A Pervasive Yet Idle Sentiment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Curioos Incident: Scottish Party Competition Since

committed without difficulty. Some of the central ideas in the new Government's manifesto were bound to hurt Scotland particularly. Cutting public expenditure would take cash away from the industries and public services on which Scotland was disproportionately dependent. "Improving the pro THE CURIOOS INCIDENT: ductivity" of the nationalised industries might easily lead to con siderable unemployment in Scotland. Cuts in regional employment SCOTTISH PARTY COMPETITION SINCE 1979 Henry Drucker grants, on which Scotland was dependent would hurt too. Only a curso Department of Politics ry glance at the history of recent Conservative governments lacking University of Edinburgh a Scottish plurality showed the danger. The Macmillan-Home adminis "Is there any point to which you would wish to draw my attention?" tration was harried to derision toward the end of its term by the "To the Curious incident of the dog in the night-time". Scottish Parliamentary Labour team led by Willie Ross. The Heath "The dog did nothing in the night-time". "That was the curious incident", remarked Sherlock Holmes. government had been forced into one of its most humiliating voltes The Conservative government formed after the May 1979 general face over the collapse of Upper Clyde Shipbuilders. election lacked a parliamentary majority in Scotland. For the seventh And the new Government had more than Labour to fear. If the election in succession the Scottish people had returned a Labour maj official Opposition failed to make the running against her, then the ority. The government owed its parliamentary strength to its victor SNP was only too anxious to do so. -

Members 1979-2010

Members 1979-2010 RESEARCH PAPER 10/33 28 April 2010 This Research Paper provides a complete list of all Members who have served in the House of Commons since the general election of 1979 to the dissolution of Parliament on 12 April 2010. The Paper also provides basic biographical and parliamentary data. The Library and House of Commons Information Office are frequently asked for such information and this Paper is based on the data we collate from published sources to assist us in responding. This Paper replaces an earlier version, Research Paper 09/31. Oonagh Gay Richard Cracknell Jeremy Hardacre Jean Fessey Recent Research Papers 10/22 Crime and Security Bill: Committee Stage Report 03.03.10 10/23 Third Parties (Rights Against Insurers) Bill [HL] [Bill 79 of 2009-10] 08.03.10 10/24 Local Authorities (Overview and Scrutiny) Bill: Committee Stage Report 08.03.10 10/25 Northern Ireland Assembly Members Bill [HL] [Bill 75 of 2009-10] 09.03.10 10/26 Debt Relief (Developing Countries) Bill: Committee Stage Report 11.03.10 10/27 Unemployment by Constituency, February 2010 17.03.10 10/28 Transport Policy in 2010: a rough guide 19.03.10 10/29 Direct taxes: rates and allowances 2010/11 26.03.10 10/30 Digital Economy Bill [HL] [Bill 89 of 2009-10] 29.03.10 10/31 Economic Indicators, April 2010 06.04.10 10/32 Claimant Count Unemployment in the new (2010) Parliamentary 12.04.10 Constituencies Research Paper 10/33 Contributing Authors: Oonagh Gay, Parliament and Constitution Centre Richard Cracknell, Social and General Statistics Section Jeremy Hardacre, Statistics Resources Unit Jean Fessey, House of Commons Information Office This information is provided to Members of Parliament in support of their parliamentary duties and is not intended to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. -

The 2011 Scottish General Election: Implications for Scotland and for Britain Written by Danus G

The 2011 Scottish General Election: Implications for Scotland and for Britain Written by Danus G. M. Skene This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. The 2011 Scottish General Election: Implications for Scotland and for Britain https://www.e-ir.info/2011/05/19/the-5-may-2011-scottish-general-election-implications-for-scotland-and-for-britain/ DANUS G. M. SKENE, MAY 19 2011 “A Political Tsunami” Once upon a time, at the UK General Election of February 1974, I was the Labour candidate in a seat called at that time Kinross & West Perthshire. The sitting MP was Sir Alec Douglas Home. A few years before, he had been British Prime Minister, and at the time of this election was Conservative Foreign Secretary. It was one of the weakest two or three seats in Scotland for Labour, and I would be doing very well to get 10% of the vote. The late Willie Hamilton, Labour MP and politician, told me before the election that he refused to wish me luck. If I won Kinross for Labour, we would be living in a one party state, and he didn’t want that. As it was, I came last of 4 candidates with 9.9% of the vote. Alec Home won with 53%. On 5 May, Scotland came close to becoming a one-party state. It is alleged that when First Minister and Scottish National Party (SNP) leader, Alex Salmond, was told that the SNP had won Clydebank – solidly Labour for 90 years and not a Nationalist target in their wildest dreams – all he could come out with was an unprintable expletive, some sort of updated version of Willie Hamilton’s message to me 37 years before. -

148868291.Pdf

t· •.•·•.· .•·....... ·.· l.. ' "'. R ,I I CONTENTS The week 3 Green light for European elections . 3 Uproar over margarine tax . 8 The acceptable face of competition 11 Drought and the cost of living 14 Community research has a future (but no bets on JET yet) . 15 Agreement with Canada welcomed . 16 Joint meeting with Cou~cil of Europe . 18 Helping the hungry . 24 Question Time 25 Summary of the week . 28 References . 33 Abbreviations . 34 Postscript - European elections : the decision and the act signed by the Nine Foreign Ministers in Brussels on September 20th. 34 -1- SESSION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 1976- 1977 Sittings held in Luxembourg Monday 13 September to Friday 17 September 1976 The Week The good news this week was Laurens Jan Brinkhorst's announcement that the Nine Foreign Ministers would sign a decision (spelling out a date) and and act (spelling out a commitment) on European elections at their meeting in Brussels on September 20th. This still leaves open the question of ratification (where necessacy) by national parliaments and that of legislating to organize the elections themselves, hopefully for May or June 1978. But there is some optimism that all this can be done in time. The other main issues arising this week were research, the drought and its aftermath, the proposed vegetable oils tax, competition and what can be learned from the Seve so disaster. Green light for European elections Laurens Jan Brinkhorst, Dutch Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs and current President of the Community's decision-taking Council of Ministers, told the European Parliament on September 15th that the Council would take the final decision on European elections when it met in Brussels on September 20th. -

SLR I10 May-Jun 02.Indd

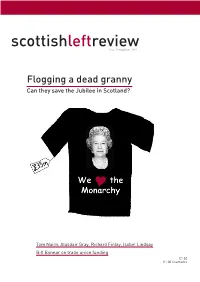

scottishleftreview Issue 10 May/June 2001 Flogging a dead granny Can they save the Jubilee in Scotland? Tom Nairn, Alasdair Gray, Richard Finlay, Isobel Lindsay Bill Bonnar on trade union funding £1.50 £1.00 Claimants comment scottishleftreview Issue 10 May/June 2002 full-page advert in a tabloid newspaper costs tens A journal of the left in Scotland brought about since the formation of the A of thousands of pounds. You would pay thousands Scottish Parliament in July 1999 of pounds a second for television advertising. So do the Contents maths for yourself – we have just seen one of the most expensive advertising campaigns in history. In the space Comment ................................................... 2 of a week or so, we have seen a campaign run which, if any of us was to try to replicate it, would have cost us hundreds The party is over ........................................ 4 of millions of pounds. And what have we been urged to Tom Nairn buy? On sale was a vision of a deeply conservative Britain of subjects of a monarch and her dysfunctional family. We Article 2...................................................... 6 were sold a Jubilee which they were petrified was going Richard Finlay to be stillborn. And as we all know, it worked a treat; en Calling their bluff....................................... 8 masse, Britain was persuaded to come out in misty-eyed support for one of its most reactionary symbols. Isobel Lindsay The dead monkey society ........................ 10 Or so we have been led to believe. Even the left-wing commentators in our more thoughtful media have been Mike Small scrambling to try to make sense of the groundswell of Only queens and refugees ...................... -

House of Lords Official Report

Vol. 736 Monday No. 291 23 April 2012 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) HOUSE OF LORDS OFFICIAL REPORT ORDER OF BUSINESS Deaths of Members Questions Finance: Equity Markets Social Tourism Immigration: Eurostar Workers’ Memorial Day House of Lords Reform Statement Business of the House Motion on Standing Orders Canterbury City Council Bill Leeds City Council Bill Nottingham City Council Bill Reading Borough Council Bill Motions to Resolve City of London (Various Powers) Bill [HL] City of Westminster Bill [HL] Transport for London Bill [HL] Motions to Resolve Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Bill Commons Reasons and Amendments Grand Committee Health: Pancreatic Cancer Housing: Flats Armed Forces: Personnel Questions for Short Debate Written Statements Written Answers For column numbers see back page £3·50 Lords wishing to be supplied with these Daily Reports should give notice to this effect to the Printed Paper Office. The bound volumes also will be sent to those Peers who similarly notify their wish to receive them. No proofs of Daily Reports are provided. Corrections for the bound volume which Lords wish to suggest to the report of their speeches should be clearly indicated in a copy of the Daily Report, which, with the column numbers concerned shown on the front cover, should be sent to the Editor of Debates, House of Lords, within 14 days of the date of the Daily Report. This issue of the Official Report is also available on the Internet at www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201212/ldhansrd/index/120423.html PRICES AND SUBSCRIPTION RATES DAILY PARTS Single copies: Commons, £5; Lords £3·50 Annual subscriptions: Commons, £865; Lords £525 WEEKLY HANSARD Single copies: Commons, £12; Lords £6 Annual subscriptions: Commons, £440; Lords £255 Index: Annual subscriptions: Commons, £125; Lords, £65. -

Download (2MB)

Gibbs, Ewan (2016) Deindustrialisation and industrial communities: the Lanarkshire coalfields c.1947-1983. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/7751/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Deindustrialisation and Industrial Communities: The Lanarkshire Coalfields c.1947-1983 Ewan Gibbs, MSc, M.A. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Ph.D in Economic and Social History School of Social and Political Sciences College of Social Sciences University of Glasgow November 2016 Abstract Deindustrialisation and Industrial Communities: The Lanarkshire Coalfields c.1947-1983 This thesis examines deindustrialisation, the declining contribution of industrial activities to economic output and employment, in Lanarkshire, Scotland’s largest coalfield between the early nineteenth and mid-twentieth century. It focuses on contraction between the National Coal Board’s (NCB) vesting in 1947 and the closure of Lanarkshire’s last colliery, Cardowan, in 1983. Deindustrialisation was not the natural outcome of either market forces or geological exhaustion. Colliery closures and falling coal employment were the result of policy-makers’ decisions. -

Book of Abstracts

Book of Abstracts Published by Society for Academic Primary Care DOI reference: 10.37361/asm.2020.1.1 DOI LINK: https://sapc.ac.uk/doi/10.37361/asm.2020.1.1 Abstracts on-line: https://sapc.ac.uk/conference/2020/abstracts Copyright belongs to the authors of the individual abstracts under the creative commons licence The abstracts have been published as submitted without further editing 1 Foreword 2020 will forever be remembered as the year of the COVID-19 pandemic. For the first time since 1972, the 49th Annual Scientific Meeting of the SAPC, due to be held in Leeds in July 2020, could not take place. The cancellation occurred after the submission deadline for abstracts, and, as there was no capacity for a ‘virtual’ meeting, these abstracts could not be presented. We thank all of the authors, from around the world, for their submissions, which were, as ever, of high quality, importance, and impact, reflecting the state of our discipline. We have great pleasure in publishing the abstracts in this document. A total of 281 abstracts were submitted, 205 for consideration as ‘long orals’, and 76 as ‘short orals’. A couple of ‘technical’ points to note: . The theme of the meeting was ‘Living and Dying Well’. This has become more poignant as the events of 2020 sadly unfold. They are published ‘as submitted’ with no edits or updates from authors . There has been no selection of abstracts – all are included, except those where authors have declined the option of publication The ASM in Leeds has been rescheduled for 30th June – 2nd July 2021, and we look forward to hosting a successful meeting. -

Proposals for the Reform of the Composition and Powers of the House of Lords, 1968–1998

Proposals for the Reform of the Composition and Powers of the House of Lords, 1968–1998 This Library Note sets out in summary form major proposals since 1968 for reform of the composition and powers of the House of Lords. Hugo Deadman 14 July 1998 LLN 1998/004 House of Lords Library Notes are compiled for the benefit of Members of Parliament and their personal staff. Authors are available to discuss the contents of the Notes with the Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public. Any comments on Library Notes should be sent to the Head of Research Services, House of Lords Library, London SW1A 0PW or emailed to [email protected]. Introduction This Library Note sets out in summary form major proposals which have been made since 1968 for reform of the composition and powers of the House of Lords. It updates an earlier Library Note (LLN 1996/003) on this subject and covers proposals made by the end of June 1998. To avoid excessive length, the Note does not examine the reactions to each proposal in detail. 1. Parliament (No 2) Bill 1968–691 1.1 Events leading to the introduction of the Bill In its General Election manifesto of 1966, the Labour Party promised to safeguard measures approved in the House of Commons from frustration by delay or defeat in the House of Lords. This pledge was repeated in the Queen‘s Speech of 31 October 1967, which also stated that the Government would be willing to enter into consultations appropriate to a constitutional change of such importance. -

Coal Country the Meaning and Memory of Deindustrialization in Postwar Scotland

Downloaded from the Humanities Digital Library http://www.humanities-digital-library.org Open Access books made available by the School of Advanced Study, University of London Press ***** Publication details: Coal Country: the Meaning and Memory of Deindustrialization in Postwar Scotland By Ewan Gibbs https://humanities-digital-library.org/index.php/hdl/catalog/book/ coal-country DOI: 10.14296/321.9781912702589 ***** This edition published in 2021 by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PRESS SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU, United Kingdom ISBN 978-1-912702-58-9 (PDF edition) This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses Coal Country The Meaning and Memory of Deindustrialization in Postwar Scotland EWAN GIBBS Coal Country The Meaning and Memory of Deindustrialization in Postwar Scotland New Historical Perspectives is a book series for early career scholars within the UK and the Republic of Ireland. Books in the series are overseen by an expert editorial board to ensure the highest standards of peer-reviewed scholarship. Commissioning and editing is undertaken by the Royal Historical Society, and the series is published under the imprint of the Institute of Historical Research by the University of London Press. The series is supported by the Economic History Society and the Past and Present Society. Series co-editors: Heather -

Members of the House of Commons Since 1979

BRIEFING PAPER Number CBP 8256, 13 March 2018 Members of the House of By Chris Watson Commons since 1979 Mark Fawcett Contents: 1. Background 2. All Members of the House of Commons since the 1979 General Election www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary ii Members of the House of Commons since 1979 Contents Summary iii Glossary iv 1. Background vii 1.1 Gender vii 1.2 Age viii 1.3 Ethnicity ix 1.4 Occupation x 2. All Members of the House of Commons since the 1979 General Election xi A 1 B 8 C 33 D 53 E 65 F 70 G 80 H 93 I 115 J 116 K 124 L 130 M 142 N 171 O 174 P 178 Q 189 R 189 S 201 T 222 U 231 V 232 W 233 Y 250 Z 251 Contributing Authors: Oliver Hawkins, Richard Cracknell, Lucinda Maer, Richard Kelly, Mark Sandford, Neil Johnston, Hazel Armstrong, Sarah Priddy, Paul Little Cover page image copyright : Attributed to: Theresa May's first PMQs as Prime Minister by UK Parliament. Licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0 / image cropped. iii Commons Library Briefing, 13 March 2018 Summary Since the 1979 General Election, there have been 2,128 people elected to the House of Commons. Of these, 403 have been women and 1,725 have been men. This publication lists all Members of the House of Commons starting from the 1979 General Election which took place on the 3 May. It is a new edition of our 2010 publication. -

The Labour Party and British Republicanism Kenneth O

The Labour Party and British Republicanism Kenneth O. MORGAN The famous detective, Sherlock Holmes, once solved a case by referring to “the dog that did not bark.” In the past 250 years of British history, republicanism is another dog that did not bark. This is particularly true of supposedly our most radical major political party, the Labour Party. Over the monarchy, as over constitutional matters generally, Labour’s instincts have been conservative. Even after 1997, when the party, led by Lord Irvine, has indeed embarked upon major constitutional reforms—devolution for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland; an elected mayor of London; the abolition of nearly all hereditary peers; incorporation of the European convention of human rights into British law; a Freedom of Information Act—the monarchy has remained untouched. Here the hereditary principle, rejected for the House of Lords, remains sacrosanct. All Labour prime ministers, Ramsay MacDonald (1924, 1929-31), Clement Attlee (1945-51), Harold Wilson (1964-70, 1974-6), James Callaghan (1976-9) and, up to a point, Tony Blair have remained deferential towards their King or Queen and their entourage. The present Queen Elizabeth II had by far her worst relationship with a Conservative premier, Margaret Thatcher who did not share the Queen’s enthusiasm for a multiracial Commonwealth. Labour has thrown up only a few incidental protests, such as the “anti-jubilee” New Statesman in the summer of 1977 (in which I took part), described by the Daily Mail of the time as showing “the termites of the Left coming out of the woodwork!”1 In the past twenty years, the British monarchy has certainly weakened.