nigra L. Juglandaceae LOCAL NAMES English (walnut,American walnut,eastern black walnut,black walnut); French (noyer noir); German (schwarze Walnuß); Portuguese (nogueira- preta); Spanish (nogal negro,nogal Americano) BOTANIC DESCRIPTION Black walnut is a deciduous tree that grows to a height of 46 m but ordinarily grows to around 25 m and up to 102 cm dbh. Black walnut develops a long, smooth trunk and a small rounded crown. In the open, the trunk forks low with a few ascending and spreading coarse branches. (Robert H. Mohlenbrock. USDA NRCS. The root system usually consists of a deep taproot and several wide- 1995. Northeast wetland flora: Field office spreading lateral roots. guide to plant species) Leaves alternate, pinnately compound, 30-70 cm long, up to 23 leaflets, leaflets are up to 13 cm long, serrated, dark green with a yellow fall colour in autumn and emits a pleasant sweet though resinous smell when crushed or bruised. Flowers monoecious, male flowers catkins, small scaley, cone-like buds; female flowers up to 8-flowered spikes. Fruit a drupe-like nut surrounded by a fleshy, indehiscent exocarp. The nut has a rough, furrowed, hard shell that protects the edible seed. Fruits Bark (Robert H. Mohlenbrock. USDA NRCS. 1995. Northeast wetland flora: Field office produced in clusters of 2-3 and borne on the terminals of the current guide to plant species) season's growth. The seed is sweet, oily and high in protein. The bitter tasting bark on young trees is dark and scaly becoming darker with rounded intersecting ridges on maturity. BIOLOGY Flowers begin to appear mid-April in the south and progressively later until early June in the northern part of the natural range. -

Pecan Halves & Pieces

Fort Bend 4-H Pecan Sale 1402 Band Rd . Suite 100 Rosenberg,TX 77471 281-342-3034 PECAN HALVES & PIECES I lb. Bag Pecan Halves—$10.00 I lb. Bag Pecan Pieces—$9.00 3 lb. Box Pecan Halves—$29.00 3 lb. Box Pecan Pieces—$28.00 FLAVORED PECANS & GIFT BASKETS 1 lb. TX Basket Mixed Choc. Pecans 12 oz Praline Frosted Pecans $20.00 $8.00 12 oz Milk Choc. Pecans $7.00 1 lb. Pecan Sampler $14.00 SPECIALTY NUTS 1 lb. Bag Hot & Spicy Peanuts 1 lb. Bag Walnut Halves 12 oz Bag Chocolate Peanuts $4.00 $9.00 $5.00 1 lb. Bag R/S Redskin Peanuts $4.00 MIXES 1 lb. Bag Cran-Slam Mix 1 lb. Bag Fiesta Mix 1 lb. Bag Hunter’s Mix $7.00 $4.00 $6.00 Dried cranberries, walnut pieces, Bbq corn sticks, taco sesame Cashews, cocktail peanuts, roasted and salted almonds, sticks, nacho cheese pea- sesame sticks, sesame roasted and salted sunflower nuts, hot & spicy peanuts seeds, natural almonds, fan- seeds, diced pineapple, black rai- cy pecan halves, peanut oil, sins, roasted and salted pumpkin salt seeds 1 lb. Bag Mountain Mix 1 lb. Texas Deluxe Mix 1 lb. Trash Mix $6.00 $9.00 $4.00 Roasted and salted cocktail Pecan halves, cashews, nat. Cocktail peanuts, hot & spicy pea- peanuts, roasted and salted Almonds, brazil nuts, pea- nuts, pretzels, sesame sticks almonds, roasted and salted nut oil, salt. cashews, raisins, and m&m's WE delicious reach _______________________________________, Would ________________________________________. Turn 15. 14. 13. 12. 11. -

Pecan Varieties for Georgia Orchards

Pecan Varieties for Georgia Orchards By Lenny Wells and Patrick Conner, Department of Horticulture stablishing a new orchard or renovating an older to consider when selecting a variety are pollination Eorchard is an exciting time for a pecan grower type, disease resistance, alternate bearing potential, because it provides an opportunity to significantly precocity (the bearing age of the tree), harvest date, improve the productivity of the farm. However, pollination type, nut size and nut quality. choosing which cultivars to plant can be one of the most difficult decisions a grower has to make. Pecan Cultivar Characteristics cultivars vary widely in yield potential, nut quality, Pollination Type date of maturity, tree form and resistance to insects Pecan trees produce separate male (catkins) and and diseases. Problems encountered due to a poor female (nut cluster) flowers on the same tree. Basic choice in cultivars can be difficult or impossible to flowering timing follows one of two patterns. Type I correct through cultural methods, and may lead to the (protandrous) cultivars release pollen from the catkins time and expense of re-planting. It is vital that new first, and later the stigmas become receptive. Type cultivars be chosen with care since a productive pecan II (protogynous) cultivars have stigmas that become orchard can last for generations. receptive first and the pollen is shed after the flowers Growers naturally want to know what the “best” have been fertilized. In natural pecan stands about one variety is to plant. Blanket recommendations should half of the trees will be Type I and the other half Type not be made because every orchard situation is II. -

U.S. Pecan Market Insight

AGRICULTURAL FINANCE U.S. Pecan Market Insight April 15, 2021 Executive Summary The U.S. pecan industry has endured trade wars, hurricanes, and import competition in recent years. However, we still expect U.S. growers will likely benefit from positive long-term fundamentals. U.S. commercial pecan producers have increased yields and profitability by converting native orchards to more improved tree varieties. Additionally, the U.S. already accounts for a significant share of global production. And as pecans’ popularity continues to rise among a growing global middle class, increasingly productive U.S. growers are well-positioned to capitalize on expanding demand. MetLife Investment Management 2 Improving Productivity The composition of the U.S. pecan industry Figure 1 | Average Pecan Yield (2016-20, in-shell, pounds per acre) has shifted significantly over the last ten years.1 Historically, pecans were produced 2500 in native orchards in Georgia and Texas, which generate highly variable output due to 2000 alternate bearing. In the early 2000s, more 1500 modern orchards began to appear in Arizona and New Mexico. Lower rainfall in the 1000 region forced growers to invest in irrigation 500 and more actively manage their orchards, compared to native groves. Growers in 0 the U.S. Southwest planted improved New Mexico Arizona Georgia Texas tree varieties and optimized management Source: USDA, MIM practices like spacing, irrigation systems, and harvest techniques. The climate also tends to be more stable in that region allowing Figure 2 | U.S. Pecan Production by Tree Variety farmers to better control disease. As a (mil. lbs.) result, Arizona and New Mexico growers 450 have achieved higher yields than those in 400 Georgia—typically the leading U.S. -

COCONUT PECAN CRUSTED CHICKEN Bell Pepper & Onion Cauliflower “Rice,” Chipotle Aïoli with Lime

COCONUT PECAN CRUSTED CHICKEN Bell pepper & onion cauliflower “rice,” chipotle aïoli with lime COOK TIME SERVINGS CALORIES PER SERVING NET CARBS PER SERVING MENU 25 MIN 2 600 14 GRAMS KETO // PALEO // GLUTEN-FREE Crunchy coated chicken is always a recipe INGREDIENTS (8 ITEMS) WHAT YOU’LL NEED for success. This gluten-free version swaps 1 ¾ oz Green bell pepper large sauté pan breadcrumbs for a flavorful combination of 1 whole Yellow onion baking sheet shredded coconut and buttery pecans. They’re ¼ oz Shredded coconut T measuring cup & spoons pulsed together until finely ground, then mounded ½ oz Pecans T food processor atop chicken cutlets. The chicken is roasted to 2 (5 oz) Chicken cutlets* thermometer juicy perfection while the crust turns crunchy and 1 ¾ oz Chipotle aïoli with lime E oven mitt deliciously toasty. It’s served atop cauliflower “rice” 2 cups Cauliflower “rice” cooking oil with studded bell pepper, onion, and roasted red 1 oz Roasted red peppers salt & pepper peppers, then finished with a drizzle of chipotle aïoli with lime for some spicy-smoky richness. ALLERGENS T TREE NUTS (coconut, pecans) E EGGS KING O FO O R C If you ordered the 4-serving version of this meal, 4 refer to the guidelines in Step 1. Certified gluten-free by the Gluten Intolerance *Chicken is fully cooked when internal temperature reaches 165 degrees. Group’s Gluten-Free Safe Spot Program. Wash and dry fresh produce. Wash hands and surfaces after handling raw poultry. Consuming raw or undercooked poultry GREEN CHEF IS PROUD to be a USDA Certified Organic company. -

NIDA TRADING BULK NUTS Wholesale Price Sheet

Minimum Order: (1) Case NIDA TRADING TOLL FREE 888-424-6432 Roasting: Add $.15/Lb LOCAL 815-334-0730 Prices Subject to Final Confirmation BULK NUTS FAX 815-334-0731 Local delivery $5.00 Wholesale Price Sheet www.nidatrading.com NO RETAIL SALES CONFIRM PRICES AT TIME OF ORDER EFFECTIVE DATE: 9/20/2021 Case Price Price Case Price Price Wt Per Lb Per Cs Wt Per Lb Per Cs PECANS Fancy Jr Mammoth Pecan Halves 30 $5.95 $178.50 OTHER NUTS Brazils 44 $ 7.95 $ 349.80 Fancy Topper Pecan Halves 30 $5.95 $178.50 AND SEEDS Filberts 25 $ 4.50 $ 112.50 Fancy Pecan Pieces 30 $4.25 $127.50 Blanched Filberts 25 $ 5.50 $ 137.50 Choice Pecan Pieces 30 $4.15 $124.50 Macadamia Style 1 . 25 $ 12.75 $ 318.75 Midget Pecan Pieces 30 $4.00 $120.00 Macadamia Style 4 25 $ 11.50 $ 287.50 Pecan Meal 30 $3.95 $118.50 Inshell Pistachios 25 $ 6.75 $ 168.75 Shelled Whole Pistachio 25 $ 10.50 $ 262.50 Pepitas 25 $ 3.50 $ 87.50 WALNUTS Walnut Halves & Pieces 25 $3.85 $96.25 Pine Nuts 27.5 $ 18.00 $ 495.00 Walnut Medium Pieces 30 $3.85 $115.50 Shelled Sunflower Kernel 50 $ 1.65 $ 82.50 Walnut Small Pieces 30 $3.95 $118.50 Praline Pecan Pieces 25 $ 6.00 $ 150.00 Walnut Nibbs 30 $3.95 $118.50 PEANUTS Blanched Runner Peanuts 30 $1.45 $43.50 MIXES Deluxe Mix Nuts RS 25 $ 5.00 $ 125.00 Spanish Peanuts Raw 30 $1.85 $55.50 Mix Nuts with Peanuts 25 $ 3.80 $ 95.00 Granulated Peanuts 30 $1.80 $54.00 Bakers Mix Raw 25 $ 5.40 $ 135.00 Peanut Butter 35 $1.60 $56.00 Hot N Honey Bar Mix 20 $ 1.90 $ 38.00 Honey Roasted Peanut 25 $2.50 $62.50 Honey Cheddar Bar Mix 20 $ 1.90 $ 38.00 Hot Cheddar -

Brazil Nut: Nutritional Benefits from a Unique Combination of Antioxidants

Journal of International Society for Food Bioactives Nutraceuticals and Functional Foods Review J. Food Bioact. 2020;9:36–39 Brazil nut: nutritional benefits from a unique combination of antioxidants Alan Giovanini de Oliveira Sartoria*, Marisa A.B. Regitano-d’Arcea and Leif H. Skibstedb aDepartment of Agri-food Industry, Food and Nutrition, Luiz de Queiroz College of Agriculture, University of São Paulo, Piracicaba, SP, Brazil bDepartment of Food Science, Faculty of Science, University of Copenhagen, Frederiksberg, Denmark *Corresponding author: Alan Giovanini de Oliveira Sartori, Department of Agri-food Industry, Food and Nutrition, Luiz de Queiroz Col- lege of Agriculture, University of São Paulo, Piracicaba, SP, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected] DOI: 10.31665/JFB.2020.9216 Received: March 27, 2020; Revised received & accepted: March 31, 2020 Citation: de Oliveira Sartori, A.G, Regitano-d’Arce, M.A.B., and Skibsted, L.H. (2020). Brazil nut: nutritional benefits from a unique com- bination of antioxidants. J. Food Bioact. 9: 36–39. Abstract Brazil nut is the seed of the Bertholletia excelsa tree, which grows naturally in the rainforests of South America. The production chain is environmentally sustainable as seeds are collected from the hard-shelled indehiscent fruits as they fall on the forest floor, without the need of deforestation. Brazil nut is among the most popular and commercially important tree nuts, and a reduced risk of coronary heart disease among other health benefits have been related to its consumption. A high content of both soluble and bound phenolic antioxidants, especially in the brown skin of the kernel, partly explains this positive health effect together with a high content of oleic acid and linoleic acid. -

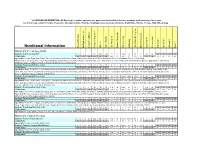

Nutritional Information

* ALLERGEN INFORMATION: All Stuckey's candies and nuts are processed in facilities that use peanuts and a variety of tree nuts. Each item may contain Peanuts, Pistachios, Macadamia Nuts, Walnuts, Soy(Soybeans), Cashews, Almonds, Brazil Nuts, Filberts, Pecans, Milk, Wheat, Egg 20111017 Nutritional Information Allergen Information Net Weight In Ounces (oz) Servings Per Container Serving Size (In grams) ** Calories Calories From Fat Total Fat in grams Saturated Fat in grams Cholesterol in mg Sodium in mg Total Carbohydrate in grams Dietary Fiber in grams Sugars in grams Protein in grams Vitamin A in % Vitamin C in % Calcium in % Iron in % Stuckey's Pecan Log Rolls Stuckey's 2 oz Pecan Log Roll * 2 1 56.7 270 140 15 1.5 0mg 70 32 2 24 3g na na na na % Daily Value na na na na na na 24% 9% 0% 3% 11% 7% na na 0% 0% 4% 2% Ingredients: Pecans, Sugar Corn Syrup, Sweetened Condensed Milk, Invert Sugar, Hydrogenated Soybean Oil, Diced Maraschino Cherries (Containing: Cherries, Corn Syrup, High Fructose Corn Syrup, Water, Citric Acid, Natural and Artificial Flavors, Potassium Sorbate and Sodium Benzoate Added As Preservatives, FD & C Red # 40 and Sulfur Dioxide), Egg Albumen, Salt, Natural & Artificial Flavors, Lecithin(an emulsifier), Sodium Bicarbonate( a leavening agent) Stuckey's Pecan Log Roll (4 oz Cello) * 4 3 43 180 80 8 1 0 35 27 <1g 26 1g na na na na % Daily Value na na na na na na 13% 6% 0% 1% 9% 2% na na 0% 0% 0% 2% Ingredients: Sugar, Pecan Pieces, Corn Syrup, Evaporated Milk (Whole Milk, Dipotassium Phosphate, Carrageenan and Vitamin -

Sweet Pecan Plant Fact Sheet

Plant Fact Sheet status (e.g. threatened or endangered species, state PECAN noxious status, and wetland indicator values). Carya illinoinensis (Wangenh.) Description and Adaptation K. Koch Pecan is a large tree to 150 feet with a broad rounded Plant Symbol = CAIL2 crown. It is the largest of all the hickories. It produces flowers from March to May with both male and female flowers on the same tree. Leaves are alternate, odd- Contributed by: USDA NRCS East Texas Plant Materials pinnately compound with 9-17 leaflets. The fruit is a nut Center 1 to 2 inches long and ½ to l inch in diameter. The nut is encased in a thin husk which is divided into sections which open in the fall at maturity. The bark is grayish brown to light brown with flattened ridges and narrow fissures. The wood is reddish brown with lighter sapwood, brittle and hard. Pecan grows best in loam soils which are well drained without prolonged flooding. Pecan is adapted to areas with a minimum of 30 inches of average rainfall. Pecan distribution from USDA-NRCS Plants database Establishment Due to stratification requirements for the nut to sprout, establishment is best with nursery grown seedlings which are planted in the fall or early winter. In mass plantings Robert Mohlenbrock bare root seedlings can be planted by hand or machine. USDA, NRCS, Wetland Science Institute Care should be taken with root placement and planting @PLANTS depth. The root collar should be planted at the same depth as grown in the nursery. Alternate Names Sweet pecan, Illinois nut, faux hickory, pecan hickory, Management pecan nut, pecan tree Weed control and fertilization are important considerations for maximizing nut production.