“For Christ and Covenant:” a Movement for Equal Consideration in Early Nineteenth Century Nova Scotia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society

I I. L /; I; COLLECTIONS OF THE j^olja Scotia ^isitoncal ^otitiv ''Out of monuments, names, wordes, proverbs, traditions, private records, and evidences, fragments of stories, passages of bookes, and the like, we do save, and recover somewhat from the deluge of time."—Lord Bacon: The Advancement of Learning. "A wise nation preserves its records, gathers up its muniments, decorates the tombs' of its illustrious dead, repairs its great structures, and fosters national pride and love of country, by perpetual re- ferences to the sacrifices and glories of the past."—Joseph Howe. VOLUME XVII. HALIFAX, N. S. Wm. Macnab & Son, 1913. FI034 Cef. 1 'TAe care which a nation devotes to the preservation of the monuments of its past may serve as a true measure of the degree of civilization to which it has attained.'' {Les Archives Principales de Moscou du Ministere des Affairs Etrangeres Moscow, 1898, p. 3.) 'To discover and rescue from the unsparing hand of time the records which yet remain of the earliest history of Canada. To preserve while in our power, such documents as may he found amid the dust of yet unexplored depositories, and which may prove important to general history, and to the particular history of this province.'" — Quebec Literary and Historical Society. NATIONAL MONUMENTS. (By Henry Van Dyke). Count not the cost of honour to the deadl The tribute that a mighty nation pays To those who loved her well in former days Means more than gratitude glory fled for ; For every noble man that she hath bred, Immortalized by art's immortal praise, Lives in the bronze and marble that we raise, To lead our sons as he our fathers led. -

The Ojibwa: 1640-1840

THE OJIBWA: 1640-1840 TWO CENTURIES OF CHANGE FROM SAULT STE. MARIE TO COLDWATER/NARROWS by JAMES RALPH HANDY A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts P.JM'0m' Of. TRF\N£ }T:·mf.RRLAO -~ in Histor;y UN1V"RS1TY O " · Waterloo, Ontario, 1978 {§) James Ralph Handy, 1978 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. I authorize the University of Waterloo to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize the University of Waterloo to reproduce this thesis by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the pur pose of scholarly research. 0/· (ii) The University of Waterloo requires the signature of all persons using or photo copying this thesis. Please sign below, and give address and date. (iii) TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1) Title Page (i) 2) Author's Declaration (11) 3) Borrower's Page (iii) Table of Contents (iv) Introduction 1 The Ojibwa Before the Fur Trade 8 - Saulteur 10 - growth of cultural affiliation 12 - the individual 15 Hurons 20 - fur trade 23 - Iroquois competition 25 - dispersal 26 The Fur Trade Survives: Ojibwa Expansion 29 - western villages JO - totems 33 - Midiwewin 34 - dispersal to villages 36 Ojibwa Expansion Into the Southern Great Lakes Region 40 - Iroquois decline 41 - fur trade 42 - alcohol (iv) TABLE OF CONTENTS (Cont'd) Ojibwa Expansion (Cont'd) - dependence 46 10) The British Trade in Southern -

THE BRITISH ARMY in the LOW COUNTRIES, 1793-1814 By

‘FAIRLY OUT-GENERALLED AND DISGRACEFULLY BEATEN’: THE BRITISH ARMY IN THE LOW COUNTRIES, 1793-1814 by ANDREW ROBERT LIMM A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY. University of Birmingham School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law October, 2014. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The history of the British Army in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars is generally associated with stories of British military victory and the campaigns of the Duke of Wellington. An intrinsic aspect of the historiography is the argument that, following British defeat in the Low Countries in 1795, the Army was transformed by the military reforms of His Royal Highness, Frederick Duke of York. This thesis provides a critical appraisal of the reform process with reference to the organisation, structure, ethos and learning capabilities of the British Army and evaluates the impact of the reforms upon British military performance in the Low Countries, in the period 1793 to 1814, via a series of narrative reconstructions. This thesis directly challenges the transformation argument and provides a re-evaluation of British military competency in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. -

Aims 6Th Annual High School Report Card (Rc6)

AIMS 6TH ANNUAL HIGH SCHOOL REPORT CARD (RC6) Nova Scotia High Schools Two years ago, a ruling by Nova Scotia’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Review Officer confirmed that the release of student achievement data was in the public interest. However, AIMS is still not able to report locally assigned exam grades or attendance in Nova Scotia schools, as some boards are still not able to access this information or simply refuse to do so. Following the closing of Queen Elizabeth High School in Halifax, last year’s top ranked school, we were assured a new school at the top of the rankings. Cape Breton Highlands Academy in Terre Noire jumped from third place in RC5 to take over the number one spot in the province, maintaining an ‘A-’ grade. Cape Breton Highlands was the only school in Nova Scotia to achieve an ‘A’ grade, with Charles P. Allen in Bedford also maintaining its ‘B+’ grade from last year to claim second spot in the rankings. Dalbrae Academy in Southwest Mabou saw its grade drop from an ‘A-’ to a ‘B+’ but still finished third overall. Several schools saw improvements of two grade levels. Rankin School of the Narrows and Pictou Academy-Dr. T. McCulloch School both improved from a ‘C+’ to a ‘B’ and finished eighth and ninth overall, respectively. Canso Academy (‘C’ to ‘B-’) and Annapolis West Education Centre (‘C’ to ‘B-’) also improved by two grade levels. Springhill Junior-Senior High School was the only school to see its grade decline more than two levels, falling from a ‘B-’ to a ‘C-’. -

The Church Militant: the American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92

The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Peter Walker All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker This dissertation is a study of the loyalist Church of England clergy in the American Revolution. By reconstructing the experience and identity of this largely-misunderstood group, it sheds light on the relationship between church and empire, the role of religious pluralism and toleration in the American Revolution, the dynamics of loyalist politics, and the religious impact of the American Revolution on Britain. It is based primarily on the loyalist clergy’s own correspondence and writings, the records of the American Loyalist Claims Commission, and the archives of the SPG (the Church of England’s missionary arm). The study focuses on the New England and Mid-Atlantic colonies, where Anglicans formed a religious minority and where their clergy were overwhelmingly loyalist. It begins with the founding of the SPG in 1701 and its first forays into America. It then examines the state of religious pluralism and toleration in New England, the polarising contest over the proposed creation of an American bishop after the Seven Years’ War, and the role of the loyalist clergy in the Revolutionary War itself, focusing particularly on conflicts occasioned by the Anglican liturgy and Book of Common Prayer. -

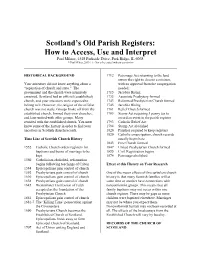

Scotland's Old Parish Registers: How to Access, Use and Interpret

Scotland’s Old Parish Registers: How to Access, Use and Interpret Paul Milner, 1548 Parkside Drive, Park Ridge, IL 6068 © Paul Milner, 2003-11 - Not to be copied without permission HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 1712 Patronage Act returning to the land owner the right to choose a minister, Your ancestors did not know anything about a with no approval from the congregation “separation of church and state.” The needed. government and the church were intimately 1715 Jacobite Rising entwined. Scotland had an official (established) 1733 Associate Presbytery formed church, and your ancestors were expected to 1743 Reformed Presbyterian Church formed belong to it. However, the religion of the official 1745 Jacobite Rising church was not static. Groups broke off from the 1761 Relief Church formed established church, formed their own churches, 1783 Stamp Act requiring 3 penny tax to and later united with other groups. Many record an event in the parish register reunited with the established church. You must 1793 Catholic Relief Act know some of the history in order to find your 1794 Stamp Act abolished ancestors in Scottish church records. 1820 Parishes required to keep registers 1829 Catholic emancipation, church records Time Line of Scottish Church History usually begin here 1843 Free Church formed 1552 Catholic Church orders registers for 1847 United Presbyterian Church formed baptisms and banns of marriage to be 1855 Civil Registration begins kept 1874 Patronage abolished 1560 Catholicism abolished, reformation begins following teachings of Calvin Effect of this History on Your Research 1584 Episcopalians gain control of church 1592 Presbyterians gain control of church One of the major effects of this turbulent church 1610 Episcopalians gain control of church history is that many Scottish families will at 1638 Presbyterians gain control of church some time or another have connections with 1645 Westminster Confession of Faith nonconformist groups. -

NOVA SCOTIA Crime Stoppers 14TH Annual Awareness Guide

NOVA SCOTIA Crime StopperS 14TH Annual Awareness Guide We Want To Live In A Safe Community Don’t Hide It... Tell It “Crime Stoppers wants your information, not your name” 1-800-222-TIPS (8477) Text Your Tip . TIP202 to “Crimes” (274637) Secure Web Tips . www.crimestoppers.ns.ca ANONYMITY GUARANTEED. CASH AWARDS PAID TOGETHER WE CAN ERASE CRIME TUNED IN TO OUR COMMUNITY EastLink TV is very proud to support Nova Scotia CRIME STOPPERS. Because it’s our home too. 1-800-222-8477 (TIPS) www.crimestoppers.ns.ca 14th Annual Awareness Guide 1 Table of Contents 14th Annual Awareness Guide Congratulatory Messages The Honourable Darrell Dexter . .1 The Honourable Ross Landry . .3 NS Crime Stoppers President - John O’Reilly . .5 Canadian Crime Stoppers Chair – Ralph Page . .7 NS Crime Stoppers Police Coordinator – Gary Frail . .7 RCMP Assistant Commissioner – Alphonse MacNeil . .9 Halifax Regional Police Chief - Jean-Michel Blais . .10 Nova Scotia Crime Stoppers Civilian Coordinator – Ron Cheverie . .11 Publisher’s Page – Mark Fenety . .13 Articles / Stories of Interest The Story of Crime Stoppers . .15 Crime Stoppers – Nova Scotia . .17 Crime of the Week Stories . .53 Bullying . .63 Contraband Cigarettes . .65 Statistics on Human Trafficking – It’s Happening Here . .67 page 19 Crime Stoppers Photo Album Provincial Board . .21 Annapolis Valley . .25 Antigonish . .27 Colchester and Area . .29 Cumberland County . .33 East Hants . .35 Halifax . .37 Lunenburg County . .41 Pictou County . .45 Queens County . .47 ...see page 53 West Hants County . .49 Update: Amber Kirwan Disappearance (Monument Unveiled) . .51 Memoriams . .72 Advertisers’ Index . .71 2 14th Annual Awareness Guide www.crimestoppers.ns.ca Honourable Ross Landry On behalf of the province of Nova Scotia, I would like to extend a sincere thanks to everyone involved in Crime Stoppers for your part in making Nova Scotia a better and safer place to live. -

The Cochran-Inglis Family of Halifax

ITOIBUoRA*r| j|orooiio»BH| iwAWMOTOIII THE COCHRAN-INGLIS FAMILY Gift Author MAY 22 mo To the Memory OF SIR JOHN EARDLEY WILMOT INGLIS, K.C. B. HERO OF LUCKNOW A Distinguished Nova Scotian WHO ARDENTLY LOVED HIS Native Land Press or J. R. Finduy, 111 Brunswick St., Halifax, n.6. THE COCHRAN-INGLIS FAMILY OF HALIFAX BY EATON, REV. ARTHUR WENTWORTH HAMILTON «« B. A. AUTHOB 07 •' THE CHUBCH OF ENGLAND IN NOVA SCOTIA AND THE TOET CLEBGT OF THE REVOLUTION." "THE NOVA SCOTIA BATONS,'" 1 "THE OLIVEBTOB HAHILTONS," "THE EI.MWOOD BATONS." THE HON. LT.-COL. OTHO HAMILTON OF 01XVE8T0B. HIS 80NS CAFT. JOHN" AND LT.-COL. OTHO 2ND, AND BIS GBANDSON SIB EALPH," THE HAMILTONB OF DOVSB AND BEHWICK," '"WILLIAM THOBNE AND SOME OF HIS DESCENDANTS." "THE FAMILIES OF EATON-SUTHEBLAND, LATTON-HILL," AC., AC. HALIFAX, N. S. C. H. Ruggi.es & Co. 1899 c^v GS <\o to fj» <@ifi Aatkair unkj «¦' >IJ COCHRAN -IMJLIS Among Nova Scotia families that have risen to a more than local prominence it willhardly be questioned that the Halifax Cochran "family withits connections, on the whole stands first. In The Church of England inNova Scotia and the Tory Clergy of the Revolution", and in a more recent family monograph entitled "Eaton —Sutherland; I,ayton-Hill," the Cochrans have received passing notice, but in the following pages for the first time a connected account of this important family willbe found. The facts here given are drawn chiefly from parish registers, biographical dictionaries, the British Army Lists, tombstones, and other recognized sources of authority for family history, though some, as for example the record of the family of the late Sir John Inglis, given the author by Hon. -

"For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh Mackay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2012 "For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh MacKay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland Andrew Phillip Frantz College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Frantz, Andrew Phillip, ""For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh MacKay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland" (2012). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 480. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/480 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF SO GOOD A CAUSE”: HUGH MACKAY, THE HIGHLAND WAR AND THE GLORIOUS REVOLUTION IN SCOTLAND A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors is History from the College of William and Mary in Virginia, by Andrew Phillip Frantz Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) _________________________________________ Nicholas Popper, Director _________________________________________ Paul Mapp _________________________________________ Simon Stow Williamsburg, Virginia April 30, 2012 Contents Figures iii Acknowledgements iv Introduction 1 Chapter I The Origins of the Conflict 13 Chapter II Hugh MacKay and the Glorious Revolution 33 Conclusion 101 Bibliography 105 iii Figures 1. General Hugh MacKay, from The Life of Lieutenant-General Hugh MacKay (1836) 41 2. The Kingdom of Scotland 65 iv Acknowledgements William of Orange would not have been able to succeed in his efforts to claim the British crowns if it were not for thousands of people across all three kingdoms, and beyond, who rallied to his cause. -

Historical Records of the 79Th Cameron Highlanders

%. Z-. W ^ 1 "V X*"* t-' HISTORICAL RECORDS OF THE 79-m QUEEN'S OWN CAMERON HIGHLANDERS antr (Kiritsft 1m CAPTAIN T. A. MACKENZIE, LIEUTENANT AND ADJUTANT J. S. EWART, AND LIEUTENANT C. FINDLAY, FROM THE ORDERLY ROOM RECORDS. HAMILTON, ADAMS & Co., 32 PATERNOSTER Row. JDebonport \ A. H. 111 112 FOUE ,STRSET. SWISS, & ; 1887. Ms PRINTED AT THE " " BREMNER PRINTING WORKS, DEVOXPORT. HENRY MORSE STETHEMS ILLUSTRATIONS. THE PHOTOGRAVURES are by the London Typographic Etching Company, from Photographs and Engravings kindly lent by the Officers' and Sergeants' Messes and various Officers of the Regiment. The Photogravure of the Uniform Levee Dress, 1835, is from a Photograph of Lieutenant Lumsden, dressed in the uniform belonging to the late Major W. A. Riach. CONTENTS. PAGK PREFACE vii 1793 RAISING THE REGIMENT 1 1801 EGYPTIAN CAMPAIGN 16 1808 PENINSULAR CAMPAIGN .. 27 1815 WATERLOO CAMPAIGN .. 54 1840 GIBRALTAR 96 1848 CANADA 98 1854 CRIMEAN CAMPAIGN 103 1857 INDIAN MUTINY 128 1872 HOME 150 1879 GIBRALTAR ... ... .. ... 161 1882 EGYPTIAN CAMPAIGN 166 1884 NILE EXPEDITION ... .'. ... 181 1885 SOUDAN CAMPAIGN 183 SERVICES OF THE OFFICERS 203 SERVICES OF THE WARRANT OFFICERS ETC. .... 291 APPENDIX 307 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS, SIR JOHN DOUGLAS Frontispiece REGIMENTAL COLOUR To face SIR NEIL DOUGLAS To face 56 LA BELLE ALLIANCE : WHERE THE REGIMENT BIVOUACKED AFTER THE BATTLE OF WATERLOO .. ,, 58 SIR RONALD FERGUSON ,, 86 ILLUSTRATION OF LEVEE DRESS ,, 94 SIR RICHARD TAYLOR ,, 130 COLOURS PRESENTED BY THE QUEEN ,, 152 GENERAL MILLER ,, 154 COLONEL CUMING ,, 160 COLONEL LEITH , 172 KOSHEH FORT ,, 186 REPRESENTATIVE GROUP OF CAMERON HIGHLANDERS 196 PREFACE. WANT has long been felt in the Regiment for some complete history of the 79th Cameron Highlanders down to the present time, and, at the request of Lieutenant-Colonel Everett, D-S.O., and the officers of the Regiment a committee, con- Lieutenant and sisting of Captain T. -

Religion and Politics in New York During the Revolutionary Epoch

RELIGION AND POLITICS IN NEW YORK DURING THE REVOLUTIONARY EPOCH BY MARGARET SCUDDER HALEY A. B. Knox College, 1917. THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1918 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/religionpoliticsOOhale UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THE GRADUATE SCHOOL li^-^j g 1Q1 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY HCfi ^jQ^A SL^LzL^- ENTITLED- BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF T^M^n-^t* c In Charge of Thesis Head of Department Recommendation concurred in* Committee on Final Examination* •"Required for doctor's degree but not for master's 408203 CONTENTS Chapter Page I. Causes of the American Kevolution 1 II. New York city in the latter part of the eighteenth oentury 10 III. The Anglican Church and the devolution. 19 IV. The Presbyterian Church and the devolution 38 V. Other churches and their influence 48 VI . Conclusion 59 Bibliography 60 I. CAUSES OF THE AilERICAN REVOLUTION At the close of a Chapter entitled "Contest for Hew York City," C. H. Van Tyne in his American Revolution makes the state- ment: "So prominent was this religious phase of the struggle that men of limited understanding asserted that the Revolution was a religious war, but they saw only that phase in which they were 1 interested." Certainly no-one would think now of characterizing the revolution as a religious war: yet we know that the various denominations did play an important part, both as factors in the causes of the break with England, and as actual participants in the revolution. -

The History of Cedarville College

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Faculty Books 1966 The iH story of Cedarville College Cleveland McDonald Cedarville University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books Part of the Nonfiction Commons Recommended Citation McDonald, Cleveland, "The iH story of Cedarville College" (1966). Faculty Books. 65. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books/65 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The iH story of Cedarville College Disciplines Creative Writing | Nonfiction Publisher Cedarville College This book is available at DigitalCommons@Cedarville: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books/65 CHAPTER I THE COVENANTERS Covenanters in Scotland. --The story of the Reformed Presby terians who began Cedarville College actually goes back to the Reformation in Scotland where Presbyterianism supplanted Catholicism. Several "covenants" were made during the strug gles against Catholicism and the Church of England so that the Scottish Presbyterians became known as the "covenanters." This was particularly true after the great "National Covenant" of 1638. 1 The Church of Scotland was committed to the great prin ciple "that the Lord Jesus Christ is the sole Head and King of the Church, and hath therein appointed a government distinct from that of the Civil magistrate. "2 When the English attempted to force the Episcopal form of Church doctrine and government upon the Scottish people, they resisted it for decades. The final ten years of bloody persecution and revolution were terminated by the Revolution Settlement of 1688, and by an act of Parliament in 1690 that established Presbyterianism in Scotland.