The Life and Works Oe Han Yongun John Christopher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proposals for New Biosphere Reserves and Extensions/Modifications/Renaming to Biosphere Reserves That Are Part of the World Network of Biosphere Reserves (Wnbr)

SC-18/CONF.230/8 Paris, 4 June 2018 Original: English UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION International Coordinating Council of the Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Programme Thirtieth session Palembang, South Sumatra Province, Indonesia 23 - 28 July 2018 The Secretariat of the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) does not represent or endorse the accuracy or reliability of any advice, opinion, statement or other information or documentation provided by States to the Secretariat of UNESCO. The publication of any such advice, opinion, statement or other information or documentation on UNESCO’s website and/or on working documents also does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its boundaries. ITEM 10 OF THE PROVISIONAL AGENDA: PROPOSALS FOR NEW BIOSPHERE RESERVES AND EXTENSIONS/MODIFICATIONS/RENAMING TO BIOSPHERE RESERVES THAT ARE PART OF THE WORLD NETWORK OF BIOSPHERE RESERVES (WNBR) 1. Proposals for new biosphere reserves and extensions to biosphere reserves that are already part of the World Network of Biosphere Reserves (WNBR) were considered at the 24rd meeting of the International Advisory Committee for Biosphere Reserves (IACBR), which met at UNESCO Headquarters from 5 to 8 February 2018. 2. The members of the Advisory Committee examined 27 proposals for new biosphere reserves (including one re-submission of a proposal for new biosphere reserve) and three requests for expansion/modification and/or renaming of already existing biosphere reserves and formulated their recommendations regarding specific sites in line with the recommendation categories as follows: 1) Proposals for new biosphere reserves or extensions/modifications/renaming to already existing biosphere reserves recommended for approval: the proposed site is recommended for approval as a biosphere reserve; no additional information is needed. -

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

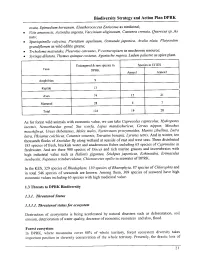

Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan DPRK ovata, Epimedium koreanum, Eleutherococcus Enticosus as medicinal; · Vitis amurensis, Actinidia argenta, Vaccinium uliginosum, Castanea crenata, Querecus sp._As nuts; · Spuriopinella calycina, Pteridium aquilinum, Osmunda japonica, Aralia elata, Platycodon grandifiorum as wild edible greens; · Trcholoma matsutake, 'Pleurotus ostreatus, P. cornucopiaen as mushroom resource; · Syringa dilatata, Thylgus quinque costatus, Agastache rugosa, Ledum palustre as spice plant. Endangered & rare species in Species inCITES Taxa DPRK Annexl Annex2 . Amphibian 9 Reptile 13 Aves 74 15 2 I Mammal 28 4 7 Total 124 19 28 As for forest wild animals with economic value, we can take Caprecolus caprecolus, Hydropotes inermis, Nemorhaedus goral, Sus scorfa, Lepus mandschuricus, Cervus nippon, Moschus moschiferus, Ursus thibetatnus, Meles meles, Nyctereutes procyonoides, Martes zibellina, Lutra lutra, Phsianus colchicus, Coturnix xoturnix, Tetrastes bonasia, Lyrurus tetrix. And in winter, ten thousands flocks of Anatidae fly along wetland at seaside of east and west seas. There distributed 185 species of fresh, brackish water and anadromous fishes including 65 species of Cyprinidae in freshwater. And are there 900 species of Disces and rich marine grasses and invertebrates with high industrial value such as Haliotis gigantea, Stichpus japonicus, Echinoidea, Erimaculus isenbeckii, Neptunus trituberculatus, Chionoecetes opilio in seawater of DPRK. In the KES, 329 species of Rhodophyta, 130 species of Rhaeophyta, 87 species of Chlorophta and in total 546 species of seaweeds are known. Among them, 309 species of seaweed have high economic values including 63 species with high medicinal value. 1.3 Threats to DPRK Biodiversity 1.3. L Threatened Status 1.3.1.1. Threatened status for ecosystem Destruction of ecosystems is being accelerated by natural disasters such as deforestation, soil erosion, deterioration of water quality, decrease of economic resources and also, flood. -

Zhen Fo Bao Chan Yi Gui True Buddha Repentance Sadhana

真佛寶懺儀軌英文版 Honor the Guru Zhen Fo Bao Chan Yi Gui Treasure the Dharma True Buddha Repentance Sadhana Practice Diligently Transmitted by Living Buddha Lian Sheng Om Guru Lian Sheng Siddhi Hum Published by True Buddha Foundation Translated and sponsored by Ling Shen Ching Tze Temple Ling Shen Ching Tze temple is the first and foremost temple of True Buddha Copyright by True Buddha Foundation, a nonprofit religious School, where Living Buddha Lian Sheng imparted True Buddha Tantra for organization, 2002 many years. Enshrined at the temple are Shakyamuni Buddha, Medicine Buddha, the Five Dhyani Buddhas, Golden Mother, and many beautiful images. General permission is granted to religious and educational institutions for non-commercial reproduction in limited quantities, provided a complete It is located at 17012 N.E. 40th Court, Redmond, WA 98052. Tel: 1-425- reference is made to the source. 882-0916. Group meditation practice is open to public every Saturday at 8 p.m. True Buddha Repentance True Buddha Repentance Refuge and Lineage Empowerment One needs to obtain a lineage empowerment in order to achieve maximum results in his/her tantra practice. One obtains True Buddha lineage by taking refuge in Living Buddha Lian Sheng, Grand Master Lu Sheng Yen, in one of the following ways: In writing Root Guru Mantra Root Guru Mantra (long version) (short version) Perform the remote refuge initiation as follows: Om Ah Hum Om Guru At 7:00 a.m. of either the first or fifteenth of a lunar month, face the Guru Bei Lian Sheng direction of the rising sun. With palms joined, reverently recite the Fourfold Yaho Sasamaha Siddhi Hum Refuge Mantra three times: “namo guru bei, namo buddha ye, namo dharma Lian Sheng ye, namo sangha ye.” Prostrate three times. -

The Three Refuges

The Three Refuges Based on the Work of Venerable Master Chin Kung Translated by Silent Voices Permission for reprinting is granted for non-profit use. Printed 2001 PDF file created by Amitabha Pureland http://www.amtbweb.org Taking Refuge in the Three Jewels We are here today for the Initiation Ceremony of the Three Jewels, which are the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha. I would like to clarify what taking refuge in the Three Jewels means since there have been growing misunderstandings in recent times. These need to be cleared up in order to receive the true benefits. What is Buddhism? Is it a religion? Buddhism is not a religion but rather the most profound and beneficial education based on forty-nine years of Buddha Shakyamuni’s teachings for all sentient- beings. In 1923, Mr. Oyang Jingwu spoke at the University of Zhongshan. The title of his lecture was “Buddhism Is Neither a Religion Nor a Philosophy. It Is a Modern-day Essential.” This lecture was an insightful breakthrough that shook the contempo- rary Chinese Buddhist world. Since Buddhism is an education, we need to understand exactly what its objectives, methods, and principles are. In the Prajna Sutra, we read that its objective is the truth of the Dharma (the causes that initiate all the phenomena of life and the universe). Life refers to us while the universe refers to our living environment. Therefore, the educational content of Buddhism guides us so that we will clearly understand our living environment and ourselves. Today, the formal educational system only partially explains the phenomena of the universe and much of this remains to be proven. -

MEMBER REPORT Democratic People's Republic of Korea

MEMBER REPORT Democratic People’s Republic of Korea ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee 15th Integrated Workshop Vietnam 1-2 December 2020 Contents Ⅰ. Overview of tropical cyclones which have affected/impacted member’s area since the last Committee Session 1. Meteorological Assessment 2. Hydrological Assessment 3. Socio-Economic Assessment 4. Regional Cooperation Assessment Ⅱ. Summary of Progress in Priorities supporting Key Result Areas 1. Strengthening Typhoon Analyzing Capacity 2. Improvement of Typhoon Track Forecasting 3. Continued improvement of TOPS 4. Improvement of Typhoon Information Service 5. Effort for reducing typhoon-related disasters Ⅰ. Overview of tropical cyclones which affected/impacted member’s area since the last Committee Session 1. Meteorological Assessment DPRK is located in monsoon area of East-Asia, and often impacted by typhoon-related disasters. Our country was affected by five typhoons in 2020. Three typhoons affected directly, and two typhoons indirectly. (1) Typhoon ‘HAGPIT’(2004) Typhoon HAGPIT formed over southeastern part of China at 12 UTC on August 1. It continued to move northwestward and landed on china at 18 UTC on August 3 with the Minimum Sea Level Pressure of 975hPa and Maximum Wind Speed of 35m/s, and weakened into a tropical depression at 15 UTC. After whirling, it moved northeastward, and landed around peninsula of RyongYon at 18 UTC on August 5, and continued to pass through the middle part of our country. Under the impact of HAGPIT, accumulated rainfall over several parts of the middle and southern areas of our country including PyongGang, SePo, SinGye, and PyongSan County reached 351-667mm from 4th to 6th August with strong heavy rain, and average precipitation was 171mm nationwide. -

Shaolin Collection - 1

: Shaolin Collection - 1 The History of the Shaolin Temple By: Uwe Schwenk (Ying Zi Long) Shaolin Collection - 1: The History of the Shaolin Temple 1 Introduction This is the first in a series of documents, which are in my opinion considered essential for studying Shaolin Gong Fu. About this Library Most of these documents are translations of historical texts which are just now (2003) beginning to emerge. For this library, only the texts considered as core by the author to the study of Shaolin were selected. While some of the readers might question some of the texts in this collection, please bear in mind, that Shaolin has a different meaning for every person studying the art. Shaolin Collection - 1 One of the most important aspects is history. In the opinion of the author, history defines the future. Therefore, the first document contains the Shaolin History as conveyed to the author by the Da Mo Yuan, and confirmed by Grandmaster Shi Weng Heng and Grand Master Chi Chuan Tsai from Taiwan. Note: The images included are from my private collection and some are courtesy of the Shaolin Perspective website under http://www.russbo.com. Introduction: About this Library 2 The Shaolin Temple History Northern Wei Dynasty 386- 534 The construction of the temple was in honor of the Indian Deravada monk Batuo (Buddhabhadra), he was in 464 one of the first Indian monks that came to China. Buddhabhadra means 'Man with a conscience'. In China he is also known under the name 'Fotuo'. In India he traveled together with 5 others. -

On Faith Or Belief

Research Article Ann Soc Sci Manage Stud Volume 4 Issue 3 - September 2019 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Weicheng Cui DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2019.04.555638 On Faith or Belief Weicheng Cui1,2* 1School of Engineering, Westlake University, China 2Shanghai Engineering Research Center of Hadal Science and Technology, Shanghai Ocean University, China Submission: September 17, 2019; Published: September 30, 2019 *Corresponding author: Weicheng Cui, Chair professor at Westlake University, China and adjunct professor at Shanghai Ocean University, China Abstract Nowadays the opinion of philosophy being useless seems to be very popular in young generation and they will answer you that they do not have a faith if they are asked. As far as the present author is concerned, this view is very incorrect. The power that faith brings to him is enormous. In this paper, the various issues related to faith are discussed. The main points of the paper are: (1) Faith is the same as the body, and everyone has it. The only difference is whether you believe in yourself or others. (2) Since the Hierarch has passed the historical test to be a successful person and he is more reliable to be trusted than yourself. (3) There are three criteria to consider when choosing the Hierarch. The first is whether the life of the Hierarch is what you need; the second is whether the theory of the Hierarch can stand the test of scientific standards; the third is how many great people were cultivated by this philosophy. (4) Five suggestions on how to apply faith to guide your work or life are given. -

Academic Paper Series

Academic Paper Series September 2007. Volume 2. No 9 Disaster Management and Institutional Change in the DPRK: Trends in the Songun Era by Alexandre Y. Mansourov One cannot enter the same river twice. Every time one looks ment precipitated by abandonment by strategic allies in at North Korea, on the surface it appears boringly the same. 1990–92; the virtual shutdown of foreign trade and the ensu- Its life fl ows in the same predictable direction, accelerat- ing macroeconomic collapse of the fi rst half of the 1990s; ing at narrow rapids in well known locations that shake up the death of the nation’s founding father, Kim Il-sung, and internal stability and generate international agitation. Once the subsequent regime legitimacy crisis in the mid-1990s; these easily identifi able but hard to overcome bottlenecks the government’s failure to deliver basic services that led to are cleared, the stream of life fl attens, slows, and returns a mass exodus of starving and disaffected people to China to the acceptable order. One can detect the signs of some in the late 1990s; and the nuclear crisis of 2002 resulting in subterranean trends—economic, social, demographic, po- increased international sanctions and isolation. litical, and cultural trends—shaping the direction and pace of life in the country and affecting its relationships with the In addition, the country suffered from the natural disasters outside world. Interpretation of these trends is subjective, of 1995–97 that caused countless deaths from famine and and frame of reference is important: neither demonization enormous infrastructure damage. -

Chan-Pure Land: an Interpretation of Xu Yun’S (1840-1959) Oral Instructions

Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal (2011, 24:105-120) Taipei: Chung-Hwa Institute of Buddhist Studies 中華佛學學報第二十四期 頁105-120 (民國一百年),臺北:中華佛學研究所 ISSN:1017-7132 Chan-Pure Land: An Interpretation of Xu Yun’s (1840-1959) Oral Instructions Damian John Gauci The University of Melbourne Abstract Pure Land and Chan have typically been acknowledged as the two remaining poles of Chinese Buddhism. Pure Land practitioners revere Amitabha Buddha and seek not nirvana but rebirth in the Land of Bliss (jile shijie 極樂世界). Enlightenment is thereby conferred in another time and through another power (i.e. the vows of Amitabha). No more is there retrogression on the path, and the devotee can place all his efforts toward the realization of Buddhahood. By way of comparison, Chan accentuates sudden awakening, advocating the completeness of human capacities and directly pointing to the mind itself. Whereas Pure Land calls upon faith, vows and practice (xin, yuan, xing 信、願、行), Chan asserts the sealing of mind to mind, a ‘transmission outside the teaching.’ The remarkable disparity between the two led to Pure Land philosophy and devotion solidifying “into a carefully-defined and narrowly conceived sectarian movement which claimed to be the only effective method and all-sufficient source of salvation for everyone.” Although this movement dissolved into the very vitality of Chinese Buddhism, debate has, contrary to popular opinion, remained alive and even been revived again in contemporary Chinese Buddhism. It is the aim of the paper to explore this continued debate by focusing on the teachings and advice of Xu Yun 虛雲 as one of the many figures promoting dialectical harmony and understanding. -

The Organ Giving-Away in Mahāyāna Buddhist Perspective

THE ORGAN GIVING-AWAY IN MAHĀYĀNA BUDDHIST PERSPECTIVE BHIKKHUNĪ JING LIU A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Buddhist Studies) Graduate School Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University C.E. 2017 The Organ Giving-Away in Mahāyāna Buddhist Perspective Bhikkhunī Jing Liu A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Buddhist Studies) Graduate School Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University C.E. 2017 (Copyright by Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University) i Thesis Title : The Organ Giving-Away in Mahāyāna Buddhist Perspective Researcher : Bhikkhunī Jing Liu Degree : Master of Arts (Buddhist Studies) Thesis Supervisory Committee : Asst. Prof. Dr. Sanu Mahatthanadull, B.A. (Advertising), M.A. (Buddhist Studies), Ph.D. (Buddhist Studies) : Phramaha Nantakorn Piyabhani, Dr., Pāḷi VIII, B.A. (English), M.A. (Buddhist Studies), Ph.D. (Buddhist Studies) Date of Graduation : March 10, 2018 Abstract This thesis is a research on Organ Giving-Away after death in Mahāyāna Buddhist perspective. There are mainly three objectives in this thesis: (1) to study the definition, types and significance of Giving-Away (dāna) in Mahāyāna scriptures; (2) to study the definition, practice and significance of Organ Giving-Away in Mahāyāna Buddhism; (3) to analyze Organ Giving-Away after death in Mahāyāna Buddhist Perspective. There mainly exists two primary cruxes during the process of this research: (1) the first crux of Organ Giving-Away after death which involves with the problematic definitions for death; (2) the second crux of ii Organ Giving-Away after death which involves with different comprehensions of death and how to take care of death. -

Taking the Three Refuges

The Three Refuges Based on the Work of Venerable Master Chin Kung Translated by Silent Voices Permission for reprinting is granted for non-profit use. Printed 2001 PDF file created by Amitabha Pureland http://www.amtbweb.org.au Taking Refuge in the Three Jewels We are here today for the Initiation Ceremony of the Three Jewels, which are the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha. I would like to clarify what taking refuge in the Three Jewels means since there have been growing misunderstandings in recent times. These need to be cleared up in order to receive the true benefits. What is Buddhism? Is it a religion? Buddhism is not a religion but rather the most profound and beneficial education based on forty-nine years of Buddha Shakyamuni’s teachings for all sentient- beings. In 1923, Mr. Oyang Jingwu spoke at the University of Zhongshan. The title of his lecture was “Buddhism Is Neither a Religion Nor a Philosophy. It Is a Modern-day Essential.” This lecture was an insightful breakthrough that shook the contempo- rary Chinese Buddhist world. Since Buddhism is an education, we need to understand exactly what its objectives, methods, and principles are. In the Prajna Sutra, we read that its objective is the truth of the Dharma (the causes that initiate all the phenomena of life and the universe). Life refers to us while the universe refers to our living environment. Therefore, the educational content of Buddhism guides us so that we will clearly understand our living environment and ourselves. Today, the formal educational system only partially explains the phenomena of the universe and much of this remains to be proven. -

The Wonsan–Mt. Kumgang International Tourist Zone

Trade & investment options in North Korea The Wonsan–Mt. Kumgang International Tourist Zone Rotterdam, June 2016 The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, also known as North Korea) finds itself at a new era of international economic cooperation, and it especially welcomes business with Europe. It is offering various products and services to export markets, while it is also in need for foreign investments. There are several sectors, including energy, agro business, shipbuilding, fishing, logistics, garments, tourism, animation and Information Technology, that can be considered for trade and investment. the new airport terminal of Pyongyang The Korean government is trying to attract a larger number of foreign tourists. There are several investment opportunities in the field of tourism, and an example is the the Wonsan – Mt. Kumgang International Tourist Zone. This zone includes areas of Wonsan, the Masikryong Ski Resort, Ullim Falls, Sokwang Temple, Thongchon and Mt. Kumgang. An introduction into the various investment projects related to this tourist zone is presented below; it is compiled by the Wonsan Zone Development Corporation of DPRK. We can be contacted in case you are interested in exploring this project in more detail. It is also possible for us to arrange investor visits to the Wonsan-Kumgang International Tourist Zone (we organise business missions to DPRK on a regular basis). For information Established in 1995, GPI Consultancy is a specialized Dutch consultancy firm in the field of offshore sourcing. It is involved in business missions to various Asian countries, including North Korea. For companies interested in working with North Korea, one of the immediate challenges is finding a suitable business partner, since collecting information is not easy.