1 Determinants and Consequences of Car Use Submitted By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walks Programme: July to September 2021

LONDON STROLLERS WALKS PROGRAMME: JULY TO SEPTEMBER 2021 NOTES AND ANNOUNCEMENTS IMPORTANT NOTE REGARDING COVID-19: Following discussions with Ramblers’ Central Office, it has been confirmed that as organized ‘outdoor physical activity events’, Ramblers’ group walks are exempt from other restrictions on social gatherings. This means that group walks in London can continue to go ahead. Each walk is required to meet certain requirements, including maintenance of a register for Test and Trace purposes, and completion of risk assessments. There is no longer a formal upper limit on numbers for walks; however, since Walk Leaders are still expected to enforce social distancing, and given the difficulties of doing this with large numbers, we are continuing to use a compulsory booking system to limit numbers for the time being. Ramblers’ Central Office has published guidance for those wishing to join group walks. Please be sure to read this carefully before going on a walk. It is available on the main Ramblers’ website at www.ramblers.org.uk. The advice may be summarised as: - face masks must be carried and used, for travel to and from a walk on public transport, and in case of an unexpected incident; - appropriate social distancing must be maintained at all times, especially at stiles or gates; - you should consider bringing your own supply of hand sanitiser, and - don’t share food, drink or equipment with others. Some other important points are as follows: 1. BOOKING YOUR PLACE ON A WALK If you would like to join one of the walks listed below, please book a place by following the instructions given below. -

Standard Schedule TR2-58329-Ssa-SL-1-1

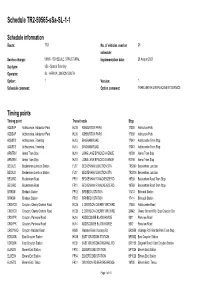

Schedule TR2-59565-sSa-SL-1-1 Schedule information Route: TR2 No. of vehicles used on 25 schedule: Service change: 59565 - SCHEDULE, STRUCTURAL Implementation date: 28 August 2021 Day type: sSa - Special Saturday Operator: SL - ARRIVA LONDON SOUTH Option: 1 Version: 1 Schedule comment: Option comment: TRAMLINK RAIL REPLACEMENT SERVICE Timing points Timing point Transit node Stop ADDSAP Addiscombe, Ashburton Park HJ08 ASHBURTON PARK 17338 Ashburton Park ADDSAP Addiscombe, Ashburton Park HJ08 ASHBURTON PARK 17339 Ashburton Park ADDSTS Addiscombe, Tramstop HJ15 BINGHAM ROAD 17342 Addiscombe Tram Stop ADDSTS Addiscombe, Tramstop HJ15 BINGHAM ROAD 17343 Addiscombe Tram Stop ARNTRM Arena Tram Stop HJ10 LONG LANE BYWOOD AVENUE 18799 Arena Tram Stop ARNTRM Arena Tram Stop HJ10 LONG LANE BYWOOD AVENUE R0746 Arena Tram Stop BECKJS Beckenham Junction Station FJ07 BECKENHAM JUNCTION STN TRS169 Beckenham Junction BECKJS Beckenham Junction Station FJ07 BECKENHAM JUNCTION STN TRS174 Beckenham Junction BECKRD Beckenham Road FP01 BECKENHAM R MACKENZIE RD 19768 Beckenham Road Tram Stop BECKRD Beckenham Road FP01 BECKENHAM R MACKENZIE RD 19769 Beckenham Road Tram Stop BIRKSN Birkbeck Station FP02 BIRKBECK STATION 17413 Birkbeck Station BIRKSN Birkbeck Station FP02 BIRKBECK STATION 17414 Birkbeck Station CROYCO Croydon, Cherry Orchard Road HC25 E CROYDON CHERRY ORCH RD 17348 Addiscombe Road CROYCO Croydon, Cherry Orchard Road HC25 E CROYDON CHERRY ORCH RD 26842 Cherry Orchard Rd / East Croydon Stn CROYPR Croydon, Parkview Road HJ14 ADDISCOMBE BLACK HORSE -

Planning Reports

2. Application No : 03/02718/FULL1 Ward: Kelsey And Eden Park Address : Tesco Stores Ltd Croydon Road Conservation Area:NO Beckenham Kent BR3 4AA OS Grid Ref: E: 535737 N: 168194 Applicant : Tesco Stores Ltd Objections : YES Description of Development: Enlargement of retail store site to include adjacent land to south and site of demolished railway substation, and single storey extensions to store, decked car park over existing car park and extension of surface car park (to increase number of parking spaces from 393 to 564), realignment of access road to service yard, and relocation of service yard, recycling facilities, staff car park and sprinkler tank/pump building 7 0 78 72 PO Pa th FB LB C 5 R 7 33. 4m CF Car 5 Pa rk 4 Pa th H C d n U 3 5 5 2 7 TCB th a P South Norwood Country Park ta ll 2 El me rs En d Ha 9 S 3 b 1 u S Free Ch urch R l C E 1 3 in a r in D ra 8 D 3 34. 4m y 2 d 5 B y B d BM 3 4.9 4m L B d 2 2 r 33. 3m 3 a 1 W 1 1 2 9 7 G 8 O 3 D 1 D 5 A R h SP t D a P R O A 2 D 5 D 0 OA 1 N R O Y D RO 5 C 3 t h 7 k . a n 2 P l i m m ra Su p erst ore T 3 5 El Sub St a 0 2 in ra D El Sub St a F C 2 LB 2 4 2 m .5 5 3 ef D 5 4 a t S b u S l E M 1 P 3 1 1 . -

Programmes and Investment Committee 11 October 2018

Agenda Meeting: Programmes and Investment Committee Date: Thursday 11 October 2018 Time: 10.15am Place: Conference Rooms 1 and 2, Ground Floor, Palestra, 197 Blackfriars Road, London, SE1 8NJ Members Prof Greg Clark CBE (Chair) Dr Alice Maynard CBE Dr Nelson Ogunshakin OBE (Vice-Chair) Dr Nina Skorupska CBE Heidi Alexander Dr Lynn Sloman Ron Kalifa OBE Ben Story Copies of the papers and any attachments are available on tfl.gov.uk How We Are Governed. This meeting will be open to the public, except for where exempt information is being discussed as noted on the agenda. There is access for disabled people and induction loops are available. A guide for the press and public on attending and reporting meetings of local government bodies, including the use of film, photography, social media and other means is available on www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/Openness-in-Meetings.pdf. Further Information If you have questions, would like further information about the meeting or require special facilities please contact: Jamie Mordue, Senior Committee Officer; Tel: 020 7983 5537 Email: [email protected]. For media enquiries please contact the TfL Press Office; telephone: 0845 604 4141; email: [email protected] Howard Carter, General Counsel Wednesday 3 October 2018 Agenda Programmes and Investment Committee Thursday 11 October 2018 1 Apologies for Absence and Chair's Announcements 2 Declarations of Interests General Counsel Members are reminded that any interests in a matter under discussion must be declared at the start of the meeting, or at the commencement of the item of business. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Executive, 28/03/2018 19:00

BROMLEY CIVIC CENTRE, STOCKWELL CLOSE, BROMLEY BRI 3UH TELEPHONE: 020 8464 3333 CONTACT: Graham Walton [email protected] DIRECT LINE: 020 8461 7743 FAX: 020 8290 0608 DATE: 16 March 2018 To: Members of the EXECUTIVE Councillor Colin Smith (Chairman) Councillors Graham Arthur, Peter Fortune, William Huntington-Thresher, Kate Lymer, Peter Morgan and Diane Smith A meeting of the Executive will be held at Bromley Civic Centre on WEDNESDAY 28 MARCH 2018 AT 7.00 PM MARK BOWEN Director of Corporate Services Copies of the documents referred to below can be obtained from http://cds.bromley.gov.uk/ A G E N D A 1 APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE 2 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST 3 QUESTIONS FROM MEMBERS OF THE PUBLIC ATTENDING THE MEETING In accordance with the Council’s Constitution, questions to this Committee must be received in writing 4 working days before the date of the meeting. Therefore please ensure questions are received by the Democratic Services Team by 5pm on Thursday 22nd March 2018. 4 TO CONFIRM THE MINUTES OF THE MEETINGS HELD ON 7TH FEBRUARY 2018 AND 7TH MARCH 2018 (Pages 5 - 38) 5 PROGRESS IN IMPLEMENTING CHILDREN'S SERVICES IMPROVEMENTS - ORAL UPDATE 6 BUDGET MONITORING 2017/18 (Pages 39 - 94) 7 HOMELESSNESS STRATEGY (Pages 95 - 178) 8 BROMLEY DRAFT LOCAL PLAN EXAMINATION - APPROVAL FOR MAIN MODIFICATIONS CONSULTATION (Pages 179 - 206) 9 NATIONAL INCREASE IN PLANNING APPLICATION FEES (Pages 207 - 210) 10 WEST WICKHAM LEISURE CENTRE AND LIBRARY REDEVELOPMENT (Pages 211 - 238) West Wickham Ward 11 NORMAN PARK ATHLETICS TRACK - UPDATE -

Addiscombe – Croydon

1/2 Beckenham – Addiscombe – Croydon 1/2 Mondays to Fridays Beckenham Junction 0454 0554 -- -- 1930 0106 Beckenham Road 0457 0557 -- -- 1933 0109 Avenue Road 0458 0558 -- -- 1934 0110 Birkbeck 0459 0559 -- -- 1935 0111 Harrington Road 0502 Then 0602 -- Then -- 1938 Then 0114 Elmers End Station ↓ every12 ↓ 0609 every12 1933 ↓ every12 ↓ Arena 0505 minutes 0605 0611 minutes 1935 1941 minutes 0117 Woodside 0507 until 0607 0613 oneach 1937 1943 until 0119 Blackhorse Lane 0508 0608 0614 branch 1938 1944 0120 Addiscombe 0510 0610 0616 until 1940 1946 0122 Sandilands 0512 0612 0618 1942 1948 0124 Lebanon Road 0514 0614 0620 1944 1950 0126 East Croydon 0516 0616 0622 1946 1952 0128 1/2 Saturdays Beckenham Junction 0454 0654 -- -- 1806 1812 0112 Beckenham Road 0457 0657 -- -- 1809 1815 0115 Avenue Road 0458 0658 -- -- 1810 1816 0116 Birkbeck 0459 0659 -- -- 1811 1817 0117 Harrington Road 0502 Then 0702 -- Then -- 1814 1820 Then 0120 Elmers End Station ↓ every12 ↓ 0709 every12 1809 ↓ ↓ every12 ↓ Arena 0505 minutes 0705 0711 minutes 1811 1817 1823 minutes 0123 Woodside 0507 until 0707 0713 oneach 1813 1819 1825 until 0125 Blackhorse Lane 0508 0708 0714 branch 1814 1820 1826 0126 Addiscombe 0510 0710 0716 until 1816 1822 1828 0128 Sandilands 0512 0712 0718 1818 1824 1830 0130 Lebanon Road 0514 0714 0720 1820 1826 1832 0132 East Croydon 0516 0716 0722 1822 1828 1834 0134 1/2 Sundays Beckenham Junction 0658 0834 -- 1734 -- 1746 0058 Beckenham Road 0701 0837 -- 1737 -- 1749 0101 Avenue Road 0702 0838 -- 1738 -- 1750 0102 Birkbeck 0703 0839 -- 1739 -- -

London Underground Limited

Background Paper 1 Developing the Network 1 Introduction 1.1 Bus use has increased by over two-thirds since 1999, driven by sustained increases in the size and quality of the network, fares policy and underlying changes in London’s economy. The bus network is constantly evolving as London develops and the needs and aspirations of passengers and other stakeholders change. Enhancements take place not only to the service pattern but across all aspects of the service. • Capacity. The level of bus-km run has increased by around 40 per cent over the same period. Network capacity has increased by a faster rate, by around 55 per cent, with increases in average vehicle size. Additionally, much improved reliability means that more of the scheduled capacity is delivered to passengers. • Reliability. Effective bus contract management, in particular the introduction of Quality Incentive Contracts, has driven a transformation of reliability. This has been supported by bus priority and by the effects of the central London congestion charging scheme. Service control has been made more efficient and effective by iBus, TfL’s automatic vehicle location system. 4.0 3.5 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 Excess Wait Time (mins) 1.0 0.5 0.0 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985/86 1987/88 1989/90 1991/92 1993/94 1995/96 1997/98 1999/00 2001/02 2003/04 2005/06 2007/08 2009/10 2011/12 2013/14 Figure 1: Excess Waiting Time on high-frequency routes – since 1977 • Customer service. All bus drivers must achieve BTEC-certification in customer service and other relevant areas. -

356 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

356 bus time schedule & line map 356 Shirley - Upper Sydenham View In Website Mode The 356 bus line (Shirley - Upper Sydenham) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Shirley: 12:05 AM - 11:35 PM (2) Upper Sydenham: 5:50 AM - 11:55 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 356 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 356 bus arriving. Direction: Shirley 356 bus Time Schedule 50 stops Shirley Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:05 AM - 11:35 PM Monday 12:05 AM - 11:35 PM Sydenham Hill / Kirkdale (MS) Tuesday 12:05 AM - 11:35 PM Droitwich Close (T) Droitwich Close, London Wednesday 12:05 AM - 11:35 PM Canbury Mews (U), Upper Sydenham Thursday 12:05 AM - 11:35 PM Droitwich Close, London Friday 12:05 AM - 11:35 PM Sydenham Hill Estate (V) Saturday 12:05 AM - 11:35 PM Coombe Road (W), Upper Sydenham Bradford Close, London Churchley Road (X) 356 bus Info Direction: Shirley Sydenham / the Woodman (E) Stops: 50 Trip Duration: 47 min Mount Ash Road (F) Line Summary: Sydenham Hill / Kirkdale (MS), Droitwich Close (T), Canbury Mews (U), Upper Heathedge (MR) Sydenham, Sydenham Hill Estate (V), Coombe Road 1 Thorpewood Avenue, London (W), Upper Sydenham, Churchley Road (X), Sydenham / the Woodman (E), Mount Ash Road (F), Sydenham Rise (MZ) Heathedge (MR), Sydenham Rise (MZ), Horniman Sydenham Rise, London Museum (ME), Forest Hill Station / London Road (B), Church Vale (H), Westbourne Drive (N), Siddons Horniman Museum (ME) Road (E), Garlies Road, Adamsrill Road (LT), Bell 100 London Road, London Green / -

Beckenham Junction 2 Croydon - New Addington 3 Wimbledon - Elmers End 4

First Tram Operations Croydon - Elmers End 1 Wimbledon - Beckenham Junction 2 Croydon - New Addington 3 Wimbledon - Elmers End 4 Saturday Ref.No.: 15T Commencing Date: 03/03/2018 Running Number 30 32 21 41 22 19 44 20 24 45 12 26 47 22 27 41 20 29 44 12 30 45 22 32 47 Crew Duty Number 201 202 203 204 205 206 207 208 209 210 211 212 213 205 214 204 208 215 207 211 201 210 205 202 213 Journey/ETM Nos. 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 32 34 36 38 40 42 44 46 48 50 Service No 3 3 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 Wimbledon Station 0556 0611 Dundonald Road 0557 0612 Merton Park 0559 0614 Morden Road 0600 0615 Phipps Bridge 0602 0617 Belgrave Walk 0603 0618 Mitcham 0605 0620 Mitcham Junction 0608 0623 Beddington Lane 0610 0625 Depot East Gate 0413 0428 0441 0443 0450 0456 0458 0505 0511 0513 0520 0526 0528 0541 0556 Therapia Lane 0414 0429 0442 0444 0451 0457 0459 0506 0512 0514 0521 0527 0529 0542 0557 0612 0627 Ampere Way 0415 0430 0443 0445 0452 0458 0500 0507 0513 0515 0522 0528 0530 0543 0558 0613 0628 Waddon Marsh 0417 0432 0445 0447 0454 0500 0502 0509 0515 0517 0524 0530 0532 0545 0600 0615 0630 Wandle Park 0418 0433 0446 0448 0455 0501 0503 0510 0516 0518 0525 0531 0533 0546 0601 0616 0631 Reeves Corner 0420 0435 0448 0450 0457 0503 0505 0512 0518 0520 0527 0533 0535 0548 0603 0618 0633 Church Street 0542 0550 0557 0605 0612 0620 0627 0635 Centrale 0422 0437 0450 0452 0459 0505 0507 0514 0520 0522 0529 0535 0537 0544 0550 0552 0559 0605 0607 0614 0620 0622 0629 0635 0637 West Croydon 0424 0439 0452 0454 0501 0507 -

The Railways (Closure Provisions) (Exemptions) Order 1996

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 1996 No. 1356 TRANSPORT The Railways (Closure Provisions) (Exemptions) Order 1996 Made - - - - 21st May 1996 Laid before Parliament 22nd May 1996 Coming into force - - 24th May 1996 The Secretary of State for Transport, in exercise of the powers conferred by sections 49(2), (4) and (5), 143(4) and 151(5) of the Railways Act 1993(1), and of all other powers enabling him in that behalf, hereby makes the following Order: Citation and commencement 1. This Order may be cited as the Railways (Closure Provisions) (Exemptions) Order 1996 and shall come into force on 24th May 1996. Interpretation 2. In this Order— “the 1993 Act” means the Railways Act 1993; “exempt network” means the network consisting of— (i) the railway line running between Wimbledon Station and West Croydon Station in the London Boroughs of Merton, Sutton and Croydon, through the following stations, namely Merton Park, Morden Road, Mitcham, Beddington Lane, and Waddon Marsh, but excluding the section of track running through Mitcham Junction Station and used for railway services between London and Sutton; (ii) the railway line running between Elmers End Station and Addiscombe Station in the London Boroughs of Croydon and Bromley; and (iii) any installations associated with any of the track comprised in the lines mentioned in sub-paragraphs (i) and (ii) above; “exempt station” means any of the following stations associated with the exempt network, namely Merton Park, Morden Road, Mitcham, Beddington Lane, Waddon Marsh, Addiscombe and Woodside. -

BROMLEY LOCAL HISTORY No.2

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY FOR THE LONDON BOROUGH OF BROMLEY V O L .3. No. 1 S E P T E M B E R 1977 P R IC E 10p Free to Members BROMLEY LOCAL HISTORY No.2 .fter the success of the first publication “ Bromley Local advertising card will be available. The general experience is listory, No. 1.” arrangements are proceeding for the that most agents are only too pleased to take booklets for jcond issue. It is intended that it will be the same size as sale and they do not have to be persuaded. This is a way in ist year’s i.e. 48 pages. Nearly 4,000 copies of the No. 1. which you can help the Society, so please volunteer to take ere sold and it is thought that with more publicity and copies of the booklet and persuade your local bookseller or ilesmanship a greater number can be sold. Members are newsagent to exhibit them in the shop for sale. Offers to sked to help by taking copies to local booksellers and the Hon. Secretary, F.J. Whyler, 163 Tubbenden Lane, :ationers for them to sell. The terms of sale are quite good Orpington. (Farnborough 58679). □ - r py case it is a sale or return basis — and an attractive THE SANDERSONS OF BULLERS REGISTRATION AS AN WOOD, CHISLEHURST DUCATIONAL CHARITY Miss S. Bunnett of Bullers Wood School, St. Nicholas’ .t the annual general meeting held in March, it was Lane, Chislehurst, is collecting information on the family jported that the Committee were of the opinion that the life of John and Agnes Sanderson, who lived in Bullers ociety should be registered as an Educational Charity. -

Investment Programme Report

Transport for London investment programme report Quarter 4 2017/18 About Transport for London (TfL) Contents Part of the Greater London Authority We are moving ahead with many of family led by Mayor of London Sadiq London’s most significant infrastructure Khan, we are the integrated transport projects, using transport to unlock growth. authority responsible for delivering the We are working with partners on major Mayor’s aims for transport. projects like Crossrail 2 and the Bakerloo line extension that will deliver the new 4 Introduction 42 London Underground We have a key role in shaping what homes and jobs London and the UK need. 42 Stations life is like in London, helping to realise We are in the final phases of completing 47 Accessibility the Mayor’s vision for a ‘City for All the Elizabeth line which, when it opens, will 8 Mayor’s Transport Strategy 48 Track renewals Londoners’. We are committed to add 10 per cent to London’s rail capacity. themes in this report 50 Infrastructure renewals creating a fairer, greener, healthier 52 Rolling stock renewals and more prosperous city. The Mayor’s Supporting the delivery of high-density, 54 Signalling and control Transport Strategy sets a target for mixed-use developments that are 11 Safety 80 per cent of all journeys to be made planned around active and sustainable on foot, by cycle or using public travel will ensure that London’s growth 57 Surface transport by 2041. To make this a reality, is good growth. We also use our own 14 Business at a glance 57 Healthy Streets we prioritise health and the quality of land to provide thousands of new 64 Air quality and environment people’s experience in everything we do.