Ek 1: Bursiyer Ve Programa Ait Bilgi Formu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

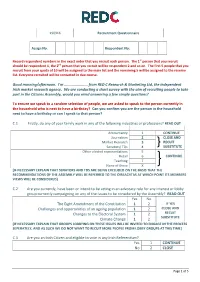

RED C Recruitment Questionnaire

190916 Recruitment Questionnaire Assign No. Respondent No: Record respondent numbers in the exact order that you recruit each person. The 1st person that you recruit should be respondent 1, the 2nd person that you recruit will be respondent 2 and so on. The first 5 people that you recruit from your quota of 10 will be assigned to the main list and the remaining 5 will be assigned to the reserve list. Everyone recruited will be contacted in due course. Good morning/afternoon. I'm ...................... from RED C Research & Marketing Ltd, the independent Irish market research agency. We are conducting a short survey with the aim of recruiting people to take part in the Citizens Assembly, would you mind answering a few simple questions? To ensure we speak to a random selection of people, we are asked to speak to the person currently in the household who is next to have a birthday? Can you confirm you are the person in the household next to have a birthday or can I speak to that person? C.1 Firstly, do any of your family work in any of the following industries or professions? READ OUT Accountancy 1 CONTINUE Journalism 2 CLOSE AND Market Research 3 RECUIT Senators/ TDs 4 SUBSTITUTE Other elected representatives 5 Retail 6 CONTINUE Teaching 7 None of these X [IF NECESSARY EXPLAIN THAT SENATORS AND TDS ARE BEING EXCLUDED ON THE BASIS THAT THE RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE ASSEMBLY WILL BE REFERRED TO THE OIREACHTAS AT WHICH POINT ITS MEMBERS VIEWS WILL BE CONSIDERED] C.2 Are you currently, have been or intend to be acting in an advocacy role for any -

Electoral Processes Report | SGI Sustainable Governance Indicators

Electoral Processes Report Candidacy Procedures, Media Access, Voting and Registration Rights, Party Financing, Popular Decision-Making m o c . e b o d a . k c Sustainable Governance o t s - e g Indicators 2018 e v © Sustainable Governance SGI Indicators SGI 2018 | 1 Electoral Processes Indicator Candidacy Procedures Question How fair are procedures for registering candidates and parties? 41 OECD and EU countries are sorted according to their performance on a scale from 10 (best) to 1 (lowest). This scale is tied to four qualitative evaluation levels. 10-9 = Legal regulations provide for a fair registration procedure for all elections; candidates and parties are not discriminated against. 8-6 = A few restrictions on election procedures discriminate against a small number of candidates and parties. 5-3 = Some unreasonable restrictions on election procedures exist that discriminate against many candidates and parties. 2-1 = Discriminating registration procedures for elections are widespread and prevent a large number of potential candidates or parties from participating. Australia Score 10 The Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) is an independent statutory authority that oversees the registration of candidates and parties according to the registration provisions of Part XI of the Commonwealth Electoral Act. The AEC is accountable for the conduct of elections to a cross-party parliamentary committee, the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters (JSCEM). JSCEM inquiries into and reports on any issues relating to electoral laws and practices and their administration. There are no significant barriers to registration for any potential candidate or party. A party requires a minimum of 500 members who are on the electoral roll. -

Information Guide Euroscepticism

Information Guide Euroscepticism A guide to information sources on Euroscepticism, with hyperlinks to further sources of information within European Sources Online and on external websites Contents Introduction .................................................................................................. 2 Brief Historical Overview................................................................................. 2 Euro Crisis 2008 ............................................................................................ 3 European Elections 2014 ................................................................................ 5 Euroscepticism in Europe ................................................................................ 8 Eurosceptic organisations ......................................................................... 10 Eurosceptic thinktanks ............................................................................. 10 Transnational Eurosceptic parties and political groups .................................. 11 Eurocritical media ................................................................................... 12 EU Reaction ................................................................................................. 13 Information sources in the ESO database ........................................................ 14 Further information sources on the internet ..................................................... 14 Copyright © 2016 Cardiff EDC. All rights reserved. 1 Cardiff EDC is part of the University Library -

Notice-Of-Poll-Midla

IARRTHÓRA/CANDIDATE Moltóra/Proposer (if any) BRENNAN - SOLIDARITY PEOPLE BEFORE PROFIT (CYRIL BRENNAN of Rose Cottage, Lissacholly, Self Ballyshannon, Co. Donegal. Multi Task Attendant.) Liosta Ionaid SPBP Replacement List. CARTHY - SINN FÉIN Pearse Doherty (MATT CARTHY of 52 Foxfield, Carraig Mhachaire Rois, Magheraclogher, Derrybeg, Co. Mhuineacháin. Member of the European Parliament.) Letterkenny, Co. Donegal. Liosta Ionaid SF Replacement List. CASEY - NON PARTY (PETER CASEY of Edgewater House, Carrowhugh, Self Greencastle, Co. Donegal, F93 A2P3. Businessman) Liosta Ionaid PC Replacement List. FLANAGAN - NON-PARTY (LUKE 'MING' FLANAGAN of 5 Knockroe Park, Castlerea, Co. Roscommon. Full Time Public Self Representative.) Liosta Ionaid LMF Replacement List. GREENE - DIRECT DEMOCRACY IRELAND (D.D.I.) (PATRICK GREENE of Harestown Road, Brownstown, Self Monasterboice, Co. Louth. Timber Worker.) Liosta Ionaid DDI Replacement List. HANNIGAN - THE LABOUR PARTY (Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats) (DOMINIC HANNIGAN of 14B Glenview Self Drive, Galway, H91 Y5NA. Civil Engineer.) Liosta Ionaid LAB Replacement List. HEALY EAMES - NON-PARTY (FIDELMA HEALY EAMES of Maree, Oranmore, Self Co. Galway. Primary School Teacher.) Liosta Ionaid FHE Replacement List. MAHAPATRA - NON PARTY (DILIP MAHAPATRA of Elora, Stokeshill, Dromiskin, Self Dundalk, Co. Louth, A91 VW99. Medical Doctor.) McGUINNESS - FINE GAEL (Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats)) (MAIREAD McGUINNESS of Mentrim, Self Drumconrath, Navan, Co. Meath, C15 YE3H. Member of the European Parliament.) Liosta Ionaid FG Replacement List. McHUGH - GREEN PARTY/COMHAONTAS GLAS (SAOIRSE McHUGH of Dooagh, Achill, Co. Mayo. Self Sustainable Farming Advocate.) Liosta Ionaid GP Replacement List. MILLER - NON-PARTY (JAMES MILLER of Toorlisnamore, Kilbeggan, Self Co. Westmeath. -

Election Analysis and Prediction of Election Results with Twitter

DIPLOMA THESIS Election Analysis and Prediction of Election Results with Twitter Virginia Tsintzou Advisor: Associate Professor Panayiotis Tsaparas DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER SCIENCE & ENGINEERING UNIVERSITY OF IOANNINA October 2016 Acknowledgements First I would like to thank Professors Evaggelia Pitoura, Nikolaos Mamoulis for being members of my thesis committee and for their invaluable comments on my work and its perspectives. Special thanks to my advisor and also member of the committee Professor Panayiotis Tsaparas for his useful guidance and support. Most importantly, I have to acknowledge and thank him for his open mind to any ideas from his students and patience. Last but not least, I have to thank my parents Emilios and Nausika, my sister Iro, my friend Yiannos and all of my friends for their continuous support. i Table Of Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Motivation 1 1.2 Overview 2 1.3 Roadmap 3 2 Related Work 4 3 Data Collection 7 3.1 Ireland 7 3.1.1 Network 8 3.1.2 Tweets 10 3.2 United Kingdom 12 4 Algorithmic Techniques 13 4.1 Network 13 4.2 Tweets 18 5 Experimental Results 20 5.1 Ireland 20 5.1.1 Network 20 5.1.2 Tweets 26 5.2 United Kingdom 32 5.2.1 Tweets 32 6 Conclusions 34 7 References 35 Appendix i ii 1 Introduction 1.1 Motivation Elections are the means to people’s choice of representation. Due to their important role in politics, there always has been a big interest in predicting an election outcome. Lately, it is observed that traditional polls may fail to make an accurate prediction. -

DIRECT DEMOCRACY IRELAND a National Citizens Movement

DIRECT DEMOCRACY IRELAND A National Citizens Movement 2016 General Election Manifesto A New Democracy A Stronger Ireland Equality, Opportunity, Sustainability Table Of Contents Preface 1 Pat Greene 1 Alan Lawes 2 Introduction 3 Health 5 Education 8 Justice 11 Environment 15 Food, Farming, Agriculture and Fisheries 18 35 Point Manifesto 20 Closing Statement 33 Raymond Whitehead 33 Direct Democracy Ireland A National Citizens Movement Published by: Direct Democracy Ireland. Publication Date: Jan 2016 Contact Details: Direct Democracy Ireland The old post oce Reaghstown Ardee Co.Louth 0416855743 0894383597 [email protected] For further information Please visit www.DirectDemocracyIreland.ie Direct Democracy Ireland A National Citizens Movement Election Manifesto 2016 It is an honour and a privilege to lead Direct Democracy Ireland into the 2016 General Election, potentially the most important General Election in the history of this state. A role, I have accepted with humility, excitement and with a profound sense of duty. I joined Direct Democracy Ireland because of what I believed it can do for our country, and more than ever I believe that Direct Democracy provisions are the only future safeguards for Irish Citizens. We, in Direct Democracy Ireland have faced many challenges on our journey to date, but we all share a common vision for our country, and while we are all rm in our objectives, we will be exible in our approach so as to encourage the People of Ireland, individually and groups, our fellow political parties and others to strive to implement a policy of returning the provisions of Direct Democracy to our Nations Constitution. -

Dataset of Electoral Volatility in the European Parliament Elections Since 1979 Codebook (July 31, 2019)

Dataset of Electoral Volatility in the European Parliament elections since 1979 Vincenzo Emanuele (Luiss), Davide Angelucci (Luiss), Bruno Marino (Unitelma Sapienza), Leonardo Puleo (Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna), Federico Vegetti (University of Milan) Codebook (July 31, 2019) Description This dataset provides data on electoral volatility and its internal components in the elections for the European Parliament (EP) in all European Union (EU) countries since 1979 or the date of their accession to the Union. It also provides data about electoral volatility for both the class bloc and the demarcation bloc. This dataset will be regularly updated so as to include the next rounds of the European Parliament elections. Content Country: country where the EP election is held (in alphabetical order) Election_year: year in which the election is held Election_date: exact date of the election RegV: electoral volatility caused by vote switching between parties that enter or exit from the party system. A party is considered as entering the party system where it receives at least 1% of the national share in election at time t+1 (while it received less than 1% in election at time t). Conversely, a party is considered as exiting the part system where it receives less than 1% in election at time t+1 (while it received at least 1% in election at time t). AltV: electoral volatility caused by vote switching between existing parties, namely parties receiving at least 1% of the national share in both elections under scrutiny. OthV: electoral volatility caused by vote switching between parties falling below 1% of the national share in both the elections at time t and t+1. -

Register of Political Parties 17 February 2021

Na hAchtanna Toghcháin, 1992 go 2012 Electoral Acts, 1992 to 2012 (Section 25 of the Electoral Act, 1992 as substituted by Section 11 of the Electoral Act, 2001 and as amended by the Electoral (Amendment) Political Funding Act, 2012) _________________________________________ Clár na bPáirtithe Polaitíochta Register of Political Parties 17 February 2021 NAME OF PARTY EMBLEM ADDRESS OF PARTY NAME(S) OF OFFICER(S) AUTHORISED TO TYPES OF ELECTIONS/ EUROPEAN DETAILS OF HEADQUARTERS SIGN AUTHENTICATING CERTIFICATES PART OF THE STATE PARLIAMENT – ACCOUNTING OF CANDIDATES NAME OF UNITS AND POLITICAL RESPONSIBLE GROUP/EUROPEAN PERSONS POLITICAL PARTY Áras de Valera, Any one of the following persons:- Dáil Renew Europe, See Appendix 1 FIANNA FÁIL 65-66 Lower Mount Micheál Martin T.D. or European Alliance of Liberals Street, Margaret Conlon or Local and Democrats for Dublin 2. DO2 NX40 Seán Dorgan or Europe (ALDE) David Burke FINE GAEL 51 Upper Mount Any one of the following persons:- Dáil Group of the See Appendix 1 Street, Leo Varadkar T.D. European European People's Dublin 2. DO2 W924 Simon Coveney T.D. Local Party (Christian John Carroll Democrats) Terry Murphy THE LABOUR 2 White Friars Alan Kelly T.D. or Dáil Socialists and See Appendix 1 PARTY Aungier Street Billie Sparks European Democrats Group Dublin 2 D02 A008 Local THE WORKERS' 8 Cabra Road Any two of the following persons:- Dáil See Appendix 1 PARTY Dublin 7 James O’Brien European Seamus McDonagh Local Michael Donnelly Richard O’Hara COMMUNIST James Connolly Any one of the following persons:- Dáil PARTY OF IRELAND House, John Pinkerton European 43 East Essex Street, Eugene Mc Cartan Local Temple Bar, Dublin 2. -

An End to ``Civil War Politics

Electoral Studies 38 (2015) 71e81 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Electoral Studies journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/electstud An end to “Civil War politics”? The radically reshaped political landscape of post-crash Ireland * Adrian P. Kavanagh Maynooth University Department of Geography/National Institute for Regional and Spatial Analysis, National University of Ireland Maynooth, Co. Kildare, Ireland article info abstract Article history: The European debt crisis has impacted on electoral politics in most European states, but Received 27 June 2014 particularly in the Republic of Ireland. The severe nature of the economic crash and the Received in revised form 5 January 2015 subsequent application of austerity policies have brought large fluctuations in political Accepted 12 January 2015 support levels, with the three parties that have dominated the state since its foundation e Available online 21 January 2015 Fianna Fail, Fine Gael and Labour e all being adversely effected. The extent of these changes is highly controlled both by geography and by class, with political allegiances Keywords: proving to be highly fluid in certain parts of the state. Growing support levels for left wing Austerity Republic of Ireland parties and groupings, but most notably Sinn Fein, appear to be moving Irish politics away “ ” Civil War politics from the old Civil War style of politics and bringing it more into line with the traditional Class cleavage class cleavage politics of continental Europe. Electoral geography © 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. The economic “crash” of 2008 has resulted in a long suffered electoral setbacks in most European states during period of recession and austerity policies in the Republic this period (with the Christian Democrats in Germany of Ireland, which has had profound impacts for the Irish proving to be a notable exception), these trends has been political system as well as for economic and social life particularly evident in the more peripheral states within within the state. -

2015 and the Related Statements of Income, Retained Earnings, and Cash Flows for the Year Then Ended, and the Related Notes to the Financial Statements

Independent Auditors' Report To: Patrick Walsh, Commission Secretary, Standards in Public Office Cormnission, 18 Lower Leeson Street, Dublin 2 & The Members of Direct Democracy Ireland. Report on the Financial Statements We have audited the accompanying balance sheet of Direct Democracy Ireland as of 31st December 2015 and the related statements of income, retained earnings, and cash flows for the year then ended, and the related notes to the financial statements. Management's Responsibility for the Financial Statements Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of these financial statements in accordance with accounting principles generally accepted in the Republic of Ireland; this includes the design, implementation, and maintenance of internal control relevant to the preparation and fair presentation of consolidated financial statements that are free from material rnisstatement, whether due to fraud or error. Auditor's Responsibility Our responsibility is to express an opinion on these financial statements based on our audit. We conducted our audits in accordance with auditing standards generauy accepted in the ReptibhC. OE Srelan&. TllOSe Staildaras reqlllre tn' a 'We pian aIla pertorrn he audIt [0 0btaln reasonable assurance about whether the financial statements are free of material misstatement. An audit involves perforrning procedures to obtain audit evidence about the amounts and the disclosures in the financial statements. The procedures selected depend on the auditor's judgement, including the assessment of the risks of material rnisstatement of the financial statements, whether due to fraud or error. In making those risk assessments, the auditor considers internal control relevant to the entity's preparation and fair presentation of the financial statements in order to design audit procedures that are appropriate in the circurnstances, but not for the purpose of expressing an opinion on the effectiveness of the entity's internal control. -

7. Austerity, Resistance and Social Protest in Ireland: Movement Outcomes

7. Austerity, resistance and social protest in Ireland: movement outcomes Niamh Hourigan Introduction The varying protest responses of European societies to structural adjustment programmes imposed by the European Union/European Central Bank/International Monetary Fund after the 2008 banking crisis have been one of the most intriguing sociological dimensions of the recent global economic recession. During the early years of the crisis, Ireland and Greece were often portrayed in the international media at opposing ends of a spectrum of protest, with Ireland indeed politically positioning itself in this way (Borooah 2014). The Greeks were characterised as taking to the streets in significant numbers to protest against austerity while Irish citizens meekly accepted their fate. Detailed research on protest in each context demonstrates that this contrast has been overdrawn (Pappas and O’Malley 2014; Power et al. 2015; Karyotis and Rudig 2015; Hearne 2015). However, a number of distinctive features of the Irish protest response to austerity merit critical consideration. This chapter begins by mapping the four overlapping phases of Irish anti-austerity protest between 2008 and 2016, which can be 115 TEXT TO PRINT.indd 115 8/10/2017 10:48:22 AM characterised as (1) early single-issue protests, (2) muted protest, (3) popular mobilisation, (4) deepening confrontation leading to political realignment. The achievements of the Irish anti-austerity movement are considered in light of research on social movement outcomes (Gamson 1975; Giugni et al. 1999; Amenta et al. 2010). Within this literature, the successes and failures of social movements are examined in terms of three key criteria: goal attainment, changes to systems of interest representation, and value transformation. -

The State of Populism in Europe (2016)

2016 THE STATE OF POPULISM IN EUROPE Tamás BOROS Maria FREITAS Tibor KADLT Ernst STETTER The State of Populism in the European Union 2016 Published by: FEPS – Foundaton for European Progressive Studies Rue Montoyer, 40 – 1000 Brussels, Belgium www.feps-europe.eu Policy Solutons Square Ambiorix, 10 – 1000 Brussels, Belgium Revay utca, 10 – 1065 Budapest, Hungary www.policysolutons.eu Responsible editors: Ernst Steter, Tamás Boros Edited by: Maria Freitas Cover design: Ferling Ltd. – Hungary Page layout and printng: Ferling Ltd. – Hungary, Innovariant Ltd. Copyrights: FEPS, Policy Solutons ISSN: ISSN 2498-5147 This book is produced with the fnancial support of the European Parliament. Table of Contents Foreword 6 About Populism Tracker 8 Methodology 9 Overview: The most important trends in the support for populism in 2016 10 Countries with high support for populists 10 Most successful populist partes 14 Populists in government 18 Populist partes in EU Member States 21 Western Europe 21 Central and eastern Europe 24 Southern Europe 28 Northern Europe 31 Conclusion 34 Appendix I. Chronology: European populism in 2016 37 Appendix II. List of populist partes in the European Union 43 Foreword 2016 has been one of the most eventul years in European politcs since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Observers accustomed to predictable European afairs were shocked again and again by unexpected events: the refugee crisis – stll lingering from the previous year – and the social tensions surrounding it; the Britsh referendum on leaving the European Union (EU) and its striking outcome that shook the European project to its core with the unprecedented case of a Member State partng from the EU; the surprising results of German regional electons and the worrying trend of increasing popularity of right wing populists; the Hungarian plebiscite on the EU’s migrant quota, which added to refugee crisis tensions at the European level; and the Italian referendum on consttutonal reforms that turned into a protest vote against the country’s prime minister.