7. Austerity, Resistance and Social Protest in Ireland: Movement Outcomes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dáil Éireann

Vol. 960 Wednesday, No. 5 18 October 2017 DÍOSPÓIREACHTAÍ PARLAIMINTE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DÁIL ÉIREANN TUAIRISC OIFIGIÚIL—Neamhcheartaithe (OFFICIAL REPORT—Unrevised) Insert Date Here 18/10/2017A00100Water Services Bill 2017: Second Stage (Resumed) � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 493 18/10/2017E00400Legal Metrology (Measuring Instruments) Bill 2017: Order for Report Stage� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 501 18/10/2017E00700Legal Metrology (Measuring Instruments) Bill 2017: Report and Final Stages � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 501 18/10/2017F00100Criminal Justice (Victims of Crime) Bill 2016: From the Seanad � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 502 18/10/2017K00100Leaders’ Questions � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 513 18/10/2017O00600Questions on Promised Legislation � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 523 18/10/2017S00950Departmental Communications � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 535 18/10/2017T01150Cabinet Committee Meetings � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 539 18/10/2017V00650EU Summits � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 543 18/10/2017GG00200Topical -

Brochure: Ireland's Meps 2019-2024 (EN) (Pdf 2341KB)

Clare Daly Deirdre Clune Luke Ming Flanagan Frances Fitzgerald Chris MacManus Seán Kelly Mick Wallace Colm Markey NON-ALIGNED Maria Walsh 27MEPs 40MEPs 18MEPs7 62MEPs 70MEPs5 76MEPs 14MEPs8 67MEPs 97MEPs Ciarán Cuffe Barry Andrews Grace O’Sullivan Billy Kelleher HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH Printed in November 2020 in November Printed MIDLANDS-NORTH-WEST DUBLIN SOUTH Luke Ming Flanagan Chris MacManus Colm Markey Group of the European United Left - Group of the European United Left - Group of the European People’s Nordic Green Left Nordic Green Left Party (Christian Democrats) National party: Sinn Féin National party: Independent Nat ional party: Fine Gael COMMITTEES: COMMITTEES: COMMITTEES: • Budgetary Control • Agriculture and Rural Development • Agriculture and Rural Development • Agriculture and Rural Development • Economic and Monetary Affairs (substitute member) • Transport and Tourism Midlands - North - West West Midlands - North - • International Trade (substitute member) • Fisheries (substitute member) Barry Andrews Ciarán Cuffe Clare Daly Renew Europe Group Group of the Greens / Group of the European United Left - National party: Fianna Fáil European Free Alliance Nordic Green Left National party: Green Party National party: Independents Dublin COMMITTEES: COMMITTEES: COMMITTEES: for change • International Trade • Industry, Research and Energy • Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs • Development (substitute member) • Transport and Tourism • International Trade (substitute member) • Foreign Interference in all Democratic • -

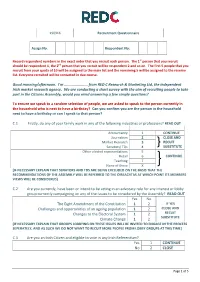

RED C Recruitment Questionnaire

190916 Recruitment Questionnaire Assign No. Respondent No: Record respondent numbers in the exact order that you recruit each person. The 1st person that you recruit should be respondent 1, the 2nd person that you recruit will be respondent 2 and so on. The first 5 people that you recruit from your quota of 10 will be assigned to the main list and the remaining 5 will be assigned to the reserve list. Everyone recruited will be contacted in due course. Good morning/afternoon. I'm ...................... from RED C Research & Marketing Ltd, the independent Irish market research agency. We are conducting a short survey with the aim of recruiting people to take part in the Citizens Assembly, would you mind answering a few simple questions? To ensure we speak to a random selection of people, we are asked to speak to the person currently in the household who is next to have a birthday? Can you confirm you are the person in the household next to have a birthday or can I speak to that person? C.1 Firstly, do any of your family work in any of the following industries or professions? READ OUT Accountancy 1 CONTINUE Journalism 2 CLOSE AND Market Research 3 RECUIT Senators/ TDs 4 SUBSTITUTE Other elected representatives 5 Retail 6 CONTINUE Teaching 7 None of these X [IF NECESSARY EXPLAIN THAT SENATORS AND TDS ARE BEING EXCLUDED ON THE BASIS THAT THE RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE ASSEMBLY WILL BE REFERRED TO THE OIREACHTAS AT WHICH POINT ITS MEMBERS VIEWS WILL BE CONSIDERED] C.2 Are you currently, have been or intend to be acting in an advocacy role for any -

European Parliament Elections 2019 - Forecast

Briefing May 2019 European Parliament Elections 2019 - Forecast Austria – 18 MEPs Staff lead: Nick Dornheim PARTIES (EP group) Freedom Party of Austria The Greens – The Green Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) (EPP) Social Democratic Party of Austria NEOS – The New (FPÖ) (Salvini’s Alliance) – Alternative (Greens/EFA) – 6 seats (SPÖ) (S&D) - 5 seats Austria (ALDE) 1 seat 5 seats 1 seat 1. Othmar Karas* Andreas Schieder Harald Vilimsky* Werner Kogler Claudia Gamon 2. Karoline Edtstadler Evelyn Regner* Georg Mayer* Sarah Wiener Karin Feldinger 3. Angelika Winzig Günther Sidl Petra Steger Monika Vana* Stefan Windberger 4. Simone Schmiedtbauer Bettina Vollath Roman Haider Thomas Waitz* Stefan Zotti 5. Lukas Mandl* Hannes Heide Vesna Schuster Olga Voglauer Nini Tsiklauri 6. Wolfram Pirchner Julia Elisabeth Herr Elisabeth Dieringer-Granza Thomas Schobesberger Johannes Margreiter 7. Christian Sagartz Christian Alexander Dax Josef Graf Teresa Reiter 8. Barbara Thaler Stefanie Mösl Maximilian Kurz Isak Schneider 9. Christian Zoll Luca Peter Marco Kaiser Andrea Kerbleder Peter Berry 10. Claudia Wolf-Schöffmann Theresa Muigg Karin Berger Julia Reichenhauser NB 1: Only the parties reaching the 4% electoral threshold are mentioned in the table. Likely to be elected Unlikely to be elected or *: Incumbent Member of the NB 2: 18 seats are allocated to Austria, same as in the previous election. and/or take seat to take seat, if elected European Parliament ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• www.eurocommerce.eu Belgium – 21 MEPs Staff lead: Stefania Moise PARTIES (EP group) DUTCH SPEAKING CONSITUENCY FRENCH SPEAKING CONSITUENCY GERMAN SPEAKING CONSTITUENCY 1. Geert Bourgeois 1. Paul Magnette 1. Pascal Arimont* 2. Assita Kanko 2. Maria Arena* 2. -

Hon. Mr President of the European Parliament, Dear David Sassoli

Hon. Mr President of the European Parliament, Dear David Sassoli, Since March, when the outbreak of COVID-19 intensified in Europe, the functioning of the European Parliament (EP) has changed dramatically, due to the sanitary measures applied. We understand the inevitability of the contingency plan, taking into account the need to prevent infection and the spread of the virus and to protect the health and lives of people. Six months later, the functioning of the EP is gradually returning to normal. However, there are services whose unavailability seriously impairs parliamentary work, namely the interpretation service. The European Union (EU) has 24 official languages and all deserve the same respect and treatment. We recognize that the number of languages available in committee meeting rooms has been increasing, but even so, more than half of the languages still have no interpretation. Multilingualism is a right enshrined in the Treaties that allows Members to express themselves in their own language. Now, that is not happening and we are concerned that the situation will continue, even taking into account the expected workflow in the commissions after these atypical six months. In this sense, we appeal, once again, to you, the President of the EP for the application of the letter and the spirit of the principle of multilingualism, finding solutions that respect this principle and that allow the use of any of the 24 official languages of the EU. The expression of each deputy in her/his own language is a priority so that there can be conditions to fully exercise the mandate for which she/he was elected and a condition of respect for the citizens who elected her/him. -

Electoral Processes Report | SGI Sustainable Governance Indicators

Electoral Processes Report Candidacy Procedures, Media Access, Voting and Registration Rights, Party Financing, Popular Decision-Making m o c . e b o d a . k c Sustainable Governance o t s - e g Indicators 2018 e v © Sustainable Governance SGI Indicators SGI 2018 | 1 Electoral Processes Indicator Candidacy Procedures Question How fair are procedures for registering candidates and parties? 41 OECD and EU countries are sorted according to their performance on a scale from 10 (best) to 1 (lowest). This scale is tied to four qualitative evaluation levels. 10-9 = Legal regulations provide for a fair registration procedure for all elections; candidates and parties are not discriminated against. 8-6 = A few restrictions on election procedures discriminate against a small number of candidates and parties. 5-3 = Some unreasonable restrictions on election procedures exist that discriminate against many candidates and parties. 2-1 = Discriminating registration procedures for elections are widespread and prevent a large number of potential candidates or parties from participating. Australia Score 10 The Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) is an independent statutory authority that oversees the registration of candidates and parties according to the registration provisions of Part XI of the Commonwealth Electoral Act. The AEC is accountable for the conduct of elections to a cross-party parliamentary committee, the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters (JSCEM). JSCEM inquiries into and reports on any issues relating to electoral laws and practices and their administration. There are no significant barriers to registration for any potential candidate or party. A party requires a minimum of 500 members who are on the electoral roll. -

The Eurozone Banking Crisis

THE EUROZONE BANKING CRISIS DID THE ECB AND THE BANKS COLLUDE TO HIDE LOSSES, THUS DISTORTING THEIR OWN BALANCE SHEETS? By CORMAC BUTLER and ED HEAPHY Commissioned by Luke Ming Flanagan MEP 1 Table of Contents 2 FOREWORD by Luke Ming Flanagan MEP ................................................................... 1 2.1 New currency launched – already holed below the water-line..............................................1 2.2 The ECB ...................................................................................................................................1 2.3 Heaphy and Butler – posing pertinent questions ...................................................................1 2.4 EXTRACT FROM PAUL DE GRAUWE FINANCIAL TIMES ARTICLE – 20/02/1998:.....................2 3 BIOGRAPHIES ............................................................................................................ 3 3.1 Cormac Butler .........................................................................................................................3 3.2 Ed Heaphy ...............................................................................................................................4 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................... 5 4.1 IAS 39 makes its appearance ..................................................................................................6 4.2 Cause and Consequence .........................................................................................................7 -

Annual Activity Report 2020 European Parliament Liaison Office in Ireland Europe House 12-14 Lower Mount Street Dublin D02 W710 Tel

The European Parliament Liaison Office in Ireland Annual activity report 2020 European Parliament Liaison Office in Ireland Europe House 12-14 Lower Mount Street Dublin D02 W710 Tel. +353 (0)1 6057900 Website: www.europarl.ie Facebook: @EPinIreland Twitter: @EPinIreland and @EPIreland_Edu Instagram: @ep_ireland © European Union/EP, 2021 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Contents Contents 3 Top Posts and Tweets in 2020 34 Top Content Highlighting MEPs’ Work 36 Introduction 5 Top Content on Cooperation with other Members of the Organisations and MEPs 39 European Parliament for Ireland 6 Top Content Produced by EPLO Dublin 40 Remote Plenary Sessions 7 Strategy 41 Social Media Data Overview 41 Outreach Activities 10 Cross-border activities 13 Activities for young people 42 Regular newsletter 17 European Parliament Ambassador School Campaigns 18 Programme (EPAS) 42 International Women’s Day 18 Euroscola 44 Charlemagne Youth Prize 19 Information visits to Europe House Europeans Against COVID-19 19 in Dublin 45 European Citizen’s Prize 21 Blue Star Programme 45 Lux Audience Award 21 Other youth activities 46 Sakharov Prize 21 Back to school 47 Bridge the Pond initiative 48 Other information activities 22 Annexes 43 EP grant programme Annex I - Ambassador Schools for information activities 24 Academic Year 2019-2020 49 Media 25 Annex II - Ambassador Schools Journalism students and the EP 25 Academic Year 2020-2021 50 Europeans Against COVID-19 26 Annex III - Schools representing Ireland at Commission hearings and -

Brussels, 24 February 2021

Brussels, 24 February 2021 Declaration from Members of the European Parliament to urge the Commission and Member States not to block the TRIPS waiver at the WTO and to support global access to COVID-19 vaccines We, Members of the European Parliament, urge the European Commission and the European Council to review their opposition to the TRIPS waiver proposal at the World Trade Organisation (WTO), which serves to enable greater access to affordable COVID-19 health technologies, including vaccines, in particular for developing and middle income countries. This call comes in view of the European Council meeting of 25 February 2021 and the crucial decision to be made by all Member States at the WTO General Council on 1-2 March 2021. Since the beginning of the pandemic, the need to ensure global open access to COVID-19 health technologies and to rapidly scale up their manufacturing and supply has been widely acknowledged. However, despite efforts and statements made by the European Commission and several heads of state in support of treating COVID-19 medical products as global public goods, this has not yet translated into actionable realities. In this context, the EU’s open opposition to the TRIPS waiver risks exacerbating a dangerous North-South divide when it comes to affordable access to COVID-19 diagnostics, personal protective equipment, treatments and vaccines. The WTO decision on a potential waiver offers a crucial and much-needed act of effective solidarity, as it is an important step towards increasing local production in partner countries and, ultimately, suppressing this pandemic on a global scale. -

Notice-Of-Poll-Midla

IARRTHÓRA/CANDIDATE Moltóra/Proposer (if any) BRENNAN - SOLIDARITY PEOPLE BEFORE PROFIT (CYRIL BRENNAN of Rose Cottage, Lissacholly, Self Ballyshannon, Co. Donegal. Multi Task Attendant.) Liosta Ionaid SPBP Replacement List. CARTHY - SINN FÉIN Pearse Doherty (MATT CARTHY of 52 Foxfield, Carraig Mhachaire Rois, Magheraclogher, Derrybeg, Co. Mhuineacháin. Member of the European Parliament.) Letterkenny, Co. Donegal. Liosta Ionaid SF Replacement List. CASEY - NON PARTY (PETER CASEY of Edgewater House, Carrowhugh, Self Greencastle, Co. Donegal, F93 A2P3. Businessman) Liosta Ionaid PC Replacement List. FLANAGAN - NON-PARTY (LUKE 'MING' FLANAGAN of 5 Knockroe Park, Castlerea, Co. Roscommon. Full Time Public Self Representative.) Liosta Ionaid LMF Replacement List. GREENE - DIRECT DEMOCRACY IRELAND (D.D.I.) (PATRICK GREENE of Harestown Road, Brownstown, Self Monasterboice, Co. Louth. Timber Worker.) Liosta Ionaid DDI Replacement List. HANNIGAN - THE LABOUR PARTY (Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats) (DOMINIC HANNIGAN of 14B Glenview Self Drive, Galway, H91 Y5NA. Civil Engineer.) Liosta Ionaid LAB Replacement List. HEALY EAMES - NON-PARTY (FIDELMA HEALY EAMES of Maree, Oranmore, Self Co. Galway. Primary School Teacher.) Liosta Ionaid FHE Replacement List. MAHAPATRA - NON PARTY (DILIP MAHAPATRA of Elora, Stokeshill, Dromiskin, Self Dundalk, Co. Louth, A91 VW99. Medical Doctor.) McGUINNESS - FINE GAEL (Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats)) (MAIREAD McGUINNESS of Mentrim, Self Drumconrath, Navan, Co. Meath, C15 YE3H. Member of the European Parliament.) Liosta Ionaid FG Replacement List. McHUGH - GREEN PARTY/COMHAONTAS GLAS (SAOIRSE McHUGH of Dooagh, Achill, Co. Mayo. Self Sustainable Farming Advocate.) Liosta Ionaid GP Replacement List. MILLER - NON-PARTY (JAMES MILLER of Toorlisnamore, Kilbeggan, Self Co. Westmeath. -

Christine Marking-Andriessen

‘Developing a Call to Action on unmet needs in PKU’ 1 ‘Developing a Call to Action on unmet needs in PKU’ EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MEETING OBJECTIVES: • To critically reflect on, discuss, and provide feedback on a draft Call to Action on unmet needs in PKU • To explore the best ways of making use of such a Call to Action UNMET NEEDS AND REQUIRED ACTIONS ADDRESSED: • Acknowledge PKU as a life-long disorder • Take account of the neurological and mental health impact of PKU • Make new-born screening a reality across Europe • Support the implementation of good practice in PKU treatment: European guidelines • Ensure access and adherence to appropriate dietary therapy • Establish clear and consistent protein food labelling • Facilitate access to innovative treatment MAIN CONCLUSIONS • Agreement on the identified unmet needs • Strong support for a Call to Action • Agreement on making use of the Call to Action as an advocacy tool to raise awareness of unmet needs in PKU as well as of the activities of the EP Cross-Party Alliance on PKU • During 2021, concerted efforts will be made to broaden the support base for the Cross- Party Alliance in the European Parliament and beyond 2 ‘Developing a Call to Action on unmet needs in PKU’ MEETING REPORT _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WELCOME AND INTRODUCTIONS Sue Saville (former Medical Correspondent at ITV News, UK) welcomed delegates from the European Society for Phenylketonuria and Allied Disorders Treated as Phenylketonuria (ESPKU) and MEPs and underlined the aim of the meeting, i.e., to build consensus on the most important and compelling actions that could be taken, at both national and EU level, to address the unmet needs in PKU. -

University of Dundee Beyond Nationalism? the Anti-Austerity

University of Dundee Beyond Nationalism? The Anti-Austerity Social Movement in Ireland Dunphy, Richard Published in: Journal of Civil Society DOI: 10.1080/17448689.2017.1355031 Publication date: 2017 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication in Discovery Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Dunphy, R. (2017). Beyond Nationalism? The Anti-Austerity Social Movement in Ireland: Between Domestic Constraints and Lessons from Abroad. Journal of Civil Society, 13(3), 267-283. https://doi.org/10.1080/17448689.2017.1355031 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in Discovery Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from Discovery Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Apr. 2019 Journal of Civil Society For Peer Review Only Beyond nationalism? The Anti-Austerity Social Movement in Ireland: Between Domestic Constraints and Lessons from Abroad