Archaeological Excavations at Castle Sween, Knapdale, Argyll & Bute, 1989-90

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Safap October2016 Minutes Final

Minutes of the meeting of THE SCOTTISH ARCHAEOLOGICAL FINDS ALLOCATION PANEL 10:45am, Thursday 27th October 2016 Present: Dr Evelyn Silber (Chair), Neil Curtis, Dr Murray Cook (via Skype), Jilly Burns (NMS), Paul MacDonald, Richard Welander (HES), Mary McLeod Rivett In attendance: Stuart Campbell (TTU), Dr Natasha Ferguson (TTU), Andrew Brown (QLTR Solicitor). Dr Natasha Ferguson took the minutes 1. Apologies Apologies from Jacob O’Sullivan (MGS). 2. Chair Remarks The Chair informed the panel that the QLTR had received a response from SG to a letter highlighting issues relating to increasing numbers of disclaimed cases. It was agreed the points would be discussed further at the Annual Review Meeting on 14th November. The panel agreed to form a sub-committee (of NC, JB, RW & AB) to deal with revisions of the Code of Practice in relation to multiple applications. The next date of the panel meeting confirmed as Thursday 23rd March 2017. Further dates in 2017 to be proposed. It is proposed that the number of meetings is reduced to three by combining the Annual Review meeting with a panel meeting. This will be discussed at the next Annual Review meeting on 14th November 2016. 3. Discussion of Galloway Hoard, valuations and timescales JB (NMS) was absent from this discussion. The panel were updated on the current status of the Galloway Hoard, including projected timescales for allocation. The panel also discussed the criteria for assessing the valuations. The 31st January 2017 was agreed as a proposed date to hold an extraordinary SAFAP meeting in relation to allocating the Galloway Hoard. -

Scottish Borders Newsletter Autumn 2017

Borders Newsletter Issue 19 Autumn 2017 http://eastscotland-butterflies.org.uk/ https://www.facebook.com/EastScotlandButterflyConservation Welcome to the latest issue of our What's the Difference between a Butterfly and a Moth? newsletter for Butterfly Conservation members and many other people When Barbara and I ran a stand at the St Abbs Science Day in August every one of living in the Scottish Borders and the fifty or more people we talked to asked us this question - yes, they really all did! further afield. Please forward it to Fortunately we were armed with both a few technical answers as well as a nice little others who have an interest in quiz to see if people could tell the difference - this was a set of about 30 pictures of butterflies & moths and who might both butterflies and moths along with a few wild cards of other things that looked a like to read it and be kept in touch bit like a moth. The great thing about the quiz is that it suits all ages and all levels of with our activities. knowledge - only one person got them all right and it led on to many interesting Barry Prater discussions. [email protected] Tel 018907 52037 Contents Highlights from this year ........Barry Prater A White Letter Day ................... Iain Cowe The Comfrey Ermel, a Moth new to Scotland ................................... Nick Cook Large Red-belted Clearwings in Berwickshire .......................... David Long Another very popular way of engaging with youngsters is the reveal of moth trap Plant Communities for Butterflies & Moths: contents and Philip Hutton has been working with the SWT Wildlife Watch group in Part 7, Oakwoods contd. -

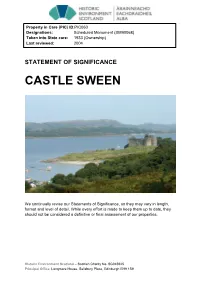

Castle Sween Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID:PIC060 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90068) Taken into State care: 1933 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2004 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE CASTLE SWEEN We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2018 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH CASTLE SWEEN BRIEF DESCRIPTION Castle Sween is thought to be the earliest surviving stone castle on the Scottish Mainland. It sits on a low rocky ridge on the east shore of Loch Sween with a commanding prospect over Loch Sween and out to Jura. -

Fishing Permits Information

Fishing permit retailers in the National Park 1 River Fillan 7 Loch Daine Strathfillan Wigwams Angling Active, Stirling 01838 400251 01786 430400 www.anglingactive.co.uk 2 Loch Dochart James Bayne, Callander Portnellan Lodges 01877 330218 01838 300284 www.fishinginthetrossachs.co.uk www.portnellan.com Loch Dochart Estate 8 Loch Voil 01838 300315 Angling Active, Stirling www.lochdochart.co. uk 01786 430400 www.anglingactive.co.uk 3 Loch lubhair James Bayne, Callander Auchlyne & Suie Estate 01877 330218 01567 820487 Strathyre Village Shop www.auchlyne.co.uk 01877 384275 Loch Dochart Estate Angling Active, Stirling 01838 300315 01786 430400 www.lochdochart.co. uk www.anglingactive.co.uk News First, Killin 01567 820362 9 River Balvaig www.auchlyne.co.uk James Bayne, Callander Auchlyne & Suie Estate 01877 330218 01567 820487 www.fishinginthetrossachs.co.uk www.auchlyne.co.uk Forestry Commission, Aberfoyle 4 River Dochart 01877 382383 Aberfoyle Post Office Glen Dochart Caravan Park 01877 382231 01567 820637 Loch Dochart Estate 10 Loch Lubnaig 01838 300315 Forestry Commission, Aberfoyle www.lochdochart.co. uk 01877 382383 Suie Lodge Hotel Strathyre Village Shop 01567 820040 01877 384275 5 River Lochay 11 River Leny News First, Killin James Bayne, Callander 01567 820362 01877 330218 Drummond Estates www.fishinginthetrossachs.co.uk 01567 830400 Stirling Council Fisheries www.drummondtroutfarm.co.uk 01786 442932 6 Loch Earn 12 River Teith Lochearnhead Village Store Angling Active, Stirling 01567 830214 01786 430400 St.Fillans Village Store www.anglingactive.co.uk -

Camping Pocket Guide

CONTENTS Get Ready for Camping 04 Add To Your Experience 07 Enjoy Family Picnics 08 Scenic Scotland 10 Visit National Parks 14 Amazing Wildlife 16 GET READY FOR CAMPING - Stargazing - Experience the freedom of a touring trip, where you can Sleeping under the stars is the perfect opportunity to wake up in a different part of the country every day. Or get familiar with the wonders of the sky at night. Plan enjoy a bit of luxury at a holiday park and spend a restful a camping trip to the Glentrool Camping and Caravan week in the comfy surrounds of a state-of-the-art static Site in the Galloway Forest Park, the UK’s first Dark Sky caravan, or pack in some fun activities with the kids. Park, or sail to Scotland’s first Dark Sky island. There’s There’s a camping and caravanning holiday in Scotland minimum light pollution on the Isle of Coll, where the to suit every preference and budget. nearest lamppost is 20 miles away! Start planning a break today and find your perfect Experience more stargazing opportunities and discover camping or caravanning destination. Scotland’s inky black skies on our website. - Stunning views - - Campsites near castles - Summer is the time to be spontaneous – pack the tent Why not combine your camping or caravanning trip into the car, head out onto the open road, and pitch up in with a bit of history and book a pitch in the grounds of a some beautiful locations. You’ll find campsites set below castle? You’ll find such camping grounds in many parts breathtaking mountain ranges, overlooking pristine of the country, from the impressive 18th century Culzean beaches, or in the middle of lush, open countryside. -

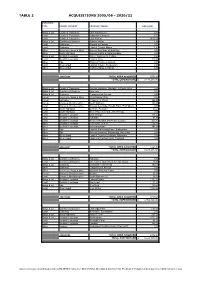

Table 2-Acquisitions (Web Version).Xlsx TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21

TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21 PURCHASE TYPE FOREST DISTRICT PROPERTY NAME AREA (HA) Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Edra Farmhouse 2.30 Land Cowal & Trossachs Ardgartan Campsite 6.75 Land Cowal & Trossachs Loch Katrine 9613.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders Jufrake House 4.86 Land Galloway Ground at Corwar 0.70 Land Galloway Land at Corwar Mains 2.49 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye Access Servitude at Boblainy 0.00 Other North Highland Access Rights at Strathrusdale 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Scottish Lowlands 3 Keir, Gardener's Cottage 0.26 Land Scottish Lowlands Land at Croy 122.00 Other Tay Rannoch School, Kinloch 0.00 Land West Argyll Land at Killean, By Inverary 0.00 Other West Argyll Visibility Splay at Killean 0.00 2005/2006 TOTAL AREA ACQUIRED 9752.36 TOTAL EXPENDITURE £ 3,143,260.00 Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Access Variation, Ormidale & South Otter 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders 4 Eshiels 0.18 Bldgs & Ld Galloway Craigencolon Access 0.00 Forest Inverness, Ross & Skye 1 Highlander Way 0.27 Forest Lochaber Chapman's Wood 164.60 Forest Moray & Aberdeenshire South Balnoon 130.00 Land Moray & Aberdeenshire Access Servitude, Raefin Farm, Fochabers 0.00 Land North Highland Auchow, Rumster 16.23 Land North Highland Water Pipe Servitude, No 9 Borgie 0.00 Land Scottish Lowlands East Grange 216.42 Land Scottish Lowlands Tulliallan 81.00 Land Scottish Lowlands Wester Mosshat (Horberry) (Lease) 101.17 Other Scottish Lowlands Cochnohill (1 & 2) 556.31 Other Scottish Lowlands Knockmountain 197.00 Other Tay Land at Blackcraig Farm, Blairgowrie -

The Arms of the Baronial and Police Burghs of Scotland

'^m^ ^k: UC-NRLF nil! |il!|l|ll|ll|l||il|l|l|||||i!|||!| C E 525 bm ^M^ "^ A \ THE ARMS OF THE BARONIAL AND POLICE BURGHS OF SCOTLAND Of this Volume THREE HUNDRED AND Fifteen Copies have been printed, of which One Hundred and twenty are offered for sale. THE ARMS OF THE BARONIAL AND POLICE BURGHS OF SCOTLAND BY JOHN MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T. H. J. STEVENSON AND H. W. LONSDALE EDINBURGH WILLIAM BLACKWOOD & SONS 1903 UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME. THE ARMS OF THE ROYAL AND PARLIAMENTARY BURGHS OF SCOTLAND. BY JOHN, MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T., J. R. N. MACPHAIL, AND H. W. LONSDALE. With 131 Engravings on Wood and 11 other Illustrations. Crown 4to, 2 Guineas net. ABERCHIRDER. Argent, a cross patee gules. The burgh seal leaves no doubt of the tinctures — the field being plain, and the cross scored to indicate gules. One of the points of difference between the bearings of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs on the one hand and those of the I Police Burghs on the other lies in the fact that the former carry castles and ships to an extent which becomes almost monotonous, while among the latter these bearings are rare. On the other hand, the Police Burghs very frequently assume a charge of which A 079 2 Aberchirder. examples, in the blazonry of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs, are very rare : this is the cross, derived apparently from the fact that their market-crosses are the most prominent of their ancient monuments. In cases where the cross calvary does not appear, a cross of some other kind is often found, as in the present instance. -

Argyll Bird Report with Sstematic List for the Year

ARGYLL BIRD REPORT with Systematic List for the year 1998 Volume 15 (1999) PUBLISHED BY THE ARGYLL BIRD CLUB Cover picture: Barnacle Geese by Margaret Staley The Fifteenth ARGYLL BIRD REPORT with Systematic List for the year 1998 Edited by J.C.A. Craik Assisted by P.C. Daw Systematic List by P.C. Daw Published by the Argyll Bird Club (Scottish Charity Number SC008782) October 1999 Copyright: Argyll Bird Club Printed by Printworks Oban - ABOUT THE ARGYLL BIRD CLUB The Argyll Bird Club was formed in 19x5. Its main purpose is to play an active part in the promotion of ornithology in Argyll. It is recognised by the Inland Revenue as a charity in Scotland. The Club holds two one-day meetings each year, in spring and autumn. The venue of the spring meeting is rotated between different towns, including Dunoon, Oban. LochgilpheadandTarbert.Thc autumn meeting and AGM are usually held in Invenny or another conveniently central location. The Club organises field trips for members. It also publishes the annual Argyll Bird Report and a quarterly members’ newsletter, The Eider, which includes details of club activities, reports from meetings and field trips, and feature articles by members and others, Each year the subscription entitles you to the ArgyZl Bird Report, four issues of The Eider, and free admission to the two annual meetings. There are four kinds of membership: current rates (at 1 October 1999) are: Ordinary E10; Junior (under 17) E3; Family €15; Corporate E25 Subscriptions (by cheque or standing order) are due on 1 January. Anyonejoining after 1 Octoberis covered until the end of the following year. -

History of the Lands and Their Owners in Galloway

H.E NTIL , 4 Pfiffifinfi:-fit,mnuuugm‘é’r§ms, ».IVI\ ‘!{5_&mM;PAmnsox, _ V‘ V itbmnvncn. if,‘4ff V, f fixmmum ‘xnmonasfimwini cAa'1'm-no17t§1[.As'. xmgompnxenm. ,7’°':",*"-‘V"'{";‘.' ‘9“"3iLfA31Dan1r,_§v , qyuwgm." “,‘,« . ERRATA. Page 1, seventeenth line. For “jzim—g1'é.r,”read "j2'1r11—gr:ir." 16. Skaar, “had sasiik of the lands of Barskeoch, Skar,” has been twice erroneously printed. 19. Clouden, etc., page 4. For “ land of,” read “lands of.” 24. ,, For “ Lochenket," read “ Lochenkit.” 29.,9 For “ bo,” read “ b6." 48, seventh line. For “fill gici de gord1‘u1,”read“fill Riei de gordfin.” ,, nineteenth line. For “ Sr,” read “ Sr." 51 I ) 9 5’ For “fosse,” read “ fossé.” 63, sixteenth line. For “ your Lords,” read “ your Lord’s.” 143, first line. For “ godly,” etc., read “ Godly,” etc. 147, third line. For “ George Granville, Leveson Gower," read without the comma.after Granville. 150, ninth line. For “ Manor,” read “ Mona.” 155,fourth line at foot. For “ John Crak,” read “John Crai ." 157, twenty—seventhline. For “Ar-byll,” read “ Ar by1led.” 164, first line. For “ Galloway,” read “ Galtway.” ,, second line. For “ Galtway," read “ Galloway." 165, tenth line. For “ King Alpine," read “ King Alpin." ,, seventeenth line. For “ fosse,” read “ fossé.” 178, eleventh line. For “ Berwick,” read “ Berwickshire.” 200, tenth line. For “ Murmor,” read “ murinor.” 222, fifth line from foot. For “Alfred-Peter,” etc., read “Alfred Peter." 223 .Ba.rclosh Tower. The engraver has introduced two figures Of his own imagination, and not in our sketch. 230, fifth line from foot. For “ his douchter, four,” read “ his douchter four.” 248, tenth line. -

Sub-Regional Forest Planning Themes

August 2009 A project for Forestry Commission Scotland (FCS) Evaluation of the Land Use Strategy (LUS) Forestry Focussed Sub- Regional Pilot Studies Final Report 27th March 2015 Collingwood Environmental Planning Limited Final Report March 2015 Project title: Evaluation of the Land Use Strategy (LUS) Forestry Focussed Sub-Regional Pilot Studies Contracting organisation: Forestry Commission Scotland (FCS) Contractor: Collingwood Environmental Planning Limited (CEP) Lead details: Head office: Address: 1E The Chandlery, 50 Westminster Bridge Road, London, SE1 7QY Contact: Ric Eales (Project Director) Tel. 020 7407 8700 Fax. 020 7928 6950 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cep.co.uk Scottish office: Address: c/o Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Strathclyde, Level 5, James Weir Building, 75 Montrose Street, Glasgow G1 1XJ Contact: Dr Peter Phillips (Project Manager) Tel. 0141 416 8700 Email: [email protected] Report details: Report title: Final Report Date issued: 27th March 2015 Version no.: 2 Author(s): Dr Peter Phillips, Paula Orr and Rolands Sadauskis Reviewed by: Ric Eales Evaluation of the LUS Forestry Focussed Collingwood Environmental Planning Sub-Regional Pilot Studies 1 Final Report March 2015 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................. 3 1.1 Objectives of the evaluation ........................................................................................................................ 3 1.2 Purpose and contents of -

The Isle of Lewis & Harris (Chaps. VII & VIII)

THE ISLE OF LEWIS AND HARRIS CHAPTER I A STUDY IN ENVIRONMENT AND LANDSCAPE BRITISH COMMUNITY (A) THE GEOGRAPHIC SETTING: THE BRITISH ISLES, SCOTLAND AND THE by HIGHLANDS AND ISLES ARTHUR GEDDES i. A 'Heart' of the 'North and West' of Britain The Isle of Lewis and Harris (1955) by Arthur Geddes, the son N the ' Outer' Hebrides, commonly regarded as the of the great planner and pioneering human ecologist Patrick Geddes, is long out of print from EUP and hard to procure. most ' outlying ' inhabited lands of the British Isles, Chapters VII and VIII on the spiritual and religious life of the I are revealed not only the most ancient of British rocks, community remain of very great importance, and this PDF of the Archaean, but probably the oldest form of communal them has been produced for my students' use and not for any life in Britain. This life, in present and past, will interest commercial purpose. Also, below is Geddes' remarkable map of the Hebrides from p. 3, and at the back the contents pages. Alastair Mclntosh, Honorary Fellow, University of Edinburgh. EDINBURGH AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS *955 FIG. I.—Global view of the ' Outer' Hebrides, seen as the heart of the ' North and West' of Britain. 3 CH. VII SPIRITUAL LIFE OF COMMUNITY xviii. 19-20). The worldly wise might think that the spiritual fare of these poor folk must have been lean indeed ; while others, having heard much of the Highlanders' ' pagan ' superstitions, may think even worse ! The evi CHAPTER VII dence from which to judge is found in survivals from a rich lore, and for most readers seen but ' darkly' through THE SPIRITUAL LIFE OF THE prose translations from the poetry of a tongue now known COMMUNITY to few. -

Scotland Information for S1376

European Community Directive on the Conservation of Natural Habitats and of Wild Fauna and Flora (92/43/EEC) Fourth Report by the United Kingdom under Article 17 on the implementation of the Directive from January 2013 to December 2018 Supporting documentation for the conservation status assessment for the species: S1376 ‐ Maerl (Lithothamnium corallioides) SCOTLAND IMPORTANT NOTE ‐ PLEASE READ • The information in this document is a country‐level contribution to the UK Reporton the conservation status of this species, submitted to the European Commission aspart of the 2019 UK Reporting under Article 17 of the EU Habitats Directive. • The 2019 Article 17 UK Approach document provides details on how this supporting information was used to produce the UK Report. • The UK Report on the conservation status of this species is provided in a separate doc‐ ument. • The reporting fields and options used are aligned to those set out in the European Com‐ mission guidance. • Explanatory notes (where provided) by the country are included at the end. These pro‐ vide an audit trail of relevant supporting information. • Some of the reporting fields have been left blank because either: (i) there was insuffi‐ cient information to complete the field; (ii) completion of the field was not obligatory; (iii) the field was not relevant to this species (section 12 Natura 2000 coverage forAnnex II species) and/or (iv) the field was only relevant at UK‐level (sections 9 Future prospects and 10 Conclusions). • For technical reasons, the country‐level future trends for Range, Population and Habitat for the species are only available in a separate spreadsheet that contains all the country‐ level supporting information.