Women and Debt Litigation in Seventeenth Century Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North East Scotland

Employment Land Audit 2018/19 Aberdeen City Council Aberdeenshire Council Employment Land Audit 2018/19 A joint publication by Aberdeen City Council and Aberdeenshire Council Executive Summary 1 1. Introduction 1.1 Purpose of Audit 5 2. Background 2.1 Scotland and North East Scotland Economic Strategies and Policies 6 2.2 Aberdeen City and Shire Strategic Development Plan 7 2.3 Aberdeen City and Aberdeenshire Local Development Plans 8 2.4 Employment Land Monitoring Arrangements 9 3. Employment Land Audit 2018/19 3.1 Preparation of Audit 10 3.2 Employment Land Supply 10 3.3 Established Employment Land Supply 11 3.4 Constrained Employment Land Supply 12 3.5 Marketable Employment Land Supply 13 3.6 Immediately Available Employment Land Supply 14 3.7 Under Construction 14 3.8 Employment Land Supply Summary 15 4. Analysis of Trends 4.1 Employment Land Take-Up and Market Activity 16 4.2 Office Space – Market Activity 16 4.3 Industrial Space – Market Activity 17 4.4 Trends in Employment Land 18 Appendix 1 Glossary of Terms Appendix 2 Employment Land Supply in Aberdeen and map of Aberdeen City Industrial Estates Appendix 3 Employment Land Supply in Aberdeenshire Appendix 4 Aberdeenshire: Strategic Growth Areas and Regeneration Priority Areas Appendix 5 Historical Development Rates in Aberdeen City & Aberdeenshire and detailed description of 2018/19 completions December 2019 Aberdeen City Council Aberdeenshire Council Strategic Place Planning Planning and Environment Marischal College Service Broad Street Woodhill House Aberdeen Westburn Road AB10 1AB Aberdeen AB16 5GB Aberdeen City and Shire Strategic Development Planning Authority (SDPA) Woodhill House Westburn Road Aberdeen AB16 5GB Executive Summary Purpose and Background The Aberdeen City and Shire Employment Land Audit provides up-to-date and accurate information on the supply and availability of employment land in the North-East of Scotland. -

From Oil Wealth to Green Growth

From oil wealth to green growth An empirical agent-based model of recession, migration and sustainable urban transition Jiaqi Ge1, Gary Polhill1, Tony Craig1, Nan Liu2 1 The James Hutton Institute 2 University of Aberdeen Abstract This paper develops an empirical, multi-layered and spatially-explicit agent-based model that explores sustainable pathways for Aberdeen City and surrounding area to transition from an oil- based economy to green growth. The model takes an integrated, complex system approach to urban systems and incorporates the interconnectedness between people, households, businesses, industries and neighbourhoods. We find that the oil price collapse could potentially lead to enduring regional decline and recession. With green growth, however, the crisis could be used as an opportunity to restructure the regional economy, reshape its neighbourhoods, and redefine its identity in the global economy. We find that the type of the green growth and the location of the new businesses will have profound ramifications for development outcomes, not only by directly creating businesses and employment opportunities in strategic areas, but also by redirecting households and service businesses to these areas. New residential and business centres emerge as a result of this process. Finally, we argue that industries, businesses and the labour market are essential components of a deeply integrated urban system. To understand urban transition, models should consider both household and industrial aspects. Highlights • An empirical, multi-layered -

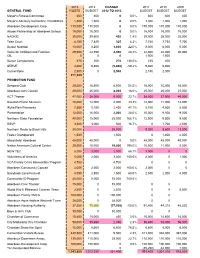

2013 2012 Change 2011 2010 2009 General Fund Rqstd

2013 2012 CHANGE 2011 2010 2009 GENERAL FUND RQSTD BUDGET 2012 TO 2013 BUDGET BUDGET BUDGET Mayor's Fitness Committee 600 600 0 0.0% 600 600 600 Mayor's Advisory Committee / Disabilities 1,300 1,300 0 0.0% 1,300 1,000 1,000 Aberdeen Development Corp. 170,000 170,000 0 0.0% 170,000 170,000 170,000 Abuse Partnership w/ Aberdeen School 15,000 15,000 0 0.0% 15,000 15,000 15,000 NADRIC 30,000 29,600 400 1.4% 29,000 28,000 25,000 Teen Court 8,150 7,825 325 4.2% 7,740 7,735 7,700 Senior Nutrition 10,000 8,200 1,800 22.0% 8,000 6,000 5,000 Voice for Children and Families 29,500 24,550 4,950 20.2% 24,000 22,000 20,000 OIL 0 0 0 1,500 1,500 Senior Companions 470 200 270 135.0% 425 400 SERVE 4,000 9,800 (5,800) -59.2% 9,600 9,600 Cornerstone 2,500 0 2,500 2,150 2,000 271,520 PROMOTION FUND Sertoma Club 25,000 16,500 8,500 51.5% 16,000 15,000 16,000 Aberdeen Arts Council 29,000 25,000 4,000 16.0% 25,000 25,000 27,000 ACT Theater 47,000 38,000 9,000 23.7% 38,000 37,000 40,000 Dacotah Prairie Museum 16,000 12,000 4,000 33.3% 12,000 11,000 12,000 Wylie Park Fireworks 7,500 5,100 2,400 47.1% 5,100 4,600 5,500 Presentation 12,000 10,000 2,000 20.0% 10,000 9,500 9,500 Northern State Foundation 40,000 15,000 25,000 166.7% 12,500 9,500 9,500 RSVP 3,500 3,000 500 16.7% 0 1,700 2,500 Northern Route to Black Hills 25,000 25,000 9,000 8,600 13,000 Foster Grandparent 1,500 1,500 0 1,400 2,000 Absolutely! Aberdeen 48,000 48,000 0 0.0% 48,000 48,000 40,000 Native American Cultural Center 29,500 10,000 19,500 195.0% 10,000 11,000 5,000 NEW TEC 5,000 3,000 2,000 -

OFFICIAL GUIDE for Winches and Deck Machinery Torque to the Experts Engineering Services Ltd

OFFICIAL GUIDE For winches and deck machinery torque to the experts Engineering Services Ltd Belmar Engineering is one of the most advanced sub contract precision engineering workshops servicing the Oil and Gas industries in the North Sea and world-wide. An imaginative and on-going programme of reinvestment in computer based technology has meant that Belmar Engineering work at the very frontiers of technology. We are quite simply the most precise of precision engineering companies. Our Services Belmar offer a complete engineering service to BS EN ISO 9001(2000) and ISO 14001(2004). Please visit our website for detailed pages of machining capacities, inspection and gauges below: Milling Section. Turning Section. Machine shop support. Quality Assurance. Weld cladding equipment. The Deck Machinery Specialists: ACE Winches is a global specialist in the design, Engineering design & project management manufacture and hire of hydraulic winches and deck machinery for the offshore oil and gas, All sizes of winches for sale & hire marine and renewable energy markets. Bespoke manufacturing solutions available Specialist offshore personnel hire We deliver exceptional service and performance for our clients in the world’s harshest operating environments and we always endeavour to Hydraulic sales & service exceed our clients’ expectations while maintaining our excellent record of quality and safety. Spooling winch hire About us How we operate Our people 750 tonne winch test bed facility ACE Hire Equipment offers a comprehensive range of winch and deck machinery equipment for use on floating vessels, offshore installations Wire rope & umbilical spooling facility Belmar offers a comprehensive Belmar Engineering was formed in One third of our workforce have and land-based projects. -

Aberdeen Harbour Masterplan 2020 Contents

ABERDEEN HARBOUR MASTERPLAN 2020 CONTENTS Introduction 4 Conclusion and Next Steps 78 Executive summary 6 Appendix Vision 8 Purpose 10 Please refer to separate document Energy transition 12 Economic Context 14 Analysis and opportunity 16 Economic opportunity 22 Masterplan Proposition 28 Planning and technical overview 30 Consolidated constraints 36 Consolidated opportunities 38 Precedent studies 40 Aberdeen Harbour timeline 46 Design strategies 54 Masterplan and Character Areas 66 Economic benefits summary 70 Aberdeen Harbour Vision 2050 76 2 ABERDEEN HARBOUR Masterplan 2020 3 INTRODUCTION Executive Summary Vision Purpose 01 Energy Transition 4 ABERDEEN HARBOUR Masterplan 2020 DDaattaa SSIIOO,, NNOOAAAA,, UU..SS.. NNaavvyy,, NNGGAA,, GGEEBBCCOO Data SIO, NOAA, U.S. Navy, NGA, GEBCO Aerial Map 5 DDaattaa SSIIOO,, NNOOAAAA,, UU..SS.. NNaavvyy,, NNGGAA,, GGEEBBCCOO Data SIO, NOAA, U.S. Navy, NGA, GEBCO EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Aberdeen Harbour is Europe’s premier marine support centre for the energy industry and the main commercial port serving North East Scotland. The harbour was founded in 1136, and with a near-900 year history, is the oldest existing business in the UK. This document sets out our vision for the future of Aberdeen Harbour. It is an ambitious and transformational vision which articulates how we will continue to diversify our business and lead Scotland’s energy transition from oil and gas over the next 30 years to 2050 and beyond. There is an economic and environmental imperative in Scotland to diversify from North Sea oil and gas to meet the Scottish Government’s target of Net Zero Carbon by 2045. This shift to diversify our economy and reduce Scotland’s environmental footprint will require significant commitment, investment and collaboration between the public and private sectors and Aberdeen Harbour has a pivitol role to play. -

Response from Nestrans to Discussion Paper No.6: Utilising the UK’S Existing Airport Capacity

Airports Commission 6th Floor Sanctuary Buildings 20 Great Smith Street London SW1P 3BT 25 July 2014 Dear Sir, Response From Nestrans to Discussion Paper No.6: Utilising the UK’s Existing Airport Capacity. This submission is based upon an ‘update’ of an original Evidence Note on Air Links to London from the North of Scotland, commissioned jointly by Nestrans and HITRANS and first published in May 2012. A copy of that document was sent to the Airports Commission in March 2013, and was subsequently used by the two strategic transport partnerships to underpin submissions made to the Commission in response to its various ‘calls for evidence’ and discussion papers during the spring and summer of 2013. The ‘refresh’ of the Evidence Note, which forms the basis of this response to the Commission’s Discussion Paper No6, uses the latest 2013 CAA survey data for Scottish airports, whereas the earlier document had to rely on 2009 data. It also includes an up- dated policy overview, because there have been a number of significant developments in this regard in the intervening period and contains feedback from interviews with several important business figures in the North of Scotland about the importance of air links to London in serving their sector of the region’s economy. The full, recently completed, Update document can be found at: http://www.nestrans.org.uk/air- links-to-london-from-the-north-of-scotland.html Policy Update UK regional aviation policy exhibits some recent welcome signs of change: Flybe intervened - with Government support - to add additional flights to London from Newquay at regular fare levels, while the train services linking Cornwall to the capital were disrupted, and Government changed its long-running ambivalence to PSOs with the capital to keep the service running to its traditional home at Gatwick. -

Technical Appendix to Socio-Economic and Tourism Report

ABERDEEN HARBOUR EXPANSION PROJECT November 2015 Volume 3: Technical Appendices APPENDIX 16-B ECONOMIC IMPACT OF ABERDEEN HARBOUR NIGG BAY DEVELOPMENT - TECHNICAL APPENDIX TO SOCIO-ECONOMIC AND TOURISM REPORT BiGGAR Economics Economic impact of Aberdeen Harbour Nigg Bay Development Technical appendix to socio-economic and tourism report st 21 October 2015 BiGGAR Economics Midlothian Innovation Centre Pentlandfield Roslin, Midlothian EH25 9RE 0131 440 9032 [email protected] www.biggareconomics.co.uk This Project has received funding from the European Union: The Content of the Document does not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of the EU Commission and that the Commission is not responsible for any use made by any party of the information contained within it. CONTENTS Page 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................... 1 2 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 3 3 MARKET CONTEXT ............................................................................................. 4 4 APPROACH ........................................................................................................ 11 5 BASELINE ECONOMIC ANALYSIS ................................................................... 14 6 ASSUMPTIONS ABOUT FUTURE DEVELOPMENT ......................................... 25 7 FUTURE ECONOMIC IMPACT ........................................................................... 36 8 SUMMARY AND -

(Private Pack)Agenda Document for Community Planning Aberdeen

Meeting on TUESDAY, 26 FEBRUARY 2019 at 2.00 pm **Committee Room 2 - Town House, Aberdeen** B U S I N E S S APOLOGIES AND INTRODUCTIONS DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST 1.1 Partners are requested to intimate any declarations of interest MINUTES AND FORWARD BUSINESS PLANNER 2.1 Minute of Previous Meeting of 3 December 2018 - for approval (Pages 3 - 12) 2.2 CPA Board Forward Business Planner (Pages 13 - 14) 2.3 National Update, Scottish Government (verbal update from Neil Rennick) LOCAL OUTCOME IMPROVEMENT PLAN/LOCALITY PLANNING 3.1 Refreshed Aberdeen City Local Outcome Improvement Plan 2016-26 (Pages 15 - 90) 3.2 Update on Leadership of Outcome Improvement Groups (Pages 91 - 92) 3.3 Innovate and Improve Programme (Pages 93 - 122) GENERAL BUSINESS 4.1 Fairer Aberdeen Fund Annual Report (Pages 123 - 142) 4.2 Child Friendly Cities (Pages 143 - 198) FOR YOUR INFORMATION 4.3 Aberdeen Health and Social Care Partnership and Aberdeen City Council Autism Strategy (Pages 199 - 234) 4.4 Date of Next Meeting - 1 May 2019 at 2pm Should you require any further information about this agenda, please contact Allison Swanson, tel. 01224 522822 or email [email protected] COMMUNITY PLANNING ABERDEEN BOARD 3 DECEMBER 2018 Present:- Councillor Laing, Chair, Campbell Thomson, Vice Chair (Police Scotland), Councillor Wheeler, Jillian Evans (as a substitute for Susan Webb) (Public Health), Gordon MacDougall (Skills Development Scotland), Ken Milroy (North East College), Neil Rennick (Scottish Government) via conference call, Darren Riddell (as a substitute for Bruce Farquharson) (Scottish Fire and Rescue Service), Angela Scott (Aberdeen City Council (ACC), Jonathan Smith (Civic Forum). -

Statoil-Socio-Economic Impact Assessment

Hywind Scotland Pilot Park Project – Assessment of socio-economic indicators and Impacts Enquiry No. 027063 Hywind (Scotland) Limited Draft Report August 2014 Confidential Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................... 1 1.1 Scope of the assessment ............................................................................. 1 1.2 Methodology............................................................................................... 1 Sources of Impact .................................................................................................... 2 Additionality ............................................................................................................ 2 1.2.1 Direct and supply chain economic baseline and potential impacts ........................ 4 1.2.2 Tourism and recreation baseline and potential impacts ....................................... 7 1.2.3 Assessment criteria ....................................................................................... 9 1.3 Summary of relevant consultations and activities .......................................... 11 1.4 Policy and strategic context ........................................................................ 12 2. Socio-economic baseline ................................................................ 13 2.1 Socio-economic baseline ............................................................................ 13 2.1.1 Comparison of key indicators ....................................................................... -

Aberdeen City and Shire Hotel Accommodation Report

Scottish Enterprise Aberdeen City and Shire Hotel Accommodation Report July 2009 Contents 1. Executive Summary 2 2. Introduction 4 3. Overview of Aberdeen City and Shire Market 6 4. Key Developments in Tourism and Infrastructure 8 5. The Conference Market in Aberdeen City and Shire 12 6. Current and Proposed Hotel Development 14 7. Conclusion 16 Appendices: Appendix 1: Aberdeen City and Shire Hotel & Resort Development Opportunities 18 Appendix 2: Reasons for lost business 07/08 26 Appendix 3: Business lost as a result of accommodation issues 08/09 27 Images courtesy of www.aberdeencityandshire.com 1. Executive Summary This report is the second edition of Scottish Enterprise’s hotel accommodation report, and supersedes the November 2008 report. It is prepared for property developers and investors, local authorities, Scottish Development International, and other parties with an interest in hotel and accommodation development in Aberdeen City and Shire. The report presents an overview of the Aberdeen City and Shire market for both the business and leisure market, and highlights the current supply and demand of hotel stock as well as existing opportunities – short, medium and long-term - for investors, developers and operators. Since the last report there has been significant forward momentum. The tables below show new hotels, hotels under construction or in planning and other major investment projects. New hotels opened in Aberdeen City since November 2008: Hotel Location No. of bedrooms Malmaison West end Aberdeen City 79 Holiday Inn Express Aberdeen Exhibition Centre Bridge of Don 135 TOTAL 214 Hotels in Aberdeen City currently under construction: Hotel Location No. -

Aberdeen Project

Aberdeen Offshore Wind Farm: Socio-Economic Impacts Monitoring Study Technical Report 4: European Offshore Wind Deployment Centre (EOWDC) (Aberdeen Offshore Wind Farm): Socio-Economic Impacts Monitoring Study Final Report John Glasson, Bridget Durning, Tokunbo Olorundami and Kellie Welch Impacts Assessment Unit, Oxford Brookes University https://doi.org/10.24384/v8nf-ja69 1 Aberdeen Offshore Wind Farm: Socio-Economic Impacts Monitoring Study Contents Executive Summary 3 PART A: INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW 5 1. Research approach 5 PART B: EOWDC ECONOMIC IMPACTS 9 2. ES economic impact predictions 9 3. Actual economic impacts – pre-construction 10 4. Actual economic impacts – construction overview 11 5. Actual economic Impacts – construction onshore 12 6. Actual economic Impacts – construction offshore 14 7. Actual economic Impacts – operation and maintenance 16 PART C: EOWDC SOCIAL IMPACTS 18 8. Social impacts – ES predictions 18 9. Actual social impacts – pre-construction 18 10. Actual social impacts – construction stage 22 11. Actual social impacts – operation and management stage 29 PART D : ABERDEENSHIRE FLOATING OFFSHORE WIND FARM 35 COMPARATIVE SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACT STUDIES 12. Introduction 35 13. Hywind Scotland Pilot Park Project (off Peterhead) 35 14. Kincardine Offshore Windfarm 38 PART E: CONCLUSIONS 42 15. Conclusions on the EOWDC (Aberdeen) OWF socio-economic 42 impacts 16. Conclusions on comparative projects and cumulative impacts 46 References 50 Appendices — in separate volume 2 Aberdeen Offshore Wind Farm: Socio-Economic Impacts Monitoring Study Executive Summary Aims: This study is one element of the European Offshore Wind Deployment Centre (EOWDC) Environmental Research and Monitoring Programme supported by Vattenfall. The focus of this element of the whole programme is on the socio-economic impacts of Offshore Wind Farm (OWF) projects on the human environment. -

Proposed Aberdeen Local Development Plan 2020

Proposed Aberdeen Local Development Plan 2020 1 2 Aberdeen Local Development Plan - Proposed Plan Section Content Page Forewords 1. A Sustainable Vision for Aberdeen 2. How to use this Plan National Planning Framework for Scotland Aberdeen City and Shire Strategic Development Plan Aberdeen Local Development Plan – Working Towards the Vision 3. The Spatial Strategy Overview Brownfield Sites Greenfield Development Land Release Delivery of Mixed Communities Directions for Growth Bridge of Don/ Grandhome, Dyce, Bucksburn and Woodside Kingswells and Greenferns, Countesswells Deeside, Loirston and Cove 4. Monitoring and Review – Infrastructure Planning and Delivery 1. Infrastructure Requirements for Masterplan Zones 2. Monitoring Infrastructure and Development Delivery Policy Areas 5. Health and Wellbeing 6. Protecting and Enhancing the Natural Environment 7. Quality Placemaking by Design 8. Using Resources Sustainably 9. Meeting Housing and Community Needs 10. The Vibrant City 11. Delivering Infrastructure, Transport and Accessibility 12. Supporting Business and Industrial Development 13. Glossary 14. Appendices 1. Brownfield Sites 2. Opportunity Sites 3. Masterplan Zones 4. Supplementary Guidance (SG) and Aberdeen Planning Guidance (APG) 5. Schedule of Land Owned by Local Authority 3 Policy Areas Section Policy Page 3. The Spatial Strategy LR1 Land Release Policy LR2 Delivery of Mixed Use Communities 5. Health and Wellbeing WB1 Healthy Developments WB2 Air Quality WB3 Noise WB4 Specialist Care Facilities WB5 Changing Place Toilets 6. Protecting and Enhancing the Natural Environment NE1 Green Belt NE2 Green and Blue Infrastructure NE3 Our Natural Heritage NE4 Our Water Environment NE5 Trees and Woodland 7. Quality Placemaking by Design D1 Quality Placemaking D2 Amenity D3 Big Buildings D4 Landscape D5 Landscape Design D6 Historic Environment D7 Our Granite Heritage D8 Windows and Doors D9 Shopfronts 8.