3 COMMON TRAPS Four Talk Styles to Avoid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Human Aura

The Human Aura Manual compiled by Dr Gaynor du Perez Copyright © 2016 by Gaynor du Perez All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without the written permission of the author. INTRODUCTION Look beneath the surface of the world – the world that includes your clothes, skin, material possessions and everything you can see - and you will discover a universe of swirling and subtle energies. These are the energies that underlie physical reality – they form you and everything you see. Many scientific studies have been done on subtle energies, as well as the human subtle energy system, in an attempt to verify and understand how everything fits together. What is interesting to note is that even though the subtle energy systems on the earth have been verified scientifically as existing and even given names, scientists are only able to explain how some of them work. Even though we do not fully comprehend the enormity and absolute amazingness of these energies, they form an integral part of life as we know it. These various energy systems still exist regardless of whether you “believe in them” or not (unlike Santa Claus). You can liken them to micro-organisms that were unable to be seen before the invention of the microscope – they couldn’t be seen, but they killed people anyway. We, and everything in the universe, is made of energy, which can be defined most simply as “information that vibrates”. What’s more interesting is that everything vibrates at its own unique frequency / speed, for example, a brain cell vibrates differently than a hair cell, and similar organisms vibrate in similar ways, but retain a slightly different frequency than the other. -

Where Currents Connect

The Current GAHANNA PARKS & RECREATION ACTIVITY GUIDE Winter 2019-2020 Parks & Recreation WorkWhere in Gahanna? Receive the Currents Resident Discount Rate (RDR) Connect 1 Civic Leaders City of Gahanna Advisory Committees TABLE OF CONTENTS Mayor Tom Kneeland Parks & Recreation Board City Attorney Shane W. Ewald Meetings are held at 7pm on the second Civic Leaders 2 Wednesday of each month at City Hall Gahanna City Council unless otherwise noted. All meetings are Rental Facilities 3 Contact: [email protected] open to the public. Ward 1: Stephen A. Renner, Vice President Jan Ross, Chair Ward 2: Michael Schnetzer Andrew Piccolantonio, Vice Chair Aquatics 4 Ward 3: Brian Larick Cynthia Franzmann Ward 4: Jamie Leeseberg Chrissy Kaminski Active Seniors At Large: Karen J. Angelou Eric Miller 5 Nancy McGregor Daphne Moehring Brian Metzbower, President Ken Shepherd Parks Information 10 Parks & Recreation Staff Landscape Board Contact: [email protected] The Landscape Board meetings are listed online at Jeffrey Barr, Director Ohio Herb Center 11 www.gahanna.gov. Meetings are held at City Hall Stephania Bernard-Ferrell, Deputy Director unless otherwise noted. Alan Little, Parks & Facilities Superintendent All meetings are open to the public. Golf Course 12 Brian Gill, Recreation Superintendent Jane Allinder, Chair Jim Ferguson, Parks Foreman Melissa Hyde, Vice Chair Zac Guthrie, Parks & Community Services Supervisor Outdoor Experiences 13 Kevin Dengel Joe Hebdo, Golf Course Supervisor Mark DiGiando Curt Martin, Facilities Coordinator Matt Winger Camp Experiences 14 Sarah Mill, Recreation Supervisor Julie Predieri, City Forester Pam Ripley, Office Coordinator Arts & Education 15 Marty White, Facilities Foreman Recreation & Sports 16 How to register 19 Volunteer Advisory Committees The Parks & Recreation Board created the following advisory committees to assist the Department of Parks & Recreation with facilitating, planning, promoting and implementing projects with the assistance of volunteer residents. -

130868257991690000 Lagniap

2 | LAGNIAPPE | September 17, 2015 - September 23, 2015 LAGNIAPPE ••••••••••••••••••••••••••• WEEKLY SEPTEMBER 17, 2015 – S EPTEMBER 23, 2015 | www.lagniappemobile.com Ashley Trice BAY BRIEFS Co-publisher/Editor Federal prosecutors have secured an [email protected] 11th guilty plea in a long bid-rigging Rob Holbert scheme based in home foreclosures. Co-publisher/Managing Editor 5 [email protected] COMMENTARY Steve Hall Marketing/Sales Director The Trice “behind closed doors” [email protected] secrets revealed. Gabriel Tynes Assistant Managing Editor 12 [email protected] Dale Liesch BUSINESS Reporter Greer’s is promoting its seventh year [email protected] of participating in the “Apples for Jason Johnson Students” initiative. Reporter 16 [email protected] Eric Mann Reporter CUISINE [email protected] A highly anticipated Kevin Lee CONTENTS visit to The Melting Associate Editor/Arts Editor Pot in Mobile proved [email protected] disappointing with Andy MacDonald Cuisine Editor lackluster service and [email protected] forgettable flavors. Stephen Centanni Music Editor [email protected] J. Mark Bryant Sports Writer 18 [email protected] 18 Stephanie Poe Copy Editor COVER Daniel Anderson Mobilian Frank Bolton Chief Photographer III has organized fellow [email protected] veterans from atomic Laura Rasmussen Art Director test site cleanup www.laurarasmussen.com duties to share their Brooke Mathis experiences and Advertising Sales Executive resulting health issues [email protected] and fight for necessary Beth Williams Advertising Sales Executive treatment. [email protected] 2424 Misty Groh Advertising Sales Executive [email protected] ARTS Kelly Woods The University of South Alabama’s Advertising Sales Executive Archaeology Museum reaches out [email protected] to the curious with 12,000 years of Melissa Schwarz 26 history. -

Undergraduate Review, Vol. 8, 2011/2012

Undergraduate Review Volume 8 Article 1 2012 Undergraduate Review, Vol. 8, 2011/2012 Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/undergrad_rev Recommended Citation Bridgewater State University. (2012). Undergraduate Review, 8. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/undergrad_rev/vol8/iss1/1 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Copyright © 2012 volume VIII 2011-2012 The Undergraduate Review A JOURNAL OF undergraduate research AND creative work Great Wall of China Anderson, Andrade, Ashley, Carreiro, DeCastro, DeMont, George, Graham, Harkins, Johnston, Joubert, Larracey, MacDonald, Manning, Medina, Menz, Mulcahy, Ranero, Rober, Sauber, Spooner, Thompson, Tully, Woofenden BridgEwatEr StatE UNiVErSitY 2012 • thE UNdErgradUatE ReviEw • 159 Letter from the editor a great amount of vigor and teamwork, and “All great changes are preceded by chaos.” -Deepak Chopra ’m not comfortable with change. It causes me great angst and, on occasion, to hyperventilate. In fact, if my life were to flash before my eyes, many moments would include illegal U-turns, the sound of squealing brakes and me huffing and puffing into brown paper bags only to be catapulted Iforward, nonetheless, into varying degrees of discomfort and consequence. And, yet, I have survived each and every occurrence. Not always with grace, not always unscathed, or with the intended outcome; but always with growth, emerging shiny and new with a new-found purpose and vision: just like this year’s volume of The Undergraduate Review. Last fall, our review committee met to reassess the journal’s publication process. It was determined that the journal was in need of an overhaul. -

Napoleon and Tabitha Dumo Television

Napoleon and Tabitha Dumo Television: Sonic Lip Sync Battle Creative Directors Amazingness Creative Producers MTV ABC Holiday Special Creative Producers ABC Macy's Thanksgiving Day Choreographers NBC Parade White Hot Holidays Co-Executive Producers FOX Sunday Night Football Co. Exec Producers NBC World of Dance Co. Exec. Produers NBC Lip Sync Battle Jr Co. Exec. Producers Spike TV / Nikelodeon America's Best Dance Crew Co-Executive Producers MTV Season 8 Mobbed Co-Executive Producers/Hosts FOX / Brainstorm TV Sing Your Face Off Performance Producers ABC American Idol Season 15 w/ Creative Directors FOX Jennifer Lopez American Idol Season 14 w/ Creative Directors FOX Jennifer Lopez American Idol Season 11 Coordinating Producers & FOX Supervising Choreographers American Idol Season 10 Choreographers FOX Homeward Bound Telethon / Directors/Choreographers Military Channel 2013 Veteran's Day Special Live with Kelly and Michael Creative Sean Kingston/Epic Directors/Choreographers So You Think You can Dance Choreographers FOX Season 1-14 (2 EMMY WINS) So You Think You Can Dance Creative Directors FOX w/Jennifer Lopez, Natasha Beddingfield, Enrique Iglesia Lopez Tonight w/ Cirque Du Creative Directors TBS Soleil "Mystere" America's Got Talent w/ Creative Directors NBC/SyCo Entertainment Cirque Du Soleil "KA" America's Got Talent w/ Creative Directors NBC/SyCo Entertainment Cirque Du Soleil "LOVE" Dancing with the Stars w/ Creative Directors ABC Cirque Du Soleil "Viva Elvis" America's Best Dance Crew Supervising Choreographers MTV Season 1-7 Hunan Television New Year's Choreographers Hunan Television China Eve 2010 New Year's Rockin Eve Choreographers Jennifer Lopez / Times Square /ABC Carrie Underwood TV Special Choreographers ABC / Sony Music Rock the Reception Choreographers/Hosts Times Square/ABC The Ellen Degeneres Show Choreographers FOX Celine Dion Special Host/Choreographers TLC One on One Supervising Choreographers MTV Becoming Contributing Choreographers CBS/Ken Ehrlich Prod. -

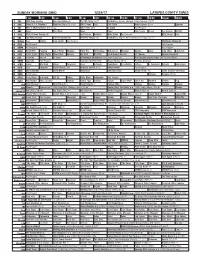

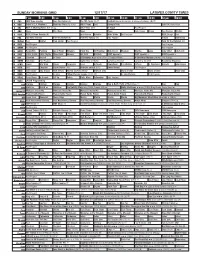

Sunday Morning Grid 12/24/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/24/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Los Angeles Chargers at New York Jets. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid PGA TOUR Action Sports (N) Å Spartan 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Los Angeles Rams at Tennessee Titans. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Christmas Miracle at 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Martha Jazzy Julia Child Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ 53rd Annual Wassail St. Thomas Holiday Handbells 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch A Firehouse Christmas (2016) Anna Hutchison. The Spruces and the Pines (2017) Jonna Walsh. 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Grandma Got Run Over Netas Divinas (TV14) Premios Juventud 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

2021 GSOH Council VRG.Pdf

2020-2021 1 Sept. 1, 2020 I’m excited to welcome you as a volunteer for the Girl Scouts of Ohio’s Heartland Council. You have embarked on the wonderful adventure of helping build girls of courage, confidence and character. We couldn’t do it without you and for that I am grateful! Together, we are creating a space for girls to feel comfortable to be themselves, to find their voices and to flourish as leaders. Please know that we are dedicated to providing you the tools needed for our girls to succeed. The “Volunteer Resource Guide” (VRG) will serve as a reference in helping make your volunteer role a rewarding experience throughout this membership year. As you set off to lead and inspire, I encourage you to share your stories and motivate others to join in the mission of Girl Scouts. And while our delivery method of meetings and programming may be a bit different this year, I invite you to enjoy creating lifelong memories with our girls and other dedicated members of Girl Scouts. Together, we can make the world a better place! Yours in Girl Scouting, Tammy H. Wharton President & Chief Executive Officer Girl Scouts of Ohio’s Heartland 2 Contents TROOP CAMP ................................................................ 26 MANAGING GIRLS FINANCES ................................... 27 INTRODUCTION ......................................................... 4 UNDERSTANDING FINANCIAL ABILITY BY GRADE LEVEL .......... 27 GIRL SCOUTS OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA/GSUSA .....4 BANK ACCOUNTS ........................................................... 28 GIRL SCOUTS OF OHIO’S HEARTLAND/GSOH ........................5 TROOP FINANCE OPERATIONS – WHAT SHOULD I KNOW? ..... 31 GIRL SCOUT VOLUNTEERS .......................................... 7 TROOP AND SERVICE UNIT FINANCE REPORTS ..................... 33 DISCREPANCIES/MISMANAGEMENT OF FUNDS ................... -

SEPTEMBER 6, 2021 Delmarracing.Com

21DLM002_SummerProgramCover_ Trim_4.125x8.625__Bleed_4.375x8.875 HOME OF THE 2021 BREEDERS’ CUP JULY 16 - SEPTEMBER 6, 2021 DelMarRacing.com 21DLM002_Summer Program Cover.indd 1 6/10/21 2:00 PM DEL MAR THOROUGHBRED CLUB Racing 31 Days • July 16 - September 6, 2021 Day 15 • Thursday August 12, 2021 First Post 2:00 p.m. These are the moments that make history. Where the Turf Meets the Surf Keeneland sales graduates have won Del Mar racetrack opened its doors (and its betting six editions of the Pacific Classic over windows) on July 3, 1937. Since then it’s become West the last decade. Coast racing’s summer destination where avid fans and newcomers to the sport enjoy the beauty and excitement of Thoroughbred racing in a gorgeous seaside setting. CHANGES AND RESULTS Courtesy of Equibase Del Mar Changes, live odds, results and race replays at your ngertips. Dmtc.com/app for iPhone or Android or visit dmtc.com NOTICE TO CUSTOMERS Federal law requires that customers for certain transactions be identi ed by name, address, government-issued identi cation and other relevant information. Therefore, customers may be asked to provide information and identi cation to comply with the law. www.msb.gov PROGRAM ERRORS Every effort is made to avoid mistakes in the of cial program, but Del Mar Thoroughbred Club assumes no liability to anyone for Beholder errors that may occur. 2016 Pacific CHECK YOUR TICKET AND MONIES BEFORE Classic S. (G1) CONFIRMING WAGER. MANAGEMENT ASSUMES NO RESPONSIBLITY FOR TRANSACTIONS NOT COMPLETED WHEN WAGERING CLOSES. POST TIMES Post times for today’s on-track and imported races appear on the following page. -

Black Female School Counselors' Experiences

INTERCHANGEABLE OPPRESSION: BLACK FEMALE SCHOOL COUNSELORS’ EXPERIENCES WITH BLACK ADOLESCENT GIRLS IN URBAN MIDDLE SCHOOLS Sonya June Hicks Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Education, Indiana University August 2021 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty of Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Tambra Jackson Ph.D., Chair ______________________________________ Chalmer Thompson Ph.D. May 26, 2021 ______________________________________ Sha’Kema Blackmon Ph.D. ______________________________________ Crystal Morton Ph.D. ii © 2021 Sonya June Hicks iii DEDICATION This manuscript is dedicated to the Black female educators who strive daily to nurture, protect, and inspire Black girls to achieve, both individually and collectively. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I first thank God, and my Lord Jesus Christ for granting me the mental and physical strength to complete this project. To my family. First, my dear, loving, and amazing husband. I thank you for you for providing me unending support, encouragement, inspiration, and love throughout this PhD journey. I love you John…We did this together. Next, to my children. You inspire me to be the woman God wants me to be. You give me life, and you are Gifts from God that I am ever thankful for. Keep making me proud and be the individuals God wants you to be. I love you, Jillian (Javonte), and Matthew. To my loving parents. I thank my parents “James” Herman Bond and Ola June Bond (Jones) for giving me life and instilling in me God’s principles of love and faithfulness. -

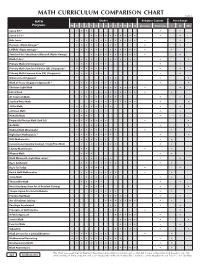

Math Curriculum Comparison Chart

MATH CURRICULUM COMPARISON CHART ©2018 MATH Grades Religious Content Price Range Programs PK K 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Christian N/Secular $ $$ $$$ Saxon K-3 * • • • • • • Saxon 3-12 * • • • • • • • • • • • • Bob Jones • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Horizons (Alpha Omega) * • • • • • • • • • • • LIFEPAC (Alpha Omega) * • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Switched-On Schoolhouse/Monarch (Alpha Omega) • • • • • • • • • • • • Math•U•See * • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Primary Math (US) (Singapore) * • • • • • • • • • Primary Math Standards Edition (SE) (Singapore) * • • • • • • • • • Primary Math Common Core (CC) (Singapore) • • • • • • • • Dimensions (Singapore) • • • • • Math in Focus (Singapore Approach) * • • • • • • • • • • • Christian Light Math • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Life of Fred • • • • • • • • • • • • • • A+ Tutorsoft Math • • • • • • • • • • • Starline Press Math • • • • • • • • • • • • ShillerMath • • • • • • • • • • • enVision Math • • • • • • • • • McRuffy Math • • • • • • Purposeful Design Math (2nd Ed.) • • • • • • • • • Go Math • • • • • • • • • Making Math Meaningful • • • • • • • • • • • RightStart Mathematics * • • • • • • • • • • MCP Mathematics • • • • • • • • • Conventional (Spunky Donkey) / Study Time Math • • • • • • • • • • Liberty Mathematics • • • • • Miquon Math • • • • • Math Mammoth (Light Blue series) * • • • • • • • • • Ray's Arithmetic • • • • • • • • • • Ray's for Today • • • • • • • Rod & Staff Mathematics • • • • • • • • • • Jump Math • • • • • • • • • • ThemeVille Math • • • • • • • Beast Academy (from -

Scenes for Teens

Actor’s choice: scenes for teens edited by JAson PizzArello Copyright © 2010 Playscripts, Inc. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying of this book or excerpts from this book is strictly forbidden by law. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form, by any means now known or yet to be invented, including photocopying or scanning, without prior permission from the publisher. Actor’s Choice: Scenes for Teens is published by Playscripts, Inc., 450 Seventh Avenue, Suite 809, New York, New York, 10123, www.playscripts.com Cover design by Michael Minichiello Text design and layout by Kimberly Lew First Edition: September 2010 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CAUTION: These scenes are intended for audition and classroom use; permission is not required for those purposes only. The plays represented in this book (the “Plays”) are fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations, whether through bilateral or multilateral treaties or otherwise, and including, but not limited to, all countries covered by the Berne Convention, the Pan-American Copyright Convention and the Universal Copyright Convention. All rights, including, without limitation, professional and amateur stage rights; motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording rights; rights to all other forms of mechanical or electronic reproduction not known or yet to be invented, such as CD-ROM, CD-I, DVD, information storage and retrieval systems and photocopying; and the rights of translation into non-English languages, are strictly reserved. -

Sunday Morning Grid 12/17/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/17/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Cincinnati Bengals at Minnesota Vikings. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Olympic Trials Golf PNC Father/Son 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Paid Program Nature Game Day 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Herd for the Holidays (N) 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Martha Jazzy Julia Child Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ KCET Special Å KCET Special Å KCET Special Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch A Christmas Kiss ››› (2011) Elisabeth Röhm. A Christmas Mystery (2014) Esmé Bianco. 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La fuerza de creer La fuerza de creer República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K.