Chan-Pure Land: an Interpretation of Xu Yun’S (1840-1959) Oral Instructions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zhen Fo Bao Chan Yi Gui True Buddha Repentance Sadhana

真佛寶懺儀軌英文版 Honor the Guru Zhen Fo Bao Chan Yi Gui Treasure the Dharma True Buddha Repentance Sadhana Practice Diligently Transmitted by Living Buddha Lian Sheng Om Guru Lian Sheng Siddhi Hum Published by True Buddha Foundation Translated and sponsored by Ling Shen Ching Tze Temple Ling Shen Ching Tze temple is the first and foremost temple of True Buddha Copyright by True Buddha Foundation, a nonprofit religious School, where Living Buddha Lian Sheng imparted True Buddha Tantra for organization, 2002 many years. Enshrined at the temple are Shakyamuni Buddha, Medicine Buddha, the Five Dhyani Buddhas, Golden Mother, and many beautiful images. General permission is granted to religious and educational institutions for non-commercial reproduction in limited quantities, provided a complete It is located at 17012 N.E. 40th Court, Redmond, WA 98052. Tel: 1-425- reference is made to the source. 882-0916. Group meditation practice is open to public every Saturday at 8 p.m. True Buddha Repentance True Buddha Repentance Refuge and Lineage Empowerment One needs to obtain a lineage empowerment in order to achieve maximum results in his/her tantra practice. One obtains True Buddha lineage by taking refuge in Living Buddha Lian Sheng, Grand Master Lu Sheng Yen, in one of the following ways: In writing Root Guru Mantra Root Guru Mantra (long version) (short version) Perform the remote refuge initiation as follows: Om Ah Hum Om Guru At 7:00 a.m. of either the first or fifteenth of a lunar month, face the Guru Bei Lian Sheng direction of the rising sun. With palms joined, reverently recite the Fourfold Yaho Sasamaha Siddhi Hum Refuge Mantra three times: “namo guru bei, namo buddha ye, namo dharma Lian Sheng ye, namo sangha ye.” Prostrate three times. -

The Three Refuges

The Three Refuges Based on the Work of Venerable Master Chin Kung Translated by Silent Voices Permission for reprinting is granted for non-profit use. Printed 2001 PDF file created by Amitabha Pureland http://www.amtbweb.org Taking Refuge in the Three Jewels We are here today for the Initiation Ceremony of the Three Jewels, which are the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha. I would like to clarify what taking refuge in the Three Jewels means since there have been growing misunderstandings in recent times. These need to be cleared up in order to receive the true benefits. What is Buddhism? Is it a religion? Buddhism is not a religion but rather the most profound and beneficial education based on forty-nine years of Buddha Shakyamuni’s teachings for all sentient- beings. In 1923, Mr. Oyang Jingwu spoke at the University of Zhongshan. The title of his lecture was “Buddhism Is Neither a Religion Nor a Philosophy. It Is a Modern-day Essential.” This lecture was an insightful breakthrough that shook the contempo- rary Chinese Buddhist world. Since Buddhism is an education, we need to understand exactly what its objectives, methods, and principles are. In the Prajna Sutra, we read that its objective is the truth of the Dharma (the causes that initiate all the phenomena of life and the universe). Life refers to us while the universe refers to our living environment. Therefore, the educational content of Buddhism guides us so that we will clearly understand our living environment and ourselves. Today, the formal educational system only partially explains the phenomena of the universe and much of this remains to be proven. -

The Life and Works Oe Han Yongun John Christopher

( 1 ) THE LIFE AND WORKS OE HAN YONGUN Sac. JOHN CHRISTOPHER HOULAHAN. Thesis submitted for the M.Phil degree at The University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies. AUTUMN 1977a ProQuest Number: 10672641 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672641 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 ( 2 ) To The Memory of My Mother. Claire Houlahan who introduced me to hooks* ( 3 ) TABLE OE CONTENTS Abstract ......................... ...... 4 Chapter 1 ................................... 6 2 ............. 19 3 ................................. 34 4 ......... 79 5 .................................... 110 6 138 7 .................................... 185 Conclusion .............................. 251 Appendix ............................. 254 Bibliography............................... • 260 Acknowledgements ................ 268 ( 4 ) Abstract In this thesis I wish to present an ordered account of the life and works of Han Yongun. As a Buddhist priest and philosopher, as a poet and novelist, as an essayist and commentator on his own time the body of his work is many-faceted. This is reflected in the various views of his work. Some critics emphasise his nationalism and the part he played in the independence movements which followed the March 1, 1919 uprising and interpret his work in this light. -

Shaolin Collection - 1

: Shaolin Collection - 1 The History of the Shaolin Temple By: Uwe Schwenk (Ying Zi Long) Shaolin Collection - 1: The History of the Shaolin Temple 1 Introduction This is the first in a series of documents, which are in my opinion considered essential for studying Shaolin Gong Fu. About this Library Most of these documents are translations of historical texts which are just now (2003) beginning to emerge. For this library, only the texts considered as core by the author to the study of Shaolin were selected. While some of the readers might question some of the texts in this collection, please bear in mind, that Shaolin has a different meaning for every person studying the art. Shaolin Collection - 1 One of the most important aspects is history. In the opinion of the author, history defines the future. Therefore, the first document contains the Shaolin History as conveyed to the author by the Da Mo Yuan, and confirmed by Grandmaster Shi Weng Heng and Grand Master Chi Chuan Tsai from Taiwan. Note: The images included are from my private collection and some are courtesy of the Shaolin Perspective website under http://www.russbo.com. Introduction: About this Library 2 The Shaolin Temple History Northern Wei Dynasty 386- 534 The construction of the temple was in honor of the Indian Deravada monk Batuo (Buddhabhadra), he was in 464 one of the first Indian monks that came to China. Buddhabhadra means 'Man with a conscience'. In China he is also known under the name 'Fotuo'. In India he traveled together with 5 others. -

On Faith Or Belief

Research Article Ann Soc Sci Manage Stud Volume 4 Issue 3 - September 2019 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Weicheng Cui DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2019.04.555638 On Faith or Belief Weicheng Cui1,2* 1School of Engineering, Westlake University, China 2Shanghai Engineering Research Center of Hadal Science and Technology, Shanghai Ocean University, China Submission: September 17, 2019; Published: September 30, 2019 *Corresponding author: Weicheng Cui, Chair professor at Westlake University, China and adjunct professor at Shanghai Ocean University, China Abstract Nowadays the opinion of philosophy being useless seems to be very popular in young generation and they will answer you that they do not have a faith if they are asked. As far as the present author is concerned, this view is very incorrect. The power that faith brings to him is enormous. In this paper, the various issues related to faith are discussed. The main points of the paper are: (1) Faith is the same as the body, and everyone has it. The only difference is whether you believe in yourself or others. (2) Since the Hierarch has passed the historical test to be a successful person and he is more reliable to be trusted than yourself. (3) There are three criteria to consider when choosing the Hierarch. The first is whether the life of the Hierarch is what you need; the second is whether the theory of the Hierarch can stand the test of scientific standards; the third is how many great people were cultivated by this philosophy. (4) Five suggestions on how to apply faith to guide your work or life are given. -

The Organ Giving-Away in Mahāyāna Buddhist Perspective

THE ORGAN GIVING-AWAY IN MAHĀYĀNA BUDDHIST PERSPECTIVE BHIKKHUNĪ JING LIU A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Buddhist Studies) Graduate School Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University C.E. 2017 The Organ Giving-Away in Mahāyāna Buddhist Perspective Bhikkhunī Jing Liu A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Buddhist Studies) Graduate School Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University C.E. 2017 (Copyright by Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University) i Thesis Title : The Organ Giving-Away in Mahāyāna Buddhist Perspective Researcher : Bhikkhunī Jing Liu Degree : Master of Arts (Buddhist Studies) Thesis Supervisory Committee : Asst. Prof. Dr. Sanu Mahatthanadull, B.A. (Advertising), M.A. (Buddhist Studies), Ph.D. (Buddhist Studies) : Phramaha Nantakorn Piyabhani, Dr., Pāḷi VIII, B.A. (English), M.A. (Buddhist Studies), Ph.D. (Buddhist Studies) Date of Graduation : March 10, 2018 Abstract This thesis is a research on Organ Giving-Away after death in Mahāyāna Buddhist perspective. There are mainly three objectives in this thesis: (1) to study the definition, types and significance of Giving-Away (dāna) in Mahāyāna scriptures; (2) to study the definition, practice and significance of Organ Giving-Away in Mahāyāna Buddhism; (3) to analyze Organ Giving-Away after death in Mahāyāna Buddhist Perspective. There mainly exists two primary cruxes during the process of this research: (1) the first crux of Organ Giving-Away after death which involves with the problematic definitions for death; (2) the second crux of ii Organ Giving-Away after death which involves with different comprehensions of death and how to take care of death. -

Taking the Three Refuges

The Three Refuges Based on the Work of Venerable Master Chin Kung Translated by Silent Voices Permission for reprinting is granted for non-profit use. Printed 2001 PDF file created by Amitabha Pureland http://www.amtbweb.org.au Taking Refuge in the Three Jewels We are here today for the Initiation Ceremony of the Three Jewels, which are the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha. I would like to clarify what taking refuge in the Three Jewels means since there have been growing misunderstandings in recent times. These need to be cleared up in order to receive the true benefits. What is Buddhism? Is it a religion? Buddhism is not a religion but rather the most profound and beneficial education based on forty-nine years of Buddha Shakyamuni’s teachings for all sentient- beings. In 1923, Mr. Oyang Jingwu spoke at the University of Zhongshan. The title of his lecture was “Buddhism Is Neither a Religion Nor a Philosophy. It Is a Modern-day Essential.” This lecture was an insightful breakthrough that shook the contempo- rary Chinese Buddhist world. Since Buddhism is an education, we need to understand exactly what its objectives, methods, and principles are. In the Prajna Sutra, we read that its objective is the truth of the Dharma (the causes that initiate all the phenomena of life and the universe). Life refers to us while the universe refers to our living environment. Therefore, the educational content of Buddhism guides us so that we will clearly understand our living environment and ourselves. Today, the formal educational system only partially explains the phenomena of the universe and much of this remains to be proven. -

A Journey of Learning and Insight

A Journey of Learning and Insight A Journey of Learning and Insight Chan Master Sheng Yen Dharma Drum Publications Corp. New York & Taipei 2012 DHARMA DRUM PUBLISHING CORPORATION 5F, No.186, Gongguan Road Beitou District, Taipei 11244, Taiwan (R.O.C.) www.ddc.com.tw ©2012 Dharma Drum Publishing Corporation All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. First Edition Printed in Taiwan, February 2012 A JOURNEY OF LEARNING AND INSIGHT by Chan Master Sheng Yen ISBN: 978-957-598-580-6 North America distributor: Chan Meditation Center 90-56 Corona Ave., Elmhurst, NY 11373 Phone: (718) 592-6593 Fax: (718) 592-0717 www.chancenter.org Contents Series Foreword vii Acknowedgements ix Author’s Preface x Chapter 1 Childhood and Youth 1 Chapter 2 Life in the Army 21 Chapter 3 Becoming a Monk and Returning To the Life of a Monk 47 Chapter 4 The Vinaya and the Agamas 57 Chapter 5 Religion and History 69 Chapter 6 Life Studying Abroad 85 Chapter 7 Views from Every Aspect of Japanese Buddhism 95 Chapter 8 My Master’s Thesis 117 Chapter 9 East and West 137 Chapter 10 Traveling and Writing 155 Chapter 11 Standing at the Crossroads Looking at the Street Scenes 175 The Chronicle 190 Also by Chan Master Sheng Yen 192 Series Foreword During his long career as a monk, teacher of Buddadharma, and founder of monasteries, meditation centers, and educational institutions, Master Sheng Yen (1930-2009) was also a very prolific lecturer, scholar, and author. -

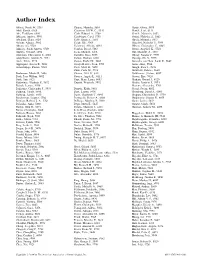

Author Index

Author Index Abbott, Derek W., 5561 Chopra, Manisha, 5610 Garijo, Olivia, 5695 Abdi, Kaveh, 6028 Claassens, Jill W. C., 5540 Gentile, Lori, 6111 Abe, Toshiharu, 6020 Clark, Edward A., 5789 Gentile, Maurizio, 5852 Ablasser, Andrea, 5993 Clayberger, Carol, 5703 Geraci, Nicholas S., 5863 Abraham, Clara, 5924 Cobb, Brian A., 5561 Ghosh, Moumita, 5873 Achour, Adnane, 5802 Colak, Elif, 5963 Giacobbi, Nicholas S., 5933 Akram, Ali, 5520 Colantoni, Alfredo, 6083 Gibson, Christopher C., 6045 Almofty, Sarah Ameen, 5529 Condon, David, 5863 Gierut, Angelica K., 5548 Ameres, Stefanie, 5894 Cook, Michael, 5476 Gill, Michelle A., 5687 Anderson, Christopher S., 6062 Corriden, Ross, 5695 Giltiay, Natalia V., 5789 Andjelkovic, Anuska V., 5974 Cotton, Graham, 6120 Gjoerup, Ole V., 5933 Ando, Yukio, 5720 Cotton, Rachel N., 5863 Gonzales-van Horn, Sarah R., 5687 Applequist, Steven E., 5802 Crespo-Barreto, Juan, 5703 Gotte, Alisa, 5586 Asmawidjaja, Patrick, 5540 Crow, Mary K., 5459 Gough, Peter J., 5476 Cuda, Carla M., 5548 Gouilleux, Fabrice, 5660 Bachmann, Martin F., 5499 Cuenca, Alex G., 6111 Gouttenoire, Je´roˆme, 6037 Back, Jaap Willem, 5802 Cuenca, Angela L., 6111 Gracey, Eric, 5520 Back, Tim, 5821 Cupi, Maria Laura, 6083 Graham, Gerard J., 6120 Badovinac, Vladimir P., 5652 Cypryk, Wojciech, 5952 Grailer, Jamison J., 5974 Baisch, Jeanine, 5586 Granato, Alessandra, 5761 Bakkenist, Christopher J., 5933 Daniels, Keith, 5881 Grassl, Stefan, 6102 Baldwin, Nicole, 5586 Dare, Lauren, 5476 Greenberg, David A., 6009 Baliwag, Jaymie, 6053 Davis, Chadwick T., 6045 Gregory, Christopher D., 5730 Banchereau, Jacques, 5586 DeAngelis, Robert A., 6020 Gudjonsson, Johann E., 6053 Baptista, Barbara J. A., 5761 DeBerge, Matthew P., 5839 Gumz, Janine, 5852 Baranska, Anna, 5830 Degn, Søren E., 5447 Gutzeit, Cindy, 5852 Barber, Glen N., 5571 Delano, Matthew J., 6111 Guzman, Andrew M., 6053 Baron, Christophe, 5660 de la Rosa, Gonzalo, 6062 Bautista, Bianca, 5881 de Oliveira, Sofia, 5710 Haggadone, Mikel D., 5974 Behrendt, Rayk, 5993 De Silva, Thushan, 5802 Haines, G. -

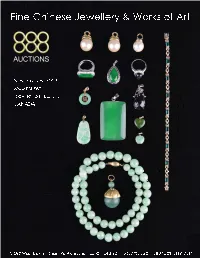

25-COLCATALOG Small.Pdf

888 Auctions 15-280 West Beaver Creek Road Richmond Hill, ON L4B 3Z1 Phone: 905-763-7201 Fax: 905-763-1872 November 8 Auction 30/08/2012-30/08/2013 1 Zun Hu Chinese Watercolour 5 Framed Fan Zeng Chinese Painting Scroll Watercolour Painting Hanging scroll, Chinese watercolour Chinese watercolor on paper of immortal painting, ink and colour on paper; signed and child signed and sealed Fan Zeng. Zun Hu; inscribed and signed with one Framed under glass however it can be artist seal; 98 cm x 32.5 cm shipped frameless. H 73cm, W 53cm 600.00 - 800.00 400.00 - 800.00 2 Zhang Myo Han Chinese Script 6 Guan Shan Yue Chinese Calligraphy Watercolour Painting C. 1989 Hanging scroll, Chinese script calligraphy, Chinese Watercolor on Paper of Cherry ink on paper; signed Zhang Myo Han; Blossoms signed and sealed Guan Shan inscribed and signed with two seals; 91 Yue C. 1989. cm x 31 cm 121.5 cm x 246 cm 400.00 - 800.00 2,500.00 - 4,500.00 3 Framed Chinese Watercolour 7 Fan Zeng (1939-) Chinese Painting on Paper Watercolour Scroll Framed Chinese watercolour painting, ink Chinese watercolour painting, ink and and colour on paper; inscribed and signed colour on paper, signed Fan Zeng with one artist seal; 56 cm x 29 cm (1939-); inscribed and signed with three 200.00 - 300.00 seals; 135.5 cm x 69 cm. Accompanied with certificate of authenticity and published in book 4,000.00 - 8,000.00 4 Chinese Watercolour on Paper 8 Pair of Chinese Watercolor Fan Fan Zeng Guanyin Paintings with Seal Chinese Watercolour on Paper signed Pair of Chinese watercolour fan paintings and sealed Fan Zeng Guanyin. -

Hanshan Deqing on Exile, Zhen Poetry and ‘True’ Chan

Genuine Anguish, Genuine Mind ‘Loyal’ Buddhist Monks, Poetics and Soteriology in Ming-Qing Transition-era Southern China by Corey Lee Bell A THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy in The Faculty of Arts (Asia Institute) The University of Melbourne June 2016 0000-0003-4549-7308 Printed on Archive-quality Paper Abstract The best known genre of Chinese Buddhist poetry is the ‘nature’ or ‘landscape’ poems, which were seen to have religious value because they promoted ‘detachment’ from society and used the tranquillity of a secluded scene to reveal the monastic author’s inner calm. However, during the tumultuous period of dynastic decline and transition in seventeenth- century China, some monks saw religious value in poems that reflected their ‘entanglement’ with a crisis-ridden society, poems that even expressed agitated emotional states prompted by the moral and political disorder of their era. The monks who developed this type of poetry and the literary theory which justified it did so while serving in temples in southern China. These clerics shared an important attribute – they were ‘loyal’ to the ill-fated Ming dynasty (which ruled China until 1644, after which it was replaced by the Manchu Qing), a loyalty that was manifest during the period of the dynasty’s decline and after its fall. A distinctive characteristic of the poems of these monks and of their writings on poetry is that the authors affirmed in different ways the use of poetry to express ‘indignation’ (yuan 怨), particularly indignation at political injustice and social and moral disorder. -

RIGHTVIEW QUARTERLY Dharma in Practice VOLUME ONE, NUMBER 2

RIGHTVIEW QUARTERLY Dharma in Practice VOLUME ONE, NUMBER 2 Master Ji Ru, Editor-in-Chief Xianyang, Editor Carol Corey, Layout and Artwork Will Holcomb, Production Assistance Subscribe at no cost at www.maba-usa.org We welcome letters and comments. Write to [email protected] RIGHTVIEW QUARTERLY is published at no cost to the subscriber by the Mid-America Buddhist Association 299 Heger Lane Augusta, Missouri 63332-1445 USA !e authors of their respective articles retain all copyrights. Our deepest gratitude to Concept Press in New York for their generosity in printing Rightview Quarterly. More artwork by Carol Corey may be seen at www.visualzen.net !e cover picture is a composite of photographs from the Bodhi tree, ficus religiosa, donated to the Mid-America Buddhist Association by Venerable !ubten Chodron. c o n t e n t s 4 Notes and Hopes: An Account of the First Buddhist World Forum by invited guest speaker, Master Ji Ru. 10 Harmony Begins with the Purification of the Mind Chinese Diplomat and World Forum presenter Venerable Jing Yin discusses the origins of harmony. How I Learned to Meditate 14 Novelist Robert Granat tells of his introduction (and resistance) to what has turned into a life-long practice. 18 Inside Out Practice Inmate and Tibetan Buddhist James Hicklin vividly describes his process of transforming shame into the gold of compassion. 22 Practicing with Addiction Buddhism on the path to recovery by Jeffrey Schneider 26 Making Good Use of the "ree Doors of Action Master Jen-chun offers insights into our true body, speech and mind.