Young-FAI-2016-The-Evolution-Of-The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North East Scotland

Employment Land Audit 2018/19 Aberdeen City Council Aberdeenshire Council Employment Land Audit 2018/19 A joint publication by Aberdeen City Council and Aberdeenshire Council Executive Summary 1 1. Introduction 1.1 Purpose of Audit 5 2. Background 2.1 Scotland and North East Scotland Economic Strategies and Policies 6 2.2 Aberdeen City and Shire Strategic Development Plan 7 2.3 Aberdeen City and Aberdeenshire Local Development Plans 8 2.4 Employment Land Monitoring Arrangements 9 3. Employment Land Audit 2018/19 3.1 Preparation of Audit 10 3.2 Employment Land Supply 10 3.3 Established Employment Land Supply 11 3.4 Constrained Employment Land Supply 12 3.5 Marketable Employment Land Supply 13 3.6 Immediately Available Employment Land Supply 14 3.7 Under Construction 14 3.8 Employment Land Supply Summary 15 4. Analysis of Trends 4.1 Employment Land Take-Up and Market Activity 16 4.2 Office Space – Market Activity 16 4.3 Industrial Space – Market Activity 17 4.4 Trends in Employment Land 18 Appendix 1 Glossary of Terms Appendix 2 Employment Land Supply in Aberdeen and map of Aberdeen City Industrial Estates Appendix 3 Employment Land Supply in Aberdeenshire Appendix 4 Aberdeenshire: Strategic Growth Areas and Regeneration Priority Areas Appendix 5 Historical Development Rates in Aberdeen City & Aberdeenshire and detailed description of 2018/19 completions December 2019 Aberdeen City Council Aberdeenshire Council Strategic Place Planning Planning and Environment Marischal College Service Broad Street Woodhill House Aberdeen Westburn Road AB10 1AB Aberdeen AB16 5GB Aberdeen City and Shire Strategic Development Planning Authority (SDPA) Woodhill House Westburn Road Aberdeen AB16 5GB Executive Summary Purpose and Background The Aberdeen City and Shire Employment Land Audit provides up-to-date and accurate information on the supply and availability of employment land in the North-East of Scotland. -

Economy, Energy and Tourism Committee

ECONOMY, ENERGY AND TOURISM COMMITTEE Wednesday 8 October 2008 Session 3 £5.00 Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body 2008. Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to the Licensing Division, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ Fax 01603 723000, which is administering the copyright on behalf of the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body. Produced and published in Scotland on behalf of the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body by RR Donnelley. CONTENTS Wednesday 8 October 2008 Col. INTERESTS...................................................................................................................................................... 1079 BUDGET PROCESS 2009-10 ............................................................................................................................ 1080 CREDIT CRUNCH (IMPACT ON SCOTTISH ECONOMY) ......................................................................................... 1113 COUNCIL OF ECONOMIC ADVISERS (INVITATION) .............................................................................................. 1118 SCOTTISH TRADES UNION CONGRESS (SEMINAR) ............................................................................................ 1123 ECONOMY, ENERGY AND TOURISM COMMITTEE 19th Meeting 2008, Session 3 CONVENER *Iain Smith (North East Fife) (LD) DEPUTY CONVENER *Rob Gibson (Highlands and Islands) (SNP) COMMITTEE MEMBERS *Ms Wendy Alexander (Paisley North) (Lab) *Gavin Brown (Lothians) -

From Oil Wealth to Green Growth

From oil wealth to green growth An empirical agent-based model of recession, migration and sustainable urban transition Jiaqi Ge1, Gary Polhill1, Tony Craig1, Nan Liu2 1 The James Hutton Institute 2 University of Aberdeen Abstract This paper develops an empirical, multi-layered and spatially-explicit agent-based model that explores sustainable pathways for Aberdeen City and surrounding area to transition from an oil- based economy to green growth. The model takes an integrated, complex system approach to urban systems and incorporates the interconnectedness between people, households, businesses, industries and neighbourhoods. We find that the oil price collapse could potentially lead to enduring regional decline and recession. With green growth, however, the crisis could be used as an opportunity to restructure the regional economy, reshape its neighbourhoods, and redefine its identity in the global economy. We find that the type of the green growth and the location of the new businesses will have profound ramifications for development outcomes, not only by directly creating businesses and employment opportunities in strategic areas, but also by redirecting households and service businesses to these areas. New residential and business centres emerge as a result of this process. Finally, we argue that industries, businesses and the labour market are essential components of a deeply integrated urban system. To understand urban transition, models should consider both household and industrial aspects. Highlights • An empirical, multi-layered -

The Attlee Governments

Vic07 10/15/03 2:11 PM Page 159 Chapter 7 The Attlee governments The election of a majority Labour government in 1945 generated great excitement on the left. Hugh Dalton described how ‘That first sensa- tion, tingling and triumphant, was of a new society to be built. There was exhilaration among us, joy and hope, determination and confi- dence. We felt exalted, dedication, walking on air, walking with destiny.’1 Dalton followed this by aiding Herbert Morrison in an attempt to replace Attlee as leader of the PLP.2 This was foiled by the bulky protection of Bevin, outraged at their plotting and disloyalty. Bevin apparently hated Morrison, and thought of him as ‘a scheming little bastard’.3 Certainly he thought Morrison’s conduct in the past had been ‘devious and unreliable’.4 It was to be particularly irksome for Bevin that it was Morrison who eventually replaced him as Foreign Secretary in 1951. The Attlee government not only generated great excitement on the left at the time, but since has also attracted more attention from academics than any other period of Labour history. Foreign policy is a case in point. The foreign policy of the Attlee government is attractive to study because it spans so many politically and historically significant issues. To start with, this period was unique in that it was the first time that there was a majority Labour government in British political history, with a clear mandate and programme of reform. Whereas the two minority Labour governments of the inter-war period had had to rely on support from the Liberals to pass legislation, this time Labour had power as well as office. -

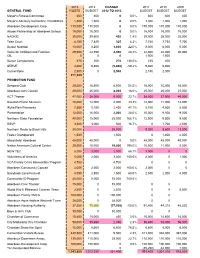

2013 2012 Change 2011 2010 2009 General Fund Rqstd

2013 2012 CHANGE 2011 2010 2009 GENERAL FUND RQSTD BUDGET 2012 TO 2013 BUDGET BUDGET BUDGET Mayor's Fitness Committee 600 600 0 0.0% 600 600 600 Mayor's Advisory Committee / Disabilities 1,300 1,300 0 0.0% 1,300 1,000 1,000 Aberdeen Development Corp. 170,000 170,000 0 0.0% 170,000 170,000 170,000 Abuse Partnership w/ Aberdeen School 15,000 15,000 0 0.0% 15,000 15,000 15,000 NADRIC 30,000 29,600 400 1.4% 29,000 28,000 25,000 Teen Court 8,150 7,825 325 4.2% 7,740 7,735 7,700 Senior Nutrition 10,000 8,200 1,800 22.0% 8,000 6,000 5,000 Voice for Children and Families 29,500 24,550 4,950 20.2% 24,000 22,000 20,000 OIL 0 0 0 1,500 1,500 Senior Companions 470 200 270 135.0% 425 400 SERVE 4,000 9,800 (5,800) -59.2% 9,600 9,600 Cornerstone 2,500 0 2,500 2,150 2,000 271,520 PROMOTION FUND Sertoma Club 25,000 16,500 8,500 51.5% 16,000 15,000 16,000 Aberdeen Arts Council 29,000 25,000 4,000 16.0% 25,000 25,000 27,000 ACT Theater 47,000 38,000 9,000 23.7% 38,000 37,000 40,000 Dacotah Prairie Museum 16,000 12,000 4,000 33.3% 12,000 11,000 12,000 Wylie Park Fireworks 7,500 5,100 2,400 47.1% 5,100 4,600 5,500 Presentation 12,000 10,000 2,000 20.0% 10,000 9,500 9,500 Northern State Foundation 40,000 15,000 25,000 166.7% 12,500 9,500 9,500 RSVP 3,500 3,000 500 16.7% 0 1,700 2,500 Northern Route to Black Hills 25,000 25,000 9,000 8,600 13,000 Foster Grandparent 1,500 1,500 0 1,400 2,000 Absolutely! Aberdeen 48,000 48,000 0 0.0% 48,000 48,000 40,000 Native American Cultural Center 29,500 10,000 19,500 195.0% 10,000 11,000 5,000 NEW TEC 5,000 3,000 2,000 -

OFFICIAL GUIDE for Winches and Deck Machinery Torque to the Experts Engineering Services Ltd

OFFICIAL GUIDE For winches and deck machinery torque to the experts Engineering Services Ltd Belmar Engineering is one of the most advanced sub contract precision engineering workshops servicing the Oil and Gas industries in the North Sea and world-wide. An imaginative and on-going programme of reinvestment in computer based technology has meant that Belmar Engineering work at the very frontiers of technology. We are quite simply the most precise of precision engineering companies. Our Services Belmar offer a complete engineering service to BS EN ISO 9001(2000) and ISO 14001(2004). Please visit our website for detailed pages of machining capacities, inspection and gauges below: Milling Section. Turning Section. Machine shop support. Quality Assurance. Weld cladding equipment. The Deck Machinery Specialists: ACE Winches is a global specialist in the design, Engineering design & project management manufacture and hire of hydraulic winches and deck machinery for the offshore oil and gas, All sizes of winches for sale & hire marine and renewable energy markets. Bespoke manufacturing solutions available Specialist offshore personnel hire We deliver exceptional service and performance for our clients in the world’s harshest operating environments and we always endeavour to Hydraulic sales & service exceed our clients’ expectations while maintaining our excellent record of quality and safety. Spooling winch hire About us How we operate Our people 750 tonne winch test bed facility ACE Hire Equipment offers a comprehensive range of winch and deck machinery equipment for use on floating vessels, offshore installations Wire rope & umbilical spooling facility Belmar offers a comprehensive Belmar Engineering was formed in One third of our workforce have and land-based projects. -

Silicon Cities Silicon Cities Supporting the Development of Tech Clusters Outside London and the South East of England

Policy Exchange Policy Silicon Cities Cities Silicon Supporting the development of tech clusters outside London and the South East of England Eddie Copeland and Cameron Scott Silicon Cities Supporting the development of tech clusters outside London and the South East of England Eddie Copeland and Cameron Scott Policy Exchange is the UK’s leading think tank. We are an educational charity whose mission is to develop and promote new policy ideas that will deliver better public services, a stronger society and a more dynamic economy. Registered charity no: 1096300. Policy Exchange is committed to an evidence-based approach to policy development. We work in partnership with academics and other experts and commission major studies involving thorough empirical research of alternative policy outcomes. We believe that the policy experience of other countries offers important lessons for government in the UK. We also believe that government has much to learn from business and the voluntary sector. Trustees Daniel Finkelstein (Chairman of the Board), David Meller (Deputy Chair), Theodore Agnew, Richard Briance, Simon Brocklebank-Fowler, Robin Edwards, Richard Ehrman, Virginia Fraser, David Frum, Edward Heathcoat Amory, Krishna Rao, George Robinson, Robert Rosenkranz, Charles Stewart-Smith and Simon Wolfson. About the Authors Eddie Copeland – Head of Unit @EddieACopeland Eddie joined Policy Exchange as Head of the Technology Policy Unit in October 2013. Previously he has worked as Parliamentary Researcher to Sir Alan Haselhurst, MP; Congressional intern to Congressman Tom Petri and the Office of the Parliamentarians; Project Manager of global IT infrastructure projects at Accenture and Shell; Development Director of The Perse School, Cambridge; and founder of web startup, Orier Digital. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

GRI-Rapport 2016:2 Bank Management

Gothenburg Research Institute GRI-rapport 2016:2 Bank Management Banks and their world view contexts Sten Jönsson © Gothenburg Research Institute All rights reserved. No part of this report may be repro- duced without the written permission from the publisher. Gothenburg Research Institute School of Business, Economics and Law at University of Gothenburg P.O. Box 600 SE-405 30 Göteborg Tel: +46 (0)31 - 786 54 13 Fax: +46 (0)31 - 786 56 19 E-post: [email protected] ISSN 1400-4801 Layout: Henric Karlsson Banks and their world view contexts By Sten Jönsson Gothenburg Research Institute (GRI) School of Business, Economics and Law University of Gothenburg Contents Introduction 8 1. Preliminaries 13 1.1. Theoretical orientation 13 1.2. What is a bank anyway? 15 1.3. The changing nature of arbitrage 16 1.4. A quick tour of the world views that set the stage for banking 18 2. Greed, arbitrage, and decency in action 22 2.1. Greed – the original sin! 22 2.2. An overview of wealth and the afterlife during the first centuries AD 24 3. Scholasticism – guiding individuals to proper use of their free will 26 4. The most prominent banks – watched by the scholastics 32 4.1. Medici 32 4.2. Fugger 37 5. Mercantilism – the origins of political economy and, consequently, of economic policy 42 5.1. The glory and decline of merchant banks 45 6. Neoliberalim started with the Austrian School 59 6.1. Modernism and crumbling empires 59 6.2. The context in which the Austrian school developed 61 6.3. -

Jak Rozwijać Klaster

Jak rozwija ć klaster - praktyczny przewodnik Jak rozwija ć klaster - praktyczny przewodnik DTI nap ędza nasze ambicje -„bogactwo dla wszystkich” poprzez prace na rzecz stworzenia lepszego środowiska sukcesu biznesowego w Wielkiej Brytanii. Pomagamy ludziom i przedsi ębiorstwom w osi ągni ęciu wi ększej produktywno ści poprzez promowanie przedsiębiorstw, innowacyjno ści oraz kreatywno ści. Wspieramy brytyjski biznes w kraju i zagranic ą. Silnie inwestujemy w światowej klasy nauk ę oraz technologie. Chronimy prawa ludzi pracuj ących oraz konsumentów. Opowiadamy si ę za uczciwymi i otwartymi rynkami w Wielkiej Brytanii, Europie i na całym świecie. 2 Jak rozwija ć klaster - praktyczny przewodnik dti Jak rozwija ć klaster - Praktyczny Przewodnik Raport przygotowany dla Departamentu Handlu i Przemysłu oraz angielskich Regionalnych Agencji Rozwoju (RDAs) przez firm ę Ecotec Research & Consulting 3 Jak rozwija ć klaster - praktyczny przewodnik SPIS TRE ŚCI SPIS TRE ŚCI Przedmowa 5 1. Wprowadzen 7 ie CZ ĘŚĆ A Strategia klastra 2. Rozwój strategii opartych na klastrach 12 3. Mierzenie (ocena) rozwoju klastrów 19 CZ ĘŚĆ B: ‘Co działa”?: Polityka działania w celu wspierania klastrów 4. Krytyczne czynniki sukcesu 25 5. Czynniki wspieraj ące oraz polityki sukcesu 43 6. Instrumenty komplementarne oraz uwarunkowania polityki sukcesu 54 ZAL ĄCZNIKI A: Przypisy 58 B: Bibliografia 61 C: Słowniczek 69 D: Konsultanci 77 E: Poradnik oceny rozwoju klastra 79 4 Jak rozwij ać klaster - pra ktyc zny przewo dnik Lord Sainsbury PRZEDMOWA W zglobalizowanym i technologicznie zaawansowanym świecie, przedsi ębiorstwa coraz cz ęś ciej ł ącz ą si ę w celu wygenerowania wi ększej konkurencyjno ści. To zjawisko – klastrowanie (clustering) – jest widoczne na całym świecie. -

Preliminary Announcement of 2003 Annual Results the ROYAL BANK of SCOTLAND GROUP Plc

Annual Results 2003 Preliminary Announcement of 2003 Annual Results THE ROYAL BANK OF SCOTLAND GROUP plc CONTENTS Page Results summary 2 2003 Highlights 3 Group Chief Executive's review 4 Financial review 8 Summary consolidated profit and loss account 11 Divisional performance 12 Corporate Banking and Financial Markets 13 Retail Banking 15 Retail Direct 17 Manufacturing 18 Wealth Management 19 RBS Insurance 20 Ulster Bank 22 Citizens 23 Central items 25 Average balance sheet 26 Average interest rates, yields, spreads and margins 27 Statutory consolidated profit and loss account 28 Consolidated balance sheet 29 Overview of consolidated balance sheet 30 Statement of consolidated total recognised gains and losses 32 Reconciliation of movements in consolidated shareholders' funds 32 Consolidated cash flow statement 33 Notes 34 Additional analysis of income, expenses and provisions 40 Asset quality 41 Analysis of loans and advances to customers 41 Cross border outstandings 42 Selected country exposures 42 Risk elements in lending 43 Provisions for bad and doubtful debts 44 Market risk 46 Regulatory ratios and other information 47 Additional financial data for US investors 48 Forward-looking statements 49 Contacts 50 1 THE ROYAL BANK OF SCOTLAND GROUP plc RESULTS SUMMARY 2003 2002 Increase £m £m £m % Total income 19,229 16,815 2,414 14% --------- --------- ------- Operating expenses* 8,389 7,669 720 9% -------- ------- ----- Operating profit before provisions* 8,645 7,796 849 11% -------- ------- ----- Profit before tax, goodwill amortisation and integration costs 7,151 6,451 700 11% -------- -------- ----- Profit before tax 6,159 4,763 1,396 29% -------- -------- ------- Cost:income ratio** 42.0% 44.0% --------- --------- Basic earnings per ordinary share 79.0p 68.4p 10.6p 15% -------- -------- ------- Adjusted earnings per ordinary share 159.3p 144.1p 15.2p 11% --------- --------- ------- Dividends per ordinary share 50.3p 43.7p 6.6p 15% -------- -------- ------ * excluding goodwill amortisation and integration costs. -

“The Scottish Executive Is Open for Business”

10 | VARIANT 26 | SUMMER 2006 “The Scottish Executive is open for business” The New Regeneration Statement, The Royal Bank of Scotland & the Community Voices Network Chik Collins Introduction: effort is being made to intensify the application growth opportunities for Scottish firms, such as service of the neo-liberal agenda across Scotland. But providers, in the future”.7 “Ministers felt the need to say the strategy adopted means there are particular So, as is the philosophy in the Royal Bank, something about regeneration” implications for the poorest communities – thus the message is very clear. The public sector can The language of civil servants can be provocatively ministers’ curious “need to say something about influence company growth through privatisation obscure. So it was when Alisdair McIntosh, head regeneration”. People and Place is not more of the and liberalisation – with health and education of regeneration in the Scottish Executive, came to ‘same old regeneration partnership stuff’, but a high on the list. The aim is to ‘grow’ a Stagecoach Glasgow University at the beginning of March to key part of a broader agenda for a step change or two in these sectors. Public sector failure to speak about the latest “regeneration statement” in opening up Scotland’s communities to private positively ‘influence’ this process will undermine – People and Place.1 He said it had been produced sector penetration. This agenda can do immense the nation’s competitiveness in the global because ministers had “felt the need to say damage across Scotland – but with particularly economy. something about regeneration”, and that they had unsavoury implications for the poorest From a more critical perspective we might say felt this need as early as 2003.