Daniel Lunney,1 Allan Fox,2 Peter Catling,3 Harry Recher 4 and Henry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOCALITY MAP Compartment 720 Nullica State Forest No.545 SOUTHERN REGION: EDEN MANAGEMENT AREA BOGGY CREEK Scale: 1:100,000

Bournda NR LOCALITY MAP Compartment 720 Nullica State Forest No.545 SOUTHERN REGION: EDEN MANAGEMENT AREA BOGGY CREEK Scale: 1:100,000 MERIMBULA LAKE Á Pambula ! Ben Boyd NP! Á Á Dobbyns Road PAMBULA RIVER P" YOWAKA RIVER G PAMBULA LAKE 720 Egan Peaks NR South East Forest NP PALESTINE CREEK CURALO LAGOON Eden ! Towns & Localities ! Sealed Road Major Rivers® Major Forest Road COCORA LAGOON State Forest National Parks SHADRACHS CREEK Planning Unit Formal Reserve Vacant CrownLand Informal Reserve NonForest Waterbodies Freehold NULLICA RIVER G Emergency Meeting Point Á Evacuation Route LEOS CREEK REEDY CREEK Haulage Route P" Helicopter Landing Site Á BOYDTOWN CREEK TOWAMBA RIVER Mount Imlay NP Prepared By: AndrewKemsley Harvest Plan Operational Map Compartment: 720 Version: 1 .................RE....G.I...O.NA.....L... M....ANA.........G.E...R.... A.PP.....R...O....V.AL................... State Forest: Nullica No: 545 APPROVED: DANIEL TUAN SOUTHERN REGION - Native Forests ³ DATE: 05/07/2012 Map Sheet: EDEN 8824-2S 45 46 47 A X 05 05 ^! ^ XX XX JA ^ CH # 720-3 Rd H B H 0# 3 HHS3 2 D 0# ú G B 0#0# H BB 1 720-6 Rd S2 BB 04 ú FH ^ 04 H L ^ J XX ^! KH ú E 4 0# S1 0# ^! JH B # úC1 B B É BB I J XX 03 745000E 46 47 BOUNDARIES NONHARVEST AREA FAUNA FEATURES ÉÉÉÉÉÉCompartment Boundary Special Management - FMZ 2 A PowerfulOwl ÉÉÉÉÉÉCoupe Boundary (100m either side) ^ Gang Gang Cockatoo Smoky Mouse Exclusion Area ^! Smoky Mouse ROADS Ridge & HeadwaterHabitat (80m) X Yellow-bellied Glider Major Forest # 32> Excluded Forest Varied Sittella Minor Forest Rocky Outcrop (0.1-0.5 ha, 20m) ^ Glossy Black-Cockatoo EPL Standard Existing (Major) X EPL Standard Existing (Minor) Cliff and buffer (20m) X Yellow-bellied Glider (Heard) EPL Licenced (New Construction) Slopes >30 (IHL4) ^ Eastern Pigmy Possum DRAINAGE FEATURE PROTECTION (EPL DUMPS & CROSSINGS FLORA FEATURES IHL 2 & TSL). -

The Canberra • B Ush Walking Club ( Inc. Newsletter

THE CANBERRA • B USH WALKING CLUB ( INC. NEWSLETTER GPO Box 160, Canberra ACT 2601 VOLUME 36 October 2000 NUMBER 10 OCTOBER GENERAL MEETING 8pm Wednesday 18th Speaker: Betty Kitchener, on 'Field First Aid' Woden Library Community Room Make the most of the evening and join other members at 6. OOpm for a convivial meal at the Chinese Kitchen 6)10 Restaurant in Corinna Street, Shop 091, Woden Plaza, Phi/lip. to be early to ensure there will be ample time to finish and still get to the meeting in good ti PRESIDENT'S • Membership fees have been increased to $25 (single) and Also In This Issue: PRATTLE $33 (household) Item Page • The Club transport rate has PRESIDENT'S PRATTLE For those of you who were unable been increased to to make last month's Annual Gen- MEMBERSHIP MATTERS 2 30cents/kilometrelvehicle. eral Meeting, the key outcomes are MOTIONS PASSED AT AGM 2 as follows: Contact details for the Committee " are shown on the back page of each 39 ANNUAL REPORT 2 We have four brand new Com- It. Please don't hesitate to give us a CBC 40th ANNIVERSARY 4 mittee members - Ailsa Brown call if you have concerns about the TRIP PREVIEWS 4 (Publisher), Michael Macona- way we are doing things or have chie (Conservation Officer), some suggestions for how we might WALKS WAFFLE 5 Michael Sutton (Treasurer), do things better. A bit of praise LETTERS TO THE EDITOR. 6 and Rosanne Walker (Social from time to time helps keep us TRIP REPORTS 7 Secretary), replacing Vance going so do let us know if we do Brown, Janet Edstein, Cate something that pleases you. -

NPWS Pocket Guide 3E (South Coast)

SOUTH COAST 60 – South Coast Murramurang National Park. Photo: D Finnegan/OEH South Coast – 61 PARK LOCATIONS 142 140 144 WOLLONGONG 147 132 125 133 157 129 NOWRA 146 151 145 136 135 CANBERRA 156 131 148 ACT 128 153 154 134 137 BATEMANS BAY 139 141 COOMA 150 143 159 127 149 130 158 SYDNEY EDEN 113840 126 NORTH 152 Please note: This map should be used as VIC a basic guide and is not guaranteed to be 155 free from error or omission. 62 – South Coast 125 Barren Grounds Nature Reserve 145 Jerrawangala National Park 126 Ben Boyd National Park 146 Jervis Bay National Park 127 Biamanga National Park 147 Macquarie Pass National Park 128 Bimberamala National Park 148 Meroo National Park 129 Bomaderry Creek Regional Park 149 Mimosa Rocks National Park 130 Bournda National Park 150 Montague Island Nature Reserve 131 Budawang National Park 151 Morton National Park 132 Budderoo National Park 152 Mount Imlay National Park 133 Cambewarra Range Nature Reserve 153 Murramarang Aboriginal Area 134 Clyde River National Park 154 Murramarang National Park 135 Conjola National Park 155 Nadgee Nature Reserve 136 Corramy Regional Park 156 Narrawallee Creek Nature Reserve 137 Cullendulla Creek Nature Reserve 157 Seven Mile Beach National Park 138 Davidson Whaling Station Historic Site 158 South East Forests National Park 139 Deua National Park 159 Wadbilliga National Park 140 Dharawal National Park 141 Eurobodalla National Park 142 Garawarra State Conservation Area 143 Gulaga National Park 144 Illawarra Escarpment State Conservation Area Murramarang National Park. Photo: D Finnegan/OEH South Coast – 63 BARREN GROUNDS BIAMANGA NATIONAL PARK NATURE RESERVE 13,692ha 2,090ha Mumbulla Mountain, at the upper reaches of the Murrah River, is sacred to the Yuin people. -

Australasian Bat Society Newsletter

The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter Number 21 November 2003 ABS Website: http://abs.ausbats.org.au ABS Listserver: [email protected] ISSN 1448-5877 The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter, Number 21, Nov 2003 – Instructions for Contributors – The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter will accept contributions under one of the following two sections: Research Papers, and all other articles or notes. There are two deadlines each year: 31 st March for the April issue, and 31 st October for the November issue. The Editor reserves the right to hold over contributions for subsequent issues of the Newsletter , and meeting the deadline is not a guarantee of immediate publication. Opinions expressed in contributions to the Newsletter are the responsibility of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Australasian Bat Society, its Executive or members. For consistency, the following guidelines should be followed: • Emailed electronic copy of manuscripts or articles, sent as an attachment, is the preferred method of submission. Manuscripts can also be sent on 3½” floppy disk preferably in IBM format. Faxed and hard copy manuscripts will be accepted but reluctantly! Please send all submissions to the Newsletter Editor at the email or postal address below. • Electronic copy should be in 11 point Arial font, left and right justified with 16 mm left and right margins. Please use Microsoft Word; any version is acceptable. • Manuscripts should be submitted in clear, concise English and free from typographical and spelling errors. Please leave two spaces after each sentence. • Research Papers should include: Title; Names and addresses of authors; Abstract (approx. -

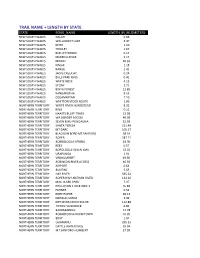

Trail Name + Length by State

TRAIL NAME + LENGTH BY STATE STATE ROAD_NAME LENGTH_IN_KILOMETERS NEW SOUTH WALES GALAH 0.66 NEW SOUTH WALES WALLAGOOT LAKE 3.47 NEW SOUTH WALES KEITH 1.20 NEW SOUTH WALES TROLLEY 1.67 NEW SOUTH WALES RED LETTERBOX 0.17 NEW SOUTH WALES MERRICA RIVER 2.15 NEW SOUTH WALES MIDDLE 40.63 NEW SOUTH WALES NAGHI 1.18 NEW SOUTH WALES RANGE 2.42 NEW SOUTH WALES JACKS CREEK AC 0.24 NEW SOUTH WALES BILLS PARK RING 0.41 NEW SOUTH WALES WHITE ROCK 4.13 NEW SOUTH WALES STONY 2.71 NEW SOUTH WALES BINYA FOREST 12.85 NEW SOUTH WALES KANGARUTHA 8.55 NEW SOUTH WALES OOLAMBEYAN 7.10 NEW SOUTH WALES WHITTON STOCK ROUTE 1.86 NORTHERN TERRITORY WAITE RIVER HOMESTEAD 8.32 NORTHERN TERRITORY KING 0.53 NORTHERN TERRITORY HAASTS BLUFF TRACK 13.98 NORTHERN TERRITORY WA BORDER ACCESS 40.39 NORTHERN TERRITORY SEVEN EMU‐PUNGALINA 52.59 NORTHERN TERRITORY SANTA TERESA 251.49 NORTHERN TERRITORY MT DARE 105.37 NORTHERN TERRITORY BLACKGIN BORE‐MT SANFORD 38.54 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROPER 287.71 NORTHERN TERRITORY BORROLOOLA‐SPRING 63.90 NORTHERN TERRITORY REES 0.57 NORTHERN TERRITORY BOROLOOLA‐SEVEN EMU 32.02 NORTHERN TERRITORY URAPUNGA 1.91 NORTHERN TERRITORY VRDHUMBERT 49.95 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROBINSON RIVER ACCESS 46.92 NORTHERN TERRITORY AIRPORT 0.64 NORTHERN TERRITORY BUNTINE 5.63 NORTHERN TERRITORY HAY RIVER 335.62 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROPER HWY‐NATHAN RIVER 134.20 NORTHERN TERRITORY MAC CLARK PARK 7.97 NORTHERN TERRITORY PHILLIPSON STOCK ROUTE 55.84 NORTHERN TERRITORY FURNER 0.54 NORTHERN TERRITORY PORT ROPER 40.13 NORTHERN TERRITORY NDHALA GORGE 3.49 NORTHERN TERRITORY -

EIS 1767 AA066857 Assessment of Mineral Resouru's in the Eden CRA

EIS 1767 AA066857 Assessment of mineral resouru's in the Eden CRA study area MSW DEPT P1KARY IUS1RIES AA066857 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 :0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ( 0 0 0 0 0 I 0 ( 0 I I I I I Assessment of Mineral Resources in the Eden CRA Study Area A report undertaken for the NSW CRAIRFA Steering Committee 27 February 1998 ASSESSMENT OF MINERAL RESOURCES IN THE EDEN CRA STUDY AREA BUREAU OF RESOURCE SCIENCES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF NSW DEPARTMENT OF MINERAL RESOURCES A report undertaken for the NSW CRA/RFA Steering Committee Project Number NE 08/ES 27 February 1998 REPORT STATUS This report has been prepared as a working paper for the NSW CRAIRFA Steering Committee under the direction of the Economic and Social Technical Committee. It is recognised that it may contain errors that require correction but it is released to be consistent with the principle that information related to the comprehensive regional assessment process in New South Wales will be made publicly available. For more information and for information on access to data contact the: Resource and Conservation Division, Department of Urban Affairs and Planning GPO Box 3927 SYDNEY NSW 2001 Phone: (02) 9228 3166 Fax: (02) 9228 4967 Forests Taskforce, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet 3-5 National Circuit BARTON ACT 2600 Phone: 1800 650 983 Fax: (02) 6271 5511 © Crown copyright [June 1997] This project has been jointly funded by the New South Wales and Commonwealth Governments. The work undertaken within this project has been managed by the joint NSW / Commonwealth CRAIRFA Steering Committee which includes representatives from the NSW and Commonwealth Governments and stakeholder groups. -

Walk-Issue14-1963.Pdf

1963 Terms and Conditions of Use Copies of Walk magazine are made available under Creative Commons - Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike copyright. Use of the magazine. You are free: • To Share- to copy, distribute and transmit the work • To Remix- to adapt the work Under the following conditions (unless you receive prior written authorisation from Melbourne Bushwalkers Inc.): • Attribution- You must attribute the work (but not in any way that suggests that Melbourne Bushwalkers Inc. endorses you or your use of the work). • Noncommercial- You may not use this work for commercial purposes. • Share Alike- If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. Disclaimer of Warranties and Limitations on Liability. Melbourne Bushwalkers Inc. makes no warranty as to the accuracy or completeness of any content of this work. Melbourne Bushwalkers Inc. disclaims any warranty for the content, and will not be liable for any damage or loss resulting from the use of any content. ----···············------------------------------· • BUSHWALKING • CAVING • ROCK CLIMBING • CAMPING • SKI TOURING PROVIDE A CHALLENGE TO MAN AND HIS EQUIPMENT, FOR OVER 30 YEARS, PADDYMADE CAMP GEAR HAS PROVED ITS WORTH TO THOUSANDS OF WALKERS AND OUT-OF-DOORS ADVEN TURERS. MAKE SURE YOU, TOO, HAVE THE BEST OF GEAR. From- PADDY PALLIN Py. ltd. 201 CASTLEREAGH STREET, SYDNEY - Phone BM 2685 Ask for our Latest Price List Get your copy of "Bushwalking - --- and Camping," by Paddy Pallin -5/6 posted --------------------------------------------------· CWalk A JOURNAL OF THE MELBOURNE BUSHW ALKERS NUMBER FOURTEEN 1963 CONTENTS: * BY THE PEOPLE 'l ... -

Sydney Gateway

Sydney Gateway State Significant Infrastructure Scoping Report BLANK PAGE Sydney Gateway road project State Significant Infrastructure Scoping Report Roads and Maritime Services | November 2018 Prepared by the Gateway to Sydney Joint Venture (WSP Australia Pty Limited and GHD Pty Ltd) and Roads and Maritime Services Copyright: The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of NSW Roads and Maritime Services. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of NSW Roads and Maritime Services constitutes an infringement of copyright. Document controls Approval and authorisation Title Sydney Gateway road project State Significant Infrastructure Scoping Report Accepted on behalf of NSW Fraser Leishman, Roads and Maritime Services Project Director, Sydney Gateway by: Signed: Dated: 16-11-18 Executive summary Overview Sydney Gateway is part of a NSW and Australian Government initiative to improve road and freight rail transport through the important economic gateways of Sydney Airport and Port Botany. Sydney Gateway is comprised of two projects: · Sydney Gateway road project (the project) · Port Botany Rail Duplication – to duplicate a three kilometre section of the Port Botany freight rail line. NSW Roads and Maritime Services (Roads and Maritime) and Sydney Airport Corporation Limited propose to build the Sydney Gateway road project, to provide new direct high capacity road connections linking the Sydney motorway network with Sydney Kingsford Smith Airport (Sydney Airport). The location of Sydney Gateway, including the project, is shown on Figure 1.1. Roads and Maritime has formed the view that the project is likely to significantly affect the environment. On this basis, the project is declared to be State significant infrastructure under Division 5.2 of the NSW Environmental Planning & Assessment Act 1979 (EP&A Act), and needs approval from the NSW Minister for Planning. -

Assessing Estuary Ecosystem Health: Sampling, Data Analysis and Reporting Protocols

Assessing estuary ecosystem health: Sampling, data analysis and reporting protocols NSW Natural Resources Monitoring, Evaluation and Reporting Program Cover image: Meroo Lake, Meroo National Park/M Jarman OEH © 2013 State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage With the exception of photographs, the State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. The Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH) has compiled this publication in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. OEH shall not be liable for any damage which may occur to any person or organisation taking action or not on the basis of this publication. Readers should seek appropriate advice when applying the information to their specific needs. Published by: Office of Environment and Heritage 59 Goulburn Street, Sydney NSW 2000 PO Box A290, Sydney South NSW Phone: (02) 9995 5000 (switchboard) Phone: 131 555 (environment information and publications requests) Phone: 1300 361 967 (national parks, general environmental inquiries and publications requests) Fax: (02) 9995 5999 TTY users: phone 133 677, then ask for 131 555 Speak and listen users: phone 1300 555 727, -

Historical Riparian Vegetation Changes in Eastern NSW

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Science, Medicine & Health - Honours Theses University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2016 Historical Riparian Vegetation Changes in Eastern NSW Angus Skorulis Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/thsci University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Skorulis, Angus, Historical Riparian Vegetation Changes in Eastern NSW, BSci Hons, School of Earth & Environmental Science, University of Wollongong, 2016. https://ro.uow.edu.au/thsci/120 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. -

Sydneyœsouth Coast Region Irrigation Profile

SydneyœSouth Coast Region Irrigation Profile compiled by Meredith Hope and John O‘Connor, for the W ater Use Efficiency Advisory Unit, Dubbo The Water Use Efficiency Advisory Unit is a NSW Government joint initiative between NSW Agriculture and the Department of Sustainable Natural Resources. © The State of New South Wales NSW Agriculture (2001) This Irrigation Profile is one of a series for New South Wales catchments and regions. It was written and compiled by Meredith Hope, NSW Agriculture, for the Water Use Efficiency Advisory Unit, 37 Carrington Street, Dubbo, NSW, 2830, with assistance from John O'Connor (Resource Management Officer, Sydney-South Coast, NSW Agriculture). ISBN 0 7347 1335 5 (individual) ISBN 0 7347 1372 X (series) (This reprint issued May 2003. First issued on the Internet in October 2001. Issued a second time on cd and on the Internet in November 2003) Disclaimer: This document has been prepared by the author for NSW Agriculture, for and on behalf of the State of New South Wales, in good faith on the basis of available information. While the information contained in the document has been formulated with all due care, the users of the document must obtain their own advice and conduct their own investigations and assessments of any proposals they are considering, in the light of their own individual circumstances. The document is made available on the understanding that the State of New South Wales, the author and the publisher, their respective servants and agents accept no responsibility for any person, acting on, or relying on, or upon any opinion, advice, representation, statement of information whether expressed or implied in the document, and disclaim all liability for any loss, damage, cost or expense incurred or arising by reason of any person using or relying on the information contained in the document or by reason of any error, omission, defect or mis-statement (whether such error, omission or mis-statement is caused by or arises from negligence, lack of care or otherwise). -

NPWS Annual Report 2000-2001 (PDF

Annual report 2000-2001 NPWS mission NSW national Parks & Wildlife service 2 Contents Director-General’s foreword 6 3 Conservation management 43 Working with Aboriginal communities 44 Overview 8 Joint management of national parks 44 Mission statement 8 Performance and future directions 45 Role and functions 8 Outside the reserve system 46 Partners and stakeholders 8 Voluntary conservation agreements 46 Legal basis 8 Biodiversity conservation programs 46 Organisational structure 8 Wildlife management 47 Lands managed for conservation 8 Performance and future directions 48 Organisational chart 10 Ecologically sustainable management Key result areas 12 of NPWS operations 48 Threatened species conservation 48 1 Conservation assessment 13 Southern Regional Forest Agreement 49 NSW Biodiversity Strategy 14 Caring for the environment 49 Regional assessments 14 Waste management 49 Wilderness assessment 16 Performance and future directions 50 Assessment of vacant Crown land in north-east New South Wales 19 Managing our built assets 51 Vegetation surveys and mapping 19 Buildings 51 Wetland and river system survey and research 21 Roads and other access 51 Native fauna surveys and research 22 Other park infrastructure 52 Threat management research 26 Thredbo Coronial Inquiry 53 Cultural heritage research 28 Performance and future directions 54 Conservation research and assessment tools 29 Managing site use in protected areas 54 Performance and future directions 30 Performance and future directions 54 Contributing to communities 55 2 Conservation planning