Primary Care Issues in Patients with Mental Illness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schizophrenia Care Guide

August 2015 CCHCS/DHCS Care Guide: Schizophrenia SUMMARY DECISION SUPPORT PATIENT EDUCATION/SELF MANAGEMENT GOALS ALERTS Minimize frequency and severity of psychotic episodes Suicidal ideation or gestures Encourage medication adherence Abnormal movements Manage medication side effects Delusions Monitor as clinically appropriate Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome Danger to self or others DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA/EVALUATION (PER DSM V) 1. Rule out delirium or other medical illnesses mimicking schizophrenia (see page 5), medications or drugs of abuse causing psychosis (see page 6), other mental illness causes of psychosis, e.g., Bipolar Mania or Depression, Major Depression, PTSD, borderline personality disorder (see page 4). Ideas in patients (even odd ideas) that we disagree with can be learned and are therefore not necessarily signs of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is a world-wide phenomenon that can occur in cultures with widely differing ideas. 2. Diagnosis is made based on the following: (Criteria A and B must be met) A. Two of the following symptoms/signs must be present over much of at least one month (unless treated), with a significant impact on social or occupational functioning, over at least a 6-month period of time: Delusions, Hallucinations, Disorganized Speech, Negative symptoms (social withdrawal, poverty of thought, etc.), severely disorganized or catatonic behavior. B. At least one of the symptoms/signs should be Delusions, Hallucinations, or Disorganized Speech. TREATMENT OPTIONS MEDICATIONS Informed consent for psychotropic -

Inhaled Loxapine Monograph

Inhaled Loxapine Monograph Inhaled Loxapine (ADASUVE) National Drug Monograph February 2015 VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Services, Medical Advisory Panel, and VISN Pharmacist Executives The purpose of VA PBM Services drug monographs is to provide a comprehensive drug review for making formulary decisions. Updates will be made when new clinical data warrant additional formulary discussion. Documents will be placed in the Archive section when the information is deemed to be no longer current. FDA Approval Information Description/Mechanism of Inhaled loxapine is a typical antipsychotic used in the treatment of acute Action agitation associated with schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder in adults. Loxapine’s mechanism of action for reducing agitation in schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder is unknown. Its effects are thought to be mediated through blocking postsynaptic dopamine D2 receptors as well as some activity at the serotonin 5-HT2A receptors. Indication(s) Under Review in Inhaled loxapine is a typical antipsychotic indicated for the acute treatment of this document (may include agitation associated with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder in adults. off label) Off-label use Agitation related to any other cause not due to schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder. Dosage Form(s) Under 10mg oral inhalation using a new STACCATO inhaler device. Review REMS REMS No REMS Post-marketing Study Required See Other Considerations for additional REMS information Pregnancy Rating C Executive Summary Efficacy Inhaled loxapine was superior to placebo in reducing acute agitation at 2 hours post dose measured by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale-Excited Component (PEC) in patients with bipolar I disorder and schizophrenia. -

Decrease in Brain Serotonin 2 Receptor Binding In

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Decrease in Brain Serotonin 2 Receptor Binding in Patients With Major Depression Following Desipramine Treatment A Positron Emission Tomography Study With Fluorine-18–Labeled Setoperone Lakshmi N. Yatham, MBBS, FRCPC; Peter F. Liddle, PhD, MBBS; Joelle Dennie, MSc; I-Shin Shiah, MD; Michael J. Adam, PhD; Carol J. Lane, MSc; Raymond W. Lam, MD; Thomas J. Ruth, PhD Background: The neuroreceptor changes involved in Results: Eight of the 10 patients responded to desipra- therapeutic efficacy of various antidepressants remain un- mine treatment as indicated by more than 50% decrease clear. Preclinical studies have shown that long-term ad- in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores. Depressed ministration of various antidepressants causes down- patients showed a significant decrease in 5-HT2 recep- regulation of brain serotonin 2 (5-HT2) receptors in rodents, tor binding as measured by setoperone binding in fron- but it is unknown if similar changes occur following anti- tal, temporal, parietal, and occipital cortical regions fol- depressant treatment in depressed patients. Our purpose, lowing desipramine treatment. The decrease in 5-HT2 therefore, was to assess the effects of treatment with desi- receptor binding was observed bilaterally and was par- pramine hydrochloride on brain 5-HT2 receptors in de- ticularly prominent in frontal cortex. pressed patients using positron emission tomography (PET) and fluorine-18 (18F)–labeled setoperone. Conclusions: Depressed patients showed a significant reduction in available 5-HT2 receptors in the brain fol- Methods: Eleven patients who met DSM-IV criteria for lowing desipramine treatment, but it is unknown if this major depression as determined by a structured clinical change in 5-HT2 receptors is due to clinical improve- interview for DSM-III-R diagnosis and suitable for treat- ment or an effect of desipramine that is unrelated to clini- ment with desipramine were recruited. -

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM DEPRESSANTS Opioid Pain Relievers Anxiolytics (Also Belong to Psychiatric Medication Category) • Codeine (In 222® Tablets, Tylenol® No

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM DEPRESSANTS Opioid Pain Relievers Anxiolytics (also belong to psychiatric medication category) • codeine (in 222® Tablets, Tylenol® No. 1/2/3/4, Fiorinal® C, Benzodiazepines Codeine Contin, etc.) • heroin • alprazolam (Xanax®) • hydrocodone (Hycodan®, etc.) • chlordiazepoxide (Librium®) • hydromorphone (Dilaudid®) • clonazepam (Rivotril®) • methadone • diazepam (Valium®) • morphine (MS Contin®, M-Eslon®, Kadian®, Statex®, etc.) • flurazepam (Dalmane®) • oxycodone (in Oxycocet®, Percocet®, Percodan®, OxyContin®, etc.) • lorazepam (Ativan®) • pentazocine (Talwin®) • nitrazepam (Mogadon®) • oxazepam ( Serax®) Alcohol • temazepam (Restoril®) Inhalants Barbiturates • gases (e.g. nitrous oxide, “laughing gas”, chloroform, halothane, • butalbital (in Fiorinal®) ether) • secobarbital (Seconal®) • volatile solvents (benzene, toluene, xylene, acetone, naptha and hexane) Buspirone (Buspar®) • nitrites (amyl nitrite, butyl nitrite and cyclohexyl nitrite – also known as “poppers”) Non-Benzodiazepine Hypnotics (also belong to psychiatric medication category) • chloral hydrate • zopiclone (Imovane®) Other • GHB (gamma-hydroxybutyrate) • Rohypnol (flunitrazepam) CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM STIMULANTS Amphetamines Caffeine • dextroamphetamine (Dexadrine®) Methelynedioxyamphetamine (MDA) • methamphetamine (“Crystal meth”) (also has hallucinogenic actions) • methylphenidate (Biphentin®, Concerta®, Ritalin®) • mixed amphetamine salts (Adderall XR®) 3,4-Methelynedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, Ecstasy) (also has hallucinogenic actions) Cocaine/Crack -

Schizophrenia Or Bipolar Disorder

Appendix D- NICE’s response to consultee and commentator comments on the draft scope and provisional matrix National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Proposed Single Technology Appraisal (STA) Loxapine inhalation for the treatment of acute agitation and disturbed behaviours associated with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder Response to consultee and commentator comments on the draft remit and draft scope (pre-referral) Comment 1: the draft remit Section Consultees Comments Action Appropriateness Alexza Yes as this topic is relevant to New Horizons: A Shared Vision for Mental Health Comment noted. No Pharmaceuticals (2009)1 and to The National Service Framework for Mental Health: Modern action required. Standards and Service Models (1999).2 Royal College of The appraisal of use of alternative matrices for drug delivery is important. It is Comment noted. No Pathologists particularly important in situation where there may be difficulties in administering action required. traditional drugs via intramuscular or intravenous routes. Therefore this worthy of NICE appraisal. Royal College of It is appropriate to consider novel methods to administer medications for this Comment noted. No Nursing condition. action required. Wording Alexza Revise to: Comment noted. Pharmaceuticals To appraise the clinical and cost effectiveness of Staccato® loxapine within the Consultees agreed that licensed indication for the rapid control of agitation and disturbed behaviors in the draft remit should patients with schizophrenia or in patients with bipolar -

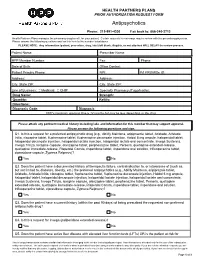

Antipsychotics

HEALTH PARTNERS PLANS PRIOR AUTHORIZATION REQUEST FORM Antipsychotics Phone: 215-991-4300 Fax back to: 866-240-3712 Health Partners Plans manages the pharmacy drug benefit for your patient. Certain requests for coverage require review with the prescribing physician. Please answer the following questions and fax this form to the number listed above. PLEASE NOTE: Any information (patient, prescriber, drug, labs) left blank, illegible, or not attached WILL DELAY the review process. Patient Name: Prescriber Name: HPP Member Number: Fax: Phone: Date of Birth: Office Contact: Patient Primary Phone: NPI: PA PROMISe ID: Address: Address: City, State ZIP: City, State ZIP: Line of Business: Medicaid CHIP Specialty Pharmacy (if applicable): Drug Name: Strength: Quantity: Refills: Directions: Diagnosis Code: Diagnosis: HPP’s maximum approval time is 12 months but may be less depending on the drug. Please attach any pertinent medical history including labs and information for this member that may support approval. Please answer the following questions and sign. Q1. Is this a request for a preferred antipsychotic drug (e.g., Abilify Maintena, aripiprazole tablet, Aristada, Aristada Initio, clozapine tablet, fluphenazine tablet, fluphenazine decanoate injection, Haldol 5 mg ampule, haloperidol tablet, haloperidol decanoate injection, haloperidol lactate injection, haloperidol lactate oral concentrate, Invega Sustenna, Invega Trinza, loxapine capsule, olanzapine tablet, perphenazine tablet, Perseris, quetiapine extended-release, quetiapine immediate-release, -

Quick Reference to Psychotropic Medications®

QUICK REFERENCE TO PSYCHOTROPIC MEDICATIONS ® DEVELOPED BY JOHN PRESTON, PSY.D., ABPP To the best of our knowledge recommended doses and side effects listed below are accurate. However, this is meant as a general reference only, and should not serve as a guideline for prescribing of medications. Please check the manufacturer’s product information sheet or the P.D.R. for any changes in dosage schedule or contraindications. (Brand names are registered trademarks.) ANTIDEPRESSANTS Usual Selective Action On NAMES Daily Dosage Neurotransmitters2 Generic Brand Range Sedation ACH 1 NE 5-HT DA imipramine Tofranil 150-300 mg mid mid + + +++ 0 desipramine Norpramin 150-300 mg low low +++++ 0 0 amitriptyline Elavil 150-300 mg high high ++ ++++ 0 nortriptyline Aventyl, Pamelor 75-125 mg mid mid +++ ++ 0 clomipramine Anafranil 150-250 mg high high 0 +++++ 0 trazodone Desyrel, Oleptro 150-400 mg mid none 0 ++++ 0 nefazodone Generic Only 100-300 mg mid none 0 +++ 0 ÁXR[HWLQH 3UR]DF 4, Sarafem 20-80 mg low none 0 +++++ 0 bupropion Wellbutrin 4 150-400 mg low none ++ 0 ++ sertraline Zoloft 50-200 mg low none 0 +++++ + SDUR[HWLQH 3D[LO PJ ORZ ORZ YHQODID[LQH (IIH[RU 4 75-350 mg low none +++ +++ + GHVYHQODID[LQH 3ULVWLT PJ ORZ QRQH ÁXYR[DPLQH /XYR[ PJ ORZ ORZ mirtazapine Remeron 15-45 mg mid mid +++ +++ 0 FLWDORSUDP &HOH[D PJ ORZ QRQH HVFLWDORSUDP /H[DSUR PJ ORZ QRQH GXOR[HWLQH &\PEDOWD PJ ORZ QRQH vilazodone Viibryd 10-40 mg low low 0 +++++ 0 DWRPR[HWLQH 6WUDWWHUD PJ ORZ ORZ YRUWLR[HWLQH %ULQWHOOL[ PJ ORZ QRQH levomilnacipran Fetzima -

Adasuve, INN-Loxapine

13 December 2012 EMA/91055/2013 Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) Assessment report Adasuve International non-proprietary name: loxapine Procedure No. EMEA/H/C/002400 Note Assessment report as adopted by the CHMP with all information of a commercially confidential nature deleted. 7 Westferry Circus ● Canary Wharf ● London E14 4HB ● United Kingdom Telephone +44 (0)20 7418 8400 Facsimile +44 (0)20 7523 7455 E -mail [email protected] Website www.ema.europa.eu An agency of the European Union © European Medicines Agency, 2013. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Contents 1. Background information on the procedure .............................................. 8 1.1. Submission of the dossier .................................................................................... 8 Information on Paediatric requirements ....................................................................... 8 Information relating to orphan market exclusivity .......................................................... 8 Scientific Advice ....................................................................................................... 8 Licensing status ....................................................................................................... 8 1.2. Steps taken for the assessment of the product ....................................................... 9 2. Scientific discussion .............................................................................. 10 2.1. Introduction ................................................................................................... -

Low-Dose Loxapine in the Treatment of Schizophrenia: Is It More Effective and More “Atypical” Than Standard-Dose Loxapine?

Low-Dose Loxapine in Schizophrenia Low-Dose Loxapine in the Treatment of Schizophrenia: Is It More Effective and More “Atypical” Than Standard-Dose Loxapine? Herbert Y. Meltzer, M.D., and Karuna Jayathilake, M.A. © Copyright 2000 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc. Loxapine is chemically related to clozapine and shares with it and other atypical antipsychotic drugs relatively greater affinity for serotonin (5-HT)2A than for dopamine D2 receptors. However, as is the case for risperidone, the occupancy of 5-HT2A and D2 receptors can range from partial to full, depending upon the dose. It was, therefore, of interest to determine whether loxapine at low doses (< 50 mg/day) might be at least as or more effective and more tolerable than usual clinical doses (≥ 60 mg/day). We retrospectively examined data from 75 patients treated with loxapine and found psychopathology data from 10 and 12 patients treated with low-dose or standard-dose loxapine, re- spectively. No data were available on the other 53 patients, 28 of whom were initially treated with low-dose and 25 with standard-dose loxapine. For those treated for at least 6 weeks, there was evi- dence of equivalent efficacy for both low- and standard-dose loxapine with regard to improvement in Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) and Global Assessment Scale scores. There were 6 patients with a history of neurolepticOne resistancepersonal among copy the may 22 completers. be printed Four of the low-dose group (40%) and 8 of the standard-dose group (67%) had at least a 20% decrease in BPRS total scores. Further study of the dose-response curve for loxapine and its usefulness in treating neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenia is indicated. -

Antipsychotic Medications Age and Step Therapy

Market Applicability Market DC GA KY MD NJ NY WA Applicable X X X NA X X X Antipsychotic Medications Age and Step Therapy Override(s) Approval Duration Prior Authorization 1 year Quantity Limit Atypical Antipsychotics Comment Quantity Limit Abilify Mycite (aripiprazole Non-Preferred May be subject to quantity with sensor) limit MSB Abilify Use MSB criteria Aripiprazole tablets Preferred Aripiprazole oral Non-Preferred disintegrating tablets Aripiprazole solution Non-Preferred clozapine tablets Preferred MSB Clozaril Use MSB criteria Caplyta (lumateperone) Non-Preferred capsules Fanapt (iloperidone) tablets Fanapt (iloperidone) Non-Preferred Titration Pack FazaClo (clozapine) oral Non-Preferred disintegrating tablets MSB Geodon capsules Use MSB Criteria Ziprasidone capsules Preferred MSB Invega tablets Use MSB criteria Paliperidone ER tablets Preferred Latuda (lurasidone) tablets Non-Preferred MSB Risperdal tablets, oral Use MSB criteria solution MSB Risperdal M-tabs oral Use MSB criteria disintegrating tablets Risperidone oral tablets Preferred Risperidone solution Preferred Risperdal oral disintegrating Non-Preferred tablets Saphris (asenapine) Non-Preferred sublingual tablets Secuado (asenapine) patch Non-Preferred CRX-ALL-0562-20 PAGE 1 of 8 06/09/2020 This policy does not apply to health plans or member categories that do not have pharmacy benefits, nor does it apply to Medicare. Note that market specific restrictions or transition-of-care benefit limitations may apply. Market Applicability Market DC GA KY MD NJ NY WA Applicable X -

Association of Sleep Among 30 Antidepressants: a Population-Wide Adverse Drug Reaction Study, 2004–2019

Association of sleep among 30 antidepressants: a population-wide adverse drug reaction study, 2004–2019 Andy R. Eugene Independent Researcher, Kansas, United States of America Independent Neurophysiology Unit, Department of Psychiatry, Medical University of Lublin, Lublin, Poland ABSTRACT Background. Sleep is one of the most essential processes required to maintain a healthy human life, and patients experiencing psychiatric illness often experience an inability to sleep. The aim of this study is to test the hypothesis that antidepressant compounds with strong binding affinities for the serotonin 5-HT2C receptor, histamine H1 receptors, or norepinephrine transporter (NET) will be associated with the highest odds of somnolence. Methods. Post-marketing cases of patient adverse drug reactions were obtained from the United States Food and Drug Administration Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS) during the reporting window of January 2004 to September 2019. Disproportionality analyses of antidepressants reporting somnolence were calculated using the case/non-case method. The reporting odds-ratios (ROR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were computed and all computations and graphing conducted in R. Results. There were a total of 69,196 reported cases of somnolence out of a total of 7,366,864 cases reported from January 2004 to September 2019. Among the 30 antidepressants assessed, amoxapine (n D 16) reporting odds-ratio (ROR) D 7.1 (95% confidence interval [CI] [4.3–11.7]), atomoxetine (n D 1,079) ROR D 6.6 (95% CI [6.2–7.1]), a compound generally approved for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and maprotiline (n D 18) ROR D 6.3 (95% CI, 3.9–10.1) were the top Submitted 21 November 2019 three compounds ranked with the highest reporting odds of somnolence. -

LOXITANE® (Loxapine Succinate USP Capsules LOXITANE® C (Loxapine Hydrochloride) Oral Concentrate LOXITANE® IM (Loxapine Hydrochloride) for Intramuscular Use Only

LOXITANE® (Loxapine Succinate USP Capsules LOXITANE® C (Loxapine Hydrochloride) Oral Concentrate LOXITANE® IM (Loxapine Hydrochloride) for Intramuscular Use Only Rx only WARNING Increased Mortality in Elderly Patients with Dementia-Related Psychosis Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death. Analyses of seventeen placebo-controlled trials (modal duration of 10 weeks), largely in patients taking atypical antipsychotic drugs, revealed a risk of death in drug-treated patients of between 1.6 to 1.7 times the risk of death in placebo-treated patients. Over the course of a typical 10-week controlled trial, the rate of death in drug-treated patients was about 4.5%, compared to a rate of about 2.6% in the placebo group. Although the causes of death were varied, most of the deaths appeared to be either cardiovascular (e.g., heart failure, sudden death) or infectious (e.g., pneumonia) in nature. Observational studies suggest that, similar to atypical antipsychotic drugs, treatment with conventional antipsychotic drugs may increase mortality. The extent to which the findings of increased mortality in observational studies may be attributed to the antipsychotic drug as opposed to some characteristic(s) of the patients is not clear. LOXITANE is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis (see WARNINGS). DESCRIPTION LOXITANE, loxapine, a dibenzoxazepine compound, represents a subclass of tricyclic antipsychotic agents, chemically distinct from the thioxanthenes, butyrophenones, and phenothiazines. Chemically, it is 2-Chloro-11 (4-methyl-1-piperazinyl)dibenz[b,f][1,4] oxazepine. It is present in capsules as the succinate salt, and in the concentrate and parenteral primarily as the hydrochloride salt.