Electoral Processes Report | SGI Sustainable Governance Indicators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DIE ERSTE Österreichische Spar-Casse Privatstiftung

DIE ERSTE österreichische Spar-Casse Privatstiftung Annual Report 2015 130 DIE ERSTE österreichische Spar-Casse Privatstiftung Annual Report 2015 Vienna, May 2016 CONTENT 2015: A YEAR WHEN CIVIL SOCIETY SHOWED WHAT IT IS CAPABLE OF 5 A CORE SHAREHOLDER PROVIDING A STABLE ENVIRONMENT 9 ERSTE FOUNDATION: THE MAIN SHAREHOLDER OF ERSTE GROUP 10 1995 – 2015: SREBRENICA TODAY 13 HIGHLIGHTS 25 CALENDAR 2015 49 OVERVIEW OF PROJECTS AND GRANTS 69 OVERVIEW OF FUNDING AND PROJECT EXPENSES BY PROGRAMME 91 ERSTE FOUNDATION LIBRARY 94 BOARDS AND TEAM 96 STATUS REPORT 99 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2015 107 Notes to Financial Statements 2015 113 Fixed Asset Register 2015 122 ASSOCIATION MEMBERS “DIE ERSTE ÖSTERREICHISCHE SPAR-CASSE PRIVATSTIFTUNG” 125 IMPRINT 128 4 2015: A year when civil society showed what it is capable of Our annual report 2015 – and this is certainly not an exaggeration – looks back on an exceptional year; it was exceptional for ERSTE Foundation and for the whole of Europe. On the Greek islands and along the Turkish coast, on the island of Lampedusa and on the high seas in the Mediterranean: for years there had been signs of what took Central and Northern Europe and the Balkans by such surprise in the summer of 2015 that the entire continent suddenly found itself in a kind of state of emergency. Hundreds of thousands of people fled the military conflicts in Syria and Iraq, the daily violence in Afghanistan and Pakistan; there were also quite a few people who escaped hunger and a lack of prospects in the refugee camps or countries without a functioning economy, be it in Africa or South- Eastern Europe. -

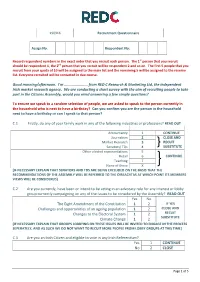

RED C Recruitment Questionnaire

190916 Recruitment Questionnaire Assign No. Respondent No: Record respondent numbers in the exact order that you recruit each person. The 1st person that you recruit should be respondent 1, the 2nd person that you recruit will be respondent 2 and so on. The first 5 people that you recruit from your quota of 10 will be assigned to the main list and the remaining 5 will be assigned to the reserve list. Everyone recruited will be contacted in due course. Good morning/afternoon. I'm ...................... from RED C Research & Marketing Ltd, the independent Irish market research agency. We are conducting a short survey with the aim of recruiting people to take part in the Citizens Assembly, would you mind answering a few simple questions? To ensure we speak to a random selection of people, we are asked to speak to the person currently in the household who is next to have a birthday? Can you confirm you are the person in the household next to have a birthday or can I speak to that person? C.1 Firstly, do any of your family work in any of the following industries or professions? READ OUT Accountancy 1 CONTINUE Journalism 2 CLOSE AND Market Research 3 RECUIT Senators/ TDs 4 SUBSTITUTE Other elected representatives 5 Retail 6 CONTINUE Teaching 7 None of these X [IF NECESSARY EXPLAIN THAT SENATORS AND TDS ARE BEING EXCLUDED ON THE BASIS THAT THE RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE ASSEMBLY WILL BE REFERRED TO THE OIREACHTAS AT WHICH POINT ITS MEMBERS VIEWS WILL BE CONSIDERED] C.2 Are you currently, have been or intend to be acting in an advocacy role for any -

The Remaking of the Dacian Identity in Romania and the Romanian Diaspora

THE REMAKING OF THE DACIAN IDENTITY IN ROMANIA AND THE ROMANIAN DIASPORA By Lucian Rosca A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Sociology Committee: ___________________________________________ Director ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Department Chairperson ___________________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: _____________________________________ Fall Semester 2015 George Mason University, Fairfax, VA The Remaking of the Dacian Identity in Romania and the Romanian Diaspora A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at George Mason University By Lucian I. Rosca Bachelor of Arts George Mason University, 2015 Director: Patricia Masters, Professor Department of Sociology Fall Semester 2015 George Mason University Fairfax, VA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis coordinators: Professor Patricia Masters, Professor Dae Young Kim, Professor Lester Kurtz, and my wife Paula, who were of invaluable help. Fi- nally, thanks go out to the Fenwick Library for providing a clean, quiet, and well- equipped repository in which to work. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Tables................................................................................................................... v List of Figures ............................................................................................................... -

Creating Community Over the Net: a Case Study of Romanian Online Journalism Mihaela V

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Creating Community over the Net: A Case Study of Romanian Online Journalism Mihaela V. Nocasian Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION CREATING COMMUNITY OVER THE NET: A CASE STUDY OF ROMANIAN ONLINE JOURNALISM By MIHAELA V. NOCASIAN A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2005 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Mihaela V. Nocasian defended on August 25, 2005. ________________________ Marilyn J. Young Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________ Gary Burnett Outside Committee Member ________________________ Davis Houck Committee Member ________________________ Andrew Opel Committee Member _________________________ Stephen D. McDowell Committee Member Approved: _____________________ Stephen D. McDowell, Chair, Department of Communication _____________________ John K. Mayo, Dean, College of Communication The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my mother, Anişoara, who taught me what it means to be compassionate. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The story of the Formula As community that I tell in this work would not have been possible without the support of those who believed in my abilities and offered me guidance, encouragement, and support. My committee members— Marilyn Young, Ph.D., Gary Burnett Ph.D., Stephen McDowell, Ph.D., Davis Houck, Ph.D., and Andrew Opel, Ph.D. — all offered valuable feedback during the various stages of completing this work. -

Notice-Of-Poll-Midla

IARRTHÓRA/CANDIDATE Moltóra/Proposer (if any) BRENNAN - SOLIDARITY PEOPLE BEFORE PROFIT (CYRIL BRENNAN of Rose Cottage, Lissacholly, Self Ballyshannon, Co. Donegal. Multi Task Attendant.) Liosta Ionaid SPBP Replacement List. CARTHY - SINN FÉIN Pearse Doherty (MATT CARTHY of 52 Foxfield, Carraig Mhachaire Rois, Magheraclogher, Derrybeg, Co. Mhuineacháin. Member of the European Parliament.) Letterkenny, Co. Donegal. Liosta Ionaid SF Replacement List. CASEY - NON PARTY (PETER CASEY of Edgewater House, Carrowhugh, Self Greencastle, Co. Donegal, F93 A2P3. Businessman) Liosta Ionaid PC Replacement List. FLANAGAN - NON-PARTY (LUKE 'MING' FLANAGAN of 5 Knockroe Park, Castlerea, Co. Roscommon. Full Time Public Self Representative.) Liosta Ionaid LMF Replacement List. GREENE - DIRECT DEMOCRACY IRELAND (D.D.I.) (PATRICK GREENE of Harestown Road, Brownstown, Self Monasterboice, Co. Louth. Timber Worker.) Liosta Ionaid DDI Replacement List. HANNIGAN - THE LABOUR PARTY (Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats) (DOMINIC HANNIGAN of 14B Glenview Self Drive, Galway, H91 Y5NA. Civil Engineer.) Liosta Ionaid LAB Replacement List. HEALY EAMES - NON-PARTY (FIDELMA HEALY EAMES of Maree, Oranmore, Self Co. Galway. Primary School Teacher.) Liosta Ionaid FHE Replacement List. MAHAPATRA - NON PARTY (DILIP MAHAPATRA of Elora, Stokeshill, Dromiskin, Self Dundalk, Co. Louth, A91 VW99. Medical Doctor.) McGUINNESS - FINE GAEL (Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats)) (MAIREAD McGUINNESS of Mentrim, Self Drumconrath, Navan, Co. Meath, C15 YE3H. Member of the European Parliament.) Liosta Ionaid FG Replacement List. McHUGH - GREEN PARTY/COMHAONTAS GLAS (SAOIRSE McHUGH of Dooagh, Achill, Co. Mayo. Self Sustainable Farming Advocate.) Liosta Ionaid GP Replacement List. MILLER - NON-PARTY (JAMES MILLER of Toorlisnamore, Kilbeggan, Self Co. Westmeath. -

Election Analysis and Prediction of Election Results with Twitter

DIPLOMA THESIS Election Analysis and Prediction of Election Results with Twitter Virginia Tsintzou Advisor: Associate Professor Panayiotis Tsaparas DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER SCIENCE & ENGINEERING UNIVERSITY OF IOANNINA October 2016 Acknowledgements First I would like to thank Professors Evaggelia Pitoura, Nikolaos Mamoulis for being members of my thesis committee and for their invaluable comments on my work and its perspectives. Special thanks to my advisor and also member of the committee Professor Panayiotis Tsaparas for his useful guidance and support. Most importantly, I have to acknowledge and thank him for his open mind to any ideas from his students and patience. Last but not least, I have to thank my parents Emilios and Nausika, my sister Iro, my friend Yiannos and all of my friends for their continuous support. i Table Of Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Motivation 1 1.2 Overview 2 1.3 Roadmap 3 2 Related Work 4 3 Data Collection 7 3.1 Ireland 7 3.1.1 Network 8 3.1.2 Tweets 10 3.2 United Kingdom 12 4 Algorithmic Techniques 13 4.1 Network 13 4.2 Tweets 18 5 Experimental Results 20 5.1 Ireland 20 5.1.1 Network 20 5.1.2 Tweets 26 5.2 United Kingdom 32 5.2.1 Tweets 32 6 Conclusions 34 7 References 35 Appendix i ii 1 Introduction 1.1 Motivation Elections are the means to people’s choice of representation. Due to their important role in politics, there always has been a big interest in predicting an election outcome. Lately, it is observed that traditional polls may fail to make an accurate prediction. -

Articol Oltean Romanian Migra

euro POLIS vol. 9, no.2/2015 ROMANIAN MIGRANTS’ POLITICAL TRANSNATIONALISM, ALTERNATIVE VOTING METHODS AND THEIR EFFECT ON THE ELECTORAL PROCESS Ovidiu Oltean Babeş-Bolyai University [email protected] Abstract The present paper continues this debate, discussing possible solutions and reforms that would improve external and out of country voting (OCV), and enhance and enable political participation and representation of the Romanian diaspora. Departing from the perspective of political transnationalism it reinforces the argument of extended citizenship rights for migrants, and analyzes the possibility of introduction of electronic or postal vote and the impact of such changes on the electoral process, drawing comparisons with states that already use similar voting systems. Keywords : internet voting, online voting, Estonia, diaspora. Presidential elections and voting problems in the diaspora The two rounds of presidential elections held in the autumn of 2014 will remain in the memory of many of us for their dramatic turning point and unexpected result. The discriminatory treatment and arrogant tone of the Romanian authorities and their lack of reaction to voters’ denied access to polling stations outside of country created much discontent at home and abroad. The Romanian electorate and civil society mobilized and sanctioned in return the government's mishandling and deliberate actions to influence the elections' outcome. Tens of thousands have taken it into the streets of the country’s largest cities to show solidarity with their co-nationals abroad who could not cast their votes for the election of a new president (Balkaninsight.com 2014), and created a big wave of support around the candidate running against the prime minister Victor Ponta. -

Ritual Year 8 Migrations

Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Studies with Ethnographic Museum at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences — SIEF Working Group on The Ritual Year Edited by Dobrinka Parusheva and Lina Gergova Sofia • 2014 THE RITUAL YEAR 8 MIGRATIONS The Yearbook of the SIEF Working Group on The Ritual Year Sofia, IEFSEM-BAS, 2014 Peer reviewed articles based on the presentations of the conference in Plovdiv, Bulgaria, 26-29 June 2012 General Editor: Emily Lyle Editors for this issue: Dobrinka Parusheva and Lina Gergova Language editors: Jenny Butler, Molly Carter, Cozette Griffin-Kremer, John Helsloot, Emily Lyle, Neill Martin, Nancy McEntire, David Stanley, Elizabeth Warner Design and layout: Yana Gergova Advisory board: Maria Teresa Agozzino, Marion Bowman, Jenny Butler, Molly Carter, Kinga Gáspár, Evy Håland, Aado Lintrop, Neill Martin, Lina Midholm, Tatiana Minniyakhmetova, David Stanley, Elizabeth Warner The Yearbook is established in 2011 by merging former periodicals dedicated to the study of the Ritual Year: Proceedings of the (5 volumes in 2005–2011). Published by the Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Studies with Ethnographic Museum at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences ISSN 2228-1347 © Authors © Dobrinka Parusheva & Lina Gergova, editors © Yana Gergova, design and layout © SIEF Working Group on The Ritual Year © IEFSEM-BAS CONTENTS Foreword 9 THE SEED-STORE OF THE YEAR Emily Lyle 15 MODERN SPORTS AWARDS CEREMONIES – A GENEALOGICAL ANALYSIS Grigor Har. Grigorov 27 THE RITUAL OF CHANGE IN A REMOTE AREA: CONTEMPORARY ARTS AND THE RENEWAL OF A -

DIRECT DEMOCRACY IRELAND a National Citizens Movement

DIRECT DEMOCRACY IRELAND A National Citizens Movement 2016 General Election Manifesto A New Democracy A Stronger Ireland Equality, Opportunity, Sustainability Table Of Contents Preface 1 Pat Greene 1 Alan Lawes 2 Introduction 3 Health 5 Education 8 Justice 11 Environment 15 Food, Farming, Agriculture and Fisheries 18 35 Point Manifesto 20 Closing Statement 33 Raymond Whitehead 33 Direct Democracy Ireland A National Citizens Movement Published by: Direct Democracy Ireland. Publication Date: Jan 2016 Contact Details: Direct Democracy Ireland The old post oce Reaghstown Ardee Co.Louth 0416855743 0894383597 [email protected] For further information Please visit www.DirectDemocracyIreland.ie Direct Democracy Ireland A National Citizens Movement Election Manifesto 2016 It is an honour and a privilege to lead Direct Democracy Ireland into the 2016 General Election, potentially the most important General Election in the history of this state. A role, I have accepted with humility, excitement and with a profound sense of duty. I joined Direct Democracy Ireland because of what I believed it can do for our country, and more than ever I believe that Direct Democracy provisions are the only future safeguards for Irish Citizens. We, in Direct Democracy Ireland have faced many challenges on our journey to date, but we all share a common vision for our country, and while we are all rm in our objectives, we will be exible in our approach so as to encourage the People of Ireland, individually and groups, our fellow political parties and others to strive to implement a policy of returning the provisions of Direct Democracy to our Nations Constitution. -

Dataset of Electoral Volatility in the European Parliament Elections Since 1979 Codebook (July 31, 2019)

Dataset of Electoral Volatility in the European Parliament elections since 1979 Vincenzo Emanuele (Luiss), Davide Angelucci (Luiss), Bruno Marino (Unitelma Sapienza), Leonardo Puleo (Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna), Federico Vegetti (University of Milan) Codebook (July 31, 2019) Description This dataset provides data on electoral volatility and its internal components in the elections for the European Parliament (EP) in all European Union (EU) countries since 1979 or the date of their accession to the Union. It also provides data about electoral volatility for both the class bloc and the demarcation bloc. This dataset will be regularly updated so as to include the next rounds of the European Parliament elections. Content Country: country where the EP election is held (in alphabetical order) Election_year: year in which the election is held Election_date: exact date of the election RegV: electoral volatility caused by vote switching between parties that enter or exit from the party system. A party is considered as entering the party system where it receives at least 1% of the national share in election at time t+1 (while it received less than 1% in election at time t). Conversely, a party is considered as exiting the part system where it receives less than 1% in election at time t+1 (while it received at least 1% in election at time t). AltV: electoral volatility caused by vote switching between existing parties, namely parties receiving at least 1% of the national share in both elections under scrutiny. OthV: electoral volatility caused by vote switching between parties falling below 1% of the national share in both the elections at time t and t+1. -

Register of Political Parties 17 February 2021

Na hAchtanna Toghcháin, 1992 go 2012 Electoral Acts, 1992 to 2012 (Section 25 of the Electoral Act, 1992 as substituted by Section 11 of the Electoral Act, 2001 and as amended by the Electoral (Amendment) Political Funding Act, 2012) _________________________________________ Clár na bPáirtithe Polaitíochta Register of Political Parties 17 February 2021 NAME OF PARTY EMBLEM ADDRESS OF PARTY NAME(S) OF OFFICER(S) AUTHORISED TO TYPES OF ELECTIONS/ EUROPEAN DETAILS OF HEADQUARTERS SIGN AUTHENTICATING CERTIFICATES PART OF THE STATE PARLIAMENT – ACCOUNTING OF CANDIDATES NAME OF UNITS AND POLITICAL RESPONSIBLE GROUP/EUROPEAN PERSONS POLITICAL PARTY Áras de Valera, Any one of the following persons:- Dáil Renew Europe, See Appendix 1 FIANNA FÁIL 65-66 Lower Mount Micheál Martin T.D. or European Alliance of Liberals Street, Margaret Conlon or Local and Democrats for Dublin 2. DO2 NX40 Seán Dorgan or Europe (ALDE) David Burke FINE GAEL 51 Upper Mount Any one of the following persons:- Dáil Group of the See Appendix 1 Street, Leo Varadkar T.D. European European People's Dublin 2. DO2 W924 Simon Coveney T.D. Local Party (Christian John Carroll Democrats) Terry Murphy THE LABOUR 2 White Friars Alan Kelly T.D. or Dáil Socialists and See Appendix 1 PARTY Aungier Street Billie Sparks European Democrats Group Dublin 2 D02 A008 Local THE WORKERS' 8 Cabra Road Any two of the following persons:- Dáil See Appendix 1 PARTY Dublin 7 James O’Brien European Seamus McDonagh Local Michael Donnelly Richard O’Hara COMMUNIST James Connolly Any one of the following persons:- Dáil PARTY OF IRELAND House, John Pinkerton European 43 East Essex Street, Eugene Mc Cartan Local Temple Bar, Dublin 2. -

An End to ``Civil War Politics

Electoral Studies 38 (2015) 71e81 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Electoral Studies journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/electstud An end to “Civil War politics”? The radically reshaped political landscape of post-crash Ireland * Adrian P. Kavanagh Maynooth University Department of Geography/National Institute for Regional and Spatial Analysis, National University of Ireland Maynooth, Co. Kildare, Ireland article info abstract Article history: The European debt crisis has impacted on electoral politics in most European states, but Received 27 June 2014 particularly in the Republic of Ireland. The severe nature of the economic crash and the Received in revised form 5 January 2015 subsequent application of austerity policies have brought large fluctuations in political Accepted 12 January 2015 support levels, with the three parties that have dominated the state since its foundation e Available online 21 January 2015 Fianna Fail, Fine Gael and Labour e all being adversely effected. The extent of these changes is highly controlled both by geography and by class, with political allegiances Keywords: proving to be highly fluid in certain parts of the state. Growing support levels for left wing Austerity Republic of Ireland parties and groupings, but most notably Sinn Fein, appear to be moving Irish politics away “ ” Civil War politics from the old Civil War style of politics and bringing it more into line with the traditional Class cleavage class cleavage politics of continental Europe. Electoral geography © 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. The economic “crash” of 2008 has resulted in a long suffered electoral setbacks in most European states during period of recession and austerity policies in the Republic this period (with the Christian Democrats in Germany of Ireland, which has had profound impacts for the Irish proving to be a notable exception), these trends has been political system as well as for economic and social life particularly evident in the more peripheral states within within the state.