Distribution Agreement in Presenting This Thesis As A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Play in a Band with 2 Chordal Instruments

FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

Kimmel Center Announces 2019/20 Jazz Season

Tweet it! JUST ANNOUNCED! @KimmelCenter 19/20 #Jazz Season features a fusion of #tradition and #innovation with genre-bending artists, #Grammy Award-winning musicians, iconic artists, and trailblazing new acts! More info @ kimmelcenter.org Press Contact: Lauren Woodard Jessica Christopher 215-790-5835 267-765-3738 [email protected] [email protected] KIMMEL CENTER ANNOUNCES 2019/20 JAZZ SEASON STAR-STUDDED LINEUP INCLUDES MULTI-GRAMMY® AWARD-WINNING CHICK COREA TRILOGY, GENRE-BENDING ARTISTS BLACK VIOLIN AND BÉLA FLECK & THE FLECKTONES, GROUNDBREAKING SOLOISTS, JAZZ GREATS, RISING STARS & MORE! MORE THAN 100,000 HAVE EXPERIENCED JAZZ @ THE KIMMEL ECLECTIC. IMMERSIVE. UNEXPECTED. PACKAGES ON SALE TODAY! FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Philadelphia, PA, April 30, 2019) –– The Kimmel Center Cultural Campus announces its eclectic 2019/20 Jazz Season, featuring powerhouse collaborations, critically-acclaimed musicians, and culturally diverse masters of the craft. Offerings include a fusion of classical compositions with innovative hip-hop sounds, Grammy® Award-winning performers, plus versatile arrangements rooted in tradition. Throughout the season, the varied programming showcases the evolution of jazz – from the genre’s legendary history in Philadelphia to the groundbreaking new artists who continue to pioneer music for future generations. The 2019/20 season will kick off on October 11 with pianist/composer hailed as “the genius of the modern piano,” Marcus Roberts & the Modern Jazz Generation, followed on October 27 -

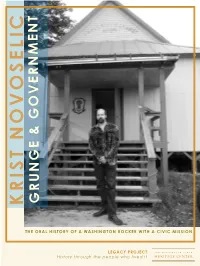

Krist Novoselic

OVERNMENT G & E GRUNG KRIST NOVOSELIC THE ORAL HISTORY OF A WASHINGTON ROCKER WITH A CIVIC MISSION LEGACY PROJECT History through the people who lived it Krist Novoselic Research by John Hughes and Lori Larson Transcripti on by Lori Larson Interviews by John Hughes October 14, 2008 John Hughes: This is October 14, 2008. I’m John Hughes, Chief Oral Historian for the Washington State Legacy Project, with the Offi ce of the Secretary of State. We’re in Deep River, Wash., at the home of Krist Novoselic, a 1984 graduate of Aberdeen High School; a founding member of the band Nirvana with his good friend Kurt Cobain; politi cal acti vist, chairman of the Wahkiakum County Democrati c Party, author, fi lmmaker, photographer, blogger, part-ti me radio host, While doing reseach at the State Archives in 2005, Novoselic volunteer disc jockey, worthy master of the Grays points to Grays River in Wahkiakum County, where he lives. Courtesy Washington State Archives River Grange, gentleman farmer, private pilot, former commercial painter, ex-fast food worker, proud son of Croati a, and an amateur Volkswagen mechanic. Does that prett y well cover it, Krist? Novoselic: And chairman of FairVote to change our democracy. Hughes: You know if you ever decide to run for politi cal offi ce, your life is prett y much an open book. And half of it’s on YouTube, like when you tried for the Guinness Book of World Records bass toss on stage with Nirvana and it hits you on the head, and then Kurt (Cobain) kicked you in the butt . -

Makeup-Hairstyling-2019-V1-Ballot.Pdf

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Hairstyling For A Single-Camera Series A.P. Bio Melvin April 11, 2019 Synopsis Jack's war with his neighbor reaches a turning point when it threatens to ruin a date with Lynette. And when the school photographer ups his rate, Durbin takes school pictures into his own hands. Technical Description Lynette’s hair was flat-ironed straight and styled. Glenn’s hair was blow-dried and styled with pomade. Lyric’s wigs are flat-ironed straight or curled with a marcel iron; a Marie Antoinette wig was created using a ¾” marcel iron and white-color spray. Jean and Paula’s (Paula = set in pin curls) curls were created with a ¾” marcel iron and Redken Hot Sets. Aparna’s hair is blow-dried straight and ends flipped up with a metal round brush. Nancy Martinez, Department Head Hairstylist Kristine Tack, Key Hairstylist American Gods Donar The Great April 14, 2019 Synopsis Shadow and Mr. Wednesday seek out Dvalin to repair the Gungnir spear. But before the dwarf is able to etch the runes of war, he requires a powerful artifact in exchange. On the journey, Wednesday tells Shadow the story of Donar the Great, set in a 1930’s Burlesque Cabaret flashback. Technical Description Mr. Weds slicked for Cabaret and two 1930-40’s inspired styles. Mr. Nancy was finger-waved. Donar wore long and medium lace wigs and a short haircut for time cuts. Columbia wore a lace wig ironed and pin curled for movement. TechBoy wore short lace wig. Showgirls wore wigs and wig caps backstage audience men in feminine styles women in masculine styles. -

AGS Schedule 2019

AGS Schedule 2019 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 7/14 7/15 7/16 7/17 7/18 7/19 7/20 Legislator Day 8:00 AM Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Chambers Cafeteria Chambers Cafeteria Chambers Cafeteria Chambers Cafeteria Chambers Cafeteria Chambers Cafeteria Chambers Cafeteria 8:30 AM 9:00 AM Area II/III - Flood Recovery Field Trip 9:30 AM Area I Area I Area I Area I Area I Meet in M Street Parking Lot at 8:45 am 10:00 AM for Departure at 9:00 am 10:30 AM or John McGraw-Radical? 11:00 AM Area II Area III Area II Area III Area II Militant? Librarianship! Doc Bryan Auditorium 11:30 AM 12:00 PM Lunch Lunch Lunch Lunch Lunch Lunch Lunch Chambers Cafeteria Chambers Cafeteria Chambers Cafeteria Chambers Cafeteria Chambers Cafeteria Chambers Cafeteria Chambers Cafeteria 12:30 PM 1:00 PM 1:30 AM 2:00 PM Area I Area I Area I Area I Area I 2:30 AM Archery Tag Campus Rec Fields 3:00 PM Small Group Meet in Young Small Group Small Group Small Group Small Group 3:30 AM Ballroom 4:00 PM Flood Recovery Field AGS Talks/4:10 AGS Talks/4:10 AGS Talks/4:10 AGS Talks/4:10 Trip Prep 4:30 AM Doc Bryan Auditorium 5:00 PM Dinner Dinner Dinner Dinner Dinner Dinner Dinner Chambers Cafeteria Chambers Cafeteria Chambers Cafeteria Chambers Cafeteria Chambers Cafeteria Chambers Cafeteria Chambers Cafeteria 5:30 AM 6:00 PM Floor Meetings Impact: Luke Dormehl M Street Hall AGS Talks/6:10 AGS Talks/6:10 Witherspoon Aud 6:30 AM Nutt Hall Impact Movie: Blade Runner 7:00 PM Trivia Night Witherspoon Aud Baz-Tech 7:30 -

Kimmel Center Cultural Campus Presents Grammy

Tweet It! 15-time Grammy Award-winning @belafleckbanjo comes to the @KimmelCenter for a groundbreaking quartet performance with @TheFlecktones on 12/3. More info @ Kimmelcenter.org Press Contact: Lauren Woodard Jessica Christopher 215-790-5835 267-765-3738 [email protected] [email protected] KIMMEL CENTER CULTURAL CAMPUS PRESENTS GRAMMY® AWARD-WINNING GROUNDBREAKING QUARTET BÉLA FLECK & THE FLECKTONES FOR THEIR 30TH ANNIVERSARY NORTH AMERICAN TOUR DECEMBER 3, 2019 “…Virtuoso musicianship and mastery of improvisation.” – WXPN “The Flecktones [are as] spry as ever, each at the absolute highest level of craftsmanship on his instrument… the band led the audience through peaks and valleys with astounding proficiency” – GLIDE MAGAZINE “The band is still inscrutable, bordering on mystical.” – CITY NEWSPAPER FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Philadelphia, PA, November 6, 2019) – The Kimmel Center Cultural Campus is proud to present the reunited Béla Fleck & The Flecktones. The original lineup of the quartet, led by 16-time Grammy® Award-winning banjoist/composer Béla Fleck, will grace the Verizon Hall stage on Tuesday, December 3, 2019 at 7:00 p.m. For the performance, Fleck will be joined by Howard Levy on piano and harmonica, percussionist/Drumitarist Roy “Future Man” Wooten, and bassist Victor Wooten. “The revolutionary musicians that comprise Béla Fleck & The Flecktones fuse all manner of genres to create some of the most forward-thinking music of their long, storied careers,” said Anne Ewers, President and CEO of the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts. “Their sound is wholly unique, drawing inspiration from classical and jazz to blues and even Eastern European folk dance. This virtuosic music can be made only with these four individuals. -

Community Formation Among Recent Immigrant Groups in Porto, Portugal

Community Formation among Recent Immigrant Groups in Porto, Portugal By James Beard A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Stanley Brandes, Chair Professor Laura Nader Professor Alex Saragoza Summer 2017 Abstract Community Formation among Recent Immigrant Groups in Porto, Portugal by James Beard Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Professor Stanley Brandes, Chair The last decade has seen a dramatic increase in migration to Europe, primarily by refugees fleeing conflict in the Middle East and Central Asia, but with significant flows of refugees and other migrants from North and sub-Saharan Africa as well. Portugal is not among the primary European destinations for refugees or immigrants; possibly, in part, because there are fewer migrants in Portugal, it is an E.U. country where new arrivals are still met with a degree of enthusiasm. Hard right, anti-immigrant parties—on the rise in other parts of the E.U.— have not gained much traction in Portugal. This work looks at the relative invisibility of immigrants in Porto, the country’s second largest city, which may make those immigrants a less visible target for intolerance and political opportunism, but may also impede a larger, more self- determinant role for immigrants and their communities in greater Portuguese society. A major contributing factor to immigrant invisibility is the absence (outside of Lisbon and southern Portugal) of neighborhoods where African immigrants are concentrated. In Porto, communities do not form around geography; instead, communities form around institutions. -

Central Florida Future, Vol. 25 No. 03, September 1 , 1992

University of Central Florida STARS Central Florida Future University Archives 9-1-1992 Central Florida Future, Vol. 25 No. 03, September 1 , 1992 Part of the Mass Communication Commons, Organizational Communication Commons, Publishing Commons, and the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Central Florida Future by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation "Central Florida Future, Vol. 25 No. 03, September 1 , 1992" (1992). Central Florida Future. 1147. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture/1147 OPINION p. 6 FEATURES p. 9 SPORTSp. 16 Bush discov&rs Rorida Two repeats at 1992 In this issue: Special on!y after seeing polls Jacksonville jazzfest UCF Football Preview entra uture Serving The University of Central Florida Since 1968 Vol. 25, No. 3 TUESDAY September 1, 1992 16 Pages takes effect at UCF Business stµdents only ones affected by new policy. .. at the moment by Ann Marie Sikes Scheuerle, dean of u.:Ildergradu ate studies at the University of STAFF REPORTER South Florida, USF has used The UCF College of Business thedroppolicyforsome lOyears. Administration has officially ini · Scheurele added that the tiated its n~w policy of allowing policy has proven to be very ef professors to drop students from fective for everyone at USF. class if they miss the first day. At USF, the college of busi Stuart Lilie, dean of under ness was also the first college graduate studies, explained that within the university to undergo the only likely exceptions will the policy. -

March 9Th 2001

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Coyote Chronicle (1984-) Arthur E. Nelson University Archives 3-9-2001 March 9th 2001 CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/coyote-chronicle Recommended Citation CSUSB, "March 9th 2001" (2001). Coyote Chronicle (1984-). 496. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/coyote-chronicle/496 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Arthur E. Nelson University Archives at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Coyote Chronicle (1984-) by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A&E A&E A&E A&E^^BFeatures Features Eeatures^^^Coyote Sports Coyote Sports Can You dig it, Swingers New Strike man? for Charity Zone in MLB... on page 7 on page 4 on page 11 THE March 9, 2001 Circulation 5,000 California State University, San Bernardino Issue 17 Volunie34 The Student Zapatistas March Body for Speaks? Rights Referendum: School Chiapas: Indigenous prepares for tuition peoples of Mexico hikes and more con Students pay for the pie but will struggle against effects they get a piece ? struction as measure of globilization, seek Courtesy ofmsnbc.com passes by a majority of for the vote was "the highest retribution Native Chiapas Zapatistas whi want their culture to remain intact the minority of stu voter turn out for a referen tional way of life, their com with the encroachment of dents that voted. dum vote in school history." By Daniel Burruel A total of 1768 people voted Special to the Chronicle munal lands, their right to the Spanish language, against the outside forces By Chris Walenta with 1285 students voting independence, their right to that want to strip them of Executive Editor for the referendum and 483 A war in Mexico is waged defend their traditional way people voting against. -

Innerviews Book

INNERVIEWS: MUSIC WITHOUT BORDERS EXTRAORDINARY CONVERSATIONS WITH EXTRAORDINARY MUSICIANS Anil Prasad ABSTRACT LOGIX BOOKS CARY, NORTH CAROLIna Abstract Logix Books A division of Abstract Logix.com, Inc. 103 Sarabande Drive Cary, North Carolina 27513 USA 919.342.5700 [email protected] www.abstractlogix.com Copyright © 2010 by Anil Prasad ISBN 978-0-578-01518-7 Library of Congress Control Number: Pending Printed in India First Printing, 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without the written permission of the author. Short excerpts may be used without permission for the purpose of a book review. For Grace, Devin and Mimi CONTENTS Acknowledgements vii Foreword by Victor Wooten viii Introduction x Jon Anderson: Harmonic engagement 1 Björk: Channeling thunderstorms 27 Bill Bruford: Storytelling in real time 37 Martin Carthy: Traditional values 51 Stanley Clarke: Back to basics 65 Chuck D: Against the grain 77 Ani DiFranco: Dynamic contrasts 87 v Béla Fleck: Nomadic instincts 99 Michael Hedges: Finding flow 113 Jonas Hellborg: Iconoclastic expressions 125 Leo Kottke: Choice reflections 139 Bill Laswell: Endless infinity 151 John McLaughlin & Zakir Hussain: Remembering Shakti 169 Noa: Universal insights 185 David Sylvian: Leaping into the unknown 201 Tangerine Dream: Sculpting sound 215 David Torn: Mercurial mastery 229 Ralph Towner: Unfolding stories 243 McCoy Tyner: Communicating sensitivity 259 Eberhard Weber: Foreground music 271 Chris Whitley: Melancholic resonance 285 Victor Wooten: Persistence and equality 297 Joe Zawinul: Man of the people 311 Photo Credits 326 Artist Websites 327 About the Author 329 vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people have contributed to Innerviews, both the website and the book, across the years. -

December 1994

Features CHAD SMITH A lot's gone down in the four years since Blood Sugar Sex Magik demanded our collective attention. Now a new Red Hot Chili Peppers album and world tour is around the corner. Chili past, present, and future according to the ever- animated Chad Smith. • Adam Budofsky 20 CHARLI PERSIP Jazz giants like Dizzy Gillespie, Gil Evans, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Billy Eckstein, Archie Shepp, and Eric Dolphy knew very well the value of Charli Persip's talents, even if they eluded the public at large. These days Persip is better than ever—and still pushing the barriers. • Burt Korall 26 INSIDE LP Next stop, Latin Percussion's Thailand factory, where at least one instrument you carry in your gig bag most likely originated. Learn how the world's largest manufacturer of hand percussion instruments gets the job done. 30 • Rick Van Horn Volume 18, Number 12 Cover Photo By Michael Bloom EDUCATION PROFILES EQUIPMENT 52 ROCK'N' 116 UP & COMING JAZZ CLINIC Jay Lane Ghost Notes BY ROBIN TOLLESON BY JOHN XEPOLEAS DEPARTMENTS 78 TEACHERS' FORUM 4 EDITOR'S No Bad Students OVERVIEW BY STEVE SNODGRASS 6 READERS' 88 ROCK PERSPECTIVES PLATFORM 38 PRODUCT Double-Bass-Illusion CLOSE-UP Ostinato 12 ASK A PRO New Drum Workshop BY ROB LEYTHAM Tony Williams, Products Dennis Chambers, BY RICK VAN HORN 92 AROUND and Scott Travis THE WORLD 44 NEW AND Tex-Mex 16 IT'S NOTABLE Border Drumming QUESTIONABLE Highlights From BY MITCH MARINE Summer NAMM '94 94 DRUMLINE BY RICK MATTINGLY 110 UNDERSTANDING RHYTHM 106 CRITIQUE NEWS Basic Reading: Part 1 Thad Jones/Mel -

Béla Fleck & the Flecktones

time o between albums and tours.” tones a “Best Instrumental Composition” Grammy in 1998. Still, the goal of writing a Flecktone 10-string banjo is featured on “Joyful Spring.” For his part, Wooten largely bypassed his famed piece - with Howard - using the unusual 11/16 or 11/8 time signature was, to Fleck’s mind, “unn- assortment of bass eects, noting that the player is what truly matters. Each member had been quite busy with a variety of successful projects – including: Bela’s ished business.” duet collaborations with Chick Corea, a trio with Zakir Hussain and Edgar Meyer (sometimes with “In my mind, the instrument is there to allow the musician to feel something and to the Detroit Symphony) and his expansive adventures in African music, documented in the “When we got together, the 11 idea came back up and Howard came out with something express themselves,” Wooten says. “The music doesn’t come from the instrument, it comes from acclaimed 2009 lm and CD, Throw Down Your Heart. Victor’s solo band tours, camps, recording very Bulgarian,” he says. “I said, ‘It’s really great but it’s really fast and jumpy and complex. What if, the musician. Whatever instrument allows you to express yourself the way you want to at that sessions, clinics and CD releases (including an incredible collaborative project with Stanley Clarke halfway through, we dropped into a gospel 11/4 feel that was so natural, that you didn’t even moment is the one you should play.” and Marcus Miller called SMV, which yielded the album ‘Thunder’), and Future Man's creation of notice it was in 11?’ It was an idea I’d had in my mind for some time, a way of playing something BÉLA FLECK & THE FLECKTONES his amazing Black Mozart project, and continued developement of new instruments.