The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Cromdale Designation Record and Full Report Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh Mackay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2012 "For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh MacKay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland Andrew Phillip Frantz College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Frantz, Andrew Phillip, ""For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh MacKay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland" (2012). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 480. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/480 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF SO GOOD A CAUSE”: HUGH MACKAY, THE HIGHLAND WAR AND THE GLORIOUS REVOLUTION IN SCOTLAND A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors is History from the College of William and Mary in Virginia, by Andrew Phillip Frantz Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) _________________________________________ Nicholas Popper, Director _________________________________________ Paul Mapp _________________________________________ Simon Stow Williamsburg, Virginia April 30, 2012 Contents Figures iii Acknowledgements iv Introduction 1 Chapter I The Origins of the Conflict 13 Chapter II Hugh MacKay and the Glorious Revolution 33 Conclusion 101 Bibliography 105 iii Figures 1. General Hugh MacKay, from The Life of Lieutenant-General Hugh MacKay (1836) 41 2. The Kingdom of Scotland 65 iv Acknowledgements William of Orange would not have been able to succeed in his efforts to claim the British crowns if it were not for thousands of people across all three kingdoms, and beyond, who rallied to his cause. -

Scotland – North

Scotland – North Scotland was at the heart of Jacobitism. All four Jacobite risings - in 1689-91, 1715-16, 1719 and 1745-46 - took place either entirely (the first and third) or largely (the second and fourth) in Scotland. The north of Scotland was particularly important in the story of the risings. Two of them (in 1689-91 and 1719) took place entirely in the north of Scotland. The other two (in 1715-16 and 1745-46) began and ended in the north of Scotland, although both had wider theatres during the middle stages of the risings. The Jacobite movement in Scotland managed to attract a wide range of support, which is why more than one of the risings came close to succeeding. This support included Lowlanders as well as Highlanders, Episcopalians as well as Catholics (not to mention some Presbyterians and others), women as well as men, and an array of social groups and ages. This Scotland-North section has many Jacobite highlights. These include outstanding Jacobite collections in private houses such as Blair Castle, Scone Palace and Glamis Castle; state-owned houses with Jacobite links, such as Drum Castle and Corgarff Castle; and museums and exhibitions such as the West Highland Museum and the Culloden Visitor Centre. They also include places which played a vital role in Jacobite history, such as Glenfinnan, and the loyal Jacobite ports of the north-east, and battlefields (six of the land battles fought during the risings are in this section, together with several other skirmishes on land and sea). The decision has been made here to divide the Scottish sections into Scotland – South and Scotland – North, rather than the more traditional Highlands and Lowlands. -

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-Àite Ann an Sgìre Prìomh Bhaile Na Gàidhealtachd

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Author: Roddy Maclean Photography: all images ©Roddy Maclean except cover photo ©Lorne Gill/NatureScot; p3 & p4 ©Somhairle MacDonald; p21 ©Calum Maclean. Maps: all maps reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/ except back cover and inside back cover © Ashworth Maps and Interpretation Ltd 2021. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2021. Design and Layout: Big Apple Graphics Ltd. Print: J Thomson Colour Printers Ltd. © Roddy Maclean 2021. All rights reserved Gu Aonghas Seumas Moireasdan, le gràdh is gean The place-names highlighted in this book can be viewed on an interactive online map - https://tinyurl.com/ybp6fjco Many thanks to Audrey and Tom Daines for creating it. This book is free but we encourage you to give a donation to the conservation charity Trees for Life towards the development of Gaelic interpretation at their new Dundreggan Rewilding Centre. Please visit the JustGiving page: www.justgiving.com/trees-for-life ISBN 978-1-78391-957-4 Published by NatureScot www.nature.scot Tel: 01738 444177 Cover photograph: The mouth of the River Ness – which [email protected] gives the city its name – as seen from the air. Beyond are www.nature.scot Muirtown Basin, Craig Phadrig and the lands of the Aird. Central Inverness from the air, looking towards the Beauly Firth. Above the Ness Islands, looking south down the Great Glen. -

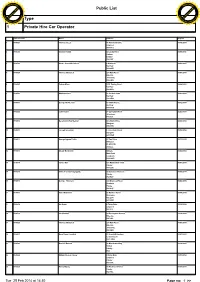

Public List Type 1 Private Hire Car Operator

Ch F-X ang PD e Public List w w m w Click to buy NOW! o . .c tr e Type ac ar ker-softw 1 Private Hire Car Operator Reference No. Name Address Expires 1 PH0501 Thomas Steen 11 Richmond Drive 31/10/2014 Linwood PA3 3TQ 2 PH0502 Stephen Smith 42 Lochy Place 31/08/2015 Linburn Erskine PA8 6AY 3 PH0503 Stuart James McCulloch 4 Kirklands 28/02/2015 Renfrew PA4 8HR 4 PH0504 Thomas McGarrell 287 Main Road 31/03/2014 Elderslie Johnstone PA5 9ED 5 PH0505 Farhan Khan 135F Paisley Road 30/09/2014 Renfrew PA4 8XA 6 PH0506 Matthew Kane 26 Cockels Loan 30/09/2014 Renfrew PA4 0RG 7 PH0507 George McPherson 40 Third Avenue 31/12/2014 Renfrew PA4 OPX 8 PH0508 John Deans 37 Springfield Park 30/06/2014 Johnstone PA5 8JS 9 PH0510 Derek John Hay Stewart 22 Lintlaw Drive 28/02/2014 Glasgow G52 2NS 10 PH0511 Joseph Sebastian 5 Crosstobs Road 30/09/2014 Glasgow G53 5SW 11 PH0512 George Ingram Dickie 44 Yair Drive 31/12/2015 Hillington GLASGOW G52 2LE 12 PH0513 Alistair Borthw ick Kilblane 30/04/2014 Main Road Langbank PA14 6XP 13 PH0514 James Muir 10c Maxwellton Court 30/06/2014 Paisley PA1 2UE 14 PH0515 Shibu Thomas Payyappilly 28 Denewood Avenue 31/03/2014 Paisley PA2 8DY 15 PH0516 George Thomson 222 Braehead Road 30/04/2015 Glenburn Paisley PA2 8QF 16 PH0517 Alan McDonald 21 Murroes Road 31/08/2014 Drumoyne Glasgow G51 4NR 17 PH0518 Ian Grant 4 Finlay Drive 30/09/2014 Linwood PA3 3LJ 18 PH0519 Iain Waddell 64 Dunvegean Avenue 31/10/2014 Elderslie PA5 9NL 19 PH0520 Thomas McGarrell 287 Main Road 31/08/2014 Elderslie Johnstone PA5 9ED 20 PH0521 Hazel Jane Crawford 64 Crookhill Gardens 31/01/2014 Lochwinnoch PA12 4BA 21 PH0522 David O'Donnell 32 Glendower Way 31/10/2015 Foxbar Paisley PA2 22 PH0524 William Steven Calvey 2 Irvine Drive 31/03/2014 Linwood Paisley PA3 3TA 23 PH0525 Henry Mejury 33 Birchwood Drive 31/03/2014 Paisley PA2 9NE Tue 25 Feb 2014 at 14:30 Page no: 1 >> Ch F-X ang PD e Reference No. -

The Dalradian Rocks of the North-East Grampian Highlands of Scotland

Revised Manuscript 8/7/12 Click here to view linked References 1 2 3 4 5 The Dalradian rocks of the north-east Grampian 6 7 Highlands of Scotland 8 9 D. Stephenson, J.R. Mendum, D.J. Fettes, C.G. Smith, D. Gould, 10 11 P.W.G. Tanner and R.A. Smith 12 13 * David Stephenson British Geological Survey, Murchison House, 14 West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA. 15 [email protected] 16 0131 650 0323 17 John R. Mendum British Geological Survey, Murchison House, West 18 Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA. 19 Douglas J. Fettes British Geological Survey, Murchison House, West 20 Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA. 21 C. Graham Smith Border Geo-Science, 1 Caplaw Way, Penicuik, 22 Midlothian EH26 9JE; formerly British Geological Survey, Edinburgh. 23 David Gould formerly British Geological Survey, Edinburgh. 24 P.W. Geoff Tanner Department of Geographical and Earth Sciences, 25 University of Glasgow, Gregory Building, Lilybank Gardens, Glasgow 26 27 G12 8QQ. 28 Richard A. Smith formerly British Geological Survey, Edinburgh. 29 30 * Corresponding author 31 32 Keywords: 33 Geological Conservation Review 34 North-east Grampian Highlands 35 Dalradian Supergroup 36 Lithostratigraphy 37 Structural geology 38 Metamorphism 39 40 41 ABSTRACT 42 43 The North-east Grampian Highlands, as described here, are bounded 44 to the north-west by the Grampian Group outcrop of the Northern 45 Grampian Highlands and to the south by the Southern Highland Group 46 outcrop in the Highland Border region. The Dalradian succession 47 therefore encompasses the whole of the Appin and Argyll groups, but 48 also includes an extensive outlier of Southern Highland Group 49 strata in the north of the region. -

Survey of Scottish Witchcraft Database Documentation and Description

1 Survey of Scottish Witchcraft Database Documentation and Description Contents of this Document I. Database Description (pp. 2-14) A. Description B. Database field types C. Miscellaneous database information D. Entity Models 1. Overview 2. Case attributes 3. Trial attributes II. List of tables and fields (pp. 15-29) III. Data Value Descriptions (pp. 30-41) IV. Database Provenance (pp. 42-54) A. Descriptions of sources used B. Full bibliography of primary, printed primary and secondary sources V. Methodology (pp. 55-58) VI. Appendices (pp. 59-78) A. Modernised/Standardised Last Names B. Modernised/Standardised First Names C. Parish List – all parishes in seventeenth century Scotland D. Burgh List – Royal burghs in 1707 E. Presbytery List – Presbyteries used in the database F. County List – Counties used in the database G. Copyright and citation protocol 2 Database Documents I. DATABASE DESCRIPTION A. DESCRIPTION (in text form) DESCRIPTION OF SURVEY OF SCOTTISH WITCHCRAFT DATABASE INTRODUCTION The following document is a description and guide to the layout and design of the ‘Survey of Scottish Witchcraft’ database. It is divided into two sections. In the first section appropriate terms and concepts are defined in order to afford accuracy and precision in the discussion of complicated relationships encompassed by the database. This includes relationships between accused witches and their accusers, different accused witches, people and prosecutorial processes, and cultural elements of witchcraft belief and the processes through which they were documented. The second section is a general description of how the database is organised. Please see the document ‘Description of Database Fields’ for a full discussion of every field in the database, including its meaning, use and relationships to other fields and/or tables. -

CNPA.Paper.1680.Comm

Your Community … Your Plan Community Statements CONTENTS The Angus Glens 01 Glenshee 12 Aviemore and Vicintiy 02 Grantown-on-Spey 13 Ballater 03 Killicrankie 14 Blair Atholl 04 Kincraig 15 Boat of Garten 05 Kingussie 16 Braemar 06 Laggan 17 Carr-Bridge 07 Nethy Bridge 18 Cromdale and Advie 08 Newtonmore 19 Dalwhinnie 09 Strath Don 20 Dulnain Bridge 10 Tomintoul 21 Glenlivet 11 YOUR COMMUNITY ... YOUR PLAN Living in the Angus Glens Statement The Angus area of the Cairngorm National Park covers the isolated upper parts of the Angus Glens. While the „Angus Glens‟ are a distinct community, have a thriving website and a sense of cohesion, the Park boundary cuts this identified area in half. Only 50 people live in the CNP area, but while the responses in this research include comments about the CNP boundaries or feel it does not affect them, many people in the Glens feel ownership of the Park and want to engage with it. Some suggestions for this include strengthening links with Angus Council and relevant community councils. Respondents value their landscape and its vistas of high hills, glens and forests both as a special feature of life here and as a resource for tourism, creative employment, and active forestry and estate activities. People want the landscape to remain open to local people, farmers and leisure users and some worry that not all local estates are willing to work with communities to achieve this. People value traditional building styles and their community buildings such as the Retreat at Glen Esk. However, affordable housing for people living and working in the Glens is in short supply and is needed to bring people in/retain young people to support community groups and local employment and business initiatives. -

The Landscapes of Scotland 21 Speyside

The Landscapes of Scotland Descriptions 21 - 30 21 Speyside 22 Ladder and Cromdale Hills 23 Gordon and Garioch 24 Small Isles and Ardamurchan 25 Morar and Knoydart 26 Laggan and Ben Alder 27 Drumochter 28 Cairngorm Massif 29 Upper Deeside 30 Deeside and Donside 21 Speyside Description This is a long, wide and varied strath containing wetlands, woodland, farmland, and settlements. Distinctive Caledonian pine and birch woods extend uphill, giving way to open moorland on the higher adjacent hills. The valley forms a major north-south transport corridor: road and rail routes, and busy settlements, contrast with the tranquillity of the river and hills. Prehistoric settlement remains are common, and some military structures such as Ruthven barracks, are still prominent. The architectural character is predominantly mid to late 18 th century, as a result of improvements in agriculture and the opening of the railway from Perth to Aviemore in 1863. Distilleries form frequent landmarks amongst the settlements and steadings. Key technical information sources Selected creative associations LCA: Cairngorms (Report No 75) Music [Moray & Nairn small part] Haughs of Cromdale (traditional) NHF: North East Coast (12) HLA: XX Naismith - Buildings of the Scottish Countryside pp 188-191, 191-195 1 The Landscapes of Scotland 22 Ladder and Cromdale Hills Description This range of moorland hills forms simple skylines when viewed from the intervening glens. They seem large until compared to the Cairngorm Mountains immediately to the south. The uplands are heather-clad and managed for grouse. Now sparsely populated, the remains of shielings are scattered on the hills, demonstrating the importance of transhumance to past communities. -

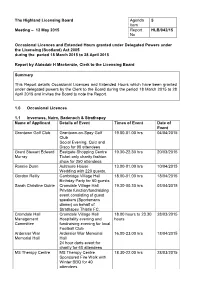

Report Style

The Highland Licensing Board Agenda 5 Item Meeting – 12 May 2015 Report HLB/042/15 No Occasional Licences and Extended Hours granted under Delegated Powers under the Licensing (Scotland) Act 2005 during the period 18 March 2015 to 28 April 2015 Report by Alaisdair H Mackenzie, Clerk to the Licensing Board Summary This Report details Occasional Licences and Extended Hours which have been granted under delegated powers by the Clerk to the Board during the period 18 March 2015 to 28 April 2015 and invites the Board to note the Report. 1.0 Occasional Licences 1.1 Inverness, Nairn, Badenoch & Strathspey Name of Applicant Details of Event Times of Event Date of Event Grantown Golf Club Grantown-on-Spey Golf 19.00-01.00 hrs 04/04/2015 Club Social Evening, Quiz and Disco for 90 attendees Grant Stewart Edward Eastgate Shopping Centre 19.30-22.30 hrs 20/03/2015 Murray Ticket only charity fashion show for 250 attendees Ronnie Dunn Aultmore House 13.00-01.00 hrs 10/04/2015 Wedding with 220 guests. Gordon Reilly Carrbridge Village Hall 18.00-01.00 hrs 18/04/2015 Birthday Party for 60 guests Sarah Christine Quirie Cromdale Village Hall 19.30-00.30 hrs 03/04/2015 Private function/fundraising event consisting of guest speakers (Sportsmans dinner) on behalf of Strathspey Thistle FC. Cromdale Hall Cromdale Village Hall 18.00 hours to 23.30 28/03/2015 Management Hospitality evening and hours Committee fundraising evening for local Football Club Ardersier War Ardersier War Memorial 16.00-23.00 hrs 18/04/2015 Memorial Hall Hall 24 hour darts event for charity for 60 attendees MS Therapy Centre MS Therapy Centre 18.30-22.00 hrs 28/03/2015 Sponsored Fire Walk with Winter BBQ for 40 attendees Kenneth MacKay Moy Game Fair Selling of Friday, 7 August and 07/08/2015 alcohol for consumption off Sat 8 August: – premises, also small 1cl 10.00-19.00 hrs 8/08/2015 samples offered at stand Moy Game Fair Fraser Park Bowling Fraser Park Bowling Club 12.00-18.00 hrs 18/04/2015 Club Opening of Bowling Club for 2015 Summer Season for 120 attendees. -

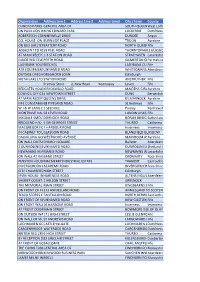

I General Area of South Quee

Organisation Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Address Line3 City / town County DUNDAS PARKS GOLFGENERAL CLUB- AREA IN CLUBHOUSE OF AT MAIN RECEPTION SOUTH QUEENSFERRYWest Lothian ON PAVILLION WALL,KING 100M EDWARD FROM PARK 3G PITCH LOCKERBIE Dumfriesshire ROBERTSON CONSTRUCTION-NINEWELLS DRIVE NINEWELLS HOSPITAL*** DUNDEE Angus CCL HOUSE- ON WALLBURNSIDE BETWEEN PLACE AG PETERS & MACKAY BROS GARAGE TROON Ayrshire ON BUS SHELTERBATTERY BESIDE THE ROAD ALBERT HOTEL NORTH QUEENSFERRYFife INVERKEITHIN ADJACENT TO #5959 PEEL PEEL ROAD ROAD . NORTH OF ENT TO TRAIN STATION THORNTONHALL GLASGOW AT MAIN RECEPTION1-3 STATION ROAD STRATHAVEN Lanarkshire INSIDE RED TELEPHONEPERTH ROADBOX GILMERTON CRIEFFPerthshire LADYBANK YOUTHBEECHES CLUB- ON OUTSIDE WALL LADYBANK CUPARFife ATR EQUIPMENTUNNAMED SOLUTIONS ROAD (TAMALA)- IN WORKSHOP OFFICE WHITECAIRNS ABERDEENAberdeenshire OUTSIDE DREGHORNDREGHORN LOAN HALL LOAN Edinburgh METAFLAKE LTD UNITSTATION 2- ON ROAD WALL AT ENTRANCE GATE ANSTRUTHER Fife Premier Store 2, New Road Kennoway Leven Fife REDGATES HOLIDAYKIRKOSWALD PARK- TO LHSROAD OF RECEPTION DOOR MAIDENS GIRVANAyrshire COUNCIL OFFICES-4 NEWTOWN ON EXT WALL STREET BETWEEN TWO ENTRANCE DOORS DUNS Berwickshire AT MAIN RECEPTIONQUEENS OF AYRSHIRE DRIVE ATHLETICS ARENA KILMARNOCK Ayrshire FIFE CONSTABULARY68 PIPELAND ST ANDREWS ROAD POLICE STATION- AT RECEPTION St Andrews Fife W J & W LANG LTD-1 SEEDHILL IN 1ST AID ROOM Paisley Renfrewshire MONTRAVE HALL-58 TO LEVEN RHS OFROAD BUILDING LUNDIN LINKS LEVENFife MIGDALE SMOLTDORNOCH LTD- ON WALL ROAD AT -

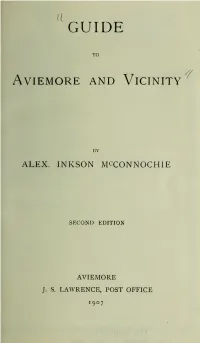

Guide to Aviemore and Vicinity

[ GUIDE TO AVIEMORE AND VlCINITY BY ALEX. INKSON M c CONNOCHIE SECOND EDITION AVIEMORE J. S. LAWRENCE, POST OFFICE 1907 DRIVES. HP HE following List of Drives includes all the favourite -* excursions which are generally made by visitors at Aviemore. The figures within brackets refer to the pages of the Guide where descriptions will be found. For hires, etc., apply at the Post Office. I. Loch an Eilein (18), 3 miles, and Loch Gamhna (22), 4 miles, via Inverdruie (14) and The Croft (18) ; return via Polchar (18) and Inverdruie. II. Lynwilg (33), Kinrara House (34), and Tor Alvie (33). III. Round by Kincraig— passing Lynwilg (33), Loch Alvie (36), Tor Alvie (33), Kincraig (41), Loch Insh (42), Insh Church (42), teshie Bridge (45), Rothiemurchus Church (14), The Doune (14), and Inverdruie (14); or vice-versa. IV. Glen Feshie (45) via Kincraig (41), reluming from Feshie Bridge as in No. III. ; or vice-versa. V. Carr Bridge (63), 7 miles. VI. Round by Boat of Garten via Carr Bridge road to Kinveachy (63), Boat of Garten (66), Kincardine Chuch (52), Loch Pityoulish (51), Coylum Bridge (24) and Inverdruie (14) ; or vice-versa. VII. Loch Eunach (26) via Inverdruie (14), Coylum Bridge (24) and Glen Eunach (24). The return journey may be made via Loch an Eilein (18) and The Croft (18), or Polchar (18). Braeriach, Cairn Toul and Sgoran Dubh are best ascended from Glen Eunach. VIII. Aultdrue (27) via Inverdruie (14), Coylum Bridge (24) and Cross Roads (27). The entrance to the Larig Ghru (27) is near Aultdrue. Ben Muich Dhui or Braeriach may be ascended from the Larig Ghru. -

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Killiecrankie Designation

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Killiecrankie The Inventory of Historic Battlefields is a list of nationally important battlefields in Scotland. A battlefield is of national importance if it makes a contribution to the understanding of the archaeology and history of the nation as a whole, or has the potential to do so, or holds a particularly significant place in the national consciousness. For a battlefield to be included in the Inventory, it must be considered to be of national importance either for its association with key historical events or figures; or for the physical remains and/or archaeological potential it contains; or for its landscape context. In addition, it must be possible to define the site on a modern map with a reasonable degree of accuracy. The aim of the Inventory is to raise awareness of the significance of these nationally important battlefield sites and to assist in their protection and management for the future. Inventory battlefields are a material consideration in the planning process. The Inventory is also a major resource for enhancing the understanding, appreciation and enjoyment of historic battlefields, for promoting education and stimulating further research, and for developing their potential as attractions for visitors. Designation Record and Full Report Contents Name - Context Alternative Name(s) Battlefield Landscape Date of Battle - Location Local Authority - Terrain NGR Centred - Condition Date of Addition to Inventory Archaeological and Physical Date of Last Update Remains and