CH 112 Special Assignment #4 Chemistry to Dye For: Part B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Maiwa Guide to NATURAL DYES W H at T H Ey a R E a N D H Ow to U S E T H E M

the maiwa guide to NATURAL DYES WHAT THEY ARE AND HOW TO USE THEM WA L NUT NATURA L I ND IG O MADDER TARA SYM PL O C OS SUMA C SE Q UO I A MAR IG O L D SA FFL OWER B U CK THORN LIVI N G B L UE MYRO B A L AN K AMA L A L A C I ND IG O HENNA H I MA L AYAN RHU B AR B G A LL NUT WE L D P OME G RANATE L O G WOOD EASTERN B RA ZIL WOOD C UT C H C HAMOM IL E ( SA PP ANWOOD ) A LK ANET ON I ON S KI NS OSA G E C HESTNUT C O C H I NEA L Q UE B RA C HO EU P ATOR I UM $1.00 603216 NATURAL DYES WHAT THEY ARE AND HOW TO USE THEM Artisans have added colour to cloth for thousands of years. It is only recently (the first artificial dye was invented in 1857) that the textile industry has turned to synthetic dyes. Today, many craftspeople are rediscovering the joy of achieving colour through the use of renewable, non-toxic, natural sources. Natural dyes are inviting and satisfying to use. Most are familiar substances that will spark creative ideas and widen your view of the world. Try experimenting. Colour can be coaxed from many different sources. Once the cloth or fibre is prepared for dyeing it will soak up the colour, yielding a range of results from deep jew- el-like tones to dusky heathers and pastels. -

Guide to Dyeing Yarn

presents Guide to Dyeing Yarn Learn How to Dye Yarn Using Natural Dyeing Techniques or some of us, the pleasure of using natural dyes is the connection it gives us with the earth, using plants and fungi and minerals from the environment in our Fhandmade projects. Others enjoy the challenge of finding, working with, and sometimes even growing unpredictable materials, then coaxing the desired hues. My favorite reason for using natural dyes is just plain lovely color. Sometimes subtle and always rich, the shades that skilled dyers achieve with natural dyestuffs are heart- breakingly lovely. No matter what inspires you to delve into natural dyes, this free eBook has some- thing for you. If you’re interested in connecting with the earth, follow Lynn Ruggles as she combines her gardening and fiber passions, or join Brighid’s Dyers as they harness alternative energy with solar dyeing. To test and improve your skills, begin with Dag- mar Klos’s thorough instructions. But whatever your reason, be sure to enjoy the range of natural colors on every page. One of Interweave’s oldest publications, Spin.Off inspires spinners to make beautiful yarn and find enchanting ways to use it. In addition to the quarterly magazine, we also host the spinning community spinningdaily.com, complete with blogs, forums, and free patterns. In our video workshop series, the living treasures of the spinning world share their knowledge. We’re devoted to bringing you the best spinning teachers, newest spinning techniques, and most inspiring ideas—right to your mailbox, your computer, and your very fingertips. -

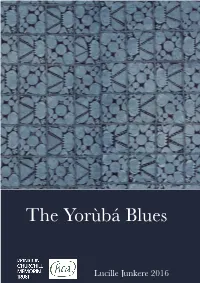

WCMT Report a Lucille Junkere

The Yorùbá Blues Lucille Junkere 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 2 UK Collections 3 Lagos 5 Abẹòḱ uta 9 Ìbàdàn 14 Dyeing 15 Osogbo 17 Recommendations 19 References 20 Picture Credits 23 Glossary 25 Acknowledgments The Winston Churchill Memorial Trust and the Heritage Crafts Association for the wonderful opportunity to travel to Nigeria to study Yorùbá indigenous àdìrẹ making. Nigeria Chief (Mrs) Nike and her husband Reuban Okundaye for their generous support and encouragement and staff from Nike Art Gallery and Foundation in Lagos. Professor Olusẹgun Okẹ, Doig Simmonds (UK) and Pat Oyelọla editors of Adire Cloth in Nigeria Àdire makers and dyers including Gàníyù Kàrímù , Baba Salieu, Jumoke Maryam Akinyemi, and Baba alaro from Àdùnní Art, Olalekan Adegun Adesoye and apprentice from Ade Omo Ade Art Gallery and staff, teachers and students from the Nike Center for Art and Culture, Òṣogbo Mayowa Kila for Yorùbá translation Curator Ige Akintunde Olatunji and colleagues from the National Museum of Abeokuta Professors Oladele O. Layiwola and Ohioma Ifounu Pogoson and Oluwatoyin A. Odeku from the Institute of African Studies My wonderful Lagos hosts Baba Winfield, Chef Craig and Ms Carmen. UK Yorùbá language classes Ṣola Otiti Staff and curators of the UK Museum African collections for supporting my research visits. The British Museum, The Horniman Museum, The Economic Botany Collection at Kew Gardens, The Pitt Rivers Museum, The Royal Albert Memorial Museum, The Victoria and Albert Museum Duncan Clarke from Adire African Textiles 1 Introduction Before the development of synthetic dyes in The literal translation of the word àdìrẹ is the mid-nineteenth century, dyes were to tie and to dye, a description of the extracted from natural sources such as original and oldest resist pattern making plants, animals and minerals (Areo and technique. -

Laboratory Guide Industrial Chemistry

LA BO R A T O R Y G U I D E IN DU ST R IA L C H EMIST RY BY R ALLEN ROGE S, PH . D. I STR CTOR IN INDUSTRIAL CHEH ISTRY PRATT INSTITU TE OOKL N U , , B R YN ; I EHB EE AKERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY; SOCIETY OF CH MCAL INDUSTRY; AHE RICAN LEATH ER CHEMI STS ASSOCIATION N E W Y O R K D N O T R N D C MP N Y . V A N S A O A E ' 23 MURRAY AND 1 908 27 WA RR N Srs . o ri ht 1 08 C py g , 9 D AN N TRAND MP Y BY . V OS CO AN The filimflon Pre ss N w ood Mass . FACT S WHICH SHOULD BE REMEMBERED l Do r igh t and you will be succe ssfu . k wh i h i for u n d do i with smil c o . Do th e tas s se t be e y , a t a e im r r Do not be a t e se ve . ’ Do not use your ne igh bor s standa rd solution for accurate de te r i m nations . D n rr w r o ot bo o appa atus . Ke e our de sk and a aratus cle an if ou h o e to obta in satis p y pp , y p r facto y re sults . Alwa h ow l d n e in o r de sk and use th e m wh e n ys ave a t e an spo g y u , r h d you le a ve fo t e ay . -

Mordanting Methods for Dyeing Cotton Fabrics with Dye from Albizia Coriaria Plant Species

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 4, Issue 10, October 2014 1 ISSN 2250-3153 Mordanting Methods for Dyeing Cotton Fabrics with Dye from Albizia Coriaria Plant Species Loum Janani *, Lukyambuzi Hillary **, Kodi Phillips *** * Lecturer in Department of Textile and Ginning Engineering, Busitema University, PO Box, 236, Tororo, Uganda. ** Department of Textile and Ginning Engineering, Busitema University, PO Box, 236, Tororo, Uganda. *** Department of Chemistry, Kyambogo University, PO Box 1, Kampala Abstract- The study investigated the effects of different methods Most natural dyes need chemical species called mordants of application of selected mordants on dyeing woven cotton with for binding the dye to fabrics to improve color fastness. dyes from the stem bark of Albizia coriaria. The methods of Mordants help in binding of dyes to fabric by forming a chemical application of mordants used includes; pre-mordanting, bridge from dye to fiber thus improving the staining ability of a simultaneous mordanting and post-mordanting. The effects on dye with increasing its fastness properties [7]. The color fastness cotton analyzed are color fastness to; light, washing, wet and dry and characteristics of natural dyes on fabrics are influenced by rubbing and color characteristics on CIELab color coordinates. the mordanting method applied whose effects vary with the Aqueous extraction method was used to extract the dye. Some source of the dye. selected mordants were used for dyeing viz; alum, ferrous In Uganda, great potential exists for natural dyes from dye- sulphate1, and iron water. In the control dyeing without the use yielding plants. In a recent study, it has been reported that several of mordants, very good fastness were registered with the plant species in Uganda possess dye-yielding properties [8]. -

Proposal Penelitian

DEGRADASI FOTOKATALITIK ZAT WARNA REMAZOL RED RB 133 DALAM SISTEM TiO2 SUSPENSI NATALIA GUNADI 0304030359 UNIVERSITAS INDONESIA FAKULTAS MATEMATIKA DAN ILMU PENGETAHUAN ALAM DEPARTEMEN KIMIA DEPOK 2008 Degradasi fotokatalitik..., Natalia Gunadi, FMIPA UI, 2008 DEGRADASI FOTOKATALITIK ZAT WARNA REMAZOL RED RB 133 DALAM SISTEM TIO2 SUSPENSI Skripsi diajukan sebagai salah satu syarat untuk memperoleh gelar Sarjana Sains Oleh: NATALIA GUNADI 0304030359 DEPOK 2008 Degradasi fotokatalitik..., Natalia Gunadi, FMIPA UI, 2008 SKRIPSI : DEGRADASI FOTOKATALITIK ZAT WARNA REMAZOL RED RB 133 DALAM SISTEM TIO2 SUSPENSI NAMA : NATALIA GUNADI NPM : 0304030359 SKRIPSI INI TELAH DIPERIKSA DAN DISETUJUI DEPOK, JULI 2008 Dr. YOKI YULIZAR Dr. RIDLA BAKRI, M.Phil. PEMBIMBING I PEMBIMBING II Tanggal lulus Ujian Sidang Sarjana : Penguji I : Penguji II : Penguji III : Degradasi fotokatalitik..., Natalia Gunadi, FMIPA UI, 2008 ABSTRAK Fotokatalisis dengan TiO2 -UV dapat digunakan untuk menurunkan kadar limbah zat warna dalam suatu badan air. Pada penelitian ini dilakukan degradasi fotokatalitik zat warna Remazol Red RB 133 dalam sistem TiO2 suspensi. Uji degradasi dilakukan pada kondisi kontrol, fotolisis, katalisis, dan fotokatalisis untuk mengetahui pengaruh kondisi reaksi terhadap proses degradasi. Sedangkan pengukuran lainnya dilakukan dengan memvariasikan jumlah TiO2, waktu irradiasi, pH dan konsentrasi larutan zat warna. Hasil maksimal diperoleh saat kondisi fotokatalisis menggunakan 200 mg TiO2; pH 3,13; waktu irradiasi selama 120 menit dan konsentrasi larutan zat warna sebesar 2,52x10-5 M dengan persentase degradasi mencapai 100%. Persentase penurunan COD mencapai 10,95% untuk degradasi fotokatalitik pada pH 6,90. Kinetika reaksi fotodegradasi ditentukan dengan metode orde satu, Langmuir-Hinshelwood (L-H), dan initial rate. Kata kunci: Fotokatalisis; TiO2; Remazol Red RB 133 xvi + 105 hlm.; gbr.; tab.; lamp. -

2016 Proceedings Vancouver, British Columbia

Vancouver, British Columbia 2016 Proceedings Title: Primaries in Square Denise Green, Cornell University Keywords: Sustainability, Textile Innovation, Couture Techniques Measurements: Waist: 28” Bust: 34” Hip: 36” Primaries in Square is a dress and cloak ensemble that uses simple shapes and minimal-waste pattern cutting to sustainably celebrate the productive tension between control and chaos. The primaries -- blue, yellow and red -- were created using Indigofera tinctoria (indigo), Curcuma longa (turmeric), and Rubia tinctorum (common madder) and applied to silk charmeuse and dupioni (both 19mm), with the latter two dyes applied to silk mordanted with aluminum potassium sulfate at 6% owf. The design pays homage to complex simplicity by using primary colors derived from plants and applying colors to simple shapes like squares and rectangles. Stream of consciousness surface design was created through batik “action painting” and combined with mokume shibori, a more controlled stitched resist technique. Surface design techniques disrupt basic shapes and colors to add aesthetic complexity and to conceptually remind us of the water used and often abused in textile production. As apparel designers, we often begin design construction by cutting pattern pieces from rectangular fabric. Likewise, we often create specific colors using some combination of primary colors. Primaries in Square is an experiment in retaining the “starting points”—that is, the rectangular shapes and the primary colors. By using rectangles, this design minimizes wasted fabric and by using primaries from natural sources, we are forced to reconsider certain assumptions about natural dyes as “drab.” The luxurious drape of silk charmeuse forces the rectangular shape to take on the movement and silhouette of the human body animating the garment. -

Effects of Dye Substantivity in Dyeing Cotton Width Reactive Dyes

i i FIRST PLACE WINNER: Quebec Section Effects of Dye Substantiv ity in Dyeing Cotton with Reactiv :?Dyes n dyeing cotton with fiber reactive the material. The dyebath exhaustion at In almost any range of commercial 1 dyes, the addition of alkali to the the end of this phase is called the primary reactive dyes, there is a graduation of dyebath not only promotes formation of exhaustion. substantivity from very low to medium, or the covalent bond between the dye and the 0 The fixation phase. This begins when even quite high substantivity, particularly cellulose but also causes hydrolysis of the alkali is added to the dyebath to raise the in the presence of salt. The dyer is thus reactive group of the dye. Unfixed hydro- pH to the point where the dissociated faced with the problem of deciding how lyzed dye remaining in the fabric after the hydroxyl groups of the cellulose begin to severe the washing conditions should be dyeing process must be removed by wash- react with the dye. Migration of the fixed for removal of unfixed dye from the ing, otherwise the optimal fastness to dye is impossible. During this stage, more material since he must decrease the resid- washing and crocking of the final fabric dye is absorbed from the solution and ual amount to the level that his client is will not be realized. The batch dyeing reacts with the cellulose. The exhaustion satisfied with the fastness properties of the process thus consists of three stages: of the dyebath at the end of the process is final product. -

2016Proceedings

2016 Proceedings Vancouver, British Columbia Title: Resist Denise Nicole Green, Cornell University Keywords: Textile Innovation, Sustainability, Couture Techniques Measurements: Bust: 34” Waist: 28” Hips: 36” Resist interrogates the productive tension of dye penetratio n using clamped shibori, batik and natural dyeing techniques on silk dupioni and charmeus e. The design is dynamic and changes with wear and exposure to light, washing, and the moving body by using two natural dy es known for poor fastness of color - turmeric ( Curcuma longa ) and indigo ( Indigofera tinctoria ) – in addition to madder root ( Rubia tinctorum ). Aluminum sulfate at 6% owf was used as a mordanting agent for turmeric and ma dder dyes. While mordanting preserves some fastness of color, the blues and yellows in the jacket/dress ensemb le will slowly fade into subdued colors that remain luminescent because of the shape of the silk fiber. In imagining sustainable futures, my design research asks: What new aesthetic possibilities arise when we re-think attachment s to constancy of color and embrace the spontaneity of degradation, change and metamorphosis? While natural dyeing is a newly growing area of interest among hobbyists and fashion/textile designers in Europe and North America, it has been practiced for thousands of years in civilizations acr oss the globe. For example, archaeologists have found evidence of natural colorants a nd mordants in textile fragments from the Harappan Period of the Indus Valley Civilization (2600 – 1900 BC) (Kenoye r 2004). Other naturally dyed textiles have been recovered from Egyptian tombs and in more recent history na tural dye methods were highly developed in places like India where textiles were an important trade material through the late 18 th century (Wendt 2009). -

Fastness Properties of Silk Fabric Dyed with Extraction of Psoralea Corylifolia (L) Vidhya

International Journal on Textile Engineering and Processes ISSN 2395-3578 Vol. 3, Issue 3 July 2017 Fastness Properties of Silk Fabric Dyed with Extraction of Psoralea Corylifolia (L) Vidhya. R, K.N. Ninge Gowda Department of Apparel Technology and Management, Bangalore University, Bengaluru, India, [email protected] Abstract This paper concerns with extraction of natural dye from seeds of Psoralea Corylifolia L and used to dye silk fabric. In order to optimize the dyeing conditions for obtaining a good performance of the dyed material it was necessary to optimize the various aqueous dye extraction and dyeing conditions such pH, temperature and duration. The study also investigated the effects of different methods of application of selected mordants like alum and myrobolan were used for dyeing on plain woven silk fabric. The techniques of application of mordants used includes; pre-mordanting, simultaneous mordanting and post-mordanting. The effects on silk examined for color fastness to; light, washing, wet and dry rubbing and color characteristics on CIEL ab color coordinates. Very good fastness ratings were registered for washing (4-5), dry rubbing (5), wet rubbing (5) and moderately good fastness for light (2). The natural dye is a substantive dye since it registered very good fastness grades except sunlight without the use of mordants. The use of mordants improved color fastness to light from ratings of (2) to (3/4). However, there was observable effect of mordanting methods with myrobalan when compared to alum. Keywords - Silk, Dyeing, Fastness, Mordanting, Psoralea Corylifolia L I. Introduction Originally, the dyes were made from naturally available pigments mixed with water and oil applied on skin or clothing to decorate. -

Natural Dyes: Extraction and Applications

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2021) 10(01): 1669-1677 International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 10 Number 01 (2021) Journal homepage: http://www.ijcmas.com Review Article https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2021.1001.195 Natural Dyes: Extraction and Applications Lizamoni Chungkrang*, Smita Bhuyan and Ava Rani Phukan Department of Textiles and Apparel Designing, College of Community Science, Assam Agricultural University, Jorhat, Assam, India *Corresponding author ABSTRACT K e yw or ds Coloration, Dyeing, Natural dyes are obtained from natural sources such as vegetable, animal or Extraction, mineral matters. These dyes are generally used in coloration of textiles, Mordant, Natural dye etc. food, cosmetics and drugs. This article attempts to reviews the classification of natural dyes according to the method of application Article Info available natural dye sources, mordant and its classification, different mordanting methods, extraction methods, dyeing methods and advantages Accepted: 12 December 2020 and disadvantages of natural dyes have been discussed. Available Online: 10 January 2021 Introduction German Legislation (Consumer Goods Ordinance). Netherlands followed a ban with Presently there is a great demand for the use effect from August 1, 1996 on similar lines. of natural colours throughout the world due to European Union is likely to impose ban on non-biodegradable and carcinogenic nature these toxic dyes shortly. India has also banned associated with synthetic dyes (Chungkrang the use of specific azo-dyes and under and Bhuyan, 2020). They are not produce any notification ―sufficient legal teeth‖ had been undesired by-products and at the same time given for taking panel action against those they help in regenerating the environment, who use these dyes (Kapoor and therefore natural dyes are the safe dyes Pushpangadan, 2001; Singh et al., 2006). -

Dyeing Studies and Fastness Properties of Brown Naphtoquinone Colorant Extracted from Juglans Regia L on Natural Protein Fiber U

Bukhari et al. Textiles and Clothing Sustainability (2017) 3:3 Textiles and Clothing DOI 10.1186/s40689-016-0025-2 Sustainability RESEARCH Open Access Dyeing studies and fastness properties of brown naphtoquinone colorant extracted from Juglans regia L on natural protein fiber using different metal salt mordants Mohd Nadeem Bukhari1, Shahid-ul-Islam1, Mohd Shabbir1, Luqman Jameel Rather1, Mohd Shahid1, Urvashi Singh1, Mohd Ali Khan2 and Faqeer Mohammad1* Abstract In this study, wool fibers are dyed with a natural colorant extracted from walnut bark in presence and absence of mordants. The effect of aluminum sulfate, ferrous sulfate, and stannous chloride mordants on colorimetric and fastness properties of wool fibers was investigated. Juglone was identified as the main coloring component in walnut bark extract by UV visible and FTIR spectroscopic techniques. The results showed that pretreatment with metallic mordants substantially improved the colorimetric and fastness properties of wool fibers dyed with walnut bark extract. Ferrous sulfate and stannous chloride mordanted wool fibers shows best results than potassium aluminum sulfate mordanted and unmordanted wool fibers. This is ascribed due to strong chelating power of ferrous sulfate and stannous chloride mordants. Keywords: Juglans regia L., Napthoquinone, Dyeing, Wool, Fastness properties Background (Khan et al. 2012; Yusuf et al. 2015), insect repellent (Ali Synthetic colorants in view of cheaper price, wide range et al. 2013), fluorescence (Rather et al. 2015), UV protec- of colors, and considerable improved fastness properties tion (Grifoni et al. 2009; Sun and Tang 2011), and deodor- are extensively used in textile industries for dyeing of izing (Lee et al. 2009).