Highland Emigration to Nova Scotia *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Services Contact List

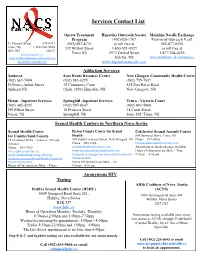

Services Contact List Opiate Treatment Hepatitis Outreach Society Mainline Needle Exchange Program (902)420-1767 Provincial Outreach # call 33 Pleasant Street, 895-0931 (902) 893-4776 or toll free at 902-877-0555 Truro, NS 1 866-940-AIDS 332 Willow Street 1-800-521-0527 or toll free at B2N 3R5 (2437) [email protected] Truro NS 2973 Oxford Street 1-877-904-4555 www.northernaidsconnectionsociety.ca Halifax, NS www.mainlineneedleexchange.ca facebook.com/nacs.ns www.hepatitisoutreach.com Addiction Services Amherst- East Hants Resource Center New Glasgow Community Health Center (902) 667-7094 (902) 883-0295 (902) 755-7017 30 Prince Arthur Street 15 Commerce Court 835 East River Road Amherst,NS (Suite #250) Elmsdale, NS New Glasgow, NS Pictou - Inpatient Services Springhill -Inpatient Services Truro - Victoria Court (902) 485-4335 (902) 597-8647 (902) 893-5900 199 Elliott Street 10 Princess Street 14 Court Street, Pictou, NS Springhill, NS Suite 205, Truro, NS Sexual Health Centers in Northern Nova Scotia Sexual Health Center Pictou County Center for Sexual Colchester Sexual Assault Center for Cumberland County Health 80 Glenwood Drive, Truro, NS 11 Elmwood Drive , Amherst , NS side 503 South Frederick Street, New Glasgow, NS Phone 897-4366 entrance Phone 695-3366 [email protected] Phone 667-7500 [email protected] No website or facebook page available [email protected] www.pictoucountysexualhealth.com Hours of Operation are Mon. - Thur. www.cumberlandcounty.cfsh.info facebook.com/pages/pictou-county-centre-for- 9:30am – 4:30 pm facebook.com/page/Sexual-Health-Centre-for- Sexual-Health Cumberland-County Hours of Operation are Mon. -

NS Royal Gazette Part I

Nova Scotia Published by Authority PART 1 VOLUME 220, NO. 4 HALIFAX, NOVA SCOTIA, WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 26, 2011 Land Transactions by the Province of Schedule “A” Nova Scotia pursuant to the Ministerial Notice of Parcel Registration under the Land Transaction Regulations (MLTR) for Land Registration Act the period February 13, 2009 to October 14, 2010 TAKE NOTICE that ownership of the property known as Name/Grantor Year Fishery Limited PID 20244828, located at 700 Willow Street, Truro, Type of Transaction Grant Colchester County, Nova Scotia, has been registered Location Hacketts Cove under the Land Registration Act, in whole or in part on Halifax County the basis of adverse possession, in the name of Allen Area 1195 square metres Dexter Symes. Document Number 92763250 recorded February 13, 2009 NOTICE is being provided as directed by the Registrar General of Land Titles in accordance with clause Name/Grantor Mariners Anchorage Residents 10(10)(b) of the Land Registration Administration Association Regulations. For further information, you may contact Type of Transaction Grant the lawyer for the registered owner, noted below. Location Glen Haven, Halifax County Area 192 square metres TO: The Heirs of Ernest MacKenzie or other persons Document Number 96826046 who may have an interest in the above-noted property. recorded September 21, 2010 DATED at Pictou, Pictou County, Nova Scotia, this Name/Grantor Welsford, Barbara 17th day of January, 2011. Type of Transaction Grant Location Oakland, Halifax County Ian H. MacLean Area 174 square metres -

North East Scotland

Employment Land Audit 2018/19 Aberdeen City Council Aberdeenshire Council Employment Land Audit 2018/19 A joint publication by Aberdeen City Council and Aberdeenshire Council Executive Summary 1 1. Introduction 1.1 Purpose of Audit 5 2. Background 2.1 Scotland and North East Scotland Economic Strategies and Policies 6 2.2 Aberdeen City and Shire Strategic Development Plan 7 2.3 Aberdeen City and Aberdeenshire Local Development Plans 8 2.4 Employment Land Monitoring Arrangements 9 3. Employment Land Audit 2018/19 3.1 Preparation of Audit 10 3.2 Employment Land Supply 10 3.3 Established Employment Land Supply 11 3.4 Constrained Employment Land Supply 12 3.5 Marketable Employment Land Supply 13 3.6 Immediately Available Employment Land Supply 14 3.7 Under Construction 14 3.8 Employment Land Supply Summary 15 4. Analysis of Trends 4.1 Employment Land Take-Up and Market Activity 16 4.2 Office Space – Market Activity 16 4.3 Industrial Space – Market Activity 17 4.4 Trends in Employment Land 18 Appendix 1 Glossary of Terms Appendix 2 Employment Land Supply in Aberdeen and map of Aberdeen City Industrial Estates Appendix 3 Employment Land Supply in Aberdeenshire Appendix 4 Aberdeenshire: Strategic Growth Areas and Regeneration Priority Areas Appendix 5 Historical Development Rates in Aberdeen City & Aberdeenshire and detailed description of 2018/19 completions December 2019 Aberdeen City Council Aberdeenshire Council Strategic Place Planning Planning and Environment Marischal College Service Broad Street Woodhill House Aberdeen Westburn Road AB10 1AB Aberdeen AB16 5GB Aberdeen City and Shire Strategic Development Planning Authority (SDPA) Woodhill House Westburn Road Aberdeen AB16 5GB Executive Summary Purpose and Background The Aberdeen City and Shire Employment Land Audit provides up-to-date and accurate information on the supply and availability of employment land in the North-East of Scotland. -

Troutquest Guide to Trout Fishing on the Nc500

Version 1.2 anti-clockwise Roger Dowsett, TroutQuest www.troutquest.com Introduction If you are planning a North Coast 500 road trip and want to combine some fly fishing with sightseeing, you are in for a treat. The NC500 route passes over dozens of salmon rivers, and through some of the best wild brown trout fishing country in Europe. In general, the best trout fishing in the region will be found on lochs, as the feeding is generally richer there than in our rivers. Trout fishing on rivers is also less easy to find as most rivers are fished primarily for Atlantic salmon. Scope This guide is intended as an introduction to some of the main trout fishing areas that you may drive through or near, while touring on the NC500 route. For each of these areas, you will find links to further information, but please note, this is not a definitive list of all the trout fishing spots on the NC500. There is even more trout fishing available on the route than described here, particularly in the north and north-west, so if you see somewhere else ‘fishy’ on your trip, please enquire locally. Trout Fishing Areas on the North Coast 500 Route Page | 2 All Content ©TroutQuest 2017 Version 1.2 AC Licences, Permits & Methods The legal season for wild brown trout fishing in the UK runs from 15th March to 6th October, but most trout lochs and rivers in the Northern Highlands do not open until April, and in some cases the beginning of May. There is no close season for stocked rainbow trout fisheries which may be open earlier or later in the year. -

North Highlands North Highlands

Squam Lakes Natural Science Center’s North Highlands Wester Ross, Sutherland, Caithness and Easter Ross June 14-27, 2019 Led by Iain MacLeod 2019 Itinerary Join native Scot Iain MacLeod for a very personal, small-group tour of Scotland’s Northern Highlands. We will focus on the regions known as Wester Ross, Sutherland, Caithness and Easter Ross. The hotels are chosen by Iain for their comfort, ambiance, hospitality, and excellent food. Iain personally arranges every detail—flights, meals, transportation and daily destinations. Note: This is a brand new itinerary, so we will be exploring this area together. June 14: Fly from Logan Airport, Boston to Scotland. I hope that we will be able to fly directly into Inverness and begin our trip from there. Whether we fly through London, Glasgow or Dublin will be determined later in 2018. June 15: Arrive in Inverness. We will load up the van and head west towards the spectacular west coast passing by Lochluichart, Achnasheen and Kinlochewe along the way. We will arrive in the late afternoon at the Sheildaig Lodge Hotel (http://www.shieldaiglodge.com/) which will be our base for four nights. June 16-18: We will explore Wester Ross. Highlights will include Beinn Eighe National Nature Reserve, Inverewe Gardens, Loch Torridon and the Torridon Countryside Center. We’ll also take a boat trip out to the Summer Isles on Shearwater Summer Isle Cruises out of Ullapool. We’ll have several opportunities to see White-tailed Eagles, Golden Eagles, Black-throated Divers as well as Otters and Seals. June 19: We’ll head north along the west coast of Wester Ross and Sutherland past Loch Assynt and Ardvreck Castle, all the way up tp the north coast. -

From Oil Wealth to Green Growth

From oil wealth to green growth An empirical agent-based model of recession, migration and sustainable urban transition Jiaqi Ge1, Gary Polhill1, Tony Craig1, Nan Liu2 1 The James Hutton Institute 2 University of Aberdeen Abstract This paper develops an empirical, multi-layered and spatially-explicit agent-based model that explores sustainable pathways for Aberdeen City and surrounding area to transition from an oil- based economy to green growth. The model takes an integrated, complex system approach to urban systems and incorporates the interconnectedness between people, households, businesses, industries and neighbourhoods. We find that the oil price collapse could potentially lead to enduring regional decline and recession. With green growth, however, the crisis could be used as an opportunity to restructure the regional economy, reshape its neighbourhoods, and redefine its identity in the global economy. We find that the type of the green growth and the location of the new businesses will have profound ramifications for development outcomes, not only by directly creating businesses and employment opportunities in strategic areas, but also by redirecting households and service businesses to these areas. New residential and business centres emerge as a result of this process. Finally, we argue that industries, businesses and the labour market are essential components of a deeply integrated urban system. To understand urban transition, models should consider both household and industrial aspects. Highlights • An empirical, multi-layered -

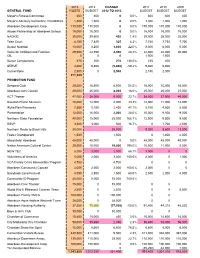

2013 2012 Change 2011 2010 2009 General Fund Rqstd

2013 2012 CHANGE 2011 2010 2009 GENERAL FUND RQSTD BUDGET 2012 TO 2013 BUDGET BUDGET BUDGET Mayor's Fitness Committee 600 600 0 0.0% 600 600 600 Mayor's Advisory Committee / Disabilities 1,300 1,300 0 0.0% 1,300 1,000 1,000 Aberdeen Development Corp. 170,000 170,000 0 0.0% 170,000 170,000 170,000 Abuse Partnership w/ Aberdeen School 15,000 15,000 0 0.0% 15,000 15,000 15,000 NADRIC 30,000 29,600 400 1.4% 29,000 28,000 25,000 Teen Court 8,150 7,825 325 4.2% 7,740 7,735 7,700 Senior Nutrition 10,000 8,200 1,800 22.0% 8,000 6,000 5,000 Voice for Children and Families 29,500 24,550 4,950 20.2% 24,000 22,000 20,000 OIL 0 0 0 1,500 1,500 Senior Companions 470 200 270 135.0% 425 400 SERVE 4,000 9,800 (5,800) -59.2% 9,600 9,600 Cornerstone 2,500 0 2,500 2,150 2,000 271,520 PROMOTION FUND Sertoma Club 25,000 16,500 8,500 51.5% 16,000 15,000 16,000 Aberdeen Arts Council 29,000 25,000 4,000 16.0% 25,000 25,000 27,000 ACT Theater 47,000 38,000 9,000 23.7% 38,000 37,000 40,000 Dacotah Prairie Museum 16,000 12,000 4,000 33.3% 12,000 11,000 12,000 Wylie Park Fireworks 7,500 5,100 2,400 47.1% 5,100 4,600 5,500 Presentation 12,000 10,000 2,000 20.0% 10,000 9,500 9,500 Northern State Foundation 40,000 15,000 25,000 166.7% 12,500 9,500 9,500 RSVP 3,500 3,000 500 16.7% 0 1,700 2,500 Northern Route to Black Hills 25,000 25,000 9,000 8,600 13,000 Foster Grandparent 1,500 1,500 0 1,400 2,000 Absolutely! Aberdeen 48,000 48,000 0 0.0% 48,000 48,000 40,000 Native American Cultural Center 29,500 10,000 19,500 195.0% 10,000 11,000 5,000 NEW TEC 5,000 3,000 2,000 -

Wester Ross Ros An

Scottish Natural Heritage Explore for a day Wester Ross Ros an lar Wester Ross has a landscape of incredible beauty and diversity Historically people have settled along the seaboard, sustaining fashioned by a fascinating geological history. Mountains of strange, themselves by combining cultivation and rearing livestock with spectacular shapes rise up from a coastline of diverse seascapes. harvesting produce from the sea. Crofting townships, with their Wave battered cliffs and crevices are tempered by sandy beaches small patch-work of in-bye (cultivated) fields running down to the or salt marsh estuaries; fjords reach inland several kilometres. sea can be found along the coast. The ever changing light on the Softening this rugged landscape are large inland fresh water lochs. landscape throughout the year makes it a place to visit all year The area boasts the accolade of two National Scenic Area (NSA) round. designations, the Assynt – Coigach NSA and Wester Ross NSA, and three National Nature Reserves; Knockan Crag, Corrieshalloch Symbol Key Gorge and Beinn Eighe. The North West Highland Geopark encompasses part of north Wester Ross. Parking Information Centre Gaelic dictionary Paths Disabled Access Gaelic Pronunciation English beinn bayn mountain gleann glyown glen Toilets Wildlife watching inbhir een-er mouth of a river achadh ach-ugh field mòr more big beag bake small Refreshments Picnic Area madainn mhath mat-in va good morning feasgar math fess-kur ma good afternoon mar sin leat mar shin laht goodbye Admission free unless otherwise stated. 1 11 Ullapool 4 Ullapul (meaning wool farm or Ulli’s farm) This picturesque village was founded in 1788 as a herring processing station by the British Fisheries Association. -

OFFICIAL GUIDE for Winches and Deck Machinery Torque to the Experts Engineering Services Ltd

OFFICIAL GUIDE For winches and deck machinery torque to the experts Engineering Services Ltd Belmar Engineering is one of the most advanced sub contract precision engineering workshops servicing the Oil and Gas industries in the North Sea and world-wide. An imaginative and on-going programme of reinvestment in computer based technology has meant that Belmar Engineering work at the very frontiers of technology. We are quite simply the most precise of precision engineering companies. Our Services Belmar offer a complete engineering service to BS EN ISO 9001(2000) and ISO 14001(2004). Please visit our website for detailed pages of machining capacities, inspection and gauges below: Milling Section. Turning Section. Machine shop support. Quality Assurance. Weld cladding equipment. The Deck Machinery Specialists: ACE Winches is a global specialist in the design, Engineering design & project management manufacture and hire of hydraulic winches and deck machinery for the offshore oil and gas, All sizes of winches for sale & hire marine and renewable energy markets. Bespoke manufacturing solutions available Specialist offshore personnel hire We deliver exceptional service and performance for our clients in the world’s harshest operating environments and we always endeavour to Hydraulic sales & service exceed our clients’ expectations while maintaining our excellent record of quality and safety. Spooling winch hire About us How we operate Our people 750 tonne winch test bed facility ACE Hire Equipment offers a comprehensive range of winch and deck machinery equipment for use on floating vessels, offshore installations Wire rope & umbilical spooling facility Belmar offers a comprehensive Belmar Engineering was formed in One third of our workforce have and land-based projects. -

May 2019 Staffing Assynt Foundation (AF) Is Currently Going Through a Period of Staff Re-Structuring

Assynt Foundation - News For Associate Members - May 2019 Staffing Assynt Foundation (AF) is currently going through a period of staff re-structuring. Rachael and Sam Hawkins have moved on from Glencanisp where they spent 2 years providing high quality hospitality in the Lodge. Jane Tulloch has stepped down as a director of Assynt Foundation and has taken up the position of Lodge Manager until the end of this season. Rebecca Macleod is the Administrator and Stuart Belshaw is the Estate Worker for the Foundation. Glencanisp Lodge The Lodge is being run as a Bed and Breakfast establishment for this summer along with special events such as the recent car rally. Conservation and Deer The deer - management on Glencanisp and Drumrunie for the coming season has been leased to a contractor. He and his team will also carry out the Habitat Impact Assessment which is part of the West Sutherland Deer Management Group South Sub-Group’s plan (available on their website). AF has applied to the Agri-Environment Climate Scheme for Moorland Management. This will cover 13,635 hectares (33,700 acres or about three-quarters of our land) and is for the conservation of peatland and restoration of blanket bog on both estates. The new native woodland establishment at Ledbeg continues where the local planting team are planting broadleaves on the site of a wood that was there in 1774. The south side of Loch Assynt is under consideration for new planting which will try to link all the bits of existing woods there. AF is grateful for help from Coigach and Assynt Living Landscape and The Woodland Trust with the moorland and woodland work. -

KNOYDART a Two-Day Bothy Adventure in the Wilderness of the Rough Bounds

KNOYDART A two-day bothy adventure in the wilderness of the Rough Bounds Overview The so-called 'Rough Bounds' of Knoydart – often described as Britain's last wilderness – are difficult to reach. Getting to the start of the route involves either a boat trip or long car journey along a winding, 20 mile single-track road. Cut off from the UK road network, the peninsula is a wild place of rugged mountains, remote glens and fjord-like sea lochs. This spectacular area includes three Munros and its coastal views take in Skye and the islands of the Inner Hebrides. In the 19th century, the peninsula fell victim to the Highland clearances but since 1999, after huge fundraising efforts, the land has been owned and managed by its own small community. Some days you won’t bump into another soul in here – although you may spot minke whales, eagles, otters and stags. Despite its inaccessibility, there are good paths connecting the glens and these provide exceptional running through challenging terrain. This fastpacking circuit is a wonderful way to immerse yourself in the unique landscape. Highlights • A truly special wilderness experience in a remote and spectacular location • A superb route on a legacy network of well-made paths through wild terrain • Spectacular views of rugged mountain and coastal scenery • Plentiful wildlife including red deer, otters, pine martens and birds of prey such as golden eagles • An overnight stay or wild camp at Sourlies bothy • Fantastic running, descending off the passes and along loch-side paths. Top tips • Be prepared for a serious run in a remote area with limited escape options. -

330 Pictou Antigonish Highlands Profile

A NOVA SCOTIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES PUBLICATION Ecodistrict Profile Ecological Landscape Analysis Summary Ecodistrict 330: Pictou Antigonish Highlands An objective of ecosystem-based management is to manage landscapes in as close to a natural state as possible. The intent of this approach is to promote biodiversity, sustain ecological processes, and support the long-term production of goods and services. Each of the province’s 38 ecodistricts is an ecological landscape with distinctive patterns of physical features. (Definitions of underlined terms are included in the print and electronic glossary.) This Ecological Landscape Analysis (ELA) provides detailed information on the forest and timber resources of the various landscape components of Pictou Antigonish Highlands Ecodistrict 330. The ELA also provides brief summaries of other land values, such as minerals, energy and geology, water resources, parks and protected areas, wildlife and wildlife habitat. This ecodistrict has been described as an elevated triangle separating the Northumberland Lowlands Ecodistrict 530 of Pictou County from the St. Georges Bay Ecodistrict 520 lowlands of Antigonish County. Generally, the highlands at their summit become a rolling plateau best exemplified by The Keppoch, an area once extensively settled and farmed. The elevation in the ecodistrict is usually 210 to 245 metres above sea level and rises to 300 metres at Eigg Mountain. The total area of Pictou Antigonish Highlands is 133,920 hectares. Private land ownership accounts for 75% of the ecodistrict, 24% is under provincial Crown management, and the remaining 1% includes water bodies and transportation corridors. A significant portion of the highlands was settled and cleared for farming by Scottish settlers beginning in the late 1700s with large communities at Rossfield, Browns Mountain, and on The Keppoch.