Sub-Regional Forest Planning Themes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Safap October2016 Minutes Final

Minutes of the meeting of THE SCOTTISH ARCHAEOLOGICAL FINDS ALLOCATION PANEL 10:45am, Thursday 27th October 2016 Present: Dr Evelyn Silber (Chair), Neil Curtis, Dr Murray Cook (via Skype), Jilly Burns (NMS), Paul MacDonald, Richard Welander (HES), Mary McLeod Rivett In attendance: Stuart Campbell (TTU), Dr Natasha Ferguson (TTU), Andrew Brown (QLTR Solicitor). Dr Natasha Ferguson took the minutes 1. Apologies Apologies from Jacob O’Sullivan (MGS). 2. Chair Remarks The Chair informed the panel that the QLTR had received a response from SG to a letter highlighting issues relating to increasing numbers of disclaimed cases. It was agreed the points would be discussed further at the Annual Review Meeting on 14th November. The panel agreed to form a sub-committee (of NC, JB, RW & AB) to deal with revisions of the Code of Practice in relation to multiple applications. The next date of the panel meeting confirmed as Thursday 23rd March 2017. Further dates in 2017 to be proposed. It is proposed that the number of meetings is reduced to three by combining the Annual Review meeting with a panel meeting. This will be discussed at the next Annual Review meeting on 14th November 2016. 3. Discussion of Galloway Hoard, valuations and timescales JB (NMS) was absent from this discussion. The panel were updated on the current status of the Galloway Hoard, including projected timescales for allocation. The panel also discussed the criteria for assessing the valuations. The 31st January 2017 was agreed as a proposed date to hold an extraordinary SAFAP meeting in relation to allocating the Galloway Hoard. -

Camping Pocket Guide

CONTENTS Get Ready for Camping 04 Add To Your Experience 07 Enjoy Family Picnics 08 Scenic Scotland 10 Visit National Parks 14 Amazing Wildlife 16 GET READY FOR CAMPING - Stargazing - Experience the freedom of a touring trip, where you can Sleeping under the stars is the perfect opportunity to wake up in a different part of the country every day. Or get familiar with the wonders of the sky at night. Plan enjoy a bit of luxury at a holiday park and spend a restful a camping trip to the Glentrool Camping and Caravan week in the comfy surrounds of a state-of-the-art static Site in the Galloway Forest Park, the UK’s first Dark Sky caravan, or pack in some fun activities with the kids. Park, or sail to Scotland’s first Dark Sky island. There’s There’s a camping and caravanning holiday in Scotland minimum light pollution on the Isle of Coll, where the to suit every preference and budget. nearest lamppost is 20 miles away! Start planning a break today and find your perfect Experience more stargazing opportunities and discover camping or caravanning destination. Scotland’s inky black skies on our website. - Stunning views - - Campsites near castles - Summer is the time to be spontaneous – pack the tent Why not combine your camping or caravanning trip into the car, head out onto the open road, and pitch up in with a bit of history and book a pitch in the grounds of a some beautiful locations. You’ll find campsites set below castle? You’ll find such camping grounds in many parts breathtaking mountain ranges, overlooking pristine of the country, from the impressive 18th century Culzean beaches, or in the middle of lush, open countryside. -

Archaeological Excavations at Castle Sween, Knapdale, Argyll & Bute, 1989-90

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, (1996)6 12 , 517-557 Archaeological excavation t Castlsa e Sween, Knapdale, Argyll & Bute, 1989-90 Gordon Ewart Triscottn Jo *& t with contributions by N M McQ Holmes, D Caldwell, H Stewart, F McCormick, T Holden & C Mills ABSTRACT Excavations Castleat Sween, Argyllin Bute,& have thrown castle of the history use lightthe on and from construction,s it presente 7200c th o t , day. forge A kilnsd evidencee an ar of industrial activity prior 1650.to Evidence rangesfor of buildings within courtyardthe amplifies previous descriptions castle. ofthe excavations The were funded Historicby Scotland (formerly SDD-HBM) alsowho supplied granta towards publicationthe costs. INTRODUCTION Castle Sween, a ruin in the care of Historic Scotland, stands on a low hill overlooking an inlet, Loch Sween, on the west side of Knapdale (NGR: NR 712 788, illus 1-3). Its history and architectural development have recently been reviewed thoroughl RCAHMe th y b y S (1992, 245-59) castle Th . e s theri e demonstrate havo dt e five major building phases datin c 1200 o earle gt th , y 13th century, c 1300 15te th ,h century 16th-17te th d an , h centur core y (illueTh . wor 120c 3) s f ko 0 consista f so small quadrilateral enclosure castle. A rectangular wing was added to its west face in the early 13th century. This win s rebuilgwa t abou t circulaa 1300 d an , r tower with latrinee grounth n o sd floor north-ease th o buils t n wa o t t enclosurcornee th 15te f o rth hn i ecentury l thesAl . -

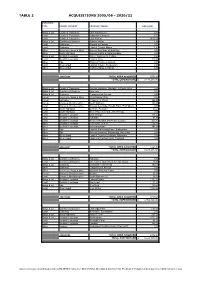

Table 2-Acquisitions (Web Version).Xlsx TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21

TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21 PURCHASE TYPE FOREST DISTRICT PROPERTY NAME AREA (HA) Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Edra Farmhouse 2.30 Land Cowal & Trossachs Ardgartan Campsite 6.75 Land Cowal & Trossachs Loch Katrine 9613.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders Jufrake House 4.86 Land Galloway Ground at Corwar 0.70 Land Galloway Land at Corwar Mains 2.49 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye Access Servitude at Boblainy 0.00 Other North Highland Access Rights at Strathrusdale 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Scottish Lowlands 3 Keir, Gardener's Cottage 0.26 Land Scottish Lowlands Land at Croy 122.00 Other Tay Rannoch School, Kinloch 0.00 Land West Argyll Land at Killean, By Inverary 0.00 Other West Argyll Visibility Splay at Killean 0.00 2005/2006 TOTAL AREA ACQUIRED 9752.36 TOTAL EXPENDITURE £ 3,143,260.00 Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Access Variation, Ormidale & South Otter 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders 4 Eshiels 0.18 Bldgs & Ld Galloway Craigencolon Access 0.00 Forest Inverness, Ross & Skye 1 Highlander Way 0.27 Forest Lochaber Chapman's Wood 164.60 Forest Moray & Aberdeenshire South Balnoon 130.00 Land Moray & Aberdeenshire Access Servitude, Raefin Farm, Fochabers 0.00 Land North Highland Auchow, Rumster 16.23 Land North Highland Water Pipe Servitude, No 9 Borgie 0.00 Land Scottish Lowlands East Grange 216.42 Land Scottish Lowlands Tulliallan 81.00 Land Scottish Lowlands Wester Mosshat (Horberry) (Lease) 101.17 Other Scottish Lowlands Cochnohill (1 & 2) 556.31 Other Scottish Lowlands Knockmountain 197.00 Other Tay Land at Blackcraig Farm, Blairgowrie -

History of the Lands and Their Owners in Galloway

H.E NTIL , 4 Pfiffifinfi:-fit,mnuuugm‘é’r§ms, ».IVI\ ‘!{5_&mM;PAmnsox, _ V‘ V itbmnvncn. if,‘4ff V, f fixmmum ‘xnmonasfimwini cAa'1'm-no17t§1[.As'. xmgompnxenm. ,7’°':",*"-‘V"'{";‘.' ‘9“"3iLfA31Dan1r,_§v , qyuwgm." “,‘,« . ERRATA. Page 1, seventeenth line. For “jzim—g1'é.r,”read "j2'1r11—gr:ir." 16. Skaar, “had sasiik of the lands of Barskeoch, Skar,” has been twice erroneously printed. 19. Clouden, etc., page 4. For “ land of,” read “lands of.” 24. ,, For “ Lochenket," read “ Lochenkit.” 29.,9 For “ bo,” read “ b6." 48, seventh line. For “fill gici de gord1‘u1,”read“fill Riei de gordfin.” ,, nineteenth line. For “ Sr,” read “ Sr." 51 I ) 9 5’ For “fosse,” read “ fossé.” 63, sixteenth line. For “ your Lords,” read “ your Lord’s.” 143, first line. For “ godly,” etc., read “ Godly,” etc. 147, third line. For “ George Granville, Leveson Gower," read without the comma.after Granville. 150, ninth line. For “ Manor,” read “ Mona.” 155,fourth line at foot. For “ John Crak,” read “John Crai ." 157, twenty—seventhline. For “Ar-byll,” read “ Ar by1led.” 164, first line. For “ Galloway,” read “ Galtway.” ,, second line. For “ Galtway," read “ Galloway." 165, tenth line. For “ King Alpine," read “ King Alpin." ,, seventeenth line. For “ fosse,” read “ fossé.” 178, eleventh line. For “ Berwick,” read “ Berwickshire.” 200, tenth line. For “ Murmor,” read “ murinor.” 222, fifth line from foot. For “Alfred-Peter,” etc., read “Alfred Peter." 223 .Ba.rclosh Tower. The engraver has introduced two figures Of his own imagination, and not in our sketch. 230, fifth line from foot. For “ his douchter, four,” read “ his douchter four.” 248, tenth line. -

6335 Rhins of Galloway Lighthouse Booklet 200X110

Lighthouse Guide Discover the aids to navigation on the Rhins of Galloway Coast Path Since people first ventured out on perilous journeys across the sea many attempts have been made to build landmarks warning sailors of dangers or guiding them to safety. This guide will help you discover lighthouses, foghorns and beacons along the Rhins of Galloway Coast Path as well as reveal some of the ships that have been wrecked on the rugged shore. This Lighthouse Guide has been produced as part of the Rhins of Galloway Coast Path project managed by Dumfries and Galloway Council. Portpatrick Cover: Corsewall Lighthouse How to use this guide The 3 operational Lighthouses on the Rhins are important features on the coastal landscape, managed by the Northern Lighthouse Board to perform a vital role in keeping mariners safe in all weathers. Discover a variety of navigational aids many of which are designated as listed buildings. Get up close with lighthouse tours and an exhibition at the Mull of Galloway Lighthouse or admire at a distance decommissioned lighthouses and redundant beacons. The map at the back of the guide shows you the location of these visually striking reminders of how dangerous the rocky coast of the Rhins can be to mariners. Killantringan Lighthouse Mull of Galloway Lighthouse Designed by Robert Stevenson and first lit in 1830, the Mull of Galloway Lighthouse is perched on Scotland’s most southerly point. It was automated in 1987 and the former Lightkeepers’ accommodation are now managed as self-catering holiday 1 cottages. Structure: White tower 26m high Position:54°38.1’N 4°51.4’W Character:Flashing white once every 20 seconds Nominal range:22 miles Lighthouse Tours, Exhibition & Foghorn The Mull of Galloway Lighthouse is open to visitors during the summer with the exhibition open every day and tours available at weekends and daily in July and August. -

Scottish UNESCO Digital Trail

Ed Forrest Galloway Southern Ayrshire UNESCO Biosphere UNESCO Trail • Scotland is home to 35 UNESCO sites and projects • 13 of these are physical sites that can be visited – 6 World Heritage Sites, 2 UNESCO Global Geoparks, 2 Biospheres and 3 Creative Cities • International Value of UNESCO Badge • Idea originated in 2016 • Steering group formed in 2018 • Chair - CEO SNH Franesca Osowska • UK National Commission for UNESCO • Visit Scotland • Representatives from the 13 UNESCO Designated Sites UNESCO Trail Sites in Scotland Biosphere Reserves World Heritage Sites • Galloway & Southern Ayrshire • The Forth Bridge • Wester Ross • Frontiers of the Roman Empire: Antonine Creative Cities Wall • Dundee UNESCO City of Design • Heart of Neolithic Orkney • Edinburgh UNESCO City of Literature • New Lanark • Glasgow UNESCO City of Music • Old and New Towns of Edinburgh Global Geoparks • St Kilda • Geopark Shetland • North West Highlands UNESCO Trail Proposal • Digital Trail linking together the 13 UNESCO sites • Web page for each UNESCO Trail Site • Focused on Sustainable Tourism • Promoting “World Class Scotland” • Association with other iconic Scottish sites • Part of a National and International Marketing Campaign The UNESCO Trail Offer…. Challenges • What is the Galloway and Southern Ayrshire UNESCO Biosphere Offer ? • Where can you visit to get a genuine Biosphere Experience? • Which businesses are acknowledging that they are in a UNESCO Biosphere? • Are there staff who have some understanding of the Biosphere designation? Explore the Biosphere Biosphere Experiences Biosphere Communities Biosphere Breaks UNESCO Trail • Questions….??? Networking • What are the USPs of the UNESCO Biosphere – our region – what do your customers rave about when they come to you? • Q1 – 15min Networking • So we have all these fantastic USPs how can we put them together to create a truly memorable day or multi day experience that will give visitors a real taste of what our UNESCO Biosphere represents? • Q2 – 15min. -

Campbell, RNB. 1987 Tail Deformities in Brown Trout from Acid And

Chapter (non‐refereed) Campbell, R.N.B.. 1987 Tail def ormities in brown trout from acid and acidified lochs in Scotland. In: Maitland, P. S . ; Lyle, A.A.; Campbell, R.N.B., (eds.) Acidification and fish in Scottish lochs. GrangeoverSands, Institute of Terrestrial Ecology, 5463. Copyright © 1987 NERC This version available at http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/11924/ NERC has developed NORA to enable users to access research outputs wholly or partially funded by NERC. Copyright and other rights for material on this site are retained by the authors and/or other rights owners. Users should read the terms and conditions of use of this material at http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/policies.html#access If you wish to cite this item please use the reference above or cite the NORA entry Contact CEH NORA team at [email protected] 64 Appendix 5 Tail deformities in brown trout from acid and acidified lochs in Scotland R N B CAMPBELL Summary Enoch (Plate 2) in Galloway (Traquair 1882) and later Most old records of tail deformities in brown trout from various streams in the central belt of Scotland proved to be from lochs which are now acidified and (Traquair 1892). The identical nature of the deformity fishless. Examination of trout from other lochs which reported from both Islay and Galloway was noted by are thought to be acidified but still have some trout Traquair (1892), but at the time, though it was felt that revealed significant deformities in the tails of some of the cause of the deformities was pollution, at least for these fish too. -

Cemeteries of Platform Cairns and Long Cists Around Sinclair's Bay

ProcCEMETERIES Soc Antiq Scot 141OF PLATFORM(2011), 125–143 CAIRNS AND LONG CISTS AROUND SINClair’s BaY, CAITHNESS | 125 Cemeteries of platform cairns and long cists around Sinclair’s Bay, Caithness Anna Ritchie* ABSTRACT The cemetery at Ackergill in Caithness has become the type site for Pictish platform cairns. A re- appraisal based on Society of Antiquaries of Scotland manuscripts, together with published sources, shows that, rather than comprising only the eight cairns and two long cists excavated by Edwards in the 1920s, the cemetery was more extensive. Close to Edwards’ site, Barry had already excavated two other circular cairns, three rectangular cairns and a long cist, and possibly another circular cairn was found between the two campaigns of excavation. Two of the cairns were re-used for subsequent burials, and two cairns were unique in having corbelled chambers built at ground level. Other burial sites along the shore of Sinclair’s Bay are also examined. INTRODUCTION accounts by A J H Edwards of cairns and long cists at Ackergill on Sinclair’s Bay For more than a century after it was founded in Caithness (1926; 1927). These included in 1780, the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland square and circular platform cairns of the type was the primary repository in Scotland for that is thought to have been used in Pictish information about sites and artefacts, some times, for which Ackergill remains the type but not all of which were published in the site, and the new information presented here Transactions (Archaeologia Scotica) or in helps both to clarify Ackergill itself and to the Proceedings. -

Issued Authorisations 2019-2020 (As at 9Th August 2019)

Issued Authorisations 2019-2020 (as at 9th August 2019) The following table shows specific authorisations issued covering the period 1st April 2019 to 31st March 2020. This table will be updated throughout the 2018-2019 authorisation year. Auth No Type Approval for (woodland, Natural Area / control Area / Property Deer Management Group Start Date End Date Heritage, Agri etc) 13968 5(6) Unenclosed Woodland Mam Mor Forest None 26/03/2019 31/03/2020 13969 5(6) Unenclosed Woodland/Natural Kinveachy Hill Monadliaths 01/04/2019 31/03/2020 Heritage 13973 5(6) Unenclosed Woodland/Natural Wildland Strathmore, Hope, Kinloch, North West Sutherland 09/04/2019 31/03/2020 Heritage Loyal 13978 5(6) Unenclosed Woodland Kenmore and Furnace None 01/04/2019 31/03/2020 13983 5(6) Public Safety Laggan Islay 01/04/2019 31/03/2020 13989 5(6) Unenclosed Woodland/Natural FCS Western District various; Mull, Blackmount, Inverary 01/04/2019 31/03/2020 Heritage & Tyndrum,Knoydart, West Lochaber, Monadhliaths, Midwest, Blackmount, Ardnamurchan 13990 18(2) Woodland FCS Western District various; Mull, Blackmount, Inverary 01/10/2019 31/03/2020 & Tyndrum,Knoydart, West Lochaber, Monadhliaths, Midwest, Blackmount, Ardnamurchan 13993 5(6) Unenclosed Woodland Keam Farm None 01/04/2019 31/03/2020 13994 18(2) Woodland Keam Farm None 01/04/2019 31/03/2020 13995 5(6) Unenclosed Woodland Ribreck Wood None 01/04/2019 31/03/2020 13996 5(6) Unenclosed Woodland FCS Cowal Cowal 01/04/2019 31/03/2020 13997 18(2) Woodland FCS Cowal Cowal 01/10/2019 31/03/2020 13998 5(6) Unenclosed -

SHAPE Newsletter 2018 2.Pdf

Sustainable Heritage Areas: Partnerships for Ecotourism NEWSLETTER 2018/2 SHAPE NEWSLETTER 2018/2 1 SUSTAINABLE HERTITAGE AREAS: PARTNERSHIPS FOR ECO-TOURISM Yes, we are moving ahead! Welcome to the second SHAPE newsletter, which is being published just after our third partner meeting in Wester Ross, Scotland. After a year of activity, SHAPE is very much moving forward and evolving in positive directions. Project partners in each of our SHAs have organized meetings with stakeholders to map natural and cultural heritage assets and identify possible joint initiatives. There has been strong interest in these meetings; about 200 people have attended them. Stakeholders have used a range of different methods for mapping assets, which will all be included in our e-service, to be launched later this year. The initiatives that have emerged from the lively discussion in the meetings fall into five main themes: trails, branding, training (especially young people), local products (in particular, those made from wool), and wildlife watching. These initiatives will be developed over the next year and also form the basis of learning journeys next spring and summer. This newsletter provides further detail on the meetings in each SHA; the partner meeting, to which we were glad to invite representatives from five other NPA projects; and two reports prepared by Laura Ferguson, who has been an important member of our team for the past year. We hope you find much of interest! Professor Martin Price Director, Centre for Mountain Studies, Perth College, University of the Highlands & Islands Chairholder, UNESCOI Chair in Sustainable Mountain Development Cover: Torridon, Wester Ross. -

DUMFRIESSHIRE and GALLOWAY NATURAL HISTORY and ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY

TRANSACTIONS of the DUMFRIESSHIRE AND GALLOWAY NATURAL HISTORY and ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY LXXXVII VOLUME 87 2013 TRANSACTIONS of the DUMFRIESSHIRE AND GALLOWAY NATURAL HISTORY and ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY FOUNDED 20 NOVEMBER 1862 THIRD SERIES VOLUME 87 LXXXVII Editors: ELAINE KENNEDY FRANCIS TOOLIS JAMES FOSTER ISSN 0141-1292 2013 DUMFRIES Published by the Council of the Society Office-Bearers 2012-2013 and Fellows of the Society President Dr F. Toolis FSA Scot Vice Presidents Mrs C. Iglehart, Mr A. Pallister, Mr D. Rose and Mr L. Murray Fellows of the Society Mr A.D. Anderson, Mr J.H.D. Gair, Dr J.B. Wilson, Mr K.H. Dobie, Mrs E. Toolis, Dr D.F. Devereux and Mrs M. Williams Mr L.J. Masters and Mr R.H. McEwen — appointed under Rule 10 Hon. Secretary Mr J.L. Williams, Merkland, Kirkmahoe, Dumfries DG1 1SY Hon. Membership Secretary Miss H. Barrington, 30 Noblehill Avenue, Dumfries DG1 3HR Hon. Treasurer Mr M. Cook, Gowanfoot, Robertland, Amisfield, Dumfries DG1 3PB Hon. Librarian Mr R. Coleman, 2 Loreburn Park, Dumfries DG1 1LS Hon. Editors Mrs E. Kennedy, Nether Carruchan, Troqueer, Dumfries DG2 8LY Dr F. Toolis, 25 Dalbeattie Road, Dumfries DG2 7PF Dr J. Foster (Webmaster), 21 Maxwell Street, Dumfries DG2 7AP Hon. Syllabus Conveners Mrs J. Brann, Troston, New Abbey, Dumfries DG2 8EF Miss S. Ratchford, Tadorna, Hollands Farm Road, Caerlaverock, Dumfries DG1 4RS Hon. Curators Mrs J. Turner and Miss S. Ratchford Hon. Outings Organiser Mrs S. Honey Ordinary Members Mrs P.G. Williams, Mrs A. Weighill, Dr Jeanette Brock, Dr Jeremy Brock, Mr D. Scott, Mr J.