Studies in the Roman Province of Dalmatia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Illyrian Religion and Nation As Zero Institution

Studies in Visual Arts and Communication: an international journal Vol 3, No 1 (2016) on-line ISSN 2393 - 1221 Illyrian religion and nation as zero institution Josipa Lulić * Abstract The main theoretical and philosophical framework for this paper are Louis Althusser's writings on ideology, and ideological state apparatuses, as well as Rastko Močnik’s writings on ideology and on the nation as the zero institution. This theoretical framework is crucial for deconstructing some basic tenants in writing on the religious sculpture in Roman Dalmatia, and the implicit theoretical constructs that govern the possibilities of thought on this particular subject. This paper demonstrates how the ideological construct of nation that ensures the reproduction of relations of production of modern societies is often implicitly or explicitly projected into the past, as trans-historical construct, thus soliciting anachronistic interpretations of the material remains of past societies. This paper uses the interpretation of religious sculpture in Roman Dalmatia as a case study to stress the importance of the critique of ideology in the art history. The religious sculpture in Roman Dalmatia has been researched almost exclusively through the search for the presumed elements of Illyrian religion in visual representations; the formulation of the research hypothesis was firmly rooted into the idea of nation as zero institution, which served as the default framework for various interpretations. In this paper I try to offer some alternative interpretations, intending not to give definite answers, but to open new spaces for research. Keywords: Roman sculpture, province of Dalmatia, nation as zero institution, ideology, Rastko Močnik, Louis Althusser. -

The First Illyrian War: a Study in Roman Imperialism

The First Illyrian War: A Study in Roman Imperialism Catherine A. McPherson Department of History and Classical Studies McGill University, Montreal February, 2012 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts ©Catherine A. McPherson, 2012. Table of Contents Abstract ……………………………………………….……………............2 Abrégé……………………………………...………….……………………3 Acknowledgements………………………………….……………………...4 Introduction…………………………………………………………………5 Chapter One Sources and Approaches………………………………….………………...9 Chapter Two Illyria and the Illyrians ……………………………………………………25 Chapter Three North-Western Greece in the Later Third Century………………………..41 Chapter Four Rome and the Outbreak of War…………………………………..……….51 Chapter Five The Conclusion of the First Illyrian War……………….…………………77 Conclusion …………………………………………………...…….……102 Bibliography……………………………………………………………..104 2 Abstract This paper presents a detailed case study in early Roman imperialism in the Greek East: the First Illyrian War (229/8 B.C.), Rome’s first military engagement across the Adriatic. It places Roman decision-making and action within its proper context by emphasizing the role that Greek polities and Illyrian tribes played in both the outbreak and conclusion of the war. It argues that the primary motivation behind the Roman decision to declare war against the Ardiaei in 229 was to secure the very profitable trade routes linking Brundisium to the eastern shore of the Adriatic. It was in fact the failure of the major Greek powers to limit Ardiaean piracy that led directly to Roman intervention. In the earliest phase of trans-Adriatic engagement Rome was essentially uninterested in expansion or establishing a formal hegemony in the Greek East and maintained only very loose ties to the polities of the eastern Adriatic coast. -

The Herodotos Project (OSU-Ugent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography

Faculty of Literature and Philosophy Julie Boeten The Herodotos Project (OSU-UGent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography Barbarians in Strabo’s ‘Geography’ (Abii-Ionians) With a case-study: the Cappadocians Master thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Linguistics and Literature, Greek and Latin. 2015 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Mark Janse UGent Department of Greek Linguistics Co-Promotores: Prof. Brian Joseph Ohio State University Dr. Christopher Brown Ohio State University ACKNOWLEDGMENT In this acknowledgment I would like to thank everybody who has in some way been a part of this master thesis. First and foremost I want to thank my promotor Prof. Janse for giving me the opportunity to write my thesis in the context of the Herodotos Project, and for giving me suggestions and answering my questions. I am also grateful to Prof. Joseph and Dr. Brown, who have given Anke and me the chance to be a part of the Herodotos Project and who have consented into being our co- promotores. On a whole other level I wish to express my thanks to my parents, without whom I would not have been able to study at all. They have also supported me throughout the writing process and have read parts of the draft. Finally, I would also like to thank Kenneth, for being there for me and for correcting some passages of the thesis. Julie Boeten NEDERLANDSE SAMENVATTING Deze scriptie is geschreven in het kader van het Herodotos Project, een onderneming van de Ohio State University in samenwerking met UGent. De doelstelling van het project is het aanleggen van een databank met alle volkeren die gekend waren in de oudheid. -

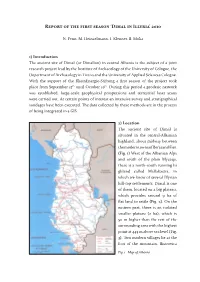

Report of the First Season 'Dimal in Illyria' 2010

Report of the first season ‘Dimal in Illyria’ 2010 N. Fenn, M. Heinzelmann, I. Klenner, B. Muka 1) Introduction The ancient site of Dimal (or Dimallon) in central Albania is the subject of a joint research project lead by the Institute of Archaeology of the University of Cologne, the Department of Archaeology in Tirana and the University of Applied Sciences Cologne. With the support of the RheinEnergie-Stiftung a first season of the project took place from September 15th until October 19th. During this period a geodetic network was established, large-scale geophysical prospections and terrestrial laser scans were carried out. At certain points of interest an intensive survey and stratigraphical sondages have been executed. The data collected by these methods are in the process of being integrated in a GIS. 2) Location The ancient site of Dimal is situated in the central-Albanian highland, about midway between the modern towns of Berat and Fier. (Fig. 1) West of the Albanian Alps and south of the plain Myzeqe, there is a north-south running hi ghland called Mallakastra, in which we know of several Illyrian hill-top settlements. Dimal is one of them, located on a big plateau, which provides around 9 ha of flat land to settle (Fig. 2). On the eastern part, there is an isolated smaller plateau (2 ha), which is 50 m higher than the rest of the surrounding area with the highest point at 445 m above sea level (Fig. 3). Two modern villages lie at the foot of the mountain, Bistrovica Fig. 1 - Map of Albania REPORT OF THE FIRST SEASON ‘DIMAL IN ILLYRIA’ 2010 Fig. -

University of Zadar [email protected] Tea TEREZA VIDOVIĆ-SCHRE

LINGUA MONTENEGRINA, god. XIII/1, br. 25, Cetinje, 2020. Fakultet za crnogorski jezik i književnost UDK 070:929Bettiza E. Izvorni naučni rad Josip MILETIĆ (Zadar) University of Zadar [email protected] Tea TEREZA VIDOVIĆ-SCHREIBER (Split) University of Split [email protected] DALMATIA – BETTIZA’S LOST HOMELAND The paper analyses the potential of Bettiza’s fiction for the deve- lopment of Croatian and Italian cultural relations as well as tourist promotion of the Croatian historical region of Dalmatia. Particular attention is focused on the novel Exile, in which the author writes a family chronicle by evoking his Split roots. At the same time, he describes the atmosphere, customs and picturesque figures of Dal- matian towns in the interwar period, the encounter of Slavic and Roman culture, as well as the destiny of the Italian population there who, due to the turmoil of war and socialist revolution, decided to leave their homeland. Reception of Bettiza’s work, as an account of an individual history that is completely different from the written (national), the collective history, can positively affect the Italian perception of Dalmatia as a tourist destination, and it can improve the distorted image of Croats living there, which has been created for decades in Italy, through the activist action of extreme groups, therefore it can be of multiple use. Proving that not all Italians for- cibly left their former homeland, but that a part of them left freely seeking a better life for themselves and their families not seeing any perspective in the upcoming communism, allows for the constructi- on of bridges between Slavic and Roman culture, and an even better and more effective tourism promotion of this Croatian region in the context of Italian tourist interests. -

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome William E. Dunstan ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Plymouth, UK ................. 17856$ $$FM 09-09-10 09:17:21 PS PAGE iii Published by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.rowmanlittlefield.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright ᭧ 2011 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. All maps by Bill Nelson. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. The cover image shows a marble bust of the nymph Clytie; for more information, see figure 22.17 on p. 370. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dunstan, William E. Ancient Rome / William E. Dunstan. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7425-6832-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-7425-6833-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-7425-6834-1 (electronic) 1. Rome—Civilization. 2. Rome—History—Empire, 30 B.C.–476 A.D. 3. Rome—Politics and government—30 B.C.–476 A.D. I. Title. DG77.D86 2010 937Ј.06—dc22 2010016225 ⅜ϱ ீThe paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/ NISO Z39.48–1992. Printed in the United States of America ................ -

Vladimir-Peter-Goss-The-Beginnings

Vladimir Peter Goss THE BEGINNINGS OF CROATIAN ART Published by Ibis grafika d.o.o. IV. Ravnice 25 Zagreb, Croatia Editor Krešimir Krnic This electronic edition is published in October 2020. This is PDF rendering of epub edition of the same book. ISBN 978-953-7997-97-7 VLADIMIR PETER GOSS THE BEGINNINGS OF CROATIAN ART Zagreb 2020 Contents Author’s Preface ........................................................................................V What is “Croatia”? Space, spirit, nature, culture ....................................1 Rome in Illyricum – the first historical “Pre-Croatian” landscape ...11 Creativity in Croatian Space ..................................................................35 Branimir’s Croatia ...................................................................................75 Zvonimir’s Croatia .................................................................................137 Interlude of the 12th c. and the Croatia of Herceg Koloman ............165 Et in Arcadia Ego ...................................................................................231 The catastrophe of Turkish conquest ..................................................263 Croatia Rediviva ....................................................................................269 Forest City ..............................................................................................277 Literature ................................................................................................303 List of Illustrations ................................................................................324 -

The Top-Ranking Towns in the Balkan and Pannonian Provinces of the Roman Empire Najpomembnejša Antična Mesta Balkanskih Provinc in Obeh Panonij

Arheološki vestnik 71, 2020, 193–215; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3986/AV.71.05 193 The top-ranking towns in the Balkan and Pannonian provinces of the Roman Empire Najpomembnejša antična mesta balkanskih provinc in obeh Panonij Damjan DONEV Izvleček Rimska mesta balkanskih in podonavskih provinc so bila doslej le redko del raziskav širših mestnih mrež. Namen prispevka je prepoznati glavne značilnosti mestnih sistemov in na podlagi najpomembnejših mest provincialne mestne hierarhije poiskati njihovo vpetost v ekonomijo provinc v času severske dinastije. Avtor se osredotoča na primerjavo veli- kosti prvorazrednih mest z ostalimi naselbinami, upošteva pa tudi njihovo lego in kmetijsko bogastvo zaledja. Ugotavlja, da moramo obravnavano območje glede na ekonomske vire razumeti kot obrobje rimskega imperija. Glavna bogastva obravnavanih provinc so bili namreč les, volna, ruda in delovna sila, kar se jasno izraža tudi v osnovnih geografskih parametrih prvorazrednih mest: v njihovi relativno skromni velikosti, obrobni legi in vojaški naravi. Ključne besede: Balkanski polotok; Donava; principat; urbanizacija; urbani sistemi Abstract The Roman towns of the Balkan and Danube provinces have rarely been studied as parts of wider urban networks. This paper attempts to identify the principle features of these urban systems and their implications for the economy of the provinces at the time of the Severan dynasty, through the prism of the top-ranking towns in the provincial urban hierarchies. The focus will be on the size of the first-ranking settlements in relation to the size of the lower-ranking towns, their location and the agricultural riches of their hinterlands. One of the main conclusions of this study is that, from an economic perspective, the region under study was a peripheral part of the Roman Empire. -

Modell Des Rae TEE II

Modell des RAe TEE II 39540 Informationen zum Vorbild: Informations relatives au modèle réel : Der Triebzug RAe TEE II wurde als Viersystem Triebzug Le train automoteur RAe TEE II fut construit en 1961 pour 1961 für die SBB gebaut. Dies hatte den Vorteil, dass der les CFF comme train automoteur quadricourant. Cette Zug ohne große Aufenthaltszeiten an den Systemgrenzen conception présentait l’avantage de pouvoir utiliser ce eingesetzt wurde. Neben dem besonderen Komfort, be- train sans arrêt prolongé aux frontières des systèmes. saß der Zug nur Wagen der 1. Klasse. Die Antriebseinheit Outre son confort particulier, le train possédait unique- ist im Original, wie im Modell im Mittelwagen unterge- ment des voitures de 1re classe. L’unité motrice est logée bracht. Nur der Mittelwagen ist mit einem Seitengang, die dans la voiture centrale, dans le train réel comme sur restlichen Wagen sind als Großraumwagen eingerichtet. le modèle réduit. Seule la voiture centrale présente un Seine Einsätze waren unter anderem: couloir latéral, les autres sont à couloir central. Ce train - TEE „Gottardo“ Zürich – Milano – Zürich fut utilisé entre autres sur les lignes suivantes : - TEE „Cisalpin“ Milano – Paris – Milano - TEE „Gottardo“ Zurich – Milan – Zurich - TEE „Edelweiss“ Zürich – Amsterdam – Zürich - TEE „Cisalpin“ Milan – Paris – Milan Nach 30 Jahren Einsatz wurden die Züge umgebaut und - TEE „Edelweiss“ Zurich – Amsterdam – Zurich als Euro City eingestuft. Seit dieser Zeit gab es auch Après 30 années de service, ces trains furent transfor- Wagen der 2.Klasse im Zugverband. més et classés Euro City. Depuis, les rames comportent également des voitures de 2nde classe. Information about the Prototype: Informatie over het voorbeeld: The RAe TEE II powered rail car train was built for the SBB Het treinstel RAe TEE II werd in 1961 als vier-systemen in 1961 as a four-system powered rail car train. -

Compositions Grandes Lignes, Époque Ivb 1980-1990

Composition des trains grandes lignes – Bourgogne - 1500V - époque IVb 1980-1990 HIVER 1980/81 EXP 5320 BOURG ST MAURICE- LE HAVRE CC 7100 + B9c9x UIC + A4c4B5c5x UIC + B9c9x UIC + B9c9x UIC + A4c4B5c5x UIC + B9c9x UIC + B9c9x UIC + A4c4B5c5x UIC + B9c9x UIC + B9c9x UIC + A4c4B5c5x UIC + B9c9x UIC ETE 1980 RAP 182 “LE TRAIN BLEU” VINTIMILLE - PARIS BB 22200 + WLAB T2 + WLAB T2 + WLAB MU + WLAB MU + WLAB MU + B10c10x VU + B10c10x VU + B9c9x UIC + B10c10x VU + B10c10x VU + B10c10x VU + B10c10x VU + B10c10x VU + B10c10x VU RAP 196 “L’ESTEREL” NICE - PARIS BB 22200 + B10c10x VU + B10c10x VU + B10c10x VU + B10c10x VU + B10c10x VU + B10c10x VU + B10c10x VU + B10c10x VU + WLAB T2 + WLAB T2 + WLAB MU + Dd4 UIC Rmb – Rails miniatures de la boucle Sigle SNCF : 1985 "nouille", 1992 "casquette", 2005 "carmillon" 1 Composition des trains grandes lignes – Bourgogne - 1500V - époque IVb 1980-1990 RAP 5018 “COTE D’AZUR” NICE - PARIS BB 22200 + B10 UIC + B10 UIC + B10 UIC + A8j DEV + A4c4B5cx UIC + B9c9x UIC + B9c9x UIC + B9c9x UIC + B9c9x UIC + B9c9x UIC + A9c9x VU + A9c9x VU + A9c9x VU RAP 5024 NICE - PARIS BB 7200 + A9u VSE + B11tu VTU + B11tu VTU + B11tu VTU + B6Du VU + B11tu VTU + B11tu VTU + B11tu VTU + VR GE + A9u VSE + A9u VSE + A10tu VTU + A9u VSE + B11tu VTU EXP 5061 PARIS - VINTIMILLE BB 22200 + WLAB MU + WLAB T2 + A9c9x VU + B10c10x VU +A9 UIC + B10 UIC + B10 UIC + B10 UIC + B10 UIC + B10c10x VU + A9c9x VU + A9c9x VU + A9c9x VU + Dd2s MC76 + Paz UIC Rmb – Rails miniatures de la boucle Sigle SNCF : 1985 "nouille", 1992 "casquette", 2005 "carmillon" -

Albanian Political Activity in Ottoman Empire (1878-1912)

World Journal of Islamic History and Civilization, 3 (1): 01-08, 2013 ISSN 2225-0883 © IDOSI Publications, 2013 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.wjihc.2013.3.1.3101 Albanian Political Activity in Ottoman Empire (1878-1912) Agata Biernat Faculty of Political Sciences and International Studies, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Gagarina 11, Torun, Poland Abstract: This article sketches briefly the Albanian political activity in Ottoman Empire from their “National Renaissance” to 1912 when Albania became an independent country. In the second half of XIX century Albanians began their national revival. The great influence in that process had Frashëri brothers: Abdyl, Naim and Sami. They played a prominent role in Albanian national movement. Their priority was to persuade Ottomans as well as Great Powers that Albanians were a nation, which is why had a right to have an autonomy within Empire. The most important Albanian organization at that time was League of Prizrën – its leaders took part in Congress of Berlin (1878), unfortunately they heard only a lot of objections from European leaders. The culmination of Rilindja was a proclamation of Albania’s independence led by Ismail Qemali in Vlora, on 28 November 1912. Key words: Albania Albanian National Awakening The Ottoman Empire League of Prizrën Frashëri brothers INTRODUCTION national schools. Local Albanian Bey also opposed the reform because it sought to maintain their privileges. The nineteenth century was an introduction for the Slowly they started thinking about the history of their political and economic collapse of the great Ottoman nation, origins and also about final codification of Empire. This process was accompanied by the slow but Albanian language. -

Pages from the History of the Autariatae and Triballoi

www.balcanica.rs http://www.balcanica.rs UDC: 939.8:904-034:739.57.7.032 Original Scholarly Work RastkoVASIÓ Institute for Archaeology Belgrade PAGES FROM THE HISTORY OF THE AUTARIATAE ANDTRIBALLOI Abstract.- According to Strabo (VII, 5,11), the Autariatae were the best and largest Illyrian tribe which, at the apex of its power, vanquished the Triballoi and other Illyrian and Thracian tribes. The author discusses the information offered by classical sources and, as others before him, connects them with archaeologically documented groups in the central Balkans, the Glasinac and Zlot groups. Among the scarce information left by the classical authors regarding events in the central Balkans during the Iron Age we have singled out as par ticularly important the conflict between the Autariatae and the Triballoi, from which the former emerged victorious. True, several dramatic events shook the central Balkans at that time - it suffice to mention the Celtic invasion in the late 4th and early 3rd centuries B. C, when the Celts reached Greece - but those in volved peoples and groups that had come from elsewhere and cannot be con sidered Balkanic. The Autariatae and the Triballoi, on the contrary, can be clas sified as central Balkanic tribes with a fair amount of certainty, and therefore their conflict was truly one of the central events of palaeo-Balkanic history. According to Strabo (VII, 5, 11), the Autariatae were the finest and big gest Illyrian tribe. They fought and vanquished the Triballoi as well as other II- lyrians and Thracians. This passage from Strabo was extensively discussed by lin guists, historians, and archaeologists, who finally agreed to date the conflict dis cussed in it to before the middle of the 5th c.