The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Killiecrankie Designation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Soldier Fights for Three Separate but Sometimes Associated Reasons: for Duty, for Payment and for Cause

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stirling Online Research Repository The press and military conflict in early modern Scotland by Alastair J. Mann A soldier fights for three separate but sometimes associated reasons: for duty, for payment and for cause. Nathianiel Hawthorne once said of valour, however, that ‘he is only brave who has affections to fight for’. Those soldiers who are prepared most readily to risk their lives are those driven by political and religious passions. From the advent of printing to the present day the printed word has provided governments and generals with a means to galvanise support and to delineate both the emotional and rational reasons for participation in conflict. Like steel and gunpowder, the press was generally available to all military propagandists in early modern Europe, and so a press war was characteristic of outbreaks of civil war and inter-national war, and thus it was for those conflicts involving the Scottish soldier. Did Scotland’s early modern soldiers carry print into battle? Paul Huhnerfeld, the biographer of the German philosopher and Nazi Martin Heidegger, provides the curious revelation that German soldiers who died at the Russian front in the Second World War were to be found with copies of Heidegger’s popular philosophical works, with all their nihilism and anti-Semitism, in their knapsacks.1 The evidence for such proximity between print and combat is inconclusive for early modern Scotland, at least in any large scale. Officers and military chaplains certainly obtained religious pamphlets during the covenanting period from 1638 to 1651. -

The Post Office Perth Directory

i y^ ^'^•\Hl,(a m \Wi\ GOLD AND SILVER SMITH, 31 SIIG-S: STI^EET. PERTH. SILVER TEA AND COFFEE SERVICES, BEST SHEFFIELD AND BIRMINGHAM (!^lettro-P:a3tteto piateb Crutt mb spirit /tamtjs, ^EEAD BASKETS, WAITEKS, ^NS, FORKS, FISH CARVERS, ci &c. &c. &c. ^cotct) pearl, pebble, arib (STatntgorm leroeller^. HAIR BRACELETS, RINGS, BROOCHES, CHAINS, &c. PLAITED AND MOUNTED. OLD PLATED GOODS RE-FINISHED, EQUAL TO NEW. Silver Plate, Jewellery, and Watches Repaired. (Late A. Cheistie & Son), 23 ia:zc3-i3: sti^eet^ PERTH, MANUFACTURER OF HOSIERY Of all descriptions, in Cotton, Worsted, Lambs' Wool, Merino, and Silk, or made to Order. LADIES' AND GENTLEMEN'S ^ilk, Cotton, anb SEoollen ^\}xxi^ attb ^Mktt^, LADIES' AND GENTLEMEN'S DRAWERS, In Silk, Cotton, Worsted, Merino, and Lambs' Wool, either Kibbed or Plain. Of either Silk, Cotton, or Woollen, with Plain or Ribbed Bodies] ALSO, BELTS AND KNEE-CAPS. TARTAN HOSE OF EVERY VARIETY, Or made to Order. GLOVES AND MITTS, In Silk, Cotton, or Thread, in great Variety and Colour. FLANNEL SHOOTING JACKETS. ® €^9 CONFECTIONER AND e « 41, GEORGE STREET, COOKS FOR ALL KINDS OP ALSO ON HAND, ALL KINDS OF CAKES AND FANCY BISCUIT, j^jsru ICES PTO*a0^ ^^te mmU to ©vto- GINGER BEER, LEMONADE, AND SODA WATER. '*»- : THE POST-OFFICE PERTH DIRECTOEI FOR WITH A COPIOUS APPENDIX, CONTAINING A COMPLETE POST-OFFICE DIRECTORY, AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION. COMPILED AND ARRANGED BY JAMES MAESHALL, POST-OFFICE. WITH ^ pUtt of tl)e OTtts atiti d^nmxonn, ENGEAVED EXPRESSLY FOB THE WORK. PEETH PRINTED FOR THE PUBLISHER BY C. G. SIDEY, POST-OFFICE. -

Highland Perthshire Trail

HIGHLAND PERTHSHIRE TRAIL HISTORY, CULTURE AND LANDSCAPES OF HIGHLAND PERTHSHIRE THE HIGHLAND PERTHSHIRE TRAIL - SELF GUIDED WALKING SUMMARY Discover Scotland’s vibrant culture and explore the beautiful landscapes of Highland Perthshire on this gentle walking holiday through the heart of Scotland. The Perthshire Trail is a relaxed inn to inn walking holiday that takes in the very best that this wonderful area of the highlands has to offer. Over 5 walking days you will cover a total of 55 miles through some of Scotland’s finest walking country. Your journey through Highland Perthshire begins at Blair Atholl, a small highland village nestled on the banks of the River Garry. From Blair Atholl you will walk to Pitlochry, Aberfeldy, Kenmore, Fortingall and then to Kinloch Rannoch. Several rest days are included along the way so that you have time to explore the many visitor attractions that Perthshire has to offer the independent walker. Every holiday we offer features hand-picked overnight accommodation in high quality B&B’s, country inns, and guesthouses. Each is unique and offers the highest levels of welcome, atmosphere and outstanding local cuisine. We also include daily door to door baggage transfers, route notes and detailed maps and Tour: Highland Perthshire Trail pre-departure information pack as well as emergency support, should you need it. Code: WSSHPT1—WSSHPT2 Type: Self-Guided Walking Holiday Price: See Website HIGHLIGHTS Single Supplement: See Website Dates: April to October Walking Days: 5—7 Exploring Blair Castle, one of Scotland’s finest, and the beautiful Atholl Estate. Nights: 6—8 Start: Blair Atholl Visiting the fascinating historic sites at the Pass of Killiecrankie and Loch Tay. -

“For Christ and Covenant:” a Movement for Equal Consideration in Early Nineteenth Century Nova Scotia

“For Christ and Covenant:” A Movement for Equal Consideration in Early Nineteenth Century Nova Scotia. By Holly Ritchie A Thesis Submitted to Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, Nova Scotia in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History © Copyright Holly Ritchie, 2017 November, 2017, Halifax, Nova Scotia Approved: Dr. S. Karly Kehoe Supervisor Approved: Dr. John Reid Reader Approved: Dr. Jerry Bannister Examiner Date: 30 November 2017 1 Abstract “For Christ and Covenant:” A Movement for Equal Consideration in Early Nineteenth Century Nova Scotia. Holly Ritchie Reverend Dr. Thomas McCulloch is a well-documented figure in Nova Scotia’s educational historiography. Despite this, his political activism and Presbyterian background has been largely overlooked. This thesis offers a re-interpretation of the well-known figure and the Pictou Academy’s fight for permeant pecuniary aid. Through examining Scotland’s early politico-religious history from the Reformation through the Covenanting crusades and into the first disruption of the Church of Scotland, this thesis demonstrates that the language of political disaffection was frequently expressed through the language of religion. As a result, this framework of response was exported with the Scottish diaspora to Nova Scotia, and used by McCulloch to stimulate a movement for equal consideration within the colony. Date: 30 November 2017 2 Acknowledgements Firstly, to the wonderful Dr. S. Karly Kehoe, thank you for providing me with an opportunity beyond my expectations. A few lines of acknowledgement does not do justice to the impact you’ve had on my academic work, and my self-confidence. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

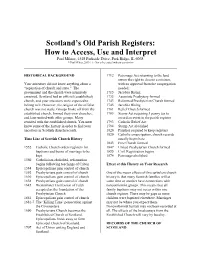

Scotland's Old Parish Registers: How to Access, Use and Interpret

Scotland’s Old Parish Registers: How to Access, Use and Interpret Paul Milner, 1548 Parkside Drive, Park Ridge, IL 6068 © Paul Milner, 2003-11 - Not to be copied without permission HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 1712 Patronage Act returning to the land owner the right to choose a minister, Your ancestors did not know anything about a with no approval from the congregation “separation of church and state.” The needed. government and the church were intimately 1715 Jacobite Rising entwined. Scotland had an official (established) 1733 Associate Presbytery formed church, and your ancestors were expected to 1743 Reformed Presbyterian Church formed belong to it. However, the religion of the official 1745 Jacobite Rising church was not static. Groups broke off from the 1761 Relief Church formed established church, formed their own churches, 1783 Stamp Act requiring 3 penny tax to and later united with other groups. Many record an event in the parish register reunited with the established church. You must 1793 Catholic Relief Act know some of the history in order to find your 1794 Stamp Act abolished ancestors in Scottish church records. 1820 Parishes required to keep registers 1829 Catholic emancipation, church records Time Line of Scottish Church History usually begin here 1843 Free Church formed 1552 Catholic Church orders registers for 1847 United Presbyterian Church formed baptisms and banns of marriage to be 1855 Civil Registration begins kept 1874 Patronage abolished 1560 Catholicism abolished, reformation begins following teachings of Calvin Effect of this History on Your Research 1584 Episcopalians gain control of church 1592 Presbyterians gain control of church One of the major effects of this turbulent church 1610 Episcopalians gain control of church history is that many Scottish families will at 1638 Presbyterians gain control of church some time or another have connections with 1645 Westminster Confession of Faith nonconformist groups. -

Pitlochry Faskally Killiecrankie Blair Atholl Calvine 83 87 Calvine

Pitlochry Faskally Killiecrankie Blair Atholl Calvine 83 87 MONDAYS TO SATURDAYS Summer timetable - Monday nearest 01 April to Saturday nearest 31 October operator EY EY EY EY EY EY EY EY EY EY EY EY route number 87 887 87 87 87 87 87 87 887 887 87 87 Sch Sch NSch MWF TTh Pitlochry Festival Theatre — — — 1110 1210 1340 — — — — 1730 1850 Pitlochry Community Hospital — — — 1115 1215 1345 — — — — 1735 Pitlochry High School — — — 1535 — 1535 1535 Pitlochry Fishers Hotel — 0805 — 1120 1220 1350 1535 1740 1855 Pitlochry West End car park 0750 1000 — 1225 — 1540 1540 1540 1540 1745 — Faskally campsite 0753 0809 1005 — 1230 — 1545 1545 1750 — Killiecrankie bus stop 0757 0813 1010 — 1235 — 1550 1550 1755 — Blair Castle 1017 — 1242 — 1557 — Blair Atholl Atholl Arms 0803 0821 1020 — 1245 — 1600 1600 1555 1555 1800 — House of Bruar 0806 — 1025 — 1250 — 1605 1605 — — 1805 — Calvine opp bus shelter 0808 — 1029 — 1254 — 1609 1609 — — 1809 — Old Struan road end 0809 — 1030 — 1255 — 1610 1610 — — 1810 — Calvine Blair Atholl Killiecrankie Faskally Pitlochry 83 87 MONDAYS TO SATURDAYS Summer timetable - Monday nearest 01 April to Saturday nearest 31 October operator EY EY EY EY EY EY EY EY EY EY route number 87 887 87 87 87 87 887 87 87 87 NSch Sch Sch TTh Old Struan road end 0810 — 0810 1030 — 1300 — 1610 — 1810 Calvine bus shelter 0812 — 0812 1032 — 1302 — 1612 — 1812 House of Bruar 0815 — 0815 1035 — 1305 — 1615 — 1815 Blair Atholl opposite Atholl Arms 0820 0825 0820 1040 — 1310 1555 1620 — 1820 Blair Castle 1042 — 1312 -

"For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh Mackay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2012 "For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh MacKay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland Andrew Phillip Frantz College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Frantz, Andrew Phillip, ""For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh MacKay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland" (2012). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 480. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/480 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF SO GOOD A CAUSE”: HUGH MACKAY, THE HIGHLAND WAR AND THE GLORIOUS REVOLUTION IN SCOTLAND A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors is History from the College of William and Mary in Virginia, by Andrew Phillip Frantz Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) _________________________________________ Nicholas Popper, Director _________________________________________ Paul Mapp _________________________________________ Simon Stow Williamsburg, Virginia April 30, 2012 Contents Figures iii Acknowledgements iv Introduction 1 Chapter I The Origins of the Conflict 13 Chapter II Hugh MacKay and the Glorious Revolution 33 Conclusion 101 Bibliography 105 iii Figures 1. General Hugh MacKay, from The Life of Lieutenant-General Hugh MacKay (1836) 41 2. The Kingdom of Scotland 65 iv Acknowledgements William of Orange would not have been able to succeed in his efforts to claim the British crowns if it were not for thousands of people across all three kingdoms, and beyond, who rallied to his cause. -

Erin and Alban

A READY REFERENCE SKETCH OF ERIN AND ALBAN WITH SOME ANNALS OF A BRANCH OF A WEST HIGHLAND FAMILY SARAH A. McCANDLESS CONTENTS. INTRODUCTION. PART I CHAPTER I PRE-HISTORIC PEOPLE OF BRITAIN 1. The Stone Age--Periods 2. The Bronze Age 3. The Iron Age 4. The Turanians 5. The Aryans and Branches 6. The Celto CHAPTER II FIRST HISTORICAL MENTION OF BRITAIN 1. Greeks 2. Phoenicians 3. Romans CHAPTER III COLONIZATION PE}RIODS OF ERIN, TRADITIONS 1. British 2. Irish: 1. Partholon 2. Nemhidh 3. Firbolg 4. Tuatha de Danan 5. Miledh 6. Creuthnigh 7. Physical CharacteriEtics of the Colonists 8. Period of Ollaimh Fodhla n ·'· Cadroc's Tradition 10. Pictish Tradition CHAPTER IV ERIN FROM THE 5TH TO 15TH CENTURY 1. 5th to 8th, Christianity-Results 2. 9th to 12th, Danish Invasions :0. 12th. Tribes and Families 4. 1169-1175, Anglo-Norman Conquest 5. Condition under Anglo-Norman Rule CHAPTER V LEGENDARY HISTORY OF ALBAN 1. Irish sources 2. Nemedians in Alban 3. Firbolg and Tuatha de Danan 4. Milesians in Alban 5. Creuthnigh in Alban 6. Two Landmarks 7. Three pagan kings of Erin in Alban II CONTENTS CHAPTER VI AUTHENTIC HISTORY BEGINS 1. Battle of Ocha, 478 A. D. 2. Dalaradia, 498 A. D. 3. Connection between Erin and Alban CHAPTER VII ROMAN CAMPAIGNS IN BRITAIN (55 B.C.-410 A.D.) 1. Caesar's Campaigns, 54-55 B.C. 2. Agricola's Campaigns, 78-86 A.D. 3. Hadrian's Campaigns, 120 A.D. 4. Severus' Campaigns, 208 A.D. 5. State of Britain During 150 Years after SeveTus 6. -

Victoria & Albert's Highland Fling

PROGRAMME 2 VICTORIA & ALBERT’S HIGHLAND FLING Introduction The Highlands are renowned throughout the world as a symbol of Scottish identity and we’re about to find out why. In this four-day walk we’re starting out at Pitlochry – gateway to the Cairngorms National Park – on a mountainous hike to the Queen’s residence at Balmoral. Until the 19th century, this area was seen by many as a mysterious and dangerous land. Populated by kilt-wearing barbarians, it was to be avoided by outsiders. We’re going to discover how all that changed, thanks in large part to an unpopular German prince and his besotted queen. .Walking Through History Day 1. Day 1 takes us through the Killiecrankie Pass, a battlefield of rebellious pre-Victorian Scotland. Then it’s on to an unprecedented royal visit at Blair Castle. Pitlochry to Blair Atholl, via the Killiecrankie Pass and Blair Castle. Distance: 12 miles Day 2. Things get a little more rugged with an epic hike through Glen Tilt and up Carn a’Chlamain. Then it’s on to Mar Lodge estate where we’ll discover how the Clearances made this one of the emptiest landscapes in Europe, and a playground for the rich. Blair Atholl to Mar Lodge, via Glen Tilt and Carn a’Chlamain. Distance: 23 miles Day 3. Into Royal Deeside, we get a taste of the Highland Games at Braemar, before reaching the tartan palace Albert built for his queen at Balmoral. Mar Lodge to Crathie, via Braemar and Balmoral Castle Distance: 20 miles Day 4. On our final day we explore the Balmoral estate. -

Scotland – North

Scotland – North Scotland was at the heart of Jacobitism. All four Jacobite risings - in 1689-91, 1715-16, 1719 and 1745-46 - took place either entirely (the first and third) or largely (the second and fourth) in Scotland. The north of Scotland was particularly important in the story of the risings. Two of them (in 1689-91 and 1719) took place entirely in the north of Scotland. The other two (in 1715-16 and 1745-46) began and ended in the north of Scotland, although both had wider theatres during the middle stages of the risings. The Jacobite movement in Scotland managed to attract a wide range of support, which is why more than one of the risings came close to succeeding. This support included Lowlanders as well as Highlanders, Episcopalians as well as Catholics (not to mention some Presbyterians and others), women as well as men, and an array of social groups and ages. This Scotland-North section has many Jacobite highlights. These include outstanding Jacobite collections in private houses such as Blair Castle, Scone Palace and Glamis Castle; state-owned houses with Jacobite links, such as Drum Castle and Corgarff Castle; and museums and exhibitions such as the West Highland Museum and the Culloden Visitor Centre. They also include places which played a vital role in Jacobite history, such as Glenfinnan, and the loyal Jacobite ports of the north-east, and battlefields (six of the land battles fought during the risings are in this section, together with several other skirmishes on land and sea). The decision has been made here to divide the Scottish sections into Scotland – South and Scotland – North, rather than the more traditional Highlands and Lowlands. -

The History of Cedarville College

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Faculty Books 1966 The iH story of Cedarville College Cleveland McDonald Cedarville University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books Part of the Nonfiction Commons Recommended Citation McDonald, Cleveland, "The iH story of Cedarville College" (1966). Faculty Books. 65. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books/65 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The iH story of Cedarville College Disciplines Creative Writing | Nonfiction Publisher Cedarville College This book is available at DigitalCommons@Cedarville: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books/65 CHAPTER I THE COVENANTERS Covenanters in Scotland. --The story of the Reformed Presby terians who began Cedarville College actually goes back to the Reformation in Scotland where Presbyterianism supplanted Catholicism. Several "covenants" were made during the strug gles against Catholicism and the Church of England so that the Scottish Presbyterians became known as the "covenanters." This was particularly true after the great "National Covenant" of 1638. 1 The Church of Scotland was committed to the great prin ciple "that the Lord Jesus Christ is the sole Head and King of the Church, and hath therein appointed a government distinct from that of the Civil magistrate. "2 When the English attempted to force the Episcopal form of Church doctrine and government upon the Scottish people, they resisted it for decades. The final ten years of bloody persecution and revolution were terminated by the Revolution Settlement of 1688, and by an act of Parliament in 1690 that established Presbyterianism in Scotland.