A Return to Individual Virtue in Order to Overcome the Corruption of Climate Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GREEN AMERICAN GREENAMERICA.ORG 6 Simple Words to Move Us Forward, Faster 1612 K St

LIVE BETTER. SAVE MORE. INVEST WISELY. MAKE A DIFFERENCE. GREEN GREENAMERICA.ORG SPRING 2020AMERICAN ISSUE 117 Consume Less, Live More Making the most of what you have isn’t just good for the environment. Bucking wasteful consumer culture can build community and save money as individuals team up to save the planet. WHAT IS THE WHY WE SHOULD COME AS YOU GO GREEN CIRCULAR QUIT AMAZON p. 17 ARE: ZERO WASTE FOR FREE p. 24 ECONOMY? p. 14 FOR ALL p. 20 VisionCapital ColorLogo Ad 3/29/06 9:29 PM Page 1 Leave a Legacy of a Sustainable and Socially Just Future Green America has recently partnered with FreeWill to give all ofFREE our supporters a free and easy way to make aIS legally YOUR YOUR valid will in 25 minutes or less. MONEY VALUES Making a will is one of the best ways to support the people you love and the causes you care about the most. Many people like to include a gift to Green America to be an BIG GAP IN BETWEEN? importantGOOD part of the transformation to a socially just and YOU CAN BRIDGE THE GAP environmentally sustainable nation. with ▲▲▲▲▲▲ Individualized Portfolios Customized Social Criteria High Positive Social Impact Competitive Financial Returns Personalized Service Fossil Free Portfolios. Low Fixed Fees David Kim, President, a founder of Learn more at socialk.com Working Assets, in SRI since 1983. Start your legacy today at 1.800.366.8700 FreeWill.com/GreenAmerica www.visioncapitalinvestment.com It’s always free, and you can update it at any time. VISION CAPITAL FreeWill is not a law firm and its services are not a substitute for an attorney’s advice.INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT Socially Responsible Investing Were you born in 1949 or earlier? If you answered yes to that question, and you have a traditional IRA, then there’s a smarter way to give to Green America! You can make a contribution, also known as a Qualified Charitable Distribution (QCD), from your IRA that is 100% tax free, whether or not you itemize deductions on your tax return. -

Sustainability Leaders

new society publishers 2020 YEARS Sustainability Leaders Publishing Books for a World of Change 40 Years new society publishers is proud to be celebrating 40 years of activist, solutions-oriented publishing. From our roots in non-violent of Publishing civil disobedience training during the Vietnam war to today, with over for a World 500 books published — some across a dozen languages — we continue to bring positive solutions and cutting-edge ideas, to some of the most of Change troubling challenges of our time. Having never wavered from our mission to help build a just and ecologically sustainable society — placing planet and people before profit —we are proud to hold the highest environmental and social standards of any publisher in North America. With a dedicated community of changemakers and thought leaders, always working ahead of the curve, we look forward to another 40 years of bringing our readers books for a world of change. As the climate crisis accelerates and the coronavirus outbreak exposes the fragility of the just-in-time globalized, growth economy, we are focussed ever more on local resilience. Our Fall 2020 list is packed with practical books to get you started on building local capacity with how-to books on ecological land design, regenerative agriculture, and growing quality, nutritious local food – the very backbone of a resilient local economy. Yet resiliency is not all about food. We also offer tools for the deep inner work of personal transformation and methods for leveraging behavior change to build an inclusive society in which all voices are heard and all people can contribute. -

America Recycled Discussion Guide

www.influencefilmclub.com America Recycled Discussion Guide Directors: Noah Hussin, Tim Hussin Year: 2015 Time: 97 min You might know this director from: This is the first feature-length film from this directorial team. FILM SUMMARY Brothers Noah and Tim Hussin were provided with a life of comfort. Raised in a suburban setting in Florida where their needs were met and the stores supplied everything their hungry bellies desired, they arrived at the doorstep of adulthood feeling that there was something greater out there than store-bought conveniences and picket fences. Having gone their separate ways living abroad, they reconvened on home ground and agreed to hit the open road to figure out just what was left of the American Dream they had been raised to believe in. Tim directed the camera at the passing sights as the brothers’ bicycle tires tread southern roads, with Noah reflecting, “We aren’t the first to do this. We’re just chasing the great dream through our own eyes, riding the shoulders of those who paved the asphalt before us.” Bicycling 5,000 miles across the Southern states over a period of two years may not be the most common event, but road-tripping across America sure is. And while their actions may not be entirely new, those they meet—the homesteaders, the squatters, the anarchists and artists, the dumpster divers and roadkill eaters—offer a picture of an alternative America that is not often highlighted by the mainstream. While AMERICA RECYCLED travels across a variety of concepts—including food production, consumption, land development, community and family—it is through the people the brothers encounter that the overriding theme of self-discovery presents itself. -

Pring Your Source for Sustainability Volume VII No

Winter 2021 Wells pring Your source for sustainability Volume VII No. 2 Newsletter of the Center for Sustainability and the Environment at Wells College. Spring Sustainability Events All of our Spring semester 2021 sustainability-related presentations will be delivered online on the Zoom platform and recorded for later viewing. You may access the event links on our Upcoming Sustainability Events page on our website and/or later access the event recordings on our Sustainability Events Archive. In November, President Jon With the generous support of the National Fenestration Rating Council, we offered the latest event in our Sustainability Speaker series, which brings in nationally recognized presenters: Gibralter re-committed Wells College to this multi- February 16 “Be the Change” (recording available) sector collaboration of gov- Rob Greenfield, adventurer, environmental activist, humanitarian, and difference-maker ernors, tribal leaders, You’re just one in 7 billion people in a very confusing time on Earth. Is it possible for you to mayors, state legislators, make a difference? Is it worth trying? Rob Greenfield’s answer to these questions was a re- local officials, higher ed in- sounding “yes!” - he shared why and how you can be the change you wish to see in the world. stitutions, businesses, inves- Our Sustainability Perspectives series talks are offered on Mondays at 12:30PM. tors, faith groups, cultural institutions, and health care March 1 Climate Change Vulnerabilities in the Finger Lakes: What We Can Do About It organizations to reaffirm Dr. David Wolfe, professor, school of Integrative Plant Science, Cornell University our commitment to the Dr. Wolfe discussed local changes in the timing, frequency, intensity, and variability of crossing Paris Agreement on climate temperature and hydrological thresholds with negative (or positive) impacts on Finger Lakes change and pledge to part- terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. -

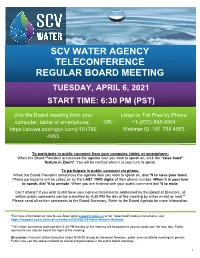

SCV Water Board Packet

SCV WATER AGENCY TELECONFERENCE REGULAR BOARD MEETING TUESDAY, APRIL 6, 2021 START TIME: 6:30 PM (PST) Join the Board meeting from your Listen in Toll Free by Phone computer, tablet or smartphone: -OR- +1-(833)-568-8864 https://scvwa.zoomgov.com/j/161786 Webinar ID: 161 786 4953 4953 To participate in public comment from your computer, tablet, or smartphone: When the Board President announces the agenda item you wish to speak on, click the “raise hand” feature in Zoom*. You will be notified when it is your turn to speak. To participate in public comment via phone: When the Board President announces the agenda item you wish to speak on, dial *9 to raise your hand. Phone participants will be called on by the LAST TWO digits of their phone number. When it is your turn to speak, dial *6 to unmute. When you are finished with your public comment dial *6 to mute. Can’t attend? If you wish to still have your comments/concerns addressed by the Board of Directors, all written public comments can be submitted by 4:30 PM the day of the meeting by either e-mail or mail.** Please send all written comments to the Board Secretary. Refer to the Board Agenda for more information. *For more information on how to use Zoom go to support.zoom.us or for “raise hand” feature instructions, visit https://support.zoom.us/hc/en-us/articles/205566129-Raise-Hand-In-Webinar **All written comments received after 4:30 PM the day of the meeting will be posted to yourscvwater.com the next day. -

Annual Report “We Are Focused on Building a Global Movement That Drives Positive Change for Our Planet by Accelerating Smart Environmental Giving.”

2017 Annual Report “We are focused on building a global movement that drives positive change for our planet by accelerating smart environmental giving.” —Kate Williams, CEO and Brant Barton, Board Chair 2 Dear Friends, 2017 was a big, extreme year at so many levels - political, social, cultural, economic, and, not least, environmental. One accurate telling of this past year celebrates its lasting opportunities in the form of private sector engagement and activism, with courageous citizens choosing to translate their care and sense of responsibility for each other and our planet into meaningful action. Another telling, of course, would feature its many challenging and frustrating aspects. We choose the former telling - this is the narrative that is true for 1% for the Planet: Our global network grew in size and activity across 2017, with both businesses and individuals joining the movement and creating robust partnerships with environmental nonprofits. Our diverse network demonstrated that when government steps back, when crises hit, we can always choose to take responsibility for creating positive change. We are focused on building a global movement that drives positive change for our planet by accelerating smart environmental giving. We are thrilled to share the following report in which we feature key metrics of success as well as partnership stories that illustrate our achievements and impact in 2017. As a diverse and truly global network, it’s impossible for us to capture the myriad amazing highlights across a 12-month period. Please consider this annual report a snapshot that we hope will help you to see the bigger picture. -

Journal 4576

Journal #4576 from sdc 12.24.19 Research Resources GrantStation Nevada says government’s covert ‘plutonium smuggling operation’ illegal Governor Orders Police at Mauna Kea to Stand Down Climate Crisis Threatens a Third of Plant Species, Endangering Food Supply Industry Money Backs Attorneys General Pushing for Atlantic Coast Pipeline Indigenous Women Unite to Defend the Amazon, Mother Earth and Climate Justice HUD News Dr. Cornel West On His Experiences at Standing Rock Little Shell Tribe celebrates federal recognition A Defense of Cursive, From a 10-Year-Old National Champion A Cree Artist Redraws History Inside the Plot to Murder Honduran Activist Berta Cáceres People Power in Romania Stopped a Mining Project. Now the Corporation Is Suing. The Future Of Eating Is The Past These Miniature Tools Taught Ancient Children How to Hunt and Fight VanDyke confirmed to 9th Circuit despite claims he’s ‘not a Nevadan‘ Water Shorts 'Smoke Signals' inducted into National Film Registry for its 'cultural significance' Twenty years.That's how much time has passed since the groundbreaking 'Smoke Signals' ..abqjournal.com Reservation high school students' film on missing and murdered Indigenous people wins award The film, created by Fort Washakie High School students, is an attempt to help raise awareness about the problem in Indian County and on the Wind River Reservation. trib.com Research Resources Indians of Arkansas: First Encounters - Arkansas Archeological Survey http://archeology.uark.edu / indiansofarkansas / index.html?pageName=Firs... - 71k - similar pagesJan 19, 2017 ... Soto's first contact with Arkansas Indians took place in May, 1541 (on the .... “ provinces” whose names fail to appear in later historical records? Native American Relations in Texas | TSLAC https://www.tsl.texas.gov/exhibits/indian/intro/page2.html - 46k - similar pagesJun 22, 2017 .. -

Growing Green International Contents Index

GROWING GREEN INTERNATIONAL CONTENTS INDEX Articles are from the UK unless indicated in red (and some titles have been changed a little for clarity) To search for any topic/name use Control+F Articles shown in blue are available online - click on the links All magazines are available in pdf form if you are a VON member, contact [email protected] 46 SPRING/SUMMER 2021 editor Tony Martin 06 Grow your own nuts (part 2) Addy Fern 10 Record harvests at La Ferme de L’Aube Jimmy Videle Canada 12 A revolution in lifestyle and agriculture Colleen McDuling 16 VON summer road tour 2020 Cherry Chung 19 Kindling Trust’s plans for a farm outside Manchester 25 Farmers for Stockfree Farming Rebecca Knowles 28 Grow Veganic Save the Planet Dan Graham 30 Rethinking Food and Agriculture (book by Amir & Laila Kassam) review by Kollibri terre Sonnenblume 34 The Garden of Vegan (book by Cleve West) review by Verona Barnes 36 A season on our farm Iain Tolhurst 39 From seed to plate (spinach and pea gnocchi) Piers Warren 41 Seed planting and human liberation Colin Denny Donoghue USA 43 Sad loss of VON activists Peter & Diana White David Graham 45 AUTUMN/WINTER 2020 editor Tony Martin 06 Growing Green: affordably, healthfully and ethically Colleen McDuling 10 Sowing on a shoestring (or budget gardening) Heather Fowler 11 Cooking in an emergency - some insights from 1939 Alina Congreve 14 Growing vertically Rosie Apps 17 A vegan permaculture garden in your kitchen Graham Burnett 25 Getting creative (or using the bits that we normally leave for the worms) -

Waste Wikipedia Waste Or Wastes Are Unwanted Or Unusable Materials

Waste wikipedia Waste or wastes are unwanted or unusable materials. Waste is any substance which is discarded after primary use, or is worthless, defective and of no use. It may be no longer useful as it has served its purpose, and at the end of the process have no further use, and it is generally discarded. It is unwanted materials and objects that people have thrown away. It is often also called trash , garbage , rubbish , or junk. It can be solid , liquid , or gas , or it can be waste heat. There are many different kinds of waste. Garbage is the waste we produce daily in our homes, including old or unwanted food, chemical substances, paper, broken furniture, used containers, and other things. When waste is a liquid or gas, it can be called an emission. This is usually pollution. Sanitation is proper handling of human waste. Waste can also be something abstract something that you cannot touch , for example "a waste of time" or "wasted opportunities". When people use the words waste or wasted in this way, they are saying directly or indirectly that something has been used badly using too much of it or using it incorrectly. People have thrown away waste in heaps for thousands of years. In modern homes and businesses , garbage is normally placed in waste containers of some sort. It is then moved to the street, where it can be collected and taken to a place designed to hold, destroy or recycle garbage. Some waste materials, such as paper , wood , glass , metals , and plastic containers , can be recycled reused. -

Issue No. 18 Spring 2020 £1 ‘A Prevailing Wind’ by Merlyn Chesterman the HARTLAND POST a Quarterly News Magazine for Hartland and Surrounding Area Issue No

THE HARTLAND POST First published in 2015, in the footsteps of Thomas Cory Burrow’s “Hartland Chronicle” (1896-1940) and Tony Manley’s “Hartland Times” (1981-2014) Issue No. 18 Spring 2020 £1 ‘A Prevailing Wind’ by Merlyn Chesterman THE HARTLAND POST A quarterly news magazine for Hartland and surrounding area Issue No. 18 Spring 2020 Printed by Jamaica Press, Published by The Hartland Post All communications to: The Editor, Sally Crofton, Layout: Kris Tooke 102 West Street, EX39 6BQ Hartland. Cover Artwork: Laura Zalewski Tel. 01237 441617 Email: [email protected] Website: John Zalewski ANNOUNCEMENTS Reuben Henry Waters - born 28 January 2020 Ida Keens Weighing 8lb 3oz Ida Keens of Baxworthy Cross celebrated her 102nd Birthday on Son of Chloe and Josh Waters of Launcells. Boxing day. A party was held at the British Legion that evening. Reuben is the first grandchild of Shaun and Bev Pengilly of She was accompanied by family and friends. A buffet and a Philham and great grandson to Janet Pengilly of Hartland, Jim birthday cake was kindly laid on, with fun and the usual laughter. Conibear of Hartland and Carol Hadcroft of Bideford. My thanks to the Legion and all involved in Ida's party, a Reuben is the sixth grandchild of David and Marion Waters and memorable evening. a new great grandson for Joyce Bate of Tresmeer, Launceston. Congratulations Mum, with love from your family. Previous issues of the Hartland Post are available online Advertising costs:Advertising 1 slot (1/18th costs page) £30/year, at thehartlandpost.com. This issue will be available 2 slotsSmall £55/year, ads 1/18th ¼ page of a£110/year, page: £25/year ½ page (4 £150/year,issues) online when the next issue is on the news stands. -

Cuadernillo De Ingreso 2018

I.S.F.D. y T N°103 - Profesorados de Historia y Geografía C UADERNILLO DE INGRESO 2 0 1 8 | 1 Actividades: I.S.F.D. y T N°103 - Profesorados de Historia y Geografía CUADERNO DE ESTUDIO Y DE ACTIVIDADES PARA 1º AÑO Ingreso 2018 ÍNDICE Carta al ingresante Pág. 4 Manifiesto de ideas, valores e intenciones Pág. 7 TEXTO Nº1 Pág. 11 TEXTO N2 Pág. 14 TEXTO Nº3 Pág. 18 TEXTO Nº4 Pág. 25 TEXTO Nº5 Pág. 29 TEXTO Nº6 Pág. 33 TEXTO Nº7 Pág. 34 TEXTO Nº8 Pág. 52 TEXTO Nº 9 Pag. 64 TEXTO Nº10 Pág. 74 TEXTO Nº11 Pág. 80 TEXTO Nº12 Pág. 89 TEXTO Nº13 Pág. 93 TEXTO Nº14 Pág. 99 TEXTO Nº15 Pág. 109 TEXTO Nº16 Pág. 117 TEXTO Nº17 Pág. 119 TEXTO Nº18 Pág. 121 TEXTO Nº19 Pág. 126 TEXTO Nº20 Pág. 130 TEXTO Nº21 Pág. 135 TEXTO Nº22 Pág. 144 TEXTO Nº23 Pág.150 TEXTO Nº24 Pág.154 TEXTO Nº25 Pág. 156 TEXTO Nº26 Pág. 160 TEXTO Nº27 Pág. 169 TEXTO Nº28 Pág. 183 TEXTO Nº29 Pág. 188 C UADERNILLO DE INGRESO 2 0 1 8 | 2 Actividades: I.S.F.D. y T N°103 - Profesorados de Historia y Geografía Los textos presentados en este cuadernillo son selecciones realizadas por los profesores de los primeros años para ser trabajados a lo largo del primer cuatrimestre de clases. El hecho de leerlos y realizar las actividades propuestas significa una clara ventaja para el estudiante, es por ello que proponemos su lectura. Las actividades serán corregidas en clase. Luego cada docente determinara como realizara la evaluación en su espacio. -

Zero-Waste Bloggers: the Millennials Who Can Fit a Year’S Worth of Trash in a Jar by Leilani Clark, the Guardian, Apr

Zero-Waste Bloggers: The Millennials Who Can Fit a Year’s Worth of Trash in a Jar By Leilani Clark, The Guardian, Apr. 22, 2018 Kathryn Kellogg, a 25-year-old print shop employee, spends four hours a day on her lifestyle blog Going Zero Waste. She posts on Instagram, engag- es with Facebook followers, and writes about homemade eyeliner and lip balm, worm composting, and shopping bulk bins – anything to avoid unnec- essary waste. Her trash for the past year – anything that hasn’t been com- posted or recycled – fits in an 8oz jar. Kellogg is earnest, enthusiastic, and admittedly still figuring out what it means to be zero waste. The aspiring actor has also weathered her fair share of criticism. “I’m not even that big yet and I get so much hate mail,” says Kellogg, who draws 10,000 unique page views a month and has 800 subscribers. Photo: Andrew Burton Since the launch of Going Zero Waste in March 2015, she’s been criticized on social media and in pri- vate messages for driving and flying, for not installing a grey-water system, and, no joke, for using toilet paper (she does have a bidet, by the way). She’s been chastised by vegans for eating eggs, and one visiting relative walked around Kellogg’s house pointing out anything made of plastic. She’s also been called out as overly privileged, even though she lives in a modest two-bedroom house in Vallejo, a blue-collar city 32 miles north-east of San Francisco. “They just nitpick every little thing because zero waste sounds like such an ultimatum,” Kellogg says.