Maritime Havens in Earlier Prehistoric Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arrow Company Profile

Fact Sheet Executive Officers Arrow Company Michael J. Long Chairman, President and Chief Executive Officer Profile Paul J. Reilly Arrow is a global provider of products, services, and solutions to industrial Executive Vice President, Finance and Operations, and Chief Financial Officer and commercial users of electronic components and enterprise computing solutions, with 2012 sales of $20.4 billion. Arrow serves as a supply channel Peter S. Brown partner for over 100,000 original equipment manufacturers, contract Senior Vice President, General Counsel manufacturers, and commercial customers through a global network of more and Secretary than 470 locations in 55 countries. A Fortune 150 company with 16,500 Andrew S. Bryant employees worldwide, Arrow brings the technology solutions of its suppliers President, Global Enterprise to a breadth of markets, including industrial equipment, information systems, Computing Solutions automotive and transportation, aerospace and defense, medical and life Vincent P. Melvin sciences, telecommunications and consumer electronics, and helps customers Vice President and Chief Information Officer introduce innovative products, reduce their time to market, and enhance their M. Catherine Morris overall competiveness. Senior Vice President and Chief Strategy Officer FAST FACTS Eric J. Schuck President, Global Components > Ticker Symbol: ARW (NYSE) > Fortune 500 Ranking1: 141 Gretchen K. Zech > 2012 Sales: $20.4 billion > Employees Worldwide: 16,500 Senior Vice President, Global Human - Global Components: $13.4 > Customers Worldwide: 100,000 Resources billion - Global Enterprise Computing > Industry: Electronic Solutions: $7 billion Components and Computer Products Distribution 20122012 Sales Sales by Geographic by Geographic Region Region > 2012 Net Income: $506.3 million > Founded: 1935 19% ASIA/PACIFIC > 2012 Operating Income: > Incorporated: 1946 52% AMERICAS $804.1 million > Public: 1961 > 2012 EPS: $4.56 > Website: www.arrow.com > Locations: more than 470 worldwide 29% 1 Ranking of the largest U.S. -

On the Mechanics of the Bow and Arrow 1

On the Mechanics of the Bow and Arrow 1 B.W. Kooi Groningen, The Netherlands 1983 1B.W. Kooi, On the Mechanics of the Bow and Arrow PhD-thesis, Mathematisch Instituut, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, The Netherlands (1983), Supported by ”Netherlands organization for the advancement of pure research” (Z.W.O.), project (63-57) 2 Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Prefaceandsummary.............................. 5 1.2 Definitionsandclassifications . .. 7 1.3 Constructionofbowsandarrows . .. 11 1.4 Mathematicalmodelling . 14 1.5 Formermathematicalmodels . 17 1.6 Ourmathematicalmodel. 20 1.7 Unitsofmeasurement.............................. 22 1.8 Varietyinarchery................................ 23 1.9 Qualitycoefficients ............................... 25 1.10 Comparison of different mathematical models . ...... 26 1.11 Comparison of the mechanical performance . ....... 28 2 Static deformation of the bow 33 2.1 Summary .................................... 33 2.2 Introduction................................... 33 2.3 Formulationoftheproblem . 34 2.4 Numerical solution of the equation of equilibrium . ......... 37 2.5 Somenumericalresults . 40 2.6 A model of a bow with 100% shooting efficiency . .. 50 2.7 Acknowledgement................................ 52 3 Mechanics of the bow and arrow 55 3.1 Summary .................................... 55 3.2 Introduction................................... 55 3.3 Equationsofmotion .............................. 57 3.4 Finitedifferenceequations . .. 62 3.5 Somenumericalresults . 68 3.6 On the behaviour of the normal force -

Ohio Archaeologist Volume 43 No

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST VOLUME 43 NO. 2 SPRING 1993 Published by THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF OHIO The Archaeological Society of Ohio MEMBERSHIP AND DUES Annual dues to the Archaeological Society of Ohio are payable on the first TERM of January as follows: Regular membership $17.50; husband and wife EXPIRES A.S.O. OFFICERS (one copy of publication) $18.50; Life membership $300.00. Subscription to the Ohio Archaeologist, published quarterly, is included in the member 1994 President Larry L. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue SE, East ship dues. The Archaeological Society of Ohio is an incorporated non Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 profit organization. 1994 Vice President Stephen J. Parker, 1859 Frank Drive, Lancaster, OH 43130, (614)653-6642 BACK ISSUES 1994 Exec. Sect. Donald A. Casto, 138 Ann Court, Lancaster, OH Publications and back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist: Ohio Flint Types, by Robert N. Converse $10.00 add $1.50 P-H 43130,(614)653-9477 Ohio Stone Tools, by Robert N. Converse $ 8.00 add $1.50 P-H 1994 Recording Sect. Nancy E. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue Ohio Slate Types, by Robert N. Converse $15.00 add $1.50 P-H SE. East Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 The Glacial Kame Indians, by Robert N. Converse .$20.00 add $1.50 P-H 1994 Treasurer Don F. Potter, 1391 Hootman Drive, Reynoldsburg, 1980's & 1990's $ 6.00 add $1.50 P-H OH 43068, (614)861-0673 1970's $ 8.00 add $1.50 P-H 1998 Editor Robert N. Converse, 199 Converse Dr., Plain City, OH 1960's $10.00 add $1.50 P-H 43064,(614)873-5471 Back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist printed prior to 1964 are gener ally out of print but copies are available from time to time. -

Stones, Bones, and States: a New Approach to the Neolithic Revolution

1 Stones, Bones, and States: A New Approach to the Neolithic Revolution Richard H. Steckel and John Wallis February 19, 2007 The invention of agriculture, the wide spread shift to a sedentary lifestyle, and the growth of large population centers began around 10,000 years ago in what we now call the Neolithic revolution. This profound change in human activity marks the beginning of modern human society and has long been of interest to economists, anthropologists, and social scientists in general. Was it caused by a shift in relative prices due to climate, population pressure, or changes in the animal environment? Did it result from technological innovation in human knowledge about the physical world? Was institutional change a catalyst? Early research was highly speculative, with abundant explanations built on little data. New evidence from archeology and anthropology has eliminated some hypotheses and raised possibilities for answering more specific questions. This paper contributes to both the Neolithic empirical evidence and the theoretical questions about the Neolithic revolution. We propose a theoretical answer to how larger social groups were organized. A sedentary life-style was necessary for settled agriculture, and the shift to larger population units occurred contemporaneously with, and may have even preceded, the spread of new agricultural techniques. We then focus on the paradoxes inherent in the question: why did people move into towns and cities? Urban living came at a substantial cost. Accumulating evidence from skeletons, which we discuss below, shows that Neolithic cities and towns were unhealthy. Their residents were smaller in stature than hunter-gatherers and their bones had relatively more lesions indicating dental decay, infections and other signs of physiological stress. -

Prehistoric Artefact Box: Complete Box

PREHISTORIC ARTEFACT BOX PREHISTORIC ARTEFACT BOX: COMPLETE BOX 1 Antler Retoucheur 11 Leather Cup 2 Flint Retoucheur 12 Flint Scrapers [1 large & 4 x small] in pouch 3 Hammer Stone 13 Flint Arrowheads [x2] in box/pouch 4 Comb 14 Bronze Age Flint arrowhead in pouch 5 Needle & Thread 15 Hair Ornaments [x 2] in pouch 6 Slate Arrow 16 Mesolithic Arrow 7 Small Knife 17 Goddess Figurine 8 Resin Stick 18 Antler Tool 9 Bead Necklace 19 Prehistoric Loan Box- Risk Assessment 10 Hand Axe and Leather Covers 20 Artefact Box Booklet-Prehistoric Acknowledgements The artefacts were made by Emma Berry and Andrew Bates of Phenix Studios Ltd of Hexham, Northumberland. http://www.phenixstudios.com/ ARTEFACT BOX: PREHISTORIC Item: 1 Brief Description: Antler Retoucheur Further Information: This tool is made from antler. It was used to retouch flints-that means it was used to sharpen it by carefully chipping away small flakes away from a stone tool’s edge that had become blunt through use. Mesolithic and Neolithic flaked tools were made with a lot of retouching, as they were very small and very fine. Even Palaeolithic tools could be sharpened by retouching. Explore: The periods of prehistory covered in this artefact box are called: the Palaeolithic, Mesolithic and Neolithic Ages (the Old, Middle and New Stone Ages) and the Bronze Age. What “Age” do we live in today? The Steel Age? The Plastic Age? Is everything we use made of this material? To find out more about each of these Stone Age periods follow this link: http://www.bbc.co.uk/guides/zpny34j#z98q2hv ARTEFACT BOX: PREHISTORIC Item: 2 Brief Description: Flint Retoucheur Further Information: The tip of this tool was made from antler and the handle is lime wood. -

Section Iv: Students Policy 4230 Possession of Weapons, Alcohol, And/Or Controlled Substances/Illegal Drugs in School

SECTION IV: STUDENTS POLICY 4230 POSSESSION OF WEAPONS, ALCOHOL, AND/OR CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES/ILLEGAL DRUGS IN SCHOOL In order to provide a safe environment for the students and staff of the Broken Arrow School District, the Board of Education adopts this policy prohibiting the possession of weapons, alcohol, controlled substances, illegal drugs and replicas or facsimiles of dangerous weapons. Weapons, including but not limited to firearms, alcohol, controlled substances and illegal drugs are a threat to the safety of the students and staff of the Broken Arrow School District. In addition, possession of weapons, alcohol, controlled substances or illegal drugs disrupts the educational process and interferes with the normal operation of the school district. For the foregoing reasons and except as specifically provided below, possession of weapons, alcohol, controlled substances and illegal drugs, as defined in this policy, while at school, at a school- sponsored activity, in transit to or from a school-sponsored activity, or on a school vehicle, is prohibited. For the purposes of this regulation, "School" includes all school district property, the entire school campus, parking lots, athletic fields, and district vehicles. "School" also includes off-district property when the student is on the property for the purpose of participating in a school or district-sponsored event or is participating in an event in which the student is representing the district. "School" covers any school bus or vehicle used for transportation of students or teachers, lodging and meal locations, event sites, and all other locations where a student is present while participating in or attending a district or school sponsored event. -

Quartz Technology in Scottish Prehistory

Quartz technology in Scottish prehistory by Torben Bjarke Ballin Scottish Archaeological Internet Report 26, 2008 www.sair.org.uk Published by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, www.socantscot.org.uk with Historic Scotland, www.historic-scotland.gov.uk and the Council for British Archaeology, www.britarch.ac.uk Editor Debra Barrie Produced by Archétype Informatique SARL, www.archetype-it.com ISBN: 9780903903943 ISSN: 1473-3803 Requests for permission to reproduce material from a SAIR report should be sent to the Director of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, as well as to the author, illustrator, photographer or other copyright holder. Copyright in any of the Scottish Archaeological Internet Reports series rests with the SAIR Consortium and the individual authors. The maps are reproduced from Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of The Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. ©Crown copyright 2001. Any unauthorized reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Historic Scotland Licence No GD 03032G, 2002. The consent does not extend to copying for general distribution, advertising or promotional purposes, the creation of new collective works or resale. ii Contents List of illustrations. vi List of tables . viii 1 Summary. 1 2 Introduction. 2 2.1 Project background, aims and working hypotheses . .2 2.2 Methodology . 2 2.2.1 Raw materials . .2 2.2.2 Typology. .3 2.2.3 Technology . .3 2.2.4 Distribution analysis. 3 2.2.5 Dating. 3 2.3 Project history . .3 2.3.1 Pilot project. 4 2.3.2 Main project . -

Stone Age Essex a Teacher's Guide

Stone Age Essex A Teacher’s Guide Colchester and Ipswich Museums 1 Table of contents Overview of Stone Age Essex 3 Stone Age Timeline 7 Stone Age Glossary 8 Recommended Resources 9 Recommended Additional Learning 10 Stone Age Objects 11 Activity Examples 15 2 Overview of Stone Age Essex The Stone Age had three distinct periods: the Palaeolithic (Old Stone Age), the Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) and the Neolithic (New Stone Age). The people from each of these periods had different levels of technology and methods of survival. Palaeolithic The Palaeolithic began in Britain around 800,000 years ago when early humans, including Homo antecessor and Homo neanderthalensis, crossed the land bridge that connected Britain to mainland Europe. The cold temperatures of the last Ice Age had left most of Britain covered in ice and snow, rendering it uninhabitable. Interglacial periods, when the ice sheet retreated and the temperature warmed, allowed early humans to cross the land bridge and take advantage of the rich flora and fauna in Britain. Palaeolithic people who crossed the land bridge into Britain were hunter-gatherers. They developed tools made of stone to exploit the environment around them. Evidence of butchery on animal bones shows that they used these tools to hunt species including mammoth, red deer, hare and antelope. PALEOLITHIC SITES (Essex and Suffolk) Marks Tey Why is Marks Tey important? In the last Ice Age, most of Britain was covered by an ice sheet. The area that is now Marks Tey lay at the easternmost edge of the ice sheet. This was the edge of the habitable world for both humans and animals. -

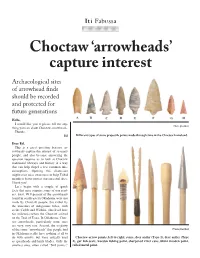

2011.07 Choctaw Arrowheads Capture Interest

Iti Fabussa Choctaw ‘arrowheads’ capture interest Archaeological sites of arrowhead finds should be recorded and protected for future generations Hello, I would like you to please tell me any- Photo provided thing you can about Choctaw arrowheads. Thanks, Ed Different types of stone projectile points made through time in the Choctaw homeland. Dear Ed, This is a great question because ar- rowheads capture the interest of so many people, and also because answering the question requires us to look at Choctaw traditional lifeways and history in a way that can help dispel a few common mis- conceptions. Opening this discussion might even raise awareness to help Tribal members better protect our ancestral sites. Thank you! Let’s begin with a couple of quick facts that may surprise some of our read- ers. First, 99.9 percent of the arrowheads found in southeastern Oklahoma were not made by Choctaw people, but rather by the ancestors of indigenous tribes, such as the Caddo and Wichita, who lived here for millennia before the Choctaw arrived on the Trail of Tears. In Oklahoma, Choc- taw arrowheads, particularly stone ones are very, very rare. Second, the majority of the stone “arrowheads” that people find Photo provided in Oklahoma really have nothing at all to do with arrows, but were actually used Choctaw arrow points, left to right; stone, deer antler (Type 1), deer antler (Type as spearheads and knife blades. Only the 2), gar fish scale, wooden fishing point, sharpened river cane, blunt wooden point, smallest ones, often called “bird points,” rolled metal point. were put on the end of arrows. -

"Dangerous Weapon" Is Any Firearm, Whether Lo

FRIDLEY CITY CODE CHAPTER 103. DANGEROUS WEAPONS (Ref. 27, 176, 291, 676, 730, 1047) 103.01. DEFINITION A "dangerous weapon" is any firearm, whether loaded or unloaded, or any device designed as a weapon and capable of producing death or great bodily harm, or any other device or instrumentality which, in the manner it is used or intended to be used, is calculated or likely to produce death or great bodily harm. The term "dangerous weapon" includes, but is not limited to, the following: 1. All firearms. 2. Bows and arrows, and cross bows. 3. All instruments used to expel, at high velocity, pellets of any kind including, but not limited to, B-B guns and air rifles. 4. Sling shots. 5. Black jacks, nunchakus, clubs or like objects. 6. Metal knuckles. 7. Daggers, dirks, and knives. 8. Wrist rockets. 103.02. PROHIBITED ACTS Whoever does any of the following is guilty of a misdemeanor: 1. Recklessly handles or uses a dangerous weapon or explosive so as to endanger the safety of another. 2. Aims any dangerous weapon, whether loaded or not, at or toward any human being. 3. Manufactures or sells for any unlawful purpose any weapon known as a sling shot, black jack, nunchakus, club, wrist rocket, bow and arrow, crossbow, or like object. 4. Manufactures, transfers or possesses metal knuckles or a switch blade knife opening automatically. 5. Possesses any other dangerous article or substance for the purpose of being used unlawfully as a weapon against another. Fridley City Code Section 103.04.5 6. Sells or has in their possession any device designed to silence or muffle the discharge of a firearm. -

Historic American Indian Tribes of Ohio 1654-1843

Historic American Indian Tribes of Ohio 1654-1843 Ohio Historical Society www.ohiohistory.org $4.00 TABLE OF CONTENTS Historical Background 03 Trails and Settlements 03 Shelters and Dwellings 04 Clothing and Dress 07 Arts and Crafts 08 Religions 09 Medicine 10 Agriculture, Hunting, and Fishing 11 The Fur Trade 12 Five Major Tribes of Ohio 13 Adapting Each Other’s Ways 16 Removal of the American Indian 18 Ohio Historical Society Indian Sites 20 Ohio Historical Marker Sites 20 Timeline 32 Glossary 36 The Ohio Historical Society 1982 Velma Avenue Columbus, OH 43211 2 Ohio Historical Society www.ohiohistory.org Historic American Indian Tribes of Ohio HISTORICAL BACKGROUND In Ohio, the last of the prehistoric Indians, the Erie and the Fort Ancient people, were destroyed or driven away by the Iroquois about 1655. Some ethnologists believe the Shawnee descended from the Fort Ancient people. The Shawnees were wanderers, who lived in many places in the south. They became associated closely with the Delaware in Ohio and Pennsylvania. Able fighters, the Shawnees stubbornly resisted white pressures until the Treaty of Greene Ville in 1795. At the time of the arrival of the European explorers on the shores of the North American continent, the American Indians were living in a network of highly developed cultures. Each group lived in similar housing, wore similar clothing, ate similar food, and enjoyed similar tribal life. In the geographical northeastern part of North America, the principal American Indian tribes were: Abittibi, Abenaki, Algonquin, Beothuk, Cayuga, Chippewa, Delaware, Eastern Cree, Erie, Forest Potawatomi, Huron, Iroquois, Illinois, Kickapoo, Mohicans, Maliseet, Massachusetts, Menominee, Miami, Micmac, Mississauga, Mohawk, Montagnais, Munsee, Muskekowug, Nanticoke, Narragansett, Naskapi, Neutral, Nipissing, Ojibwa, Oneida, Onondaga, Ottawa, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, Peoria, Pequot, Piankashaw, Prairie Potawatomi, Sauk-Fox, Seneca, Susquehanna, Swamp-Cree, Tuscarora, Winnebago, and Wyandot. -

Dynamics of the Bow and Arrow

EN 4: Dynamics and Vibrations Brown University, Division of Engineering LABORATORY 1: DYNAMICS OF THE BOW AND ARROW Compound Bow Recurve Bow Long Bow SAFETY You will be testing three very powerful, full sized bows. The bows release a lot of energy very quickly, and can cause serious injury if they are used improperly. • Do not place any part of your body between the string and the bow at any time; • Stand behind the loading stage while the arrow is being released; • Do not pull and release the string without an arrow in place. If you do so, you will break not only the bow, but also yourself and those around you! 1. Introduction In Engineering we often use physical principles and mathematical analyses to achieve our goals of innovation. In this laboratory we will use simple physical principles of dynamics, work and energy, and simple analyses of calculus, differentiation and integration, to study engineering aspects of a projectile launching system, the bow and arrow. A bow is an engineering system of storing elastic energy effectively and exerting force on the mass of an arrow efficiently, to convert stored elastic energy of the bow into kinetic energy of the arrow. Engineering design of the bow and arrow system has three major objectives; (1) to store the elastic energy in the bow effectively within the capacity of the archer to draw and hold the bow comfortably while aiming, (2) to maximize the conversion of the elastic energy of the bow into the kinetic energy of the arrow, and (3) to keep the operation simple and within the strength of the bow and arrow materials system.