The Isle of Lewis & Harris (Chaps. VII & VIII)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inner and Outer Hebrides Hiking Adventure

Dun Ara, Isle of Mull Inner and Outer Hebrides hiking adventure Visiting some great ancient and medieval sites This trip takes us along Scotland’s west coast from the Isle of 9 Mull in the south, along the western edge of highland Scotland Lewis to the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides (Western Isles), 8 STORNOWAY sometimes along the mainland coast, but more often across beautiful and fascinating islands. This is the perfect opportunity Harris to explore all that the western Highlands and Islands of Scotland have to offer: prehistoric stone circles, burial cairns, and settlements, Gaelic culture; and remarkable wildlife—all 7 amidst dramatic land- and seascapes. Most of the tour will be off the well-beaten tourist trail through 6 some of Scotland’s most magnificent scenery. We will hike on seven islands. Sculpted by the sea, these islands have long and Skye varied coastlines, with high cliffs, sea lochs or fjords, sandy and rocky bays, caves and arches - always something new to draw 5 INVERNESSyou on around the next corner. Highlights • Tobermory, Mull; • Boat trip to and walks on the Isles of Staffa, with its basalt columns, MALLAIG and Iona with a visit to Iona Abbey; 4 • The sandy beaches on the Isle of Harris; • Boat trip and hike to Loch Coruisk on Skye; • Walk to the tidal island of Oronsay; 2 • Visit to the Standing Stones of Calanish on Lewis. 10 Staffa • Butt of Lewis hike. 3 Mull 2 1 Iona OBAN Kintyre Islay GLASGOW EDINBURGH 1. Glasgow - Isle of Mull 6. Talisker distillery, Oronsay, Iona Abbey 2. -

Lionel Mission Hall, Lionel, Isle of Lewis, HS2 0XD Property

Lionel Mission Hall, Lionel, Isle of Lewis, HS2 0XD Property Detached church building located in the peaceful village of Lionel, to the north of the Isle of Lewis. With open views surrounding, the property benefits from a wonderful spot and presents a very attractive purchase opportunity and is only a short drive from the main town of Stornoway. Entrance Vestibule: 2.59m x 2.25m Main Hall: 10.85m x 6.46m Gross Internal Floor Area: 76.2 m2 Services The property is serviced by electricity only. Mains water and sewer are conveniently located nearby. Grounds The property is situated on a small plot, with grounds surrounding the church bounded by wire fencing. Planning The Church Hall is not listed, and could be used, without the necessity of obtaining change of use consent, as a Creche, day nursery, day centre, educational establishment, museum or public library. It also has potential for a variety of other uses, such as retail, commercial or community uses, subject to obtaining the appropriate consents. Conversion to residential accommodation is also possible, again subject to the usual consents. Local Area Lionel is a village on the North of the Isle of Lewis and is less than a ten-minute drive from the Butt of Lewis. The village benefits from excellent access routes around the island and is only 26 miles from Stornoway. The neighbouring villages provide a wide range of amenities including shop, filling station, school, post office, bar restaurant, laundrette and charity shop. Stornoway is the main town of the Western Isles and the capital of Lewis. -

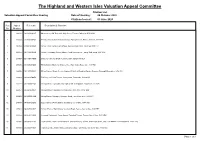

Appeal Citation List External

The Highland and Western Isles Valuation Appeal Committee Citation List Valuation Appeal Committee Hearing Date of Hearing : 06 October 2020 Citations Issued : 05 June 2020 Seq Appeal Reference Description & Situation No Number 1 269288 01/01/388013/7 Museum etc, Old Town Hall, High Street, Thurso, Caithness, KW14 8AJ 2 299360 01/05/010080/1 Primary School, Noss Primary School, Ackergill Street, Wick, Caithness, KW1 4DT 3 299359 01/05/585000/8 School, Wick Community Campus, Newton Road, Wick, Caithness, KW1 5LT 4 299358 02/11/027950/9 School, Secondary School, Manse Road, Kinlochbervie, Lairg, Sutherland, IV27 4RG 5 299357 02/13/081300/0 Distillery, Clynelish Distillery, Brora, Sutherland, KW9 6LR 6 259285 03/12/020600/4 Filling Station, Black Isle Motors, Tore, Muir of Ord, Ross-shire, IV6 7RZ 7 266056 03/21/009580/2 Filling Station, Skiach Service Station, 4D Airfield Road Ind Estate, Evanton, Dingwall, Ross-shire, IV16 9XJ 8 299363 03/23/335005/0 Distillery, Golf View Terrace, Invergordon, Ross-shire, IV18 0HW 9 259242 03/23/380240/5 Filling Station, Four Oaks, 130 High Street, Invergordon, Ross-shire, IV18 0AE 10 266057 03/32/465005/4 Filling Station, 1 Knockbreck Road, Tain, Ross-shire, IV19 1BW 11 266058 03/32/555164/0 Filling Station, Morangie, Morangie Road, Tain, Ross-shire, IV19 1PY 12 265484 04/05/032820/2 Supermarket & Filling Station, Broadford, Isle of Skye, IV49 9AB 13 299361 04/06/036250/2 School, Portree High School, Viewfield Road, Portree, Isle of Skye, IV51 9ET 14 299268 04/06/041450/8 Licensed Restaurant, Caroy House, -

Troutquest Guide to Trout Fishing on the Nc500

Version 1.2 anti-clockwise Roger Dowsett, TroutQuest www.troutquest.com Introduction If you are planning a North Coast 500 road trip and want to combine some fly fishing with sightseeing, you are in for a treat. The NC500 route passes over dozens of salmon rivers, and through some of the best wild brown trout fishing country in Europe. In general, the best trout fishing in the region will be found on lochs, as the feeding is generally richer there than in our rivers. Trout fishing on rivers is also less easy to find as most rivers are fished primarily for Atlantic salmon. Scope This guide is intended as an introduction to some of the main trout fishing areas that you may drive through or near, while touring on the NC500 route. For each of these areas, you will find links to further information, but please note, this is not a definitive list of all the trout fishing spots on the NC500. There is even more trout fishing available on the route than described here, particularly in the north and north-west, so if you see somewhere else ‘fishy’ on your trip, please enquire locally. Trout Fishing Areas on the North Coast 500 Route Page | 2 All Content ©TroutQuest 2017 Version 1.2 AC Licences, Permits & Methods The legal season for wild brown trout fishing in the UK runs from 15th March to 6th October, but most trout lochs and rivers in the Northern Highlands do not open until April, and in some cases the beginning of May. There is no close season for stocked rainbow trout fisheries which may be open earlier or later in the year. -

Fishing Permits Information

Fishing permit retailers in the National Park 1 River Fillan 7 Loch Daine Strathfillan Wigwams Angling Active, Stirling 01838 400251 01786 430400 www.anglingactive.co.uk 2 Loch Dochart James Bayne, Callander Portnellan Lodges 01877 330218 01838 300284 www.fishinginthetrossachs.co.uk www.portnellan.com Loch Dochart Estate 8 Loch Voil 01838 300315 Angling Active, Stirling www.lochdochart.co. uk 01786 430400 www.anglingactive.co.uk 3 Loch lubhair James Bayne, Callander Auchlyne & Suie Estate 01877 330218 01567 820487 Strathyre Village Shop www.auchlyne.co.uk 01877 384275 Loch Dochart Estate Angling Active, Stirling 01838 300315 01786 430400 www.lochdochart.co. uk www.anglingactive.co.uk News First, Killin 01567 820362 9 River Balvaig www.auchlyne.co.uk James Bayne, Callander Auchlyne & Suie Estate 01877 330218 01567 820487 www.fishinginthetrossachs.co.uk www.auchlyne.co.uk Forestry Commission, Aberfoyle 4 River Dochart 01877 382383 Aberfoyle Post Office Glen Dochart Caravan Park 01877 382231 01567 820637 Loch Dochart Estate 10 Loch Lubnaig 01838 300315 Forestry Commission, Aberfoyle www.lochdochart.co. uk 01877 382383 Suie Lodge Hotel Strathyre Village Shop 01567 820040 01877 384275 5 River Lochay 11 River Leny News First, Killin James Bayne, Callander 01567 820362 01877 330218 Drummond Estates www.fishinginthetrossachs.co.uk 01567 830400 Stirling Council Fisheries www.drummondtroutfarm.co.uk 01786 442932 6 Loch Earn 12 River Teith Lochearnhead Village Store Angling Active, Stirling 01567 830214 01786 430400 St.Fillans Village Store www.anglingactive.co.uk -

Archaeological Excavations at Castle Sween, Knapdale, Argyll & Bute, 1989-90

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, (1996)6 12 , 517-557 Archaeological excavation t Castlsa e Sween, Knapdale, Argyll & Bute, 1989-90 Gordon Ewart Triscottn Jo *& t with contributions by N M McQ Holmes, D Caldwell, H Stewart, F McCormick, T Holden & C Mills ABSTRACT Excavations Castleat Sween, Argyllin Bute,& have thrown castle of the history use lightthe on and from construction,s it presente 7200c th o t , day. forge A kilnsd evidencee an ar of industrial activity prior 1650.to Evidence rangesfor of buildings within courtyardthe amplifies previous descriptions castle. ofthe excavations The were funded Historicby Scotland (formerly SDD-HBM) alsowho supplied granta towards publicationthe costs. INTRODUCTION Castle Sween, a ruin in the care of Historic Scotland, stands on a low hill overlooking an inlet, Loch Sween, on the west side of Knapdale (NGR: NR 712 788, illus 1-3). Its history and architectural development have recently been reviewed thoroughl RCAHMe th y b y S (1992, 245-59) castle Th . e s theri e demonstrate havo dt e five major building phases datin c 1200 o earle gt th , y 13th century, c 1300 15te th ,h century 16th-17te th d an , h centur core y (illueTh . wor 120c 3) s f ko 0 consista f so small quadrilateral enclosure castle. A rectangular wing was added to its west face in the early 13th century. This win s rebuilgwa t abou t circulaa 1300 d an , r tower with latrinee grounth n o sd floor north-ease th o buils t n wa o t t enclosurcornee th 15te f o rth hn i ecentury l thesAl . -

North Highlands North Highlands

Squam Lakes Natural Science Center’s North Highlands Wester Ross, Sutherland, Caithness and Easter Ross June 14-27, 2019 Led by Iain MacLeod 2019 Itinerary Join native Scot Iain MacLeod for a very personal, small-group tour of Scotland’s Northern Highlands. We will focus on the regions known as Wester Ross, Sutherland, Caithness and Easter Ross. The hotels are chosen by Iain for their comfort, ambiance, hospitality, and excellent food. Iain personally arranges every detail—flights, meals, transportation and daily destinations. Note: This is a brand new itinerary, so we will be exploring this area together. June 14: Fly from Logan Airport, Boston to Scotland. I hope that we will be able to fly directly into Inverness and begin our trip from there. Whether we fly through London, Glasgow or Dublin will be determined later in 2018. June 15: Arrive in Inverness. We will load up the van and head west towards the spectacular west coast passing by Lochluichart, Achnasheen and Kinlochewe along the way. We will arrive in the late afternoon at the Sheildaig Lodge Hotel (http://www.shieldaiglodge.com/) which will be our base for four nights. June 16-18: We will explore Wester Ross. Highlights will include Beinn Eighe National Nature Reserve, Inverewe Gardens, Loch Torridon and the Torridon Countryside Center. We’ll also take a boat trip out to the Summer Isles on Shearwater Summer Isle Cruises out of Ullapool. We’ll have several opportunities to see White-tailed Eagles, Golden Eagles, Black-throated Divers as well as Otters and Seals. June 19: We’ll head north along the west coast of Wester Ross and Sutherland past Loch Assynt and Ardvreck Castle, all the way up tp the north coast. -

11A Upper Bayble, Point, Isle of Lewis, HS2 0QH Offers Around £73,000 Are Invited

11a Upper Bayble, Point, HR Isle of Lewis, HS2 0QH Offers around £73,000 are invited Detached 1 bedroom cottage is offered for sale In a popular and peaceful location Interrupted seaward aspect to the front Property retaining and preserving common characteristics Kitchen and living area Front aspect double bedroom Bathroom with bath/shower mixer taps Dual aspect front porch Hall vestibule Windows are of double glazed UPVC design Exterior door is of timber construction Heating is by way of electrically fired storage units and panels Hot water is via an unvented pressurised cylinder Enclosed garden with established hedgerow Private off road driveway and 2 garden sheds Within easy access to all local and town amenities EPC Banding - E 77 Cromwell Street ∙ Stornoway ∙ Isle of Lewis ∙ HS1 2DG Tel: 01851 704 003 Fax: 01851 704 473 Email: [email protected] Website: western-isles-property.co.uk Kitchen and Living Area Kitchen and Living Area Front Porch Bedroom Bedroom Bathroom Directions Accommodation Travel out of Stornoway on the A866 towards Point. Continue on the main Kitchen and Living Area: 3.56m x 3.40m road until you arrive in Garrabost. Take the first right hand turn sign posted for Dual aspect double glazed UPVC windows. Fitted wall and floor units with Pabail Uarach passing the new Bayble school on your left. Then take the first integrated stainless steel sink, tall fridge freezer, 4 ring hob and oven. Plumbed left hand turn for Pabail Uarach and continue until the T junction. Take a left for washing machine. Tiled to splashback. -

The Arms of the Baronial and Police Burghs of Scotland

'^m^ ^k: UC-NRLF nil! |il!|l|ll|ll|l||il|l|l|||||i!|||!| C E 525 bm ^M^ "^ A \ THE ARMS OF THE BARONIAL AND POLICE BURGHS OF SCOTLAND Of this Volume THREE HUNDRED AND Fifteen Copies have been printed, of which One Hundred and twenty are offered for sale. THE ARMS OF THE BARONIAL AND POLICE BURGHS OF SCOTLAND BY JOHN MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T. H. J. STEVENSON AND H. W. LONSDALE EDINBURGH WILLIAM BLACKWOOD & SONS 1903 UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME. THE ARMS OF THE ROYAL AND PARLIAMENTARY BURGHS OF SCOTLAND. BY JOHN, MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T., J. R. N. MACPHAIL, AND H. W. LONSDALE. With 131 Engravings on Wood and 11 other Illustrations. Crown 4to, 2 Guineas net. ABERCHIRDER. Argent, a cross patee gules. The burgh seal leaves no doubt of the tinctures — the field being plain, and the cross scored to indicate gules. One of the points of difference between the bearings of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs on the one hand and those of the I Police Burghs on the other lies in the fact that the former carry castles and ships to an extent which becomes almost monotonous, while among the latter these bearings are rare. On the other hand, the Police Burghs very frequently assume a charge of which A 079 2 Aberchirder. examples, in the blazonry of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs, are very rare : this is the cross, derived apparently from the fact that their market-crosses are the most prominent of their ancient monuments. In cases where the cross calvary does not appear, a cross of some other kind is often found, as in the present instance. -

Site Selection Document: Summary of the Scientific Case for Site Selection

West Coast of the Outer Hebrides Proposed Special Protection Area (pSPA) No. UK9020319 SPA Site Selection Document: Summary of the scientific case for site selection Document version control Version and Amendments made and author Issued to date and date Version 1 Formal advice submitted to Marine Scotland on Marine draft SPA. Scotland Nigel Buxton & Greg Mudge 10/07/14 Version 2 Updated to reflect change in site status from draft Marine to proposed in preparation for possible formal Scotland consultation. 30/06/15 Shona Glen, Tim Walsh & Emma Philip Version 3 Updated with minor amendments to address Marine comments from Marine Scotland Science in Scotland preparation for the SPA stakeholder workshop. 23/02/16 Emma Philip Version 4 Revised format, using West Coast of Outer MPA Hebrides as a template, to address comments Project received at the SPA stakeholder workshop. Steering Emma Philip Group 07/04/16 Version 5 Text updated to reflect proposed level of detail for Marine final versions. Scotland Emma Philip 18/04/16 Version 6 Document updated to address requirements of Greg revised format agreed by Marine Scotland. Mudge Glen Tyler & Emma Philip 19/06/16 Version 7 Quality assured Emma Greg Mudge Philip 20/6/16 Version 8 Final draft for approval Andrew Emma Philip Bachell 22/06/16 Version 9 Final version for submission to Marine Scotland Marine Scotland 24/06/16 Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 2. Site summary ..................................................................................................... 2 3. Bird survey information .................................................................................... 5 4. Assessment against the UK SPA Selection Guidelines ................................. 7 5. Site status and boundary ................................................................................ 13 6. Information on qualifying species ................................................................. -

Chris Ryan on Behalf of 52 Lewis and Harris Businesses – 3 April 2008

Submission from Chris Ryan on behalf of 52 Lewis and Harris businesses – 3 April 2008 Dear Sir/Madam 7-DAY FERRY SERVICES TO LEWIS & HARRIS The undersigned businesses, all based in the Western Isles, request that Sunday ferry services to Lewis & Harris should be introduced in the summer of 2008. This will be a necessary and long overdue development with the potential to improve the islands’ tourism industry in line with the Scottish Governments’ target of a 50% increase in tourism revenues. The proposed introduction of RET fares from October 2008 is also likely to result in increased demand and additional capacity will be needed to cope with peak season demand, particularly at weekends. However, our view as businesses is that Sunday services must be phased-in ahead of RET and that they should certainly be in place for summer 2008. Apart from the immediate boost for the local economy, this would give accommodation providers and tourism related businesses an indication of the response to weekend services and allow for business planning for the summer of 2009, which is the Year of Homecoming. Quite apart from the many social benefits, Sunday ferry services will make a major difference to the local economy by extending the tourist season, enabling businesses to work more efficiently and spreading visitor benefits throughout the islands. As a specific example, the Hebridean Celtic Festival, held in July, attracts over 15,000 people and contributes over £1m to the local economy. A Sunday ferry service would mean that many visitors to the festival would stay an extra night, enjoy all 4 –days of the festival and see more of the islands. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland.