An End to ``Civil War Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

Index Note: page numbers in italics denote illustrations or maps Abbey Theatre 175 sovereignty 390 Abbot, Charles 28 as Taoiseach 388–9 abdication crisis 292 and Trimble 379, 409, 414 Aberdeen, Earl of 90 Aiken, Frank abortion debate 404 ceasefire 268–9 Academical Institutions (Ireland) Act 52 foreign policy 318–19 Adams, Gerry and Lemass 313 assassination attempt 396 and Lynch 325 and Collins 425 and McGilligan 304–5 elected 392 neutrality 299 and Hume 387–8, 392, 402–3, 407 reunification 298 and Lynch 425 WWII 349 and Paisley 421 air raids, Belfast 348, 349–50 St Andrews Agreement 421 aircraft industry 347 on Trimble 418 Aldous, Richard 414 Adams, W.F. 82 Alexandra, Queen 174 Aer Lingus 288 Aliens Act 292 Afghan War 114 All for Ireland League 157 Agar-Robartes, T.G. 163 Allen, Kieran 308–9, 313 Agence GénéraleCOPYRIGHTED pour la Défense de la Alliance MATERIAL Party 370, 416 Liberté Religieuse 57 All-Ireland Committee 147, 148 Agricultural Credit Act 280 Allister, Jim 422 agricultural exports 316 Alter, Peter 57 agricultural growth 323 American Civil War 93, 97–8 Agriculture and Technical Instruction, American note affair 300 Dept of 147 American War of Independence 93 Ahern, Bertie 413 Amnesty Association 95, 104–5, 108–9 and Paisley 419–20 Andrews, John 349, 350–1 resignation 412–13, 415 Anglesey, Marquis of 34 separated from wife 424 Anglicanism 4, 65–6, 169 Index 513 Anglo-American war 93 Ashbourne Purchase Act 133, 150 Anglo-Irish Agreement (1938) 294, 295–6 Ashe, Thomas 203 Anglo-Irish Agreement (1985) Ashtown ambush 246 aftermath -

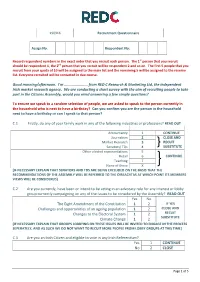

RED C Recruitment Questionnaire

190916 Recruitment Questionnaire Assign No. Respondent No: Record respondent numbers in the exact order that you recruit each person. The 1st person that you recruit should be respondent 1, the 2nd person that you recruit will be respondent 2 and so on. The first 5 people that you recruit from your quota of 10 will be assigned to the main list and the remaining 5 will be assigned to the reserve list. Everyone recruited will be contacted in due course. Good morning/afternoon. I'm ...................... from RED C Research & Marketing Ltd, the independent Irish market research agency. We are conducting a short survey with the aim of recruiting people to take part in the Citizens Assembly, would you mind answering a few simple questions? To ensure we speak to a random selection of people, we are asked to speak to the person currently in the household who is next to have a birthday? Can you confirm you are the person in the household next to have a birthday or can I speak to that person? C.1 Firstly, do any of your family work in any of the following industries or professions? READ OUT Accountancy 1 CONTINUE Journalism 2 CLOSE AND Market Research 3 RECUIT Senators/ TDs 4 SUBSTITUTE Other elected representatives 5 Retail 6 CONTINUE Teaching 7 None of these X [IF NECESSARY EXPLAIN THAT SENATORS AND TDS ARE BEING EXCLUDED ON THE BASIS THAT THE RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE ASSEMBLY WILL BE REFERRED TO THE OIREACHTAS AT WHICH POINT ITS MEMBERS VIEWS WILL BE CONSIDERED] C.2 Are you currently, have been or intend to be acting in an advocacy role for any -

The Irish Left Over 50 Years

& Workers’ Liberty SolFor siociadl ownershaip of the branks aind intdustry y No 485 7 November 2018 50p/£1 The DEMAND EVERY Irish left over 50 LABOUR MP years VOTES AGAINST See pages 6-8 The May government and its Brexit process are bracing themselves to take the coming weeks at a run, trying to hurtle us all over a rickety bridge. Yet it looks like they could be saved by some Labour MPs voting for the To - ries’ Brexit formula. More page 5 NUS set to gut BREXIT democracy Maisie Sanders reports on financial troubles at NUS and how the left should respond. See page 3 “Fake news” within the left Cathy Nugent calls for the left to defend democracy and oppose smears. See page 10 Join Labour! Why Labour is losing Jews See page 4 2 NEWS More online at www.workersliberty.org Push Labour to “remain and reform” May will say that is still the ulti - trade deals is now for the birds. mate objective, but for not for years Britain will not be legally able to in - to come. troduce any new deals until the fu - The second option, which is often ture long-term treaty relationship John Palmer talked to equated with “hard” Brexit, is no with the EU has been negotiated, at deal. That is a theoretical possibil - the end of a tunnel which looks Solidarity ity. But I don’t think in practice cap - longer and longer. ital in Britain or elsewhere in The job of the left, the supporters S: You’ve talked about a Europe has any interest in that, and of the Corbyn leadership of the “Schrödinger’s Brexit”.. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Evaluation of the Irish Referendum on Lisbon Treaty, June 2008

Evaluation of the Irish Referendum on Lisbon Treaty, June 2008 Markus Schmidgen democracy international is a network promoting direct democracy. Our basic goal is the establishment of direct democracy (initiative and referendum) as a complement to representative democracy within the European Union and in the nation states. We also work on the general democratisation of the European Union, democratic reform and more direct and participatory democracy worldwide. http://www.democracy-international.org Written by Markus Schmidgen Layout: Ronald Pabst Proof-reading (contents):, Gayle Kinkead, Ronald Pabst, Thomas Rupp Proof-reading (language): Sheena A. Finley, Warren P. Mayr Advice: Dr. Klaus Hofmann, Bruno Kaufmann, Frank Rehmet Please refer all questions to: [email protected] Published by democracy international V 0.9 (4.9.2008) Evaluation of the Irish Referendum on Lisbon Treaty, June 2008 I Introduction This report examines the process of the Irish CONTENT referendum on the Treaty of Lisbon. The referendum was held on June 12, 2008 and was the only referendum on this treaty. The evaluation is I INTRODUCTION .......................................... 3 based on the criteria set by the Initiative and Referendum Institute Europe (IRIE). These criteria are internationally recognized as standards to II SETTING...................................................... 4 measure how free and fair a referendum process is conducted. This enables the reader to compare the II.1 Background ................................................... 4 Irish Lisbon referendum to other referendums and to identify the points that could be improved as well II.2 Actors ............................................................. 4 as those that are an example to other nations. II.3 Evaluation...................................................... 7 We at Democracy International and our European partners have already published a series of reports on the EU constitutional referenda of 2005: Juan III CONCLUSION......................................... -

The Irish Party System Sistemul Partidelor Politice În Irlanda

The Irish Party System Sistemul Partidelor Politice în Irlanda Assistant Lecturer Javier Ruiz MARTÍNEZ Fco. Javier Ruiz Martínez: Assistant Lecturer of Polics and Public Administration. Department of Politics and Sociology, University Carlos III Madrid (Spain). Since September 2001. Lecturer of “European Union” and “Spanish Politics”. University Studies Abroad Consortium (Madrid). Ph.D. Thesis "Modernisation, Changes and Development in the Irish Party System, 1958-96", (European joint Ph.D. degree). Interests and activities: Steering Committee member of the Spanish National Association of Political Scientists and Sociologists; Steering committee member of the European Federation of Centres and Associations of Irish Studies, EFACIS; Member of the Political Science Association of Ireland; Founder of the Spanish-American Association of the University of Limerick (Éire) in 1992; User level in the command of Microsoft Office applications, graphics (Harvard Graphics), databases (Open Access) SPSSWIN and Internet applications. Abstract: The Irish Party System has been considered a unique case among the European party systems. Its singularity is based in the freezing of its actors. Since 1932 the three main parties has always gotten the same position in every election. How to explain this and which consequences produce these peculiarities are briefly explained in this article. Rezumat: Sistemul Irlandez al Partidelor Politice a fost considerat un caz unic între sistemele partidelor politice europene. Singularitatea sa este bazată pe menţinerea aceloraşi actori. Din 1932, primele trei partide politice ca importanţă au câştigat aceeaşi poziţie la fiecare scrutin electoral. Cum se explică acest lucru şi ce consecinţe produc aceste aspecte, se descrie pe larg în acest articol. At the end of the 1950s the term ‘system’ began to be used in Political Science coming from the natural and physical Sciences. -

The Ulster Women's Unionist Council and Ulster Unionism

“No Idle Sightseers”: The Ulster Women’s Unionist Council and Ulster Unionism (1911-1920s) Pamela Blythe McKane A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN POLITICAL SCIENCE YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO JANUARY 2015 ©Pamela Blythe McKane 2015 Abstract Title: “No Idle Sightseers”: The Ulster Women’s Unionist Council and Ulster Unionism (1911-1920s) This doctoral dissertation examines the Ulster Women’s Unionist Council (UWUC), an overlooked, but historically significant Ulster unionist institution, during the 1910s and 1920s—a time of great conflict. Ulster unionists opposed Home Rule for Ireland. World War 1 erupted in 1914 and was followed by the Anglo-Irish War (1919- 1922), the partition of Ireland in 1922, and the Civil War (1922-1923). Within a year of its establishment the UWUC was the largest women’s political organization in Ireland with an estimated membership of between 115,000 and 200,000. Yet neither the male- dominated Ulster unionist institutions of the time, nor the literature related to Ulster unionism and twentieth-century Irish politics and history have paid much attention to its existence and work. This dissertation seeks to redress this. The framework of analysis employed is original in terms of the concepts it combines with a gender focus. It draws on Rogers Brubaker’s (1996) concepts of “nation” as practical category, institutionalized form (“nationhood”), and contingent event (“nationness”), combining these concepts with William Walters’ (2004) concept of “domopolitics” and with a feminist understanding of the centrality of gender to nation. -

Electoral Processes Report | SGI Sustainable Governance Indicators

Electoral Processes Report Candidacy Procedures, Media Access, Voting and Registration Rights, Party Financing, Popular Decision-Making m o c . e b o d a . k c Sustainable Governance o t s - e g Indicators 2018 e v © Sustainable Governance SGI Indicators SGI 2018 | 1 Electoral Processes Indicator Candidacy Procedures Question How fair are procedures for registering candidates and parties? 41 OECD and EU countries are sorted according to their performance on a scale from 10 (best) to 1 (lowest). This scale is tied to four qualitative evaluation levels. 10-9 = Legal regulations provide for a fair registration procedure for all elections; candidates and parties are not discriminated against. 8-6 = A few restrictions on election procedures discriminate against a small number of candidates and parties. 5-3 = Some unreasonable restrictions on election procedures exist that discriminate against many candidates and parties. 2-1 = Discriminating registration procedures for elections are widespread and prevent a large number of potential candidates or parties from participating. Australia Score 10 The Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) is an independent statutory authority that oversees the registration of candidates and parties according to the registration provisions of Part XI of the Commonwealth Electoral Act. The AEC is accountable for the conduct of elections to a cross-party parliamentary committee, the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters (JSCEM). JSCEM inquiries into and reports on any issues relating to electoral laws and practices and their administration. There are no significant barriers to registration for any potential candidate or party. A party requires a minimum of 500 members who are on the electoral roll. -

Survey: English

The Economic and Social Research Institute 4 Burlington Road Dublin 4 Ph. 6671525 IRISH ELECTION SURVEY, SUMMER 2002 Interviewer’s Name ____________________ Interviewer’s Number Constituency Code Area Code Respondent Code Date of Interview: Day Month Time Interview Began (24hr clock) Introduction (Ask for named respondent) Good morning/afternoon/evening. I am from the Economic and Social Research Institute in Dublin. We have been commissioned by a team of researchers from Trinity College Dublin and University College Dublin to carry out a survey into the way people voted in the recent general election. You have been selected at random from the Electoral Register to participate in the survey. The interview will take about 60 minutes to complete and all information provided will be treated in the strictest confidence by the Economic and Social Research Institute. It will not be possible for anyone to identify your individual views or attitudes from the analysis undertaken on the data. __________________________________________________________________________________ SECTION A A1 First, I’d like to ask you a general question. What do you think has been the single most important issue facing Ireland over the last five years? ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ A2 How good or bad a job do you think the Fianna Fail/Progressive Democrat government did over the past five years in terms of _______________________ [the Main issue mentioned at A1 above]. Did they do a: Very Good Job......... 1 Good Job ......... 2 Bad Job ..... 3 Very Bad Job…… 4 Don’t know ..... 5 A3.1a Looking back on the recent general election campaign in May of this year, could you tell me if a candidate called to your home? Yes ...... -

A History of Modern Ireland 1800-1969

ireiana Edward Norman I Edward Norman A History of Modem Ireland 1800-1969 Advisory Editor J. H. Plumb PENGUIN BOOKS 1971 Contents Preface to the Pelican Edition 7 1. Irish Questions and English Answers 9 2. The Union 29 3. O'Connell and Radicalism 53 4. Radicalism and Reform 76 5. The Genesis of Modern Irish Nationalism 108 6. Experiment and Rebellion 138 7. The Failure of the Tiberal Alliance 170 8. Parnellism 196 9. Consolidation and Dissent 221 10. The Revolution 254 11. The Divided Nation 289 Note on Further Reading 315 Index 323 Pelican Books A History of Modern Ireland 1800-1969 Edward Norman is lecturer in modern British constitutional and ecclesiastical history at the University of Cambridge, Dean of Peterhouse, Cambridge, a Church of England clergyman and an assistant chaplain to a hospital. His publications include a book on religion in America and Canada, The Conscience of the State in North America, The Early Development of Irish Society, Anti-Catholicism in 'Victorian England and The Catholic Church and Ireland. Edward Norman also contributes articles on religious topics to the Spectator. Preface to the Pelican Edition This book is intended as an introduction to the political history of Ireland in modern times. It was commissioned - and most of it was actually written - before the present disturbances fell upon the country. It was unfortunate that its publication in 1971 coincided with a moment of extreme controversy, be¬ cause it was intended to provide a cool look at the unhappy divisions of Ireland. Instead of assuming the structure of interpretation imposed by writers soaked in Irish national feeling, or dependent upon them, the book tried to consider Ireland’s political development as a part of the general evolu¬ tion of British politics in the last two hundred years. -

Challenger Party List

Appendix List of Challenger Parties Operationalization of Challenger Parties A party is considered a challenger party if in any given year it has not been a member of a central government after 1930. A party is considered a dominant party if in any given year it has been part of a central government after 1930. Only parties with ministers in cabinet are considered to be members of a central government. A party ceases to be a challenger party once it enters central government (in the election immediately preceding entry into office, it is classified as a challenger party). Participation in a national war/crisis cabinets and national unity governments (e.g., Communists in France’s provisional government) does not in itself qualify a party as a dominant party. A dominant party will continue to be considered a dominant party after merging with a challenger party, but a party will be considered a challenger party if it splits from a dominant party. Using this definition, the following parties were challenger parties in Western Europe in the period under investigation (1950–2017). The parties that became dominant parties during the period are indicated with an asterisk. Last election in dataset Country Party Party name (as abbreviation challenger party) Austria ALÖ Alternative List Austria 1983 DU The Independents—Lugner’s List 1999 FPÖ Freedom Party of Austria 1983 * Fritz The Citizens’ Forum Austria 2008 Grüne The Greens—The Green Alternative 2017 LiF Liberal Forum 2008 Martin Hans-Peter Martin’s List 2006 Nein No—Citizens’ Initiative against -

Fianna Fáil: Past and Present

Fianna Fáil: Past and Present Alan Byrne Fianna Fáil were the dominant political prompted what is usually referred to as party in Ireland from their first term in gov- a civil-war but as Kieran Allen argues in ernment in the 1930s up until their disas- an earlier issue of this journal, the Free trous 2011 election. The party managed to State in effect mounted a successful counter- enjoy large support from the working class, revolution which was thoroughly opposed to as well as court close links with the rich- the working class movement.3 The defeat est people in Irish society. Often described signalled the end of the aspirations of the as more of a ‘national movement’ than a Irish revolution and the stagnation of the party, their popular support base has now state economically. Emigration was par- plummeted. As this article goes to print, ticularly high in this period, and the state the party (officially in opposition but en- was thoroughly conservative. The Catholic abling a Fine Gael government) is polling Church fostered strong links with Cumann at 26% approval.1 How did a party which na nGaedheal, often denouncing republicans emerged from the losing side of the civil war in its sermons. come to dominate Irish political life so thor- There were distinctive class elements to oughly? This article aims to trace the his- both the pro and anti-treaty sides. The tory of the party, analyse their unique brand Cumann na nGaedheal government drew its of populist politics as well as their relation- base from large farmers, who could rely on ship with Irish capitalism and the working exports to Britain.