William Dunbar: an Analysis of His Poetic Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr Sally Mapstone “Myllar's and Chepman's Prints” (Strand: Early Printing)

Programme MONDAY 30 JUNE 10.00-11.00 Plenary: Dr Sally Mapstone “Myllar's and Chepman's Prints” (Strand: Early Printing) 11.00-11.30 Coffee 11.30-1.00 Session 1 A) Narrating the Nation: Historiography and Identity in Stewart Scotland (c.1440- 1540): a) „Dream and Vision in the Scotichronicon‟, Kylie Murray, Lincoln College, Oxford. b) „Imagined Histories: Memory and Nation in Hary‟s Wallace‟, Kate Ash, University of Manchester. c) „The Politics of Translation in Bellenden‟s Chronicle of Scotland‟, Ryoko Harikae, St Hilda‟s College, Oxford. B) Script to Print: a) „George Buchanan‟s De jure regni apud Scotos: from Script to Print…‟, Carine Ferradou, University of Aix-en-Provence. b) „To expone strange histories and termis wild‟: the glossing of Douglas‟s Eneados in manuscript and print‟, Jane Griffiths, University of Bristol. c) „Poetry of Alexander Craig of Rosecraig‟, Michael Spiller, University of Aberdeen. 1.00-2.00 Lunch 2.00-3.30 Session 2 A) Gavin Douglas: a) „„Throw owt the ile yclepit Albyon‟ and beyond: tradition and rewriting Gavin Douglas‟, Valentina Bricchi, b) „„The wild fury of Turnus, now lyis slayn‟: Chivalry and Alienation in Gavin Douglas‟ Eneados‟, Anna Caughey, Christ Church College, Oxford. c) „Rereading the „cleaned‟ „Aeneid‟: Gavin Douglas‟ „dirty‟ „Eneados‟, Tom Rutledge, University of East Anglia. B) National Borders: a) „Shades of the East: “Orientalism” and/as Religious Regional “Nationalism” in The Buke of the Howlat and The Flyting of Dunbar and Kennedy‟, Iain Macleod Higgins, University of Victoria . b) „The „theivis of Liddisdaill‟ and the patriotic hero: contrasting perceptions of the „wickit‟ Borderers in late medieval poetry and ballads‟, Anna Groundwater, University of Edinburgh 1 c) „The Literary Contexts of „Scotish Field‟, Thorlac Turville-Petre, University of Nottingham. -

Amanda Holton University of Reading

Chaucer and Pronominatio Amanda Holton University of Reading Pronominatio, or antonomasia, is the replacement of a proper noun with another noun or adjective or a periphrastic formulation, such as 'Cristes mooder' for Mary.] I apply the term only when the reader needs some knowledge outside the immediate context in order to understand the reference and when the name itself is not given at all in surrounding lines. 2 Pronominatio is a fairly common figure in classical and medieval literature, and Chaucer encountered it in a number of his sources; indeed this article, while it focuses on Chaucer's practice, also indicates how it is used in a range of his sources and analogues. The figure is discussed in various classical and medieval rhetorical manuals, featuring, for example, in the Rhetorica Ad Herennium and in Quintilian' s /nstitutio oratoria3 Chaucer's own use of it as a freestanding figure is sparse, highly selective and often pointed, and reveals mixed feelings about its potential, for he is very conscious of how it can express both grandeur and pomposity, splendour and insincerity. After discussing Chaucer's preferred methods of denoting people and places, this article examines how his use of pronominatio relates to his response to Virgil, and, by extension, how he uses the figure as a marker of epic style in several texts. It then demonstrates how he exploits its more negative possibilities when denoting Diomede in Troilus and Criseyde and Mary in the Prioress's Tale. On the whole Chaucer shows a strong preference for simple and direct naming, and will often reject pronominatio even when he encounters it in a source he otherwise favours stylistically. -

The Culture of Literature and Language in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland

The Culture of Literature and Language in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland 15th International Conference on Medieval and Renaissance Scottish Literature and Language (ICMRSLL) University of Glasgow, Scotland, 25-28 July 2017 Draft list of speakers and abstracts Plenary Lectures: Prof. Alessandra Petrina (Università degli Studi di Padova), ‘From the Margins’ Prof. John J. McGavin (University of Southampton), ‘“Things Indifferent”? Performativity and Calderwood’s History of the Kirk’ Plenary Debate: ‘Literary Culture in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland: Perspectives and Patterns’ Speakers: Prof. Sally Mapstone (Principal and Vice-Chancellor of the University of St Andrews) and Prof. Roger Mason (University of St Andrews and President of the Scottish History Society) Plenary abstracts: Prof. Alessandra Petrina: ‘From the margins’ Sixteenth-century Scottish literature suffers from the superimposition of a European periodization that sorts ill with its historical circumstances, and from the centripetal force of the neighbouring Tudor culture. Thus, in the perception of literary historians, it is often reduced to a marginal phenomenon, that draws its force solely from its powers of receptivity and imitation. Yet, as Philip Sidney writes in his Apology for Poetry, imitation can be transformed into creative appropriation: ‘the diligent imitators of Tully and Demosthenes (most worthy to be imitated) did not so much keep Nizolian paper-books of their figures and phrases, as by attentive translation (as it were) devour them whole, and made them wholly theirs’. The often lamented marginal position of Scottish early modern literature was also the key to its insatiable exploration of continental models and its development of forms that had long exhausted their vitality in Italy or France. -

Which Vernacular Revival? Burns and the Makars R.D.S

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 30 | Issue 1 Article 4 1-1-1998 Which Vernacular Revival? Burns and the Makars R.D.S. Jack Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Jack, R.D.S. (1998) "Which Vernacular Revival? Burns and the Makars," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 30: Iss. 1. Available at: http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol30/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the USC Columbia at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. R. D. S. Jack Which Vernacular Revival? Burns and the Makars When I was introduced to Bums at university, he was properly described as the senior member of a poetic trinity. With Ramsay and Fergusson, we were told, he initiated something called "The Vernacular Revival." That is, in the eighteenth century these poets revived poetic use of Scots ("THE vernacular") after a seventeenth century of treacherous anglicization caused by James VI and the Union of the Crowns. Sadly, as over a hundred years had elapsed, this worthy rescue effort might resuscitate but could never restore the national lan guage to the versatility in fullness of Middle Scots. This pattern and these words-national language, treachery, etc.-still dominate Scottish literary history. They are based on modem assumptions about language use within the United Kingdom. To see Bums's revival of the Scots vernacular in primarily political terms conveniently makes him anticipate the linguistic position of that self-confessed twentieth-century Anglophobe, C. -

Full Bibliography (PDF)

SOMHAIRLE MACGILL-EAIN BIBLIOGRAPHY POETICAL WORKS 1940 MacLean, S. and Garioch, Robert. 17 Poems for 6d. Edinburgh: Chalmers Press, 1940. MacLean, S. and Garioch, Robert. Seventeen Poems for Sixpence [second issue with corrections]. Edinburgh: Chalmers Press, 1940. 1943 MacLean, S. Dàin do Eimhir agus Dàin Eile. Glasgow: William MacLellan, 1943. 1971 MacLean, S. Poems to Eimhir, translated from the Gaelic by Iain Crichton Smith. London: Victor Gollancz, 1971. MacLean, S. Poems to Eimhir, translated from the Gaelic by Iain Crichton Smith. (Northern House Pamphlet Poets, 15). Newcastle upon Tyne: Northern House, 1971. 1977 MacLean, S. Reothairt is Contraigh: Taghadh de Dhàin 1932-72 /Spring tide and Neap tide: Selected Poems 1932-72. Edinburgh: Canongate, 1977. 1987 MacLean, S. Poems 1932-82. Philadelphia: Iona Foundation, 1987. 1989 MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh / From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and English. Manchester: Carcanet, 1989. 1991 MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh/ From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and English. London: Vintage, 1991. 1999 MacLean, S. Eimhir. Stornoway: Acair, 1999. MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh/From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and in English translation. Manchester and Edinburgh: Carcanet/Birlinn, 1999. 2002 MacLean, S. Dàin do Eimhir/Poems to Eimhir, ed. Christopher Whyte. Glasgow: Association of Scottish Literary Studies, 2002. MacLean, S. Hallaig, translated by Seamus Heaney. Sleat: Urras Shomhairle, 2002. PROSE WRITINGS 1 1945 MacLean, S. ‘Bliain Shearlais – 1745’, Comar (Nollaig 1945). 1947 MacLean, S. ‘Aspects of Gaelic Poetry’ in Scottish Art and Letters, No. 3 (1947), 37. 1953 MacLean, S. ‘Am misgear agus an cluaran: A Drunk Man looks at the Thistle, by Hugh MacDiarmid’ in Gairm 6 (Winter 1953), 148. -

Artymiuk, Anne

UHI Thesis - pdf download summary Today's No Ground to Stand Upon A Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Artymiuk, Anne DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (AWARDED BY OU/ABERDEEN) Award date: 2019 Awarding institution: The University of Edinburgh Link URL to thesis in UHI Research Database General rights and useage policy Copyright,IP and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UHI Research Database are retained by the author, users must recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement, or without prior permission from the author. Users may download and print one copy of any thesis from the UHI Research Database for the not-for-profit purpose of private study or research on the condition that: 1) The full text is not changed in any way 2) If citing, a bibliographic link is made to the metadata record on the the UHI Research Database 3) You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain 4) You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the UHI Research Database Take down policy If you believe that any data within this document represents a breach of copyright, confidence or data protection please contact us at [email protected] providing details; we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 ‘Today’s No Ground to Stand Upon’: a Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Anne Artymiuk M.A. -

A Caledonian Cacophony: Languages and Literatures of Scotland

A Caledonian Cacophony Languages and Literatures of Scotland Manfred Malzahn Department of English Literature United Arab Emirates University Al Ain, U.A.E. Biannual Conference: Sustainable Multilingualism Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, Lithuania 26-27 May 2017 English Scots Gaelic UK Languages Mapping Twitter @UKLANGMAPPING https://twitter.com/uklangmapping/status/76112836220727705 6 Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig) http://www.omniglot.com/writing/gaelic.htm Ceud mile fàilte. Ciamar a tha thu? Tha mi gu math, tapadh leat. Am bheil Gàidhlig agad? Tha an la fliuch an diugh. Tha am pathadh orm. Slàinte mhath! Bithidh mi a’ dol dhachaidh. Oidhche mhath. Scots (Lallans) http://www.scotslanguage.com Scots History Scots originated with the tongue of the Angles who arrived in Scotland about AD 600, or 1,400 years ago. During the Middle Ages this language developed and grew apart from its sister tongue in England, until a distinct Scots language had evolved. At one time Scots was the national language of Scotland, spoken by Scottish kings, and was used to write the official records of the country. Scots (Lallans) http://www.lallans.co.uk/ http://www.scots-online.org/ Hou’s aw wi ye? Hou’s yer dous? Hou d’ye fend? (SW) Hou ye lestin? (Borders) Whit fettle? (Borders) Whit like? (NE) Whit wey are ye? (Ulster) Whit aboot ye? (Ulster) Brawly—thank ye. No bad, conseederin. A canna compleen. Hingin by a threed. A hae been waur. “Toward a holistic national language policy for Scotland” Mark McConville, Scottish Language34 (2015) pp. 42-57 “Partly as a result of the introduction of obligatory English-medium schooling in 1872, language practices across Scotland were, until recently, characterised by a kind of diglossia, with English being used in high domains, and either Gaelic or Scots being used in low domains.” (45) The Ring of Words. -

1427 to 1453

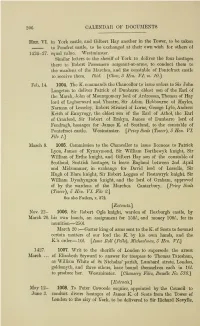

206 CALENDAE OF DOCUMENTS Hen. VI. in York castle, and Gilbert Hay another in the Tower, to be taken to Pomfret castle, to be exchanged at their own wish for others of 1426-27. equal value. Westminster. Similar letters to the sheriff of York to deliver the four hostages there to Eobert Passemere sergeant-at-arms, to conduct them to the wardens of the Marches, and the constable of Pontefract castle to receive them. IMd. {^Closc, 5 Hen. VI. m. JO.] Feb. 14. 1004. The K. commands the Chancellor to issue orders to Sir John Langeton to deliver Patrick of Dunbarre eldest son of the Earl of the March, John of Mountgomery lord of Ardrossan, Thomas of Hay lord of Loghorward and Yhestre, Sir Adam Hebbourne of Hayles, Norman of Lesseley, Eobert Stiward of Lome, George Lyle, Andrew Keith of Ennyrugy, the eldest son of the Earl of Athol, the Earl of Crauford, Sir Eobert of Erskyn, James of Dunbarre lord of Fendragh, hostages for James K. of Scotland, to the constable of Pontefract castle. Westminster. {^Privy Seals (Toiuer), 5 Hen. VI. File I] March 8. 1005. Commission to the Chancellor to issue licences to Patrick Lyon, James of Kynnymond, Sir William Borthewyk knight, Sir William of Erthe knight, and Gilbert Hay son of the constable of Scotland, Scottish hostages, to leave England between 2nd April and Midsummer, in exchange for David lord of Lesselle, Sir Hugh of Blare knight. Sir Eobert Loggan of Eestawryk knight, Sir William Dysshyngton knight, and the lord of Graham, approved of by the wardens of the Marches. -

SCOTTISH TEXT SOCIETY Old Series

SCOTTISH TEXT SOCIETY Old Series Skeat, W.W. ed., The kingis quiar: together with A ballad of good counsel: by King James I of Scotland, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 1 (1884) Small, J. ed., The poems of William Dunbar. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 2 (1883) Gregor, W. ed., Ane treatise callit The court of Venus, deuidit into four buikis. Newlie compylit be Iohne Rolland in Dalkeith, 1575, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 3 (1884) Small, J. ed., The poems of William Dunbar. Vol. II, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 4 (1893) Cody, E.G. ed., The historie of Scotland wrytten first in Latin by the most reuerend and worthy Jhone Leslie, Bishop of Rosse, and translated in Scottish by Father James Dalrymple, religious in the Scottis Cloister of Regensburg, the zeare of God, 1596. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 5 (1888) Moir, J. ed., The actis and deisis of the illustere and vailzeand campioun Schir William Wallace, knicht of Ellerslie. By Henry the Minstrel, commonly known ad Blind Harry. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 6 (1889) Moir, J. ed., The actis and deisis of the illustere and vailzeand campioun Schir William Wallace, knicht of Ellerslie. By Henry the Minstrel, commonly known ad Blind Harry. Vol. II, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 7 (1889) McNeill, G.P. ed., Sir Tristrem, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 8 (1886) Cranstoun, J. ed., The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 9 (1887) Cranstoun, J. ed., The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie. Vol. -

Byron and the Scottish Literary Tradition Roderick S

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 14 | Issue 1 Article 16 1979 Byron and the Scottish Literary Tradition Roderick S. Speer Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Speer, Roderick S. (1979) "Byron and the Scottish Literary Tradition," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 14: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol14/iss1/16 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Roderick S. Speer Byron and the Scottish Literary 1radition It has been over forty years since T. S. Eliot proposed that we consider Byron as a Scottish poet. 1 Since then, anthologies of Scottish verse and histories of Scottish literature seldom neglect to mention, though always cursorily, Byron's rightful place in them. The anthologies typically make brief reference to Byron and explain that his work is so readily available else where it need be included in short samples or not at al1.2 An historian of the Scots tradition argues for Byron's Scottish ness but of course cannot treat a writer who did not use Scots. 3 This position at least disagrees with Edwin Muir's earlier ar gument that with the late eighteenth century passing of Scots from everyday to merely literary use, a Scottish literature of greatness had passed away.4 Kurt -

29 02 16 Leahy on Douglas.03

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of East Anglia digital repository 1 Dreamscape into Landscape in Gavin Douglas CONOR LEAHY More than any other poet of the late Middle Ages Gavin Douglas knew how to describe the wind. It could have a ‘lowde quhissilling’ or a ‘softe piping’; could blow in ‘bubbys thik’ or ‘brethfull blastis’. Its rumbling ‘ventositeis’ could be ‘busteous’ or ‘swyft’ or ‘swouchand’. On the open water, it could ‘dyng’ or ‘swak’ or ‘quhirl’ around a ship; could come ‘thuddand doun’ or ‘brayand’ or ‘wysnand’. At times it could have a ‘confortabill inspiratioun’, and nourish the fields, but more typically it could serve as a harsh leveller, ‘Dasyng the blude in euery creatur’.1 Such winds are whipped up across the landscapes and dreamscapes of Douglas’s surviving poetry, and attest to the extraordinary copiousness of his naturalism. The alliterative tradition was alive and well in sixteenth century Scotland, but as Douglas himself explained, he could also call upon ‘Sum bastard Latyn, French or Inglys’ usages to further enrich ‘the langage of Scottis natioun’.2 Douglas’s translation of Virgil’s Aeneid (1513) has itself occasioned a few blasts of hot air. John Ruskin described it as ‘one of the most glorious books ever written by any nation in any language’ and would often mention Douglas in the same breath as Dante.3 Ezra Pound breezily declared that the Eneados was ‘better than the original, as Douglas had heard the sea’,4 while T.S. -

Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth-Century Scottish Literature," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 35 | Issue 1 Article 12 2007 Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth- Century Scottish Literature Sally Mapstone St. Hilda's College, Oxford Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Mapstone, Sally (2007) "Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth-Century Scottish Literature," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 35: Iss. 1, 131–155. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol35/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sally Mapstone Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth-Century Scottish Literature Among the voluminous papers of William Drummond of Hawthomden, not, however with the majority of them in the National Library of Scotland, but in a manuscript identified about thirty years ago and presently in Dundee Uni versity Library, 1 is a small and succinct record kept by the author of significant events and moments in his life; it is entitled "MEMORIALLS." One aspect of this record puzzled Drummond's bibliographer and editor, R. H. MacDonald. This was Drummond's idiosyncratic use of the term "fatall." Drummond first employs this in the "Memorialls" to describe something that happened when he was twenty-five: "Tusday the 21 of Agust [sic] 1610 about Noone by the Death of my father began to be fatall to mee the 25 of my age" (Poems, p.