The Sociology of Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Methodological Transactionalism and the Sociology of Education Daniel A

Methodological Transactionalism and the Sociology of Education Daniel A. McFarland, David Diehl and Craig Rawlings (Stanford University) Abstract: The development and spread of research methods in sociology can be understood as a story about the increasing sophistication of tools in order to better answer fundamental disciplinary questions. In this chapter we argue that recent developments, related to both increased computing power and data collection ability along with broader cultural shifts emphasizing interdependencies, have positioned Social Network Analysis (SNA) as a powerful tool for empirically studying the dynamic and processual view of schooling that is at the heart of educational theory. More specifically, we explore how SNA can help us both better understand as well as reconceptualize two central topics in the sociology of education: classroom interaction and status attainment. We conclude with a brief discussion about possible future directions network analysis may take in educational research, positing that it will become an increasingly valuable research approach because our ability to collect streaming behavioral and transactional data is growing rapidly. INTRODUCTION In recent years Social Network Analysis (SNA) has become increasingly common in numerous sociological sub-disciplines, the result being a host of innovative research that tackles old and new problems alike. Students of the sociology of knowledge, for example, use networks of journal co-citations as a novel method for tracking the diffusion of new ideas through the academy (e.g., Hargens 2000; Moody 2004). Political sociologists are drawing on SNA to understand the dynamics of collective action (Diani 1995; Tarrow 1994). Organizational sociologists use formal and informal work networks to study organizational learning (Hansen 1999; Rawlings et.al. -

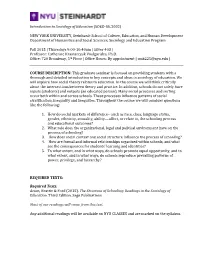

Introduction to Sociology of Education (SOED-GE.2002)

Introduction to Sociology of Education (SOED-GE.2002) NEW YORK UNIVERSITY, Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Sociology and Education Program Fall 2015 | Thursdays 9:00-10:40am | Silver 403 | Professor: Catherine Kramarczuk Voulgarides, Ph.D. Office: 726 Broadway, 5th Floor | Office Hours: By appointment | [email protected] | COURSE DESCRIPTION: This graduate seminar is focused on providing students with a thorough and detailed introduction to key concepts and ideas in sociology of education. We will explore how social theory relates to education. In the course we will think critically about the intersections between theory and practice. In addition, schools do not solely have inputs (students) and outputs (an educated person). Many social processes and sorting occur both within and across schools. These processes influence patterns of social stratification, inequality and inequities. Throughout the course we will consider questions like the following: 1. How do social markers of difference-- such as race, class, language status, gender, ethnicity, sexuality, ability—affect, or relate to, the schooling process and educational outcomes? 2. What role does the organizational, legal and political environment have on the process of schooling? 3. How does social context and social structure influence the process of schooling? 4. How are formal and informal relationships organized within schools, and what are the consequences for students’ learning and identities? 5. To what extent, and in what ways, do schools promote equal opportunity, and to what extent, and in what ways, do schools reproduce prevailing patterns of power, privilege, and hierarchy? REQUIRED TEXTS: Required Texts. -

What Is Sociology of Education? Theoretical Perspectives

CHAPTER 1 What Is Sociology of Education? Theoretical Perspectives whole new perspective on schools and education lies in the study of sociology of education. How sociologists understand education can contribute to informed decision making and A change in educational institutions. Sociologists of education focus on interactions between people, structures that provide recurring organizations, and processes that bring the structures such as schools alive through teaching, learning, and communicating. As one of the major structural parts, or institutions, in society, education is a topic of interest to many sociologists. Some work in university departments teaching sociology or education, others work in government agencies, and still others do research and advise school administrators. Whatever their role, sociologistsdistribute of education provide valu- able insights into the interactions, structures, and processes of educational systems. Sociologists of education examine many parts of educational systems, from interactions, classroom dynamics, and peer groups to school organizations and national and internationalor systems of education. Consider some of the following questions of interest to sociologists of education: What classroom and school settings are best for learning? How do peers affect children’s achievement and ambitions? What classroom structures are most effective for children from different backgrounds? How do schools reflect the neighborhoods in which they are located? Does education “reproduce” the social class of students, and what effect does this have on children’spost, futures? What is the relationship between educa- tion, religion, and political systems? How does access to technology affect students’ learning and prepa- ration for the future? How do nations compare on international educational tests? Is there a global curriculum? These are just a sampling of the many questions that make up the broad mandate for sociology of education, and it is a fascinating one. -

Sociological Background of Adult Education

UNDERSTANDING 5 THE COMMUNITY Sociological Background of Adult and Lifelong Learning SHOBHITA JAIN Structure 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Shift from Psychology-oriented Approach to Sociological Understanding 5.3 Participation from a Social Perspective 5.4 Sociological Approaches 5.4.1 Structural Functionalism 5.4.2 Interpretative Sociology 5.4.3 Theories of Reproduction 5.4.4 Critical Theory of Education 5.5 Conclusion 5.6 Apply What You Have Learnt Learning Objectives After reading Unit 5, it is expected that you would be able to Perceive the process of gradual shifts in understanding adult learning processes Learn about some of the main sociological approaches that are useful in making adult learning more effective Form your own idea of the relationship between adult learning and sociological perspectives. 5. 1 Introduction Unit 3 and Unit 4 have clearly explained learning and social inclusion are high on that education covers all that we current policy agendas. With rapid experience from formal schooling to technological, economic and social the construction of understanding changes in society initial education is through day-to-day life. You may say now regarded as being inadequate in that one’s education begins at birth and terms of preparing individuals with the continues throughout life. Everybody skills and knowledge required for life in receives education from various sources. a knowledge society. As a result it is It is well known that family members and necessary to widen access to adult society influence one’s education and so learning opportunities in order to address it makes sense to discuss sociological the changing needs of society. -

CHAPTER FIVE the SOCIOLOGY of EDUCATION Richard Waller

CHAPTER FIVE THE SOCIOLOGY OF EDUCATION Richard Waller [This chapter is based upon components of my sociology of education teaching at the University of the West of England, some of which was previously taught by my ex- colleague Arthur Baxter, to whom a debt is owed for various materials and ideas expressed here. I do, however, take full responsibility for any errors and omissions!] Learning Objectives By the end of this chapter you should be able to: 1. Explain how sociology can aid our understanding of educational processes and systems 2. Demonstrate an understanding of the key concepts and theoretical approaches in the sociology of education and how they have changed over time 3. Developed an awareness of social context, of social diversity and inequality and their impact on educational processes and outcomes 4. Explain in sociological terms why different social groups achieve differential outcomes from engaging with education 5. Outline an understanding of the nature and appropriate use of research strategies and methods in gaining knowledge in the sociology of education Introduction: Why Study the Sociology of Education? When studying the sociology of education it soon becomes apparent there is an inevitable overlap with most if not all of the disciplinary focus of this book’s other chapters. We cannot examine the sociology of education without understanding its history, and the politics, economics, philosophy and psychology underpinning it. The notion of comparing education systems and peoples’ experiences of engaging with them across societies and within a given society over time is central to this process as well. This overlap is illustrated by reference to some of the key researchers and theorists cited in this chapter. -

Sociology of Education As a New Pedagogical Subdiscipline

*+,'',-./-12,%#2 *!%1#3-4'#"!5%#36-78',3#,'19-#'-:5,2+$;-<+=,'> ?+&#+=+86-+@-A>1&,3#+'- ,%-,-B!$-<!>,8+8#&,=-?1C>#%&#D=#'! !"#$&'()*(+,-.&F$0!1( Studia i szkice z socjologii edukacji [Studies and Essays in Sociology of Education ], Wydawnictwo Akademii Pedagogiki Specjalnej, Warszawa 2015, pages 202 Sociology of education is a branch of sociology, relying on soci- ological theories and fundamental research. It is a relatively young discipline, a discipline in the making, which evolves by referring to and drawing on other scienti"c "elds, such as philosophy, psychol- ogy, social pedagogy, political studies, etc. Considering just these assumptions, it must be emphasized that preparing a publication in the "eld of the sociology of education is a challenge, accessible only to masters of the discipline and the work reviewed in this text is undoubtedly such a case. Aware of the uncharted territory of this "eld of study, the author—Professor Mirosław J. Szymański— assumed the task of casting some light on those research areas that have already been explored at this stage of development of the dis- cipline. In the book, he presents selected issues in the sociology of education—those that are crucial and fundamental. Szymański’s volume consists of ten chapters. &e "rst one, en- titled “Social structure,” presents the problems of social structure in the historical context (making reference to social strati"cation based on caste, estate, and class, theories of social strati"cation, SPI Vol. 20, 2017/1 and empirical evidence of occurrence of social di*erentiation. ISSN 2450-5358 e-ISSN 2450-5366 !&!'()! !"#!$% &is section of the chapter constitutes a perfect introduction to the subjects discussed in chapter two, “Social di*erentiation and educa- tion.” Here the author presents the issues of educational inequali- ties against the background of social conditions. -

Social Darwinism in Anglophone Academic Journals: a Contribution to the History of the Term

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Hertfordshire Research Archive Published in the Journal of Historical Sociology, 17(4), December 2004, pp. 428-63. Social Darwinism in Anglophone Academic Journals: A Contribution to the History of the Term GEOFFREY M. HODGSON ‘Social Darwinism, as almost everyone knows, is a Bad Thing.’ Robert C. Bannister (1979, p. 3) Abstract This essay is a partial history of the term ‘Social Darwinism’. Using large electronic databases, it is shown that the use of the term in leading Anglophone academic journals was rare up to the 1940s. Citations of the term were generally disapproving of the racist or imperialist ideologies with which it was associated. Neither Herbert Spencer nor William Graham Sumner were described as Social Darwinists in this early literature. Talcott Parsons (1932, 1934, 1937) extended the meaning of the term to describe any extensive use of ideas from biology in the social sciences. Subsequently, Richard Hofstadter (1944) gave the use of the term a huge boost, in the context of a global anti-fascist war. ***** A massive 1934 fresco by Diego Rivera in Mexico City is entitled ‘Man at the Crossroads’. To the colorful right of the picture are Diego’s chosen symbols of liberation, including Karl Marx, Vladimir Illych Lenin, Leon Trotsky, several young female athletes and the massed proletariat. To the darker left of the mural are sinister battalions of marching gas-masked soldiers, the ancient statue of a fearsome god, and the seated figure of a bearded Charles Darwin. -

HBEF1103 (M) EDUCATIONAL SOCIOLOGY and PHILOSOPHY Noryati Alias

HBEF1103 (M) EDUCATIONAL SOCIOLOGY AND PHILOSOPHY Noryati Alias Project Directors: Prof Dr Mansor Fadzil Assoc Prof Dr Widad Othman Open University Malaysia Module Writer: Noryati Alias Moderator: Assoc Prof Hazidi Abdul Hamid Developed by: Centre for Instructional Design and Technology Open University Malaysia Printed by: Meteor Doc. Sdn. Bhd. Lot 47-48, Jalan SR 1/9, Seksyen 9, Jalan Serdang Raya, Taman Serdang Raya, 43300 Seri Kembangan, Selangor Darul Ehsan First Printing, September 2009 Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM), September 2009, HBEF1103(M) All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the written permission of the President, Open University Malaysia (OUM). Version September 2009 Table of Contents Course Guide ix-xiv Topic 1 Sociology of Education 1 1.1 Sociology as a Discipline 3 1.2 Primary Social Institutions 5 1.2.1 Family 6 1.2.2 Education 8 1.2.3 Religion 9 1.2.4 Economic and Political Institutions 10 1.3 Sociology of education 11 1.3.1 Definitions 12 1.3.2 Main Areas of Concern 12 1.4 Theoretical Approaches to Sociology of Education 13 1.4.1 Functionalism 13 1.4.2 Conflict Theory 14 1.4.3 The Interpretivistic and Interaction Approach 15 1.4.4 Recent Theories 15 Summary 17 Key Terms 18 References 19 Topic 2 Functions of Education 20 2.1 Functions of Socialisation 22 2.2 Functions of Cultural Transmission 24 2.3 Function of Social Control and Personal Development 25 2.4 Function of Selection and Allocation 27 2.5 Function of Change and Innovation 29 Summary 30 -

PHILOSOPHICAL and SOCIOLOGICAL FOUNDATIONS of EDUCATION Edited by Dr

Edited by: Dr. Kulwinder Pal PHILOSOPHICAL AND SOCIOLOGICAL FOUNDATIONS OF EDUCATION Edited By Dr. Kulwinder Pal Printed by LAXMI PUBLICATIONS (P) LTD. 113, Golden House, Daryaganj, New Delhi-110002 for Lovely Professional University Phagwara SYLLABUS Philosophical and Sociological Foundations of Education Objectives: To understand the importance of various philosophical bases of education. To understand the impact of social theories on education. To relate the trends of social changes, cultural changes and their impact on education. To understand the application of modern science and technological development on social reconstruction. Sr. No. Description 1 Education & Philosophy: Meaning, Relationship, Nature and Scope. Significance of studying Philosophy in Education. Aims of Education: Individual and Social Aims of Education. Functions of Education: Individual, Social, Moral and Aesthetic. 2 School of Philosophical Thoughts: Idealism. School of Philosophical Thoughts: Naturalism. School of philosophical thoughts: Pragmatism. School of philosophical thoughts: Humanism. 3 Indian philosophical thoughts: Sankhya. Indian philosophical thoughts: Vedanta. Indian philosophical thoughts: Buddhism. Indian philosophical thoughts: Jainism. Indian philosophical thoughts: Islam 4 Contribution of Indian thinkers to Educational Thoughts: Mahatma Gandhi and Vivekananda. Contribution of Indian thinkers to Educational Thoughts – Aurobindo and Radhakrishnan 5 Sociology and Education: Concept of Educational Sociology and Sociology of Education. -

Assessment Practices and Their Impact on Home Economics Education In

Assessment practices and their impact on home economics education in Ireland Kathryn McSweeney B.Ed., M. Ed. (T.C.D.) Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Stirling Faculty of Education December 2014 Abstract This study was prompted by an interest in the extent to which the aims of home economics education in Ireland are being served by the assessment carried out at a national level. This interest led to an empirical investigation of key stakeholders’ perceptions of the validity of home economics assessment and a critical evaluation of its impact on teaching and learning. The data collection primarily comprised interviews with a selection of teachers and other key people such as students, teacher educators and professional home economists; and a complementary analysis of curriculum and design of Junior and Leaving Certificate home economics assessments during the period 2005- 2014. The analysis of interview data combined with the curriculum and assessment analyses revealed the compounding impact and washback effect of home economics assessments on student learning experience and outcomes. This impact was reflected in several areas of the findings including an evident satisfaction among the respondents with junior cycle assessment, due to the perceived appropriateness of the assessment design and operational arrangements, and dissatisfaction with curriculum and assessment arrangements at senior cycle as they were considered to be inappropriate and negatively impacting on the quality of learning achieved. The respondents candidly pointed to what they considered to be an acceptance by some teachers of unethical behaviour around the completion of journal tasks. -

Social Class Differences in Family-School Relationships: the Importance of Cultural Capital Author(S): Annette Lareau Source: Sociology of Education, Vol

Social Class Differences in Family-School Relationships: The Importance of Cultural Capital Author(s): Annette Lareau Source: Sociology of Education, Vol. 60, No. 2 (Apr., 1987), pp. 73-85 Published by: American Sociological Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2112583 Accessed: 26/01/2010 16:17 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=asa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Sociological Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Sociology of Education. http://www.jstor.org SOCIAL CLASS DIFFERENCESIN FAMILY-SCHOOLRELATIONSHIPS: THE IMPORTANCEOF CULTURAL CAPITAL ANNETTE LAREAU SouthernIllinois University Sociology of Education 1987, Vol. -

Department of Education

DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION School of Educational Studies (SES) Dr. Harisingh Gour Vishwavidyalaya, Sagar (M.P.) (A CENTRAL UNIVERSITY) Two-Years B.Ed. (Bachelor of Education) B. Ed. CURRICULUM 1 STRUCTURE OF THE B.Ed. CURRICULUM 1. Introduction: Bachelor of Education (B.Ed.) is an undergraduate Professional Degree which prepares students for work as a teacher in schools. The Department board has re‐formulated the B. Ed. programme by diversifying the courses offered and strengthening the content and structure of the programme, in tune with the National Curriculum Framework for Teacher Education (NCFTE), 2014. The diversification is largely done in introducing the advanced courses in education and new specialization courses in emerging areas of the discipline. The structure of the programme is enriched by adding field experiences / specializations in all semesters. 2. Vision: To provide opportunities to young students to shape them as innovative and farsighted teachers who can meet the requirements of global competitive world and contribute to academic excellence. To impart value – based curriculum good academic environment for strengthening faith in humanistic, social and moral values as well as in Indian Cultural heritage and democracy. To create facilities for impairing quality education and grow into a centre of excellence in the field of teacher education. To develop necessary competences in a teacher to have a desire for life-long learning and for reaching the unreached and explore the unexplored. 3. Programme Objectives: To promote capabilities for inculcating national values and goals as mentioned in the constitution of India. To act as agents of modernization and social change. To promote social cohesion, international understanding and protection of human rights and rights of the child.